Last Updated on: 23rd June 2025, 10:39 am

The June 2025 U.S. bombing of Iran’s nuclear facilities is shaping up to be a pivotal geopolitical event, one whose immediate shockwaves extend far beyond military calculations. Within hours of the U.S. and Israeli strikes on key nuclear sites at Natanz, Isfahan, and Fordow, global oil prices surged sharply. President Trump’s provocative declaration that “Fordow is gone” and his blunt demands for Iran to accept peace quickly have dramatically heightened uncertainty in energy markets, underscoring once again the acute vulnerabilities that accompany reliance on petroleum.

History has repeatedly shown how disruptions centered on the Persian Gulf, whether from political upheaval, sabotage, or outright warfare, instantly sends crude oil prices higher. This pattern is repeating itself, intensifying pressures on consumer nations around the globe.

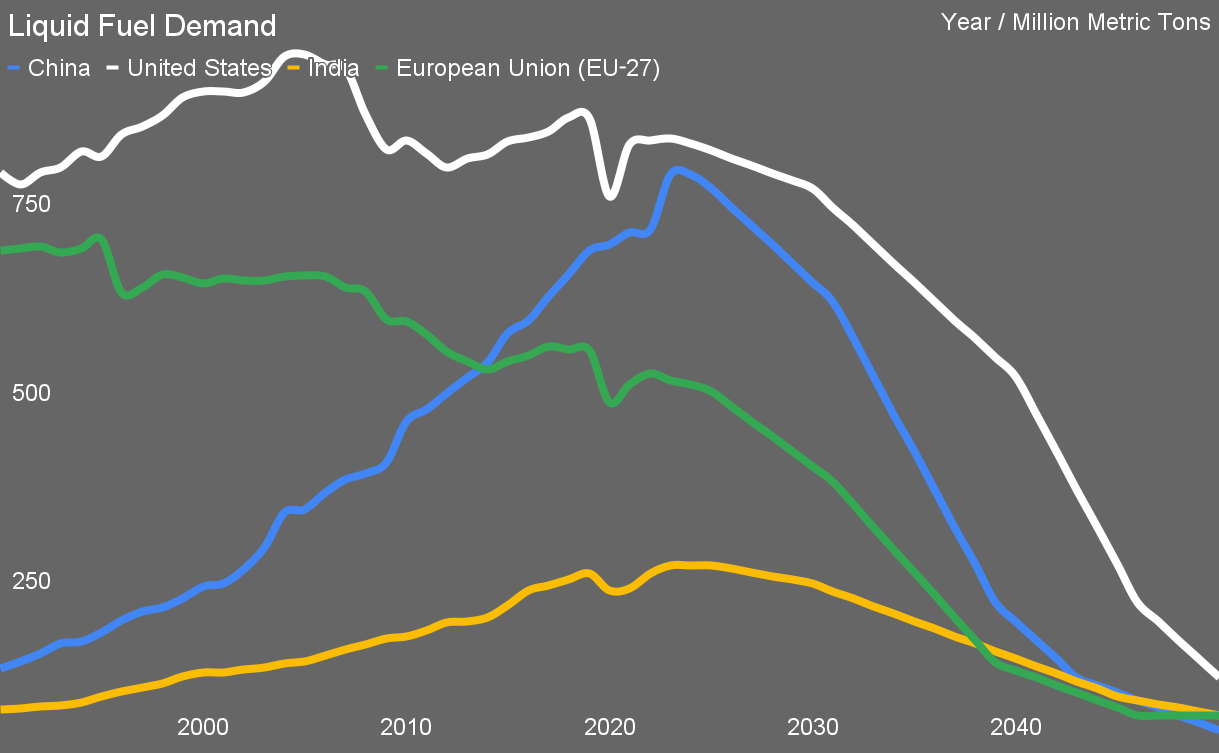

I assembled this necessarily coarse perspective this morning, first finding data sources sufficient to get at least approximate numbers of metric tons of petroleum-based fuels consumed in the four countries/regions, then assessing the near-term implications through 2030, then extending that through 2050 with policy and competition-based drivers of transformation. Errors in data gathering, conversion, and transcription from 1990 to the present are mine, while errors in projection are also mine, but differently. As always, with my projections in the future, I don’t claim to be right, just less wrong than most.

