Sign up for daily news updates from CleanTechnica on email. Or follow us on Google News!

This morning I had an excellent conversation with a lawyer with a maritime environmental non-governmental organization, Stephanie Hewson at the West Coast Environmental Law Association. She is preparing to testify to one of the highest legislative bodies in the country that they are based in, Canada’s Senate, regarding concerns about ocean geoengineering.

Canada’s Senate, the upper house of Parliament, is composed of 105 members who are appointed by the Governor General on the advice of the Prime Minister. Senators are selected to represent Canada’s provinces and territories, with the goal of ensuring regional balance in legislative decision-making. The Senate’s primary purpose is to act as a chamber of sober second thought, providing thorough review and debate of legislation passed by the elected House of Commons. This role aims to enhance the quality and fairness of laws while safeguarding regional and minority interests.

The Standing Senate Committee on Fisheries and Oceans is a Canadian Senate committee tasked with studying matters related to fisheries, oceans, and their associated policies and industries. Its mandate encompasses a broad range of topics, allowing the committee to investigate legislative and policy issues tied to Canada’s coastal and maritime sectors.

The Committee has been examining oceanic geoengineering, specifically ocean carbon sequestration, as part of its broader mandate to study matters related to Canada’s fisheries and oceans. This initiative was prompted by growing concerns over climate change and the potential role of ocean-based carbon sequestration techniques in mitigating its effects. The committee aims to assess the scientific, environmental, and regulatory implications of such geoengineering methods to inform potential policy and legislative actions.

On October 31, 2024, the Committee convened to explore the potential of ocean carbon sequestration as a tool for combating climate change. Expert testimonies were provided by Dr. Christopher Algar, Associate Professor of Oceanography at Dalhousie University, and Dr. Carly Buchwald, Canada Research Chair in Ocean Chemistry at the same institution. Joining them were Mr. Edmund Halfyard, Co-Founder and CTO of CarbonRun, and Dr. David Koweek, Chief Scientist at Ocean Visions. The panel discussed the scientific, technological, and environmental dimensions of using oceans to capture and store carbon dioxide, offering valuable insights to guide Canada’s approach to marine-based climate solutions.

The researchers from Dalhousie are working with ocean geoengineering startup Planetary Technologies to provide independent analysis and developing methods for modeling, monitoring, reporting, and verifying the outcomes of ocean alkalinity enhancement. As a reminder, I’ve looked at Planetary’s existing milk of magnesia approach and its claimed pivot to mine tailings electrochemical separation and find both to be without climate or economic merit.

