Developed-world governments continue to spend beyond their means, borrowing and printing money to pay for their exorbitant expenditures. None of it has any consequences, other than inflation, due to fiat currencies. It doesn’t matter how high interest rates go, they just keep borrowing, adding to deficits and national debts.

This is unsustainable and eventually will come to a crashing halt. When an individual borrows money he/she starts a loan by paying mostly the interest off first. Gradually the principal gets paid down and the loan is paid off.

The politicians in power are no different, except they don’t care about paying off their loans, they are content to just pay the interest. They issue Treasury bills to get people, corporations and other governments to buy their debt. They pay out interest to bondholders but how much of the principal is actually being paid down? Very little I would argue, if it were global debt levels would not continue to hit records year after year.

How long before interest payments are so high that governments can no longer afford them? That would mean a debt default.

Uninverted yield curve signaling recession — Richard Mills

In the US, Canada and Europe, governments keep kicking the debt can down the road. Interest rate reductions have already begun in the UK and Canada and they are soon to happen in the US. Are we zero bound? We all know what that means: a goosed stock market, more borrowing, more debt.

How many kicks of the can have we got left?

It turns out more than most of us think. I think the global government’s will get quite creative in finding new ways to continue out-of-control government spending, no matter which who, or which party is in office. Here we offer three possibilities.

But first, the state of the economy and why the United State is likely to avoid a recession.

Yield curve uninversion

In a typical healthy market, the yield curve (typically the spread between the US 10-year Treasury note and the 3-month or the 2-year note) shows lower returns on short-term investments and higher yields on long-term investments. This makes sense, as investors earn more interest for tying up their money for longer. The yield curve is said to “invert” when short-term yields are higher than long-term yields.

The yield curve has inverted 28 times since 1900, and in 22 of those times, a recession followed. For the last six recessions, a recession began six to 36 months after the curve inverted. Typically a recession follows six to 12 months after the yield curve inverts.

After US job openings fell to the lowest since the start of 2021, the yield on the 2-year Treasury note on Sept. 4 fell briefly below the 10-year note. It’s only the second time this has happened since 2022.

Prima facie, this seems like a good thing. Investors now have more confidence that the economic future is brighter and that locking in their money at higher rates is safe.

However, according to Motley Fool contributor James Brumley:

Except the uninversion of the long-inverted yield curve isn’t quite what it seems to be on the surface. The inversion has been undone mostly because the market’s now betting on more aggressive rate cuts than previously expected, suddenly dragging long-term interest rates much lower than shorter-term rates have fallen. And regardless of how it happens, the reversal of such an inversion doesn’t necessarily mean we’ve sidestepped trouble. The recessions often predicted by a yield curve’s inversion typically don’t start until after the inversion is unwound.

Back in December 2023, our article ‘Hard Landings Recession Predictions Wrong’ took aim at those who believe the Fed’s steeply rising interest rate hikes would cause a recession.

I was right in my prediction that the Fed would pause interest rate hikes in June 2023.

I’ve also voiced my opinion that we will get a soft landing with no, or an extremely shallow and very short recession. Remarkably, the Federal Reserve has raised interest rates fast enough to reverse the inflation rate, without causing a severe downturn. And it’s done it in a short amount of time.

I’m sticking with my prediction of a quarter-point cut in September and possibly another 25 basis-points reduction before the end of the year, with the rate easing cycle continuing well into the new year. I do not see a recession until late in in 2025.

While some economists are forecasting a 50-point cut in September, I think that would panic the market and is something the Fed would want to avoid.

Why this time might be different

Rather than rushing headlong into recessions, as have previously occurred every six to 36 months following a yield curve inversion, there are several reasons why it may not happen this time round.

The US Treasury yield curve officially exited its prolonged inversion on Friday, Sept. 6, marking the end of over two years when yields on short-term bonds were higher than those on long-term bonds.

The end of the inversion came in response to weaker-than-expected jobs data from the August nonfarm payrolls report. Coupled with other recent negative economic data, the Federal Reserve is poised to begin cutting interest rates this month.

