The Bretton Woods financial system collapsed in 1971 when President Nixon severed the link between the dollar and gold – the US dollar was now a fully floating fiat currency and the government had no problem printing more money. With gold finally demonetized the US Federal Reserve and the world’s central banks were now free from having to defend their gold reserves and a fixed dollar price of gold.

The Fed could finally concentrate on achieving its mandate – full employment with stable prices – through targeted levels of inflation. The Fed’s ‘Great Experiment’ had begun. The objective was to level out of the business cycle by keeping the economy in a state of permanent boom — gold’s “chains of fiscal discipline” had been removed.

But there was a problem. Because of the massive printing of the US dollar to cover the Vietnam War and welfare reform costs, Nixon worried about the strength of his country’s currency. How do you keep the US dollar as the world’s reserve currency, keep demand strong, if one, you remove gold’s backing, and two, print it into oblivion?

Recognizing that the US, and the rest of the world was going to need a lot more oil, and that Saudi Arabia wanted to sell the world’s largest economy (by far the US) more oil, Nixon and the Saudis came to an understanding in 1973 whereby Saudi oil would be purchased in US dollars. In exchange for Saudi Arabia’s willingness to denominate their oil sales in greenbacks the United States offered weapons and protection of their oil fields from neighboring nations.

Global oil sales in US dollars caused an immediate and strong global demand for US dollars — the “petrodollar” was born.

End of a phantom deal

Was there actually an agreement requiring Saudi Arabia to price its crude-oil exports in US dollars? The Internet and social media in mid-June crackled with news that a 50-year-old “petrodollar” pact between the two nations had expired— opening the door for the Saudis to sell their oil in other currencies, thus dealing a fatal blow to the petrodollar.

However, it was fake news; such an agreement never existed.

Morningstar quoted Paul Donovan, chief economist at UBS Global Wealth Management, saying that, while there was an agreement signed in June of 1974 it wasn’t concerning currencies, instead it was about what the Saudis would do with their newly found wealth.

The United States-Saudi Arabian Joint Commission on Economic Cooperation, established in June 1974, did not agree to sell the kingdom’s oil in dollars, but rather, to channel the new wealth following the 1973 energy crisis, into the US Treasury market.

The US would purchase oil from Saudi Arabia and furnish it with American military aid and equipment, and the Saudis would invest their oil proceeds in US Treasury bonds. (Project Syndicate, July 5, 2024)

As Bloomberg opinion writer Javier Blas states,

In its original incarnation, the petrodollar was about recycling oil money, and far less about what currency crude was priced and invoiced in. The Saudis poured money into American sovereign debt, helping Washington to finance its deficits, and in return the US offered secrecy about the financial dealings and military protection.

Still, Morningstar notes, “the notion that the petrodollar system largely grew organically from a place of mutual benefit — rather than some shadowy agreement established by a secret cabal of diplomats — remains a matter of indisputable fact.”

Author Joseph Adinolfi argues that, while it’s true the Saudis have recently been more open to accepting currencies other than the dollar as payment for its oil sales — such as Chinese yuan — even if such an agreement were reached, Saudi Arabia’s close economic and military ties to the US, and the fact that nearly the entire global system for financing, insuring and transporting oil requires dollars, will likely continue to incentivize the kingdom to continue seeking dollars.

Donovan says “the more important question is does Saudi Arabia change the currency in which it holds its [foreign exchange] reserves, which at the moment is majority dollar.”

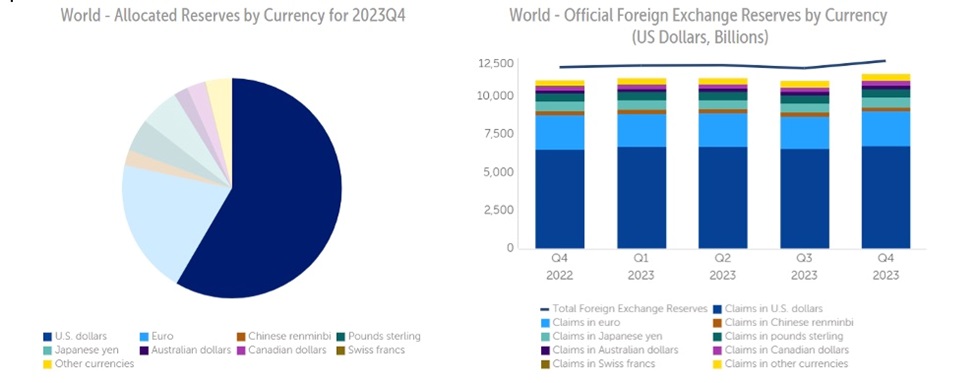

While the dollar’s share of global reserves has gradually declined — more on that below — no rival currency has challenged its dominance, according to the latest data from the International Monetary Fund.

