Sign up for daily news updates from CleanTechnica on email. Or follow us on Google News!

Everybody wants to do something about carbon emissions but few know how. We want to do better, but it is easier to just keep on doing what we have always done than to put the time, effort, and money needed into making changes. Utility companies that supply fossil gas — incorrectly known as “natural gas” — are under pressure from environmental groups because their product — which is mostly methane — releases carbon dioxide into the atmosphere when it is burned.

Even worse, a great deal of the stuff leaks into the atmosphere, where it remains for 20 years or so. Methane is 80 times more powerful a planet warming agent that carbon dioxide, which means it is accelerating the slide toward warmer global temperatures. But fossil gas utilities have a vested interest in continuing their business model, which brings them substantial profits. Even assuming the executives running those companies are committed to addressing climate change in a meaningful way, they can’t very well walk into a board meeting and suggest shutting down the business.

Moving On From Fossil Gas

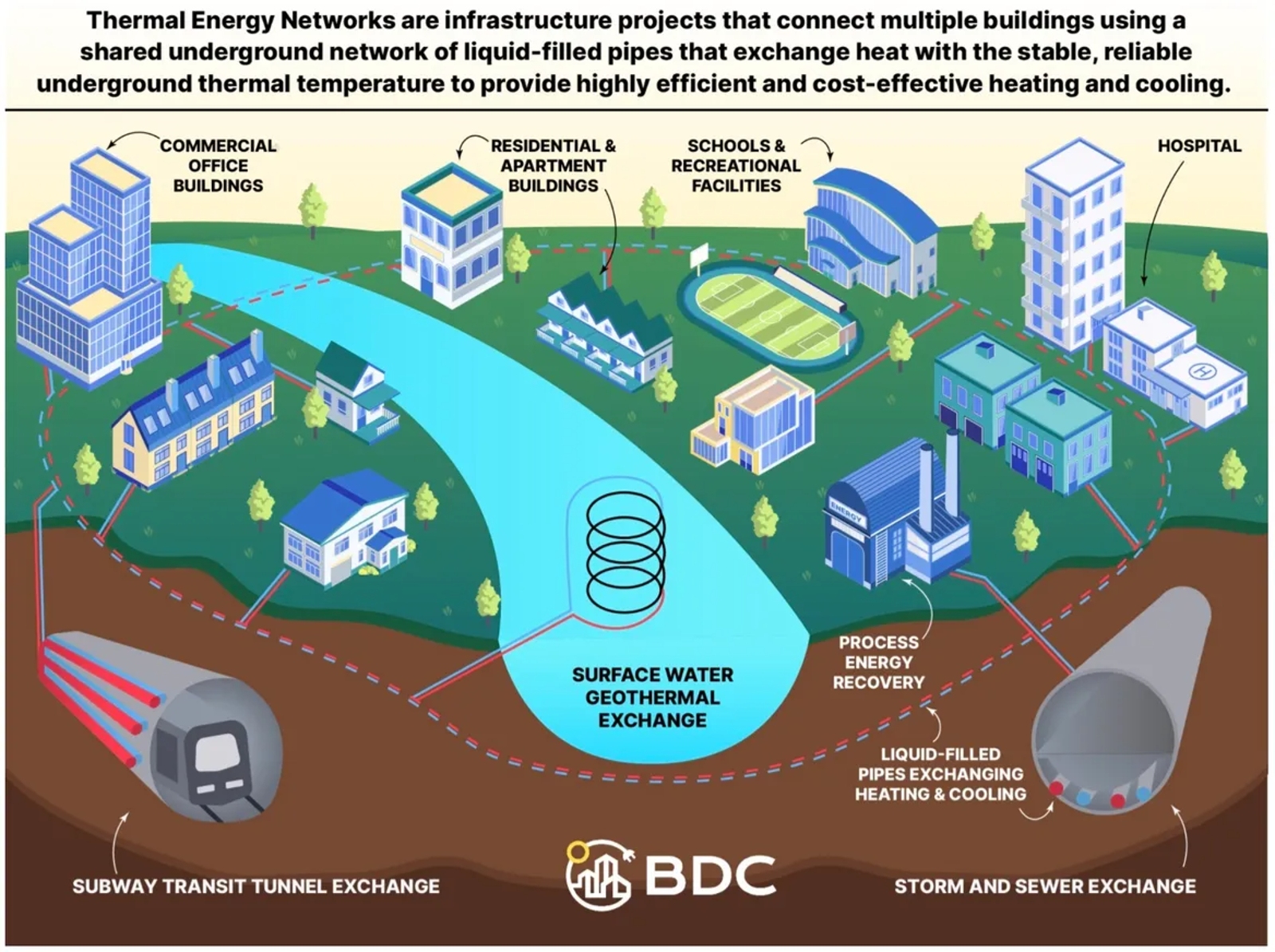

New York State thinks it has a solution to the dilemma. Take all the experience fossil gas utilities have in pipeline construction and building distribution networks and apply it to delivering heat for ground source heat pumps instead. In 2022, the New York legislature passed a law that promotes a number of policies designed to lower greenhouse gas emissions. Among them is a plan to cut carbon and methane emissions from the fossil gas utilities while still carving out a role for those utilities in the decades to come.