“Fixed-income investors are increasingly aligning with our view that the U.S. economy won’t slip into a recession, especially now that the Fed seems committed to easing its policy to avert one,” said Ed Yardeni, a veteran Wall Street strategist and founder of Yardeni Research, via Bezinga.

Yardeni believes the yield curve could steepen significantly without a recession materializing. While the 2-year and the 10-year are currently similar, around 3.6%, in past cycles the spread between the two bonds peaked at an average of 220 basis points.

If the 2-year yield bottoms around 3.00% during this easing cycle, the 10-year yield could rise to 5.20%, significantly above its current level of 3.6%, according to Bezinga.

Yardeni believe the “neutral 2-year yield” (the “Goldilocks zone of neither too low nor too high) is around 3% and the neutral 10-year yield is about 4%.

With US inflation falling to 2.5% in August — close to the Fed’s 2% target — the bond market now expects the Fed to prioritize growth over inflation, betting on a softer economic landing than previously feared, states Bezinga, adding that the flattening and eventual steepening of the yield curve suggests a more stable economic outlook:

“The yield curve’s dispersion might not completely eliminate recession risk but for now markets appear to be betting on a more favorable outcome, a cooling economy without a hard crash.”

Global debt

At AOTH we keep a close eye on the dollar and bond yields because they have so much bearing on precious metals and other commodities. We aren’t worried about a recession but the amount of global debt and in particular household debt is concerning.

Visual Capitalist just published an infographic indicating that the global debt, all sectors, for the first quarter of 2024 reached $315.1 trillion. That’s nine times higher than the US national debt of $35 trillion. It rose for the second straight quarter to a new record high.

Mature markets accounted for $209.7T, about two-thirds of the total, while emerging markets represented $105.4T. Visual Capitalist notes that total global debt increased by 2.6% year on year, with the government sector showing the largest annual increase of 5.8%.

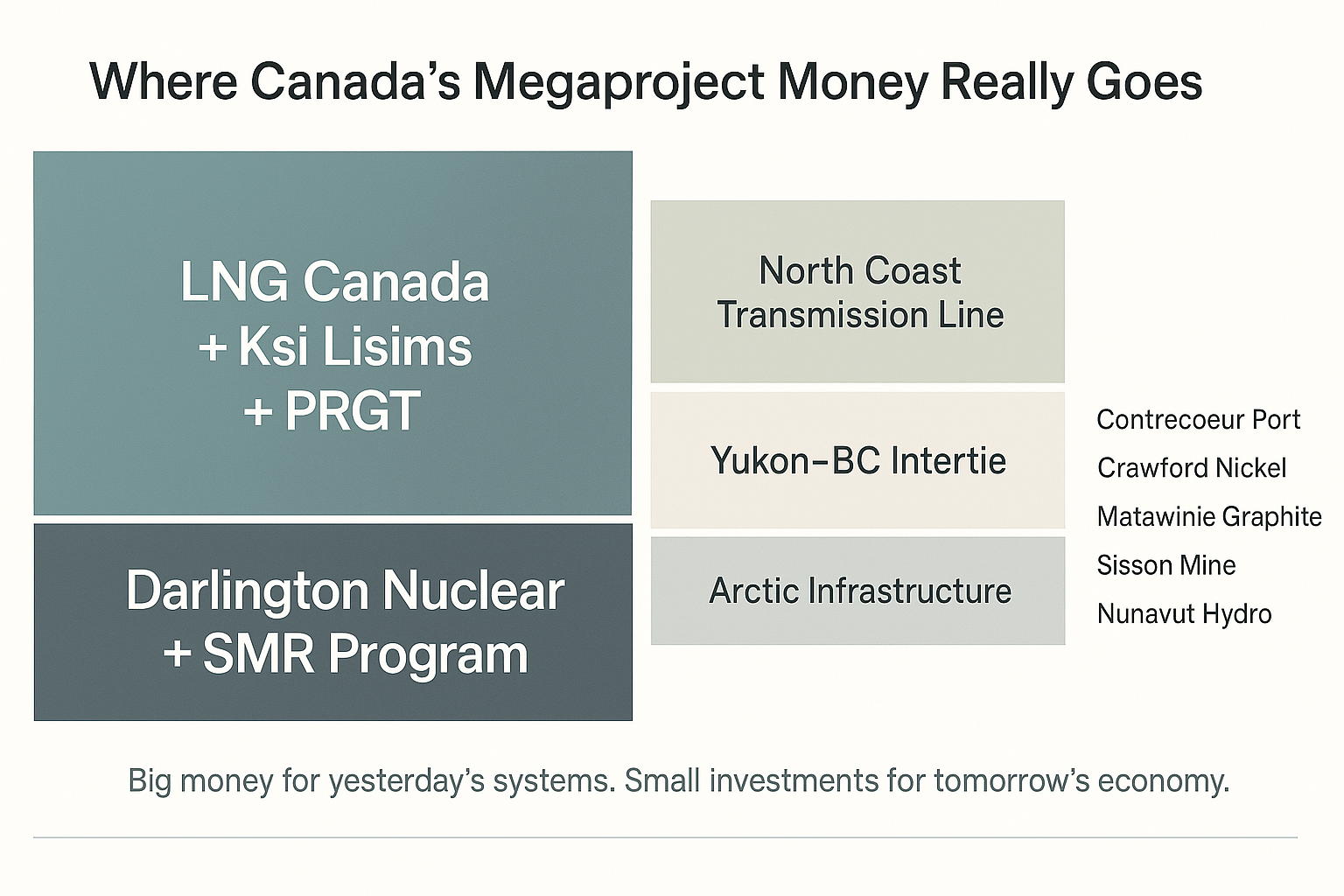

No surprise there. We recently reported that in Canada, government spending accounted for a whopping 80% of GDP growth in Q2.

The publication voiced concern over the amount of emerging market debt, which is more than double what it was a decade ago. Non-financial corporates represented the largest share of emerging market debt, suggesting that these countries are heavily leveraging corporate debt for growth and expansion. Corporate debt is riskier since there is always the possibility of a bankruptcy, ending the ability of the company to pay interest earned by its bondholders.

Source: Visual Capitalist

Household debt – ratio of household debt to disposable income

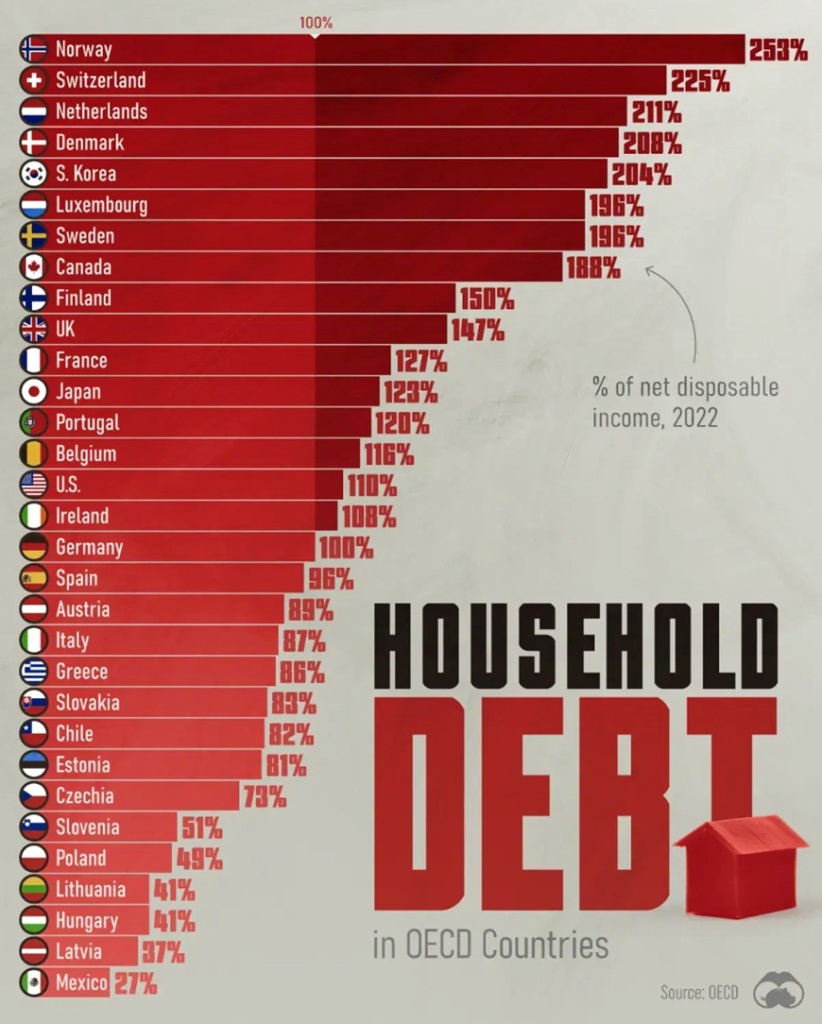

Visual Capitalist linked to a table by Voronoi showing household debt as a percentage of income in 2022, across 38 OECD countries, although data was not available for all of them.

The key takeaway is that household debt is generally higher in developed nations due to greater access to credit, such as mortgages and credit cards; a higher cost of living, and a more consumer-oriented culture.

It may come as a surprise to learn that household debt held by Americans is actually lower than Canada, Japan, South Korea, and several European countries including Norway, which topped the list. The US is 15th at 110%, sandwiched between Ireland and Belgium.

Source: Voronoi

The Norway model

Norway, says Voronoi, has such a high ratio of household debt to disposable income, 253%, for three reasons:

- High rate of home ownership (many have mortgages)

- High incomes (which allow people to take on larger debts)

- Interest paid on debt is tax deductible

The last one is a bit of an eye-opener.

Whereas in North America banks discourage high debt accumulation by charging high interest on credit cards (>20% usually) and putting “stress tests” on mortgage applicants, in Norway they appear to encourage debt by making the interest paid tax deductible.

According to the Norwegian Tax Administration, interest paid on mortgages, student loans, car loans, consumer loans, loans from your employer or a family member, and even loans outside Norway, are all tax deductible.

Compare this situation to Canada. It used to be when you applied for a mortgage, the bank looked at your disposable income (money left after all essential expenses were paid) and compared it to your debt level. If your debt was 25% of your disposable income or higher, you generally didn’t get the loan. You were considered too high a credit risk.

Now, according to the above graphic, in Canada the percentage of net disposable income has risen to 188%. Let’s take another example. Suppose you make $100,000 a year but after all your essential expenses are paid, you are left with $40,000 – your disposable income. At one time you were only allowed to have 25% of that as debt, i.e., $10,000, to qualify for a mortgage. Long gone are those days.

Now in Canada, household debt as a percentage of net disposable income is 188%. You’re still making $100K, your net disposable income is still $40,000 but the level of debt you are carrying is 75% of your income.

In Norway the current level of household debt is 2.5 times net disposable income. Using the same figures in the Norway example above, let’s say your 1,000,000 Kr salary after paying essential expenses leaves you 400,000 Kr. 253% of 400,000 is 1,012,000 Kr. Your level of household debt is roughly the same as your annual salary, even though you still have 400,000 Kr of disposable income with which to pay down your debt.

No wonder the Norwegian government made interest on debt tax deductible!

The US government wants to kick the debt can down the road, they don’t want to deal with it, and aren’t going to deal with it, so the first thing to do is start to lower interest rates back to their Goldilocks 3% range. The US Fed is going to start a rate lowering cycle this month and other countries have already started.

The next step would be making household debt tax deductible like in Norway.

A much more extreme way of handling the crushing US national debt burden would be to simply get rid of it. Wipe it off the books.

Debt Jubilee

A cross-the-board ‘Debt Jubilee’ might sound radical, but a reading of history shows that retiring debt can actually make a country’s economy, and its indebted citizenry, all the better for it. There is even a relatively recent example. The Jubilee 2000 coalition managed to get the G8 to agree to write off $100 billion in debts that developing countries owed to developed nations.