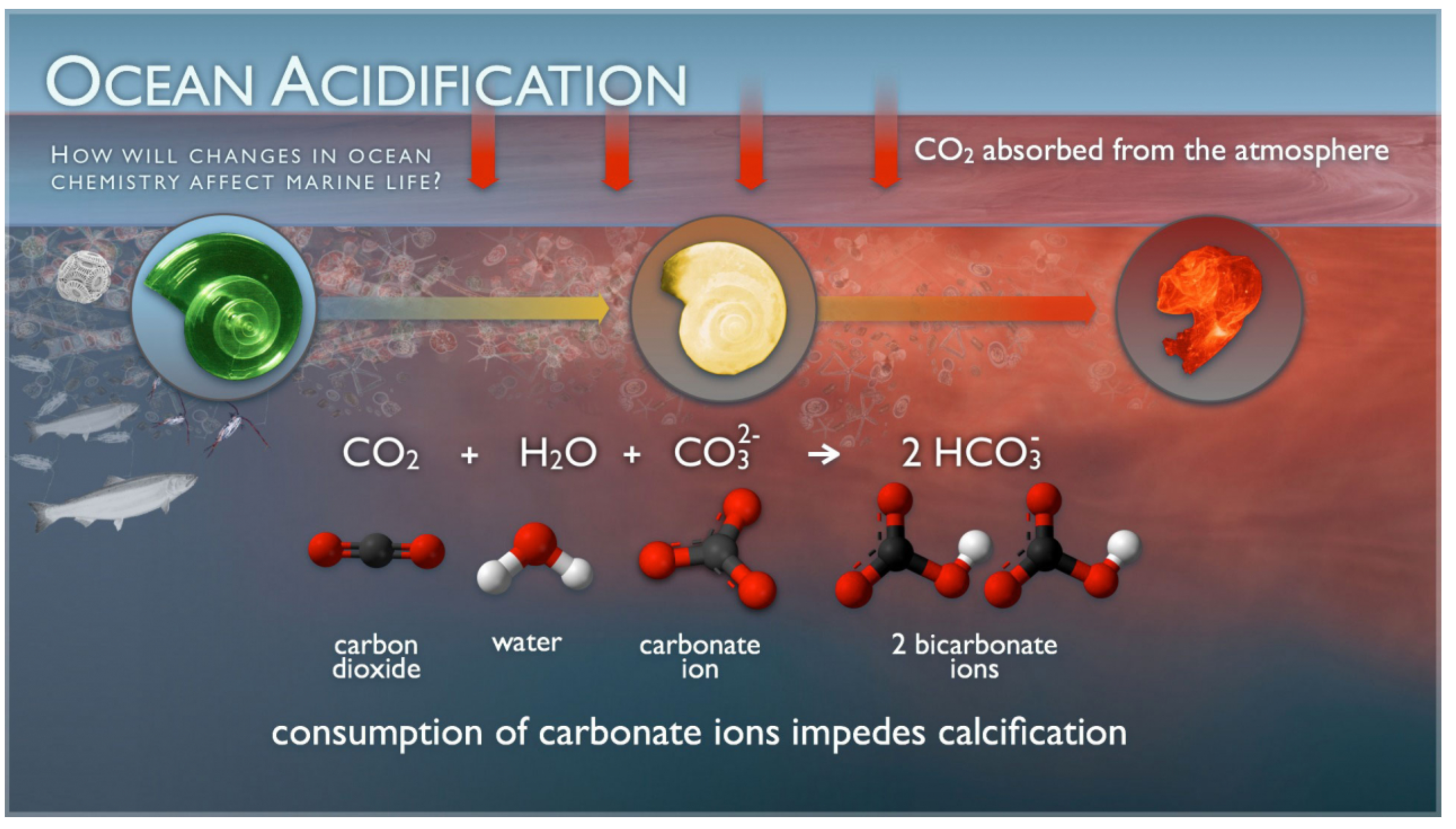

Halfyard, co-founder and CTO of CarbonRun, is leveraging his expertise in freshwater ecology to attempt to combat climate change. CarbonRun, a Nova Scotia-based startup, specializes in adding crushed limestone to acidified rivers, a process that restores ecosystems while sequestering carbon as stable bicarbonate. The company has received funding through initiatives such as Canada’s Net Zero Atlantic to explore nature-based carbon removal solutions, partnering with Nova Scotia Power, Dalhousie University, and local Indigenous communities. I haven’t published on this approach yet, but have heard of it. My initial sniff test suggests that while it has the co-benefit of de-acidifying rivers, it does so at the loss of carbonate ions necessary for shellfish formation that start in river water and end up in the sea, so has to be considered carefully.

Koweek, Chief Scientist at nonprofit Ocean Visions, is advancing strategies to combat climate change through ocean-based solutions. With a Ph.D. in Earth System Science from Stanford University and extensive research experience in coral reefs, kelp forests, and polar oceans, Dr. Koweek oversees initiatives focused on marine carbon dioxide removal. A seasoned field researcher and published scientist, he has participated in global expeditions and contributed to prestigious journals like Nature. Under his guidance, Ocean Visions continues to drive actionable solutions for improving ocean health and addressing climate challenges.

Is he a cautious guide? Here’s part of the transcript from his introductory remarks.

“Among the collective set of carbon dioxide removal options being considered, ocean-based pathways stand out for their scalable potential, yet they have not received research and development resources proportionate to their potential. Although there is an uptick in research and development of marine carbon dioxide removal pathways, much more must be done. My organization, Ocean Visions, has laid out an ambitious framework of integrated science, policy and technology development to be accomplished this decade to yield actionable information on which, if any, of the marine carbon dioxide removal approaches are sufficiently effective solutions and also safe for scaling in the decades to follow.”

At least at the first session, that’s multiple ocean chemistry types, people involved in startups, and NGO heads focused on expanding ocean geoengineering, yet no biologists or skeptical observers of the field.

Why did I bring up biologists when the question is carbon sequestration? Because carbon dioxide, when absorbed into the ocean, mostly picks up another carbon atom from carbonate ions as it turns into biocarbonate ions. And shellfish require carbonate ions to form their shells. As I said to the lawyer this morning, this is very well understood and poorly communicated under the label “ocean acidification,” which leads most people to misunderstand the mechanism of harm involved. In fact, oceans simply become a little less alkaline, reducing their ability to absorb carbon dioxide, not acidic. Alkaline substances can be just as corrosive as acids, but that’s not what’s harming shellfish.

On November 7, 2024, the Standing Senate Committee on Fisheries and Oceans continued its examination of ocean carbon sequestration, hearing from two leading experts. Dr. Anya Waite, CEO and Scientific Director of the Ocean Frontier Institute, and Dr. Galen McKinley, Professor of Earth and Environmental Sciences at Columbia University, provided testimony on the opportunities and risks of employing ocean-based strategies to combat climate change. The discussions highlighted the scientific, logistical, and regulatory challenges of implementing such solutions in Canada, offering valuable insights to inform future policy decisions.

