Sign up for daily news updates from CleanTechnica on email. Or follow us on Google News!

The basic facts about hydrogen are well known. It has the ability to significantly reduce emissions from the steel and cement industries. As a power source, it creates no waste products other than water and heat. While the US struggles to find ways to reduce its carbon and methane emissions, hydrogen keeps coming up as one of the best ways to do that. But unless it is made from renewable and sustainable sources, it creates huge amounts of carbon emissions, making the cure worse than the disease.

The Inflation Reduction Act of 2022 creates the opportunity for up to $100 billion in federal tax and production credits, known collectively as Section 45V credits. Now, $100 billion is a lot of money, which means those who have no right to it will try to game the system in order to line their own pockets with some of that lovely federal money even if they don’t deserve it. Not surprisingly, two of the world’a largest fossil fuel companies — ExxonMobil and Saudi Aramco — want Uncle Sugar to dole our a big chunk of the money to them so they can make dirty hydrogen from methane.

But won’t that create enormous amounts of carbon emissions? Yes, it will, but the companies are telling the government to relax and not worry, because they are going to capture all that CO2 and bury it deep underground, or under the oceans, or store it in a hermetically sealed mayonnaise jar under the back porch. What they don’t say is that carbon capture doesn’t work, has never worked, and quite possibly never will work. This is tantamount to J. Wellington Wimpy, a character in the Popeye comic strip, saying, “I will gladly pay you Tuesday for a cheeseburger today.” In other words, it’s a scam. They know it, we know it, but they are hoping the feds won’t know it and will let truckloads of federal dollars flow into their corporate coffers without holding them accountable. Did we mention this is a scam?

Not Everything That Could Use Hydrogen Should Use Hydrogen

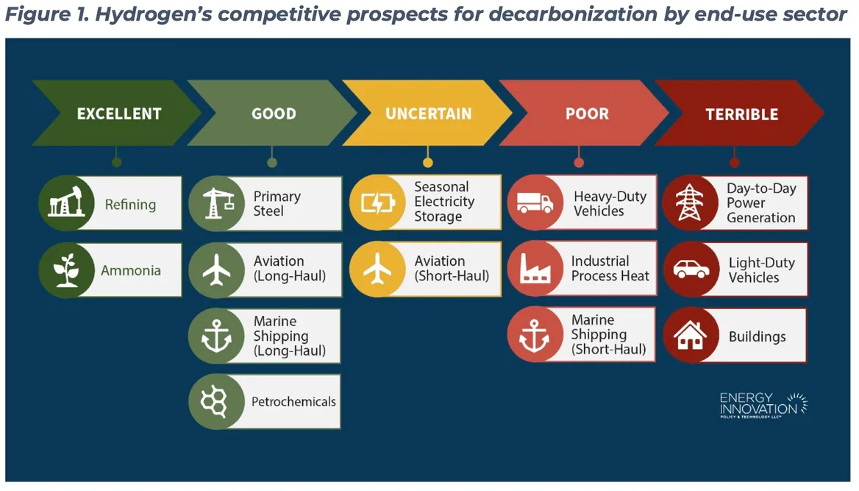

In August, Energy Innovation published a report entitled Hydrogen Policy’s Narrow Path — Delusions and Solutions. “We need clean hydrogen to fulfill our climate goals, but this will happen if and only if it’s truly clean and applied to highest value applications,” Dan Esposito, the author of the report, told Canary Media. He detailed three policy principles to make that happen. “One is subsidizing truly clean hydrogen production. Two is investing in only high value uses. And three is reversing support for hydrogen’s low value uses. By straying from any of these components, you could reverse or delay or raise the cost of emissions reductions.” The chart below clearly delineates what things Esposito believes hydrogen should be used for and which it should not.

US clean hydrogen policy isn’t necessarily set up to support those principles today. It focuses on bolstering low-carbon hydrogen production, which has spurred conflicts between groups that want looser rules to maximize the industry’s growth and those that want stricter rules to limit greenhouse gas emissions. But the US has said far less about how clean hydrogen should be used and how to tell which applications are true pathways to decarbonization and which ones are dead ends.

Esposito’s analysis aligns with the hydrogen ladder created by Michael Liebreich, head of Liebreich Associates and co-founder of clean energy analysis firm BloombergNEF. In simple terms, high-value uses are those which “in 20 to 30 years, hydrogen will still have value competing on a level playing field with other technologies,” Esposito said. Almost all those high-value uses are industries that either need clean hydrogen to replace the methane-derived product they are using today — mostly steel, refining, ammonia, and petrochemicals — or sectors unable to easily replace fossil fuels with electricity, as with aviation and marine shipping.