The term ‘Jubilee’ comes from the Old Testament. The book of Deuteronomy refers to a sabbath year during which any slaves would be freed, and everyone would be allowed to return to their family farms and live off the land. During the Jubilee, all debt obligations would be forgiven — such as land or crops that debtors had pledged to creditors.

In those days, the main creditors were royal families and their close supporters — religious orders and wealthy nobles. Thus, canceling debts really only meant snuffing out debts owed to themselves. As explained by Vox, What the king lost in immediate payment, he got back in encouraging a land holding peasantry, who could pay future taxes and provide the backbone of the army. Moreover, rivals to the Crown, foreign enemies or internal upstarts, could foment rebellion by threatening to cancel debts themselves, if the new Monarch did not do so first.

The main economic justification for a modern Debt Jubilee is simple. With debts forgiven, governments could spend the money currently devoted to interest and principal repayments on worthwhile programs; businesses would suddenly be freed from debt bondage and could expand/ hire more staff; and households would have more disposable income, all of which would, in turn, increase aggregate demand and encourage economic growth.

Billionaire investor and hedge fund manager Ray Dalio, in his book ‘Principles for Navigating Big Debt Crises’, argues that when interest rates can’t go any lower and QE has already been tried, a central bank’s last resort is to provide relief for the common people.

We have already reached this point and an outright cancelation of sovereign debt shouldn’t be ruled out.

During the Great Depression, France and Greece had about half of their national debts written off completely. In 1953, the London Debt Agreement between Germany and 20 creditors wrote off 46% of its pre-war debt and 52% of its post-war debt. The country only had to repay debt if it ran a trade surplus, thus encouraging Germany’s creditors to invest in its exports, which fueled its post-war boom. As we pointed out, in 2000, $100 billion worth of debts owed by developing countries were wiped off the books.

Again, this is not as far-fetched as it sounds. Because we live in a fiat monetary system, currencies are not backed by anything physical; the reserve currency, the US dollar, was de-coupled from the gold standard in the early 1970s. It’s not like a raid on vaults full of gold, which have an inherent, physical store of value.

In reality there is nothing preventing central bankers from doing a complete global reset, putting all debt back to zero.

The benefits of a Debt Jubilee would accrue to governments no longer bound to austerity programs; businesses that could invest in their operations instead of paying interest and principal to corporate bondholders; and taxpayers, who would benefit from increased social spending and higher household disposable income.

Garth Turner argues that erasing people’s debt is the same as cutting their taxes, the effect being the same — a marked increase in spending:

It actually means interest rates can go up to stem the tide of new borrowing because the economy gets a shot from the jubilee…. Indebted consumers spend money on loan payments, not on new Silverados or appliances. So, a debt holiday would actually boost the economy as a whole, helping employment, corporate profits, wages, markets and investors.

Of course, not everyone wins from a Debt Jubilee. The losers would include credit card companies, auto manufacturers and banks, all of which would lose the value of the debt which for them is an asset. But they would not hurt for long, recovery would start immediately as consumers goosed the global economy with new, and massive amounts of spending.

Conclusion

Imagine what might happen from following Norway’s example and making interest paid on debt tax deductible? The US economy would boom and the demand for US Treasuries would skyrocket, pulling up the value of the dollar. The rise in economic growth would more than make up for the reduced amount of taxes brought in by the IRS.

Imagine what could be achieved if all the central banks acted together in retiring all the world’s debt — all $315 trillion of government, corporate and household loans. Of course the financial institutions would balk; their hands would need forcing. But the effects on the economy would be immediate and profound. Interesting that CB’s are huge gold buyers.

Central bank gold demand in H1 was the highest on record World Gold Council

Governments, businesses and households would finally be free of the debt shackles that constrict their ability to grow. They could start borrowing and spending all over. And why not? What most think of money isn’t money, it’s credit created by a bank, it’s ones and zeros on a computer represented by paper and coins.

Richard (Rick) Mills

aheadoftheherd.com

subscribe to my free newsletter

*******