A report from a United Nations body on environmental threats to Canada’s largest national park shows the urgency of the problems, says a spokesman for the First Nation that originally brought concerns about Wood Buffalo National Park to UNESCO.

The document, released last week and the latest in series of examinations of the park on the Alberta-Northwest Territories boundary, reaffirms threats from dams, oilsands development and climate change.

Melody Lepine of the Mikisew Cree First Nation says the report is clearer than ever about what needs to be done, and when, to keep the park in good environmental health.

“I think the experts recognized the sense of urgency is now,” she said Wednesday.

The Mikisew Cree brought concerns about Wood Buffalo, a World Heritage site, before UNESCO almost a decade ago.

The park’s traditional users saw water levels in the park dropping year after year because, they felt,of British Columbia’s upstream Bennett Dam. They also feared growing oilsands tailing ponds posed a risk to water quality.

UNESCO responded to those concerns in 2016, when an investigation found those fears well grounded. Ottawa developed an $87-million plan to better manage and monitor water in the park.

The new report is an assessment of how well that plan is working. It concludes there’s no need to remove the park’s World Heritage status at this time and praises many of the plan’s initiatives, such as the creation of wildland buffer zones.

But of 14 objectives for the park, UNESCO says only two are improving, with five stable and seven deteriorating. Five of its 17 recommendations pertain to the oilsands, including a call for a risk assessment of tailings ponds, reform to environmental monitoring, plans to reclaim the ponds that don’t threaten the park and reviewing new projects in light of what’s already been developed.

Although most of its recommendations have been made before, the new report suggests timelines. The risk assessment should be done by the end of next year; tailings reclamation plans should be complete before 2026; and land use plans should be “expedited.”

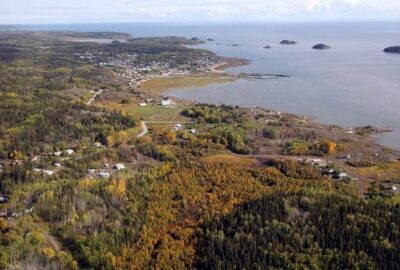

Lepine said those deadlines are the result of a visit the UNESCO team made to Fort Chipewyan, a community on the park’s boundary.

“They heard that urgency when they visited Fort Chipewyan. We are so worried.”

Lepine said concerns are even stronger after releases of oilsands wastewater from Imperial Oil’s Kearl site 70 kilometres north of Fort McMurray.

“The Kearl incident really shed light on the importance of managing the tailings ponds, getting them cleaned up.”

Gillian Chow-Fraser of the Canadian Parks and Wilderness Society agreed the new report is tougher.

“It’s much more robust in its drilling into oilsands management, really calling for much more specific and larger actions to improve tailings management.”

Kendall Dilling of Pathways Alliance, a group of all major oilsands producers, said its members “treasure Wood Buffalo National Park and the rich variety of life it supports.”

In a statement, Dilling said industry efforts to manage its environmental footprint are unprecedented and pointed out the wildland buffer around the park was achieved after oilsands companies surrendered leases in the area.

“We will continue to build on a decades-long track record of meaningful engagement with Indigenous groups on all aspects of our operations and environmental performance.”

He did not respond to specific questions on risk assessment, monitoring or tailings management.

Alberta Environment and Parks spokesman Benji Smith said the province is reviewing the report as it works toward reclaiming the oilsands. He said no tailings will be released without rigorous study.

“Work is underway to determine if, and how, oilsands mine water could safely be released at some point in the future,” he said in an email.

“Oilsands mine waters will not be approved for release until we can definitively demonstrate … that it can be done safely and that strict regulatory processes are in place to ensure the protection of human and ecological health.”

Parks Canada released a statement welcoming the UNESCO report.

“The report acknowledges that important progress has been made in the implementation of the action plan,” it said. “The government of Canada has been working in close collaboration with partners to advance research, ecological monitoring and ecological restoration projects throughout the park.”

It did not respond to any of the report’s recommendations, which include a call for further funding to improve water levels. Ottawa’s funding program for Wood Buffalo ends this year.

Lepine said even though many of UNESCO’s recommendations have been ignored, it has still been worthwhile to involve the group.

Some progress has been made, she said. And the threats to Wood Buffalo are now being taken seriously.

“We really showed the world, we showed Canada, that our concerns were real and substantive.”

This report by The Canadian Press was first published July 5, 2023.

Bob Weber, The Canadian Press

Share This: