For Canada’s producers, the government-owned project offers a chance to break their almost total dependence on exports to the US and win higher prices for their crude. For global markets, the Trans Mountain expansion represents a new source of the heavy, sludgy oil that advanced refineries in India and China crave for producing transportation fuels and asphalt.

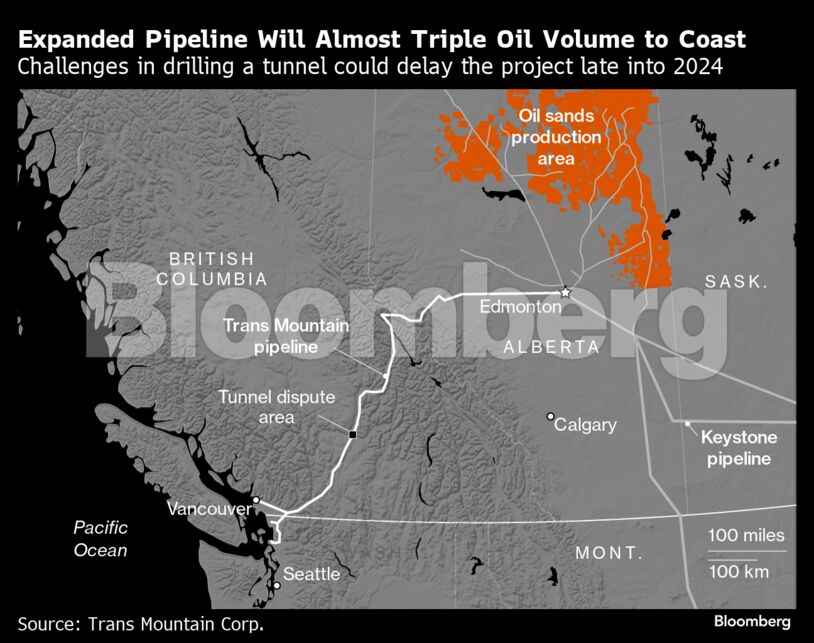

The project — which essentially twins an existing 1950s-era pipeline — had been expected to start operating the first quarter of next year, but technical challenges in tunneling along a 1.3-kilometer (0.8-mile) stretch have forced the company to seek changes that could delay the startup. A postponement would be an unwelcome development for a project that already has been delayed for years — and seen its costs balloon — because of opposition from environmentalists and indigenous groups.

Here’s a look at the mega pipeline as the in-service date approaches, whenever that may be.

1. What is the Trans Mountain pipeline?

Trans Mountain is a 715-mile pipeline that runs through the Canadian Rockies’ vast swathes of pine trees on its route from landlocked Alberta to the west coast city of Vancouver. The original line, Canada’s only pipeline to the Pacific, is 70 years old and supplies oil mainly to refineries in British Columbia and Washington State. Twinning the line will boost capacity to 890,000 barrels a day from about 300,000 barrels currently.

The project faced multiple setbacks in the seven years since it was first approved amid opposition from environmental groups concerned about the effect of increased ship traffic on killer whales and indigenous communities that worry that the line could sully their land.

In 2018, original owner Kinder Morgan Inc. threatened to cancel the expansion, prompting Prime Minister Justin Trudeau to buy the system for C$4.5 billion ($3.3 billion) to save it from the scrap heap. Since then, floods, worker shortages and fatalities, as well as the Covid-19 pandemic, have caused the project’s cost to quadruple to almost C$31 billion and delayed the startup by about two years.

2. Where will the oil go?

It remains to be seen whether Trans Mountain will fulfill its goal of breaking Canada’s dependence on US buyers for its oil.

While the expansion was intended to bring Canadian crude to Asia, some traders and analysts say the natural destination for the crude are the dozen refineries along the US Pacific Coast owned by the likes of Chevron Corp., BP Plc and Marathon Petroleum Corp. Those facilities currently source much of their feedstock from Saudi Arabia or Iraq, which takes 30 days to arrive on the ocean, versus about four days of sailing from Vancouver, where Trans Mountain ends.