Waite is a biological oceanographer and CEO of the Ocean Frontier Institute, and has engaged in research related to ocean geoengineering, notably participating in the first Southern Ocean Iron Fertilization Experiment (SOIREE). The Institute has a research goal of ocean carbon sequestration, so more advocates rather than skeptics. But Waite is at least a biologist. However, per the transcript, Waite never mentioned carbonate ions or shellfish in any way. It seems shellfish shell formation isn’t among her research interests, which have focused on nitrogen and particle dynamics in mesoscale eddies. This is not a slight, as specialization is required, and the topics Waites addresses are very important, but as the sole biologist speaking with the Senate committee, it’s a problem for the process.

McKinley is a professor at Columbia University’s Lamont-Doherty Earth Observatory advancing research into the ocean’s capacity to absorb carbon dioxide and its implications for combating climate change. With a Ph.D. in Climate Physics and Chemistry from MIT, McKinley uses sophisticated climate models and data science to study the physical and chemical processes that make the ocean a critical carbon sink, sequestering 25% of global CO₂ emissions annually.

On November 21, 2024, Committee continued its study of ocean carbon sequestration. Testifying were Mike Kelland, CEO of Planetary Technologies, and Dr. William Burt, Chief Ocean Scientist at Planetary Technologies and adjunct professor at Dalhousie University. Also that day, the Committee heard testimony from Kimberly Gilbert, Co-Founder and CEO of pHathom Technologies, and Shannon Sterling, Founder of CarbonRun and Associate Professor at Dalhousie University.

I’ve already referenced Planetary Technologies, but perhaps a bit more is worth noting. It’s a startup that’s received a lot of governmental and startup funding, including a Musk-funded Carbon Removal X Prize. It was founded with the intent to commercialize adding magnesium hydroxide — commonly known as milk of magnesia, an antacid — into seawater to increase alkalinity and hence the uptake of carbon dioxide from the atmosphere. It took about 25 minutes one morning to figure out that the costs were prohibitive and that no net carbon drawdown would occur given the carbon debt of magnesium hydroxide.

Kelland is the CEO of the Nova Scotia-based company focused on ocean-based carbon dioxide removal using ocean alkalinity enhancement. He holds a degree in mechanical engineering and has a background in leading technology and software startups.

Burt has a Ph.D. in Chemical Oceanography from Dalhousie University and a background in marine chemistry research at institutions like the University of Alaska Fairbanks. He focuses on ocean alkalinity enhancement to boost the ocean’s capacity to absorb atmospheric CO₂.

A comment thread with Kelland on LinkedIn made it clear that they had realized that despite magnesium hydroxide being all over their website and the basis of their two pilot sites, they had realized it wouldn’t possibly cut it from a cost and carbon perspective. Kelland asserted that they were pivoting to electrochemical separation of alkaline materials and high value metals from mining tailings. My assessment is that if they could do it for the price point they were targeting that they and the climate would be far better off selling the resulting minerals and chemicals to displace high-carbon chemicals from the market, reaping much more money and better climate results. Given that they have joined a long, long list of companies claiming to separate valuable materials from mining waste with electrochemistry and I’m unaware of any that have been successful economically, I think this is going to be just as much a failure as magnesium hydroxide.

Sterling is an Associate Professor in the Department of Earth and Environmental Sciences at Dalhousie University. She earned her Bachelor of Science in Geography from McGill University, a Master of Science in Fluvial Geomorphology from the University of British Columbia, and a Ph.D. in Earth Sciences from Duke University. Her research focuses on hydrology and biogeochemistry, with an emphasis on freshwater acidification and climate change. Dr. Sterling is also the founder of CarbonRun, a company dedicated to innovative river restoration techniques aimed at enhancing carbon sequestration.

Gilbert is the Co-Founder and Chief Executive Officer of pHathom Technologies, which has developed a method to capture CO₂ emissions from power plants and use the ocean’s natural carbon cycle for long-term storage. In June 2024, pHathom Technologies was awarded a $50,000 equity investment from the New Brunswick Innovation Foundation during the Atlantic Venture Forum’s Female Founders’ Startup Showcase, marking the second investment from NBIF to support the company’s pilot projects and technological advancements.

As far as I can tell from the transcripts, Gilbert is the only person to mention carbonates and their importance to shellfish, with Burt adding testimony which makes it clear that he doesn’t understand the mechanism of concern, instead talking about corrosivity, and Kelland talking about nutrients in this session.