They would continue digging trenches, laying pipelines and installing equipment — the same kind of capital investments that earn gas utilities long and stable rates of return today. But instead of flammable and planet-warming gas, those pipes will carry water or other liquids that transfer heat from underground — or from other buildings and sources in the network — that can be used by heat pumps to keep buildings warm.

Why is that important? We know that air source heat pumps — the kind that hang on exterior walls — are more efficient that conventional boilers and furnaces that use fossil fuels. [If you live around Boston, you would say they are wicked efficient.] But what many do not know is that they are even more efficient when they can exchange heat and cold with fluid at a stable temperature rather than from cold outside air. In fact, the Department of Energy estimates such ground source heat pumps reduce energy consumption and emissions by up to 44 percent compared to air source heat pumps and 72 percent compared to standard air conditioning equipment. Now do we have your attention?

While that is exciting news, most building owners would struggle to afford the cost of drilling boreholes and installing pipes for their own geothermal heat pump systems, or to craft contracts with their neighbors to build and share underground networks. That’s why New York’s approach to adapting the gas utility infrastructure holds so much promise. Doing so will help individual homeowners and businesses share in the costs and reap the rewards, Lisa Dix, New York director for the nonprofit Building Decarbonization Coalition tells Canary Media.

Enabling Legislation

Her group advocated for the Utility Thermal Energy Network and Jobs Act that was passed by the New York legislature in 2022. In response to that legislation, utilities in New York state submitted plans last month for 13 pilot projects designed to transform fossil gas pipelines into infrastructure that can power clean, carbon free heat pumps. These underground thermal networks range from dense midtown Manhattan commercial centers to low income housing, and from neighborhoods in the Hudson Valley to the upstate town of Ithaca, home to Cornell University. The results of these pilot projects could help other communities understand how to apply the technology to themselves.

Con Edison, the utility serving New York City and Westchester County, has proposed three projects taking on some of the most challenging urban settings, including the landmark Rockefeller Center. Con Ed plans to convert three large commercial buildings from the utility’s district steam heating network to heat pumps. These heat pumps would draw on water that’s warmed up by waste heat from sources including the sewers, data centers and cooling systems of adjoining buildings.

“There are some misconceptions out there. People think you have to drill a million boreholes to capture underground heat,” Dix said. “But you can get your heat from different sources. You can get it from the subway. You can get it from the sewer. And it’s going to help decarbonize Con Ed’s steam system if we do it right.”

30 Rock Is On Board

Real estate company Tishman Speyer, the owner of 30 Rockefeller Center, is a key partner in the project. The firm has a strong incentive to participate because the project could lower the cost of complying with New York City’s Local Law 97, which requires all large buildings to reduce their carbon emissions by 40 percent from 2019 levels by 2030. Hitting those targets will require an estimated $18.2 billion in investment in alternatives to fossil gas fired boilers and furnaces.

Real estate company Tishman Speyer, the owner of 30 Rockefeller Center, is a key partner in the project. The firm has a strong incentive to participate because the project could lower the cost of complying with New York City’s Local Law 97, which requires all large buildings to reduce their carbon emissions by 40 percent from 2019 levels by 2030. Hitting those targets will require an estimated $18.2 billion in investment in alternatives to fossil gas fired boilers and furnaces.

Shared networks could significantly reduce the cost to individual buildings, but property owners “don’t want to deal privately with all that permitting — they want the utility to deal with all that,” Dix said. When looking for large scale conversion of entire neighborhoods to low carbon alternatives, “utilities make the most sense to do this,” she added. “They’ve got rights of way, they have the permitting authority, they have access to capital, and they have the workforce, which is already unionized.”

Another Con Ed project in Manhattan’s Chelsea neighborhood plans to get 100 percent of heating, cooling and hot-water needs for a low-income multifamily residential building from a nearby data center. “We can have a data center literally heating an entire multifamily building or a big skyscraper,” Dix said.