The US West Coast is “an easier fit for the majority of volumes early on,” said John Coleman, Wood Mackenzie Ltd.’s research director. In the near term, Canadian crude would have a tough time breaking into an Asian market that’s currently flooded with Russian oil, he said.

But even longer term, the oil terminal at Trans Mountain’s end can only handle ships carrying, at most, 600,000 barrels of oil. Trips to Asia are more economical in supertankers that hold three times that amount, he said.

Still, not everyone thinks the main destination will be the US.

“The majority of the oil will be going to Asia because California is not geared to process heavy Canadian oil,” says Martin King, a senior oil analyst with RBN Energy. Among the shippers on the line is Chinese trader PetroChina, which reserved enough space on Trans Mountain to fill a supertanker per month.

3. How else will Trans Mountain affect global oil flows?

If California refineries buy crude off Trans Mountain, they may buy less from places like Ecuador, Brazil and Guyana, forcing those barrels elsewhere on the US Gulf Coast, and in Asia and Europe.

It could also roil flows inside the US, reducing the volumes piped to the Midwest and Texas. Last year, Canada accounted for 100% of oil imported by Midwest refiners and a third of foreign oil used on the Gulf Coast, home of one of the world’s largest refining hubs.

Trans Mountain also could disrupt Montreal, which primarily gets light Canadian oil via pipelines that operate on a non-committed basis. If those volumes are rerouted via Trans Mountain, Montreal refiners may have to import more light oil from the US.

Flows of Alaska North Slope crude, which accounts for about half of the diet of California refineries, could also be upended. Alaska’s ice-free Valdez terminal doesn’t have the same size restrictions as Trans Mountain’s Vancouver port so Alaskan oil may start sailing to Asian markets while Canadian oil takes its place at California refineries.

4. Who will ship oil on Trans Mountain?

Ten companies, including BP Plc and PetroChina Co., have committed to ship about 710,000 barrels of oil a day on Trans Mountain, accounting for about 80% of its total capacity.

Since the contracts require companies to pay even if they don’t use the line, they may shift their oil away from pipelines without contracted space, including Enbridge Inc.’s Mainline system, which is Canada’s largest oil export pipeline network. Volumes on the Mainline, which supplies US Midwest refineries, may fall as much as 300,000 barrels a day once Trans Mountain is fully in service, according to RBC Capital Markets.

Companies contracted on Trans Mountain originally expected to pay fixed tolls of C$4.33 a barrel. Since then, fixed interim tolls have jumped to C$10.88 a barrel due to cost overruns on construction, undermining the project’s promise of providing a cheap route to Asian markets.

Still, the toll issue isn’t entirely settled as companies including Canadian Natural Resources Ltd. are pushing regulators to evaluate the fees.

With tolls so high, the line may fail to attract uncommitted shippers, who typically pay even more than contracted shippers. Traders estimate that less than 70% of the new capacity will be effectively used, meaning that the line may end up adding no more than 440,000 of new barrels daily.

5. What does Trans Mountain mean for Canadian crude production?

Canada’s oil producers, concentrated in the remote oil sands of northern Alberta, have suffered from a dearth of export pipelines, restricting their ability to grow.

Trans Mountain is poised to create more capacity than the industry needs, at least for a few years, prompting companies including Canadian Natural and Cenovus Energy Inc. to plan to boost output. Canada’s oil production may rise by more than 900,000 barrels a day to more than 6 million barrels a day by the end of the decade, according to the Canada Energy Regulator.

“It will have a significant impact on the short term and long term,” Alberta Minister of Energy and Minerals Brian Jean said in an interview at a BloombergNEF event in Calgary on Tuesday. “And I believe that we need to continue to look at opportunities to distribute our products to the world.”

6. What does Trans Mountain mean for oil prices?

The heavy discounts Canadian oil has to endure are expected to shrink when Trans Mountain starts service. Western Canadian oil currently sells at a discount of $17 a barrel to benchmark US crude. That discount could fall to the single-digits, according to traders.

The growing importance of Trans Mountain as an outlet for Canadian exports also could make the pipeline’s starting point at the Edmonton terminal in Alberta into a significant new pricing center for crude.

Share This:

Next Article