The sharp oil price spike following Trump’s strikes has immediately pushed inflation fears back into the spotlight. Already fragile economies, including the United States, are facing renewed recessionary pressures, dubbed by many analysts as the Trumpcession. American consumers, uniquely sensitive to fuel costs due to the comparatively massive distances they drive and fly, and the lack of alternatives, now see gasoline prices soaring at the pump, directly squeezing disposable incomes. This immediate hit to household spending could further stall the U.S. economy, a dynamic that, paradoxically, is likely to boost consumer interest in electric vehicles and other less oil-dependent transport options, despite the absence of robust federal policy to promote such technologies.

In contrast to the reactive, consumer-driven scenario playing out in the U.S., China is responding to the crisis with clear-eyed strategic intent. Already leading global markets in electric vehicle production, battery manufacturing, and renewable energy deployment, China is now likely to double down on its transition. Beijing has long understood energy security as synonymous with national security, and with its oil imports critically exposed to geopolitical disruptions, the government will aggressively accelerate its electrification agenda. Policy initiatives such as stringent EV quotas, massive investment in battery factories, and widespread deployment of charging infrastructure all appear prescient as China seeks to further insulate itself from the volatility now gripping oil markets.

All countries are exposed to increasing volatility as demand drops, as major oil-producing regions will become uneconomic, major fields and refineries go off line, bulk shipping transitions to aging and less reliable ships, and major pipeline infrastructure becomes stranded assets. The illegal US strikes on Iran — illegal under both US and international law, but as always with the USA, never coming with consequences — are just sharpening the awareness of the volatility.

Ironically, the global decline in oil demand will accelerate itself, as recurring price spikes and supply chain disruptions caused by economic instability make oil even less attractive.

The European Union, similarly positioned on the frontline of petroleum dependency, will take this geopolitical crisis as further justification for its ambitious electrification and renewable energy programs. Europe’s accelerated pivot away from Russian fossil fuels in response to the 2022 invasion of Ukraine already set a strong precedent. That policy momentum will now be amplified by fears of another sustained price spike driven by Middle Eastern conflict.

The EU’s Fit for 55 plan, its rapid expansion of charging infrastructure, and its steadfast implementation of carbon pricing mechanisms collectively position Europe to decisively reduce petroleum dependency. Policymakers across the continent clearly see electrification as the best hedge against geopolitical volatility and as a cornerstone of broader decarbonization and energy security strategies.

This doesn’t bode well for some aspects of the Netherlands, where I’m typing this prior to the start of a week of workshops with TenneT. At present, 4% of their GDP is tied up in energy and petrochemicals, with the large majority being for fossil fuels. That’s broken down as 3% fossil fuels, 0.4% petrochemicals, 0.5% transmission, and 0.05% biofuels. The country imports crude and exports petroleum products, mostly fuel for ground, water, and air transportation. The country refines the majority of shipping and aviation fuels for Europe, some 70 million of 90 million tons of demand. While longer haul shipping and aviation will continue to need liquid fuels, the volumes won’t be nearly as large as present. (These numbers are approximate and from public sources over the last few years, assembled quickly to give me a sense of scale, so where they are obviously out, the error is with me.)

I expect the roughly 120 million metric tons of liquid fuels the country exports, including bunkering for cross-border aviation and ships, will plummet to 20 million tons. The current 2.5 million tons of biofuels will expand supply. That won’t satisfy European’s demand, but biofuels will be made from European waste biomass where the biomass is — biomass won’t be shipped to the refineries of the Netherlands in my opinion.

India, meanwhile, faces a particularly stark choice. Its petroleum demand has been growing rapidly, placing significant strain on the country’s import-dependent energy economy. Note that despite having 1.4 billion citizens and being the most populous country in the world, having just overtaken China, and having a GDP that’s fifth in the world and purchasing power parity that’s third in the world, its consumption of petroleum fuels for transportation is the lowest among the four major economies under consideration. It’s still consuming a quarter of a billion tons of oil-based fuels a year.