Electrify Everything Is Still Rule One

Low-value uses tend to be good candidates for direct electrification. That means hydrogen faces harsh competition from cheaper solar and wind power. Building heating, road transportation, and electricity generation and storage all fall into this category. In these industries, “hydrogen is not competitive today, and the long term trajectories on cost and performance strongly suggest that when everyone is back on a level playing field — with everyone or no one getting subsidies — hydrogen will not be able to play even a small role in the market,” Esposito said. The US Department of Energy has also emphasized the need to target “strategic, high impact uses for clean hydrogen.”

The idea of using federal policy to restrict the growth of hydrogen production and usage is contested by a number of pro-hydrogen industry groups — including some backed by fossil fuel companies — that have argued for encouraging the broadest possible uses of hydrogen while the industry gets off the ground. That includes coalitions set to receive $7 billion in federal funding for the DOE’s hydrogen hub projects. They have asked the Biden administration to loosen its strict proposed rules for assessing the greenhouse gas emissions impact of hydrogen production.

Such disputes complicate efforts to focus policies on supporting high-value uses and discouraging low-value uses, Esposito said. He emphasized that it is not good policy to ignore the economic and thermodynamic realities that make hydrogen a bad choice for many industries now being asked to commit to using it. The problem is that “the six good and excellent uses are difficult to break into,” Esposito said. “You’re talking about giant industrial complexes making investment decisions that last decades and have really tight margins.”

A 2023 analysis by the Energy Futures Initiative found that today’s major hydrogen-using industries will need clean hydrogen to be much cheaper than dirty hydrogen in order to cover the cost of retrofitting their facilities and building new infrastructure to use it. Lower-value uses are tempting near-term targets. It’s much simpler to blend hydrogen into existing methane pipelines or to use it to fuel power plants owned by utilities that are also participants in hydrogen hubs, for example. The subsidy of up to $3 per kilogram contained in the Inflation Reduction Act’s 45V tax credit program could make clean hydrogen economically attractive for those lower-value uses, but that subsidy is only intended to remain in place for ten years.

It may take much longer than that for hydrogen markets to develop and for the cost of green hydrogen to become cost competitive with other fuels. Once they expire, what once looked like a cost effective alternative to electrifying building heating, industrial process heating, or transportation “looks like a much more expensive product,” Esposito said. Meanwhile, “you’ve made no progress toward getting to these high value uses.”

Political Support For Hydrogen

Support for the 45V subsidies is all over the political map. Oil & Gas Watch reports that in July, 13 Democratic senators wrote to Treasury Secretary Janet Yellen asking the department to provide more flexibility in meeting the requirements for new clean power in the same regions as hydrogen production facilities. “Without significant changes to the draft guidance … one of the most powerful job creation and emission reduction tools in the IRA will likely be hamstrung,” the senators said. Yet, in September, 66 Senate and House members led by Rhode Island Senator Sheldon Whitehouse, urged the IRS to hold to its clean energy guidelines for tax breaks, which “remain critical to ensuring that 45V does not increase net carbon pollution. Taxpayer dollars must not blindly support all kinds of electrolytic hydrogen or we risk eroding climate progress and further subsidizing the fossil fuel industry at the expense of environmental justice and American consumers,” they wrote in a letter to Yellen. “45V should also not blindly support the production of hydrogen from fossil fuels.”

Some major companies have said they are planning projects that will fully meet the requirements and have warned that others have proposals that will not. Air Products, a Pennsylvania-based industrial gases company that calls itself the “world’s leading supplier of hydrogen,” said during an IRS meeting in March that some companies are “asking you to lower the bar and subsidize, at taxpayers’ expense, investments in hydrogen that will increase emissions.” Eric Guter, vice president of Air Products, said, “Some of these companies are the largest, most technically capable organizations in the world but claim they can’t do what Air Products is already doing. Air Products is planning a $4 billion green hydrogen facility in Texas that will not use natural gas. However, it is also planning separate projects that would produce hydrogen from natural gas, which illustrates how complex this issue is.”

Hydrogen Hubs In America

The debate over the tax credits affects seven proposed regional hydrogen hubs sponsored by the Department of Energy that are meant to serve as a backbone of a new hydrogen energy system in the U.S. Each hub is meant to represent a network of facilities that produce hydrogen, pipelines, and storage systems to get that hydrogen to end users, and facilities that use hydrogen for heavy industry, such as generating power or producing fertilizer.