Three other states — Colorado, Massachusetts, and Minnesota — have passed laws that allow or mandate gas utilities to undertake thermal energy network pilot projects. Illinois, Maine, Vermont, and Washington are exploring similar laws. And 13 gas utilities have created a Utility Networked Geothermal Collaborative to explore more options.

Fossil Gas Utilities Are Ideal

Fossil gas utilities are ideal for installing thermal energy networks at scale, said Audrey Schulman, co-executive director of the Home Energy Efficiency Team in Cambridge, Massachusetts. They have gas the workforce, expertise, and access to capital needed to build the interconnected underground networks needed. They are already spending billions of dollars a year on fossil gas pipeline expansions and repairs that will inevitably become “stranded assets” long before their costs are paid back by customers, she says. “The whole thing is about setting up the regulatory structure by which we get off gas and onto something else.” Below is a brief video put together by HEET that does a nice job of explaining how the process works.

Despite the New York law, fossil gas utilities in the state have spent $5 billion on infrastructure investments and identified $28 billion in pipeline replacement plans since it was passed. This disconnect between climate imperatives isn’t limited to New York. The Brattle Group found in a 2021 report that fossil gas utilities in the US may face up to $180 billion in pipeline investments over the coming decade that may not be recoverable.

Obligation To Serve

Like many other states with decarbonization mandates, New York has offered hundreds of millions of dollars in incentives for heat pumps and building electrification, and has imposed regulations limiting the expansion of fossil gas to new buildings. But according to a 2023 report from the Building Decarbonization Coalition, this “house-by-house” approach could end up leaving gas utilities and regulators in a bind — being forced to maintain expensive gas distribution networks to supply fuel to a dwindling number of customers.

The customers that remain, meanwhile, will bear a greater and greater proportion of the cost of paying off those gas investments, leading to a vicious cycle of cost increases being imposed on people who can’t afford to make the switch to heat pumps on their own. Those left-behind customers are more likely to be lower income earners already struggling to afford increasingly expensive utility bills.

One obstacle is so called “obligation to serve” laws in existence in many states. In exchange for utility companies being awarded a monopoly, they are required to provide service to anyone in their territory who requests it. That obligation is a core part of a utility’s mission, but its strict application could allow a single customer in a neighborhood slated for a thermal energy network to stymie the entire project. Altering laws now on the books in New York, Massachusetts, and other states to allow utilities to switch customers from gas to thermal energy network service without triggering “obligation to serve” objections will be an important part of the transition process.

In New York, the Utility Thermal Energy Network and Jobs Act suspends that law for the pilot projects now being considered, Dix said, but additional legislation will be needed to extend that shift to the state at large. In Massachusetts, the Home Energy Efficiency Team and other environmental and community groups are endorsing a “Future of Clean Heat” bill that would make similar changes.

The efficiency benefits of these networks can also provide significant relief to power grids that will experience massive growth in demand from building heating and electric vehicles. Department of Energy research has found that installing geothermal heat pumps in nearly 80 percent of U.S. homes could reduce the costs of decarbonizing the grid by 30 percent and avoid the need for 24,500 miles of new transmission lines by 2050.

The Takeaway

Converting fossil gas distribution systems to support ground source heat pump systems is a bold idea. For the utility companies, it is a way for them to continue serving the community and making a profit by doing so while decarbonizing their operations. It offers a way to maximize the efficiency gains heat pumps make possible, while reducing climate disrupting emissions.

Such bold thinking is to be applauded. Doesn’t it make more sense to pursue creative solutions like this rather than pinning the hopes for a sustainable Earth on dangerous geoengineering schemes? The utility industry could see this as a win/win situation but many of those utilities are bitterly opposed to the change. They are afraid of the future for their own selfish reasons and worried about their profits rather than building a sustainable human community.

Perhaps when they learn a transition away from fossil gas can be accomplished without destroying their business model, they will overcome their fears and support rather than hinder such plans. If everybody wins — the companies, the communities, and the Earth — that would be the best of all possible worlds.

Have a tip for CleanTechnica? Want to advertise? Want to suggest a guest for our CleanTech Talk podcast? Contact us here.

Our Latest EVObsession Video

I don’t like paywalls. You don’t like paywalls. Who likes paywalls? Here at CleanTechnica, we implemented a limited paywall for a while, but it always felt wrong — and it was always tough to decide what we should put behind there. In theory, your most exclusive and best content goes behind a paywall. But then fewer people read it!! So, we’ve decided to completely nix paywalls here at CleanTechnica. But…

Thank you!

CleanTechnica uses affiliate links. See our policy here.