The current crisis underscores the acute risks this dependency poses, likely prompting Indian authorities to seize the moment to accelerate their electrification efforts. With ambitious targets for electric vehicle adoption, large-scale renewables deployment, and incentives aimed at building domestic battery production capacity, India is signaling a strategic pivot. Although still at an earlier stage of transition compared to China or Europe, India’s momentum will visibly intensify in response to this latest geopolitical shock, underscoring the importance of secure, domestically-controlled energy infrastructure.

While the U.S. market reaction is dominated by short-term consumer pain rather than coordinated policy, this crisis underscores an important insight I presented on the Redefining Energy podcast earlier this year. My prediction was that 2025 would mark a decline in U.S. oil production, driven by factors such as the financial discipline imposed by investors, maturing shale assets, and limited appetite among drillers to ramp up production again quickly.

Many industry observers incorrectly assume that price spikes automatically trigger substantial new shale investment and production. However, today’s volatile environment and the profound financial uncertainty of another boom-bust cycle mean that this traditional response is no longer likely. Producers learned harsh lessons during the shale boom-and-bust of the last decade. Investors are now unwilling to bankroll new shale developments solely in response to short-term price volatility. Consequently, even this latest dramatic increase in oil prices is unlikely to lead to a meaningful resurgence in U.S. shale oil production.

Looking ahead, global liquid fuel demand is set for significant transformation. By mid-century, it is clear that electrification will dominate ground transportation markets in China, Europe, and India, with the U.S. somewhat slower but inevitably following suit. Passenger cars, buses, and trucks will become predominantly electric, driven not just by climate policies but also by national energy security strategies. Rail will all electrify, with India approaching 100% today and the U.S.A. lagging badly at present. Similarly, short-haul aviation and coastal shipping are on trajectories to embrace electrification technologies, including battery-electric and hybrid solutions. The technology required to electrify shorter routes is rapidly maturing and will be economically and strategically compelling by 2035.

However, long-haul aviation and maritime shipping face more challenging energy requirements and will largely transition to sustainable liquid biofuels. Advanced biofuel technologies, particularly sustainable aviation fuels and marine biofuels, are likely to become dominant, supported by policy frameworks that prioritize secure, low-carbon energy sources. Biofuels supplied by domestic waste biomass feedstocks — notably sewage, animal dung, food waste — are also a form of energy security, with citizens and food production for them being the source. By 2050, traditional petroleum fuels are projected to occupy a significantly diminished share of the global energy landscape, largely relegated to niche applications or regions slower in their transitions. That doesn’t apply to petrochemicals. The end of the age of oil for energy isn’t the end of the age of oil for useful molecules, we just won’t be burning them, and the volumes will be vastly smaller.

This unfolding scenario presents clear implications for policymakers and investors. Governments in China, Europe, and India are rapidly aligning their energy policies toward electrification and renewable power already, and will accelerate this, providing clarity and certainty for investors. Capital will increasingly shift away from petroleum infrastructure, including refining and pipelines, toward electricity grids, battery manufacturing, EV production, renewable power generation, and biofuel processing facilities. Conversely, investors exposed heavily to long-term petroleum infrastructure risk significant asset stranding, particularly as major markets shrink their reliance on liquid fuels in response to repeated geopolitical shocks.

In essence, Trump’s bombing of Iran’s nuclear infrastructure has crystallized a fundamental reality: energy systems dependent on oil are inherently vulnerable unless a country is a petrostate. That’s true for all but one of these major economic blocs, the United States, with China leading globally in the rush to become an electrostate. Countries recognizing this vulnerability are already moving swiftly to reduce their exposure. This acceleration in electrification and renewable energy investment is not merely about responding to climate change, it is about ensuring national security, economic stability, and resilience against future geopolitical upheavals.

Sign up for CleanTechnica’s Weekly Substack for Zach and Scott’s in-depth analyses and high level summaries, sign up for our daily newsletter, and follow us on Google News!

Whether you have solar power or not, please complete our latest solar power survey.

Have a tip for CleanTechnica? Want to advertise? Want to suggest a guest for our CleanTech Talk podcast? Contact us here.

Sign up for our daily newsletter for 15 new cleantech stories a day. Or sign up for our weekly one on top stories of the week if daily is too frequent.

CleanTechnica uses affiliate links. See our policy here.

CleanTechnica’s Comment Policy