Some fossil fuel companies appear to be balking after initial enthusiasm for these hydrogen hubs. In December, energy company CNX pulled out of an ammonia project in West Virginia billed as an anchor for the Appalachian Regional Clean Hydrogen Hub, in part citing uncertainty over the 45V rules. Xcel Energy, the largest private company behind the Heartland Hydrogen Hub, has said it might have to reduce or cancel plans and asked for more flexibility from the IRS. In a February letter to the Treasury Department, leaders of all seven proposed hydrogen hubs said the “proposed guidance (including the rules incentivizing clean energy-based hydrogen) poses a risk to the ability of the US to be a global leader in the hydrogen economy.”

Hydrogen And Clean Energy

There are various techniques for making green hydrogen in the lab, but for now and into the foreseeable future, the only way to do it is by passing electricity through water to break it into its components — hydrogen and oxygen. The process is well understood and proven to work, but it has one drawback. It takes a lot of electricity to make hydrogen from water in commercially significant amounts. Where is that electricity going to come from? Many hydrogen entrepreneurs think it will be as easy as calling up the local utility and asking it to send a few billion kilojoules of electricity over. The truth is, however, that if green hydrogen becomes a thing, it will suck up most of the available green energy, leaving little left over for other purposes.

According to E&E News, some environmentalists are concerned that diverting existing clean electricity to make hydrogen will cause emissions to increase by forcing grid operators to draw more heavily on thermal generators to make up the difference. “We’re talking several 100 millions of metric tons of carbon emissions over the lifetime of the credits with weak rules,” said Rachel Fakhry, policy director for emerging technologies at the Natural Resources Defense Council. “That is half of what the U.S. currently emits in one single year of carbon emissions from its power plants.”

That’s why environmentalists and even some in the energy industry have coalesced around a new requirement known as “additionality.” That provision would require hydrogen producers to not just use clean energy, but new clean energy generation added to the grid. The administration says it is considering the provision carefully. “It’s a really important consideration, and it’s something that I know we’re weighing,” Energy Secretary Jennifer Granholm said of additionality in June of 2023. The idea is supported by the American Clean Power Association but opposed by the nuclear power industry, which sees itself being shut out of the market for electricity to power electrolyzers by the upcoming rules.

A Labyrinth Of Rules

One thing most people can agree on is that more rules lead to more expenses. If green hydrogen is the answer to lowering carbon emissions, at least partially, the more complex the regulatory compliance process, the more money will be spent on meeting the rules, leaving less available for actual production. According to Ascent, a global business consultancy, 50% of respondents to a Risk Management Association survey said they spend 6 to 10% of their revenue on compliance costs. Large firms report the average cost of compliance is approximately $10,000 per employee. Some may quibble over those numbers, but compliance clearly has costs and they are not trivial.

One idea put forward it that the rules include regional requirements on renewable energy credits. This would ensure that hydrogen producers are buying credits from renewables close to their production sites, rather than from cheaper alternatives across the country that have no direct impact on the project’s emission profile. Another restriction being discussed is requiring hydrogen producers to only turn on their electrolyzers when renewable energy projects are actually generating electricity on the grid, thereby matching the production of hydrogen with clean energy generation.

The Takeaway

Hydrogen may be ideal for cleaning up emissions in high-polluting industries like steel and cement, but to get there, it needs to be cost competitive, and right now it is anything but. Fossil fuel companies want to use the same tired old playbook of saying something is “green” when it is not. Hydrogen from methane deserves no consideration from policy makers at all. Neither does hydrogen for use cases that can easily have their needs met by using renewable energy directly rather than using electricity to make hydrogen that gets turned back into electricity later.

The Treasury Department has its hands full trying to help the hydrogen industry get off the ground it the US without squandering taxpayer money on projects that rely on the alchemy of carbon capture to become viable. The subject of “additionality” should be part of the picture and perhaps extended to data centers, which are sucking up vast amounts of electrons to power the AI craze.

Regulators do not have a crystal ball to tell them which technologies will succeed and which will fail, but they should have the good sense not to throw money away on ideas that are too clever by half, such as carbon capture. We can expect the final rules from Treasury that will determine who the winners and losers are shortly.

Have a tip for CleanTechnica? Want to advertise? Want to suggest a guest for our CleanTech Talk podcast? Contact us here.

Latest CleanTechnica.TV Videos

CleanTechnica uses affiliate links. See our policy here.

CleanTechnica’s Comment Policy