So far, the people appearing before the Committee are much more in the camp of advocates, not skeptics, and a skeptical and informed eye is required on this space. I’ve been looking at it on and off for years, with a series of assessments of different proposed solutions published over the past year, not only on Planetary, but also a California startup that wants to separate carbon dioxide from seawater, another California startup that wants to add carbon dioxide to seawater, an Italian startup that wants to make most of cement in a low-carbon way but instead of using it as low-carbon cement put it in the ocean, and a group that wants to turn the world’s beaches green. This on top of my work assessing all million ton plus carbon capture and sequestration sites globally and finding that the money would have gone a lot further building wind and solar, and my work assessing direct air capture solutions whose only natural market is enhanced oil recovery.

On December 12, 2024, the Committee will continue its study on ocean carbon sequestration and its potential applications in Canada. Witnesses include Tom Heintzman, Managing Director and Vice-Chair of Energy Transition and Sustainability at CIBC Capital Markets, who will provide insights on the economic and policy frameworks for carbon solutions; Stephanie Hewson, Staff Lawyer at West Coast Environmental Law Association, offering perspectives on environmental governance and legal considerations; and Paul Snelgrove, Research Professor at Memorial University, who will share expertise on marine ecosystems and the science underpinning carbon sequestration technologies. The session aims to advance the committee’s understanding of both the scientific and socio-economic implications of these strategies.

Heintzman is irrelevant to the technical and biological discussion, being a founder of a green energy company and holder of a law degree. No flies on him, but the odds of him understanding the biology and chemistry or contributing value on concerns are low. He has discussed nature-based carbon drawdown and carbon credits related to them, which is to say the voluntary carbon market which has proven so problematic.

Snelgrove is a Research Professor in the Department of Ocean Sciences and Biology at Memorial University of Newfoundland and an expert on marine biodiversity and ecosystem function. With a Ph.D. from the MIT-Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution Joint Program, Snelgrove’s work explores the impacts of human activities on ocean environments, contributing to conservation strategies and sustainable management. With luck he’ll be providing more coherent concerns related to ocean geoengineering. Unlike so many others who have been testifying, he doesn’t appear to have made an academic or professional career in the field, which lends hope that caution will be the basis of his perspective.

Hewson is of course the lawyer with the non-governmental maritime ecosystem protection group I spoke with today. She reached out to me based on the articles I’ve published on the subject over the past year. As we agreed, there isn’t a lot of accessible publication on the subject. I’ve spent years getting a sufficient understanding to not be too wrong too often about oceanic chemistry and biology, and much of that was gained by looking at ocean geongineering schemes and asking obvious questions.

One fascinating thing that came out of our conversation was that ocean geoengineering schemes such as every one that I’ve looked at aren’t covered by any maritime protection international treaties or agreements. The London Protocol, an international treaty under the International Maritime Organization, a UN agency, aims to protect the marine environment from pollution caused by the dumping of waste at sea. In 2013, an amendment was adopted to regulate ocean geoengineering activities, recognizing their potential environmental impacts. The amendment prohibits ocean fertilization and other geoengineering activities unless they are scientifically assessed and authorized as legitimate climate mitigation measures. This precautionary approach ensures that such activities do not harm marine ecosystems while advancing global efforts to address climate change.

However, that’s only activities that don’t use land-based facilities, which is to say all the ones I’ve explored above. It makes incredible economic sense to base facilities on land because building at sea is much more expensive, and constant flow efforts like desalination are much more efficient than batch processes involving ships carrying loads of something out to sea. This reflects the apparent origins of the amendment in ocean fertilization, which barely gets a mention these days by comparison to the various chemical and electrochemical processes such as Planetary’s that I’ve assessed.

Those should be covered by the UNEP’s Global Programme of Action for the Protection of the Marine Environment from Land-Based Activities, established in 1995. The program focuses on reducing pollution from sources such as agricultural runoff, wastewater, and industrial discharge, which threaten marine ecosystems and coastal communities, but it makes no mention and I can find no reference to it intending to deal with land-based ocean geoengineering schemes.

In other words, if any of these startups built ships to do what they intend to do, the dubious wait of the London Protocol would weigh upon their shoulders, but as it is, they don’t discharge anything considered a pollutant so are getting a free ride. Perhaps that’s why so few of them have biologists on staff.

Chip in a few dollars a month to help support independent cleantech coverage that helps to accelerate the cleantech revolution!

Have a tip for CleanTechnica? Want to advertise? Want to suggest a guest for our CleanTech Talk podcast? Contact us here.

Sign up for our daily newsletter for 15 new cleantech stories a day. Or sign up for our weekly one if daily is too frequent.

CleanTechnica uses affiliate links. See our policy here.

CleanTechnica’s Comment Policy