Another arrow in the pro-petrodollar quill is the fact that Saudi Arabia pegs its currency to the greenback. Maintaining a fixed exchange rate to the dollar requires large dollar reserves.

Bloomberg’s Javier Blas concedes that the petrodollar convention (let’s stop calling it an agreement) made sense in the 1970s when the Saudis had a lot of money and little domestic capacity to absorb it. Sopping up US Treasuries was a system of mutual benefit.

The situation today is different.

First, the United States has become a net exporter of crude oil and no longer relies on imports from Saudi Arabia.

Second, Saudi Arabia no longer has a surplus of money it needs to recycle into Treasuries. The country still borrows heavily in the sovereign debt market but it also sells assets, including chunks of its national oil company, to finance its economic plans.

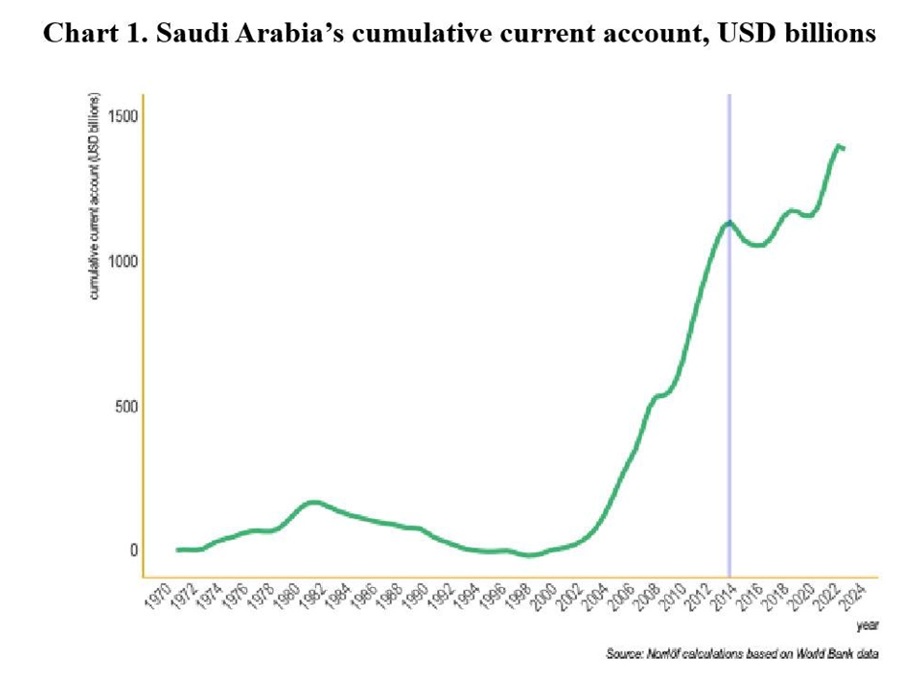

Project Syndicate notes that Saudi Arabia’s cumulative current account is close to $1.5 trillion (see Chart 1), suggesting sizable dollar-denominated holdings.

Riyadh still holds significant hard currency reserves, some of them invested in US Treasuries, but it’s not accumulating them anymore. China and Japan hold much more Treasury debt than Saudi Arabia.

So in that way, the petrodollar’s role has weakened.

Source: Marketwatch

Blas argues the strength of the petrodollar may be diminished but it’s not going away.

“I don’t expect the petrodollar to die anytime soon,” he writes. “In my conversations in the Middle East, I don’t sense any desire to shift away from the American currency for oil sales.”

“Shifting to other currencies has more problems than advantages — and by other currencies I mean the euro, sterling, the Swiss franc or the yen. Embracing the Chinese currency, as the blogosphere suggests, would be even more difficult. The greenback is freely convertible, the yuan isn’t; the dollar is liquid, the yuan isn’t. Enough said.”

(China and India have strict capital controls, preventing their currencies from getting very far as dollar replacements — Rick)

The Carson Group notes the irony of calling the end of the petrodollar when the United States and Saudi Arabia are on the verge of signing an historic security agreement. According to US and Saudi officials, the draft treaty is modeled loosely on Washington’s mutual security pact with Japan:

In exchange for the U.S. commitment to help defend Saudi Arabia if it were attacked, it would grant Washington access to Saudi territory and airspace to protect U.S. interests and regional partners. It is also intended to bind Riyadh closer to Washington by prohibiting China from building bases in the kingdom or pursuing security cooperation with Riyadh, the officials said.

Dollar bulls

The Carson Group lists three reasons why the US dollar will remain dominant and is unlikely to be dethroned anytime soon:

- One, global trade is dominated by the US, China, and the EU. But it’s massively skewed, with the US importing much more than it exports. China is the dominant exporter, but even Europe exports more than it imports. All this means the rest of the world is awash in US dollars — which they receive in exchange for supplying Americans with goods… And what do they do with the USD they receive? They invest them in the most liquid and deepest capital market in the world, the United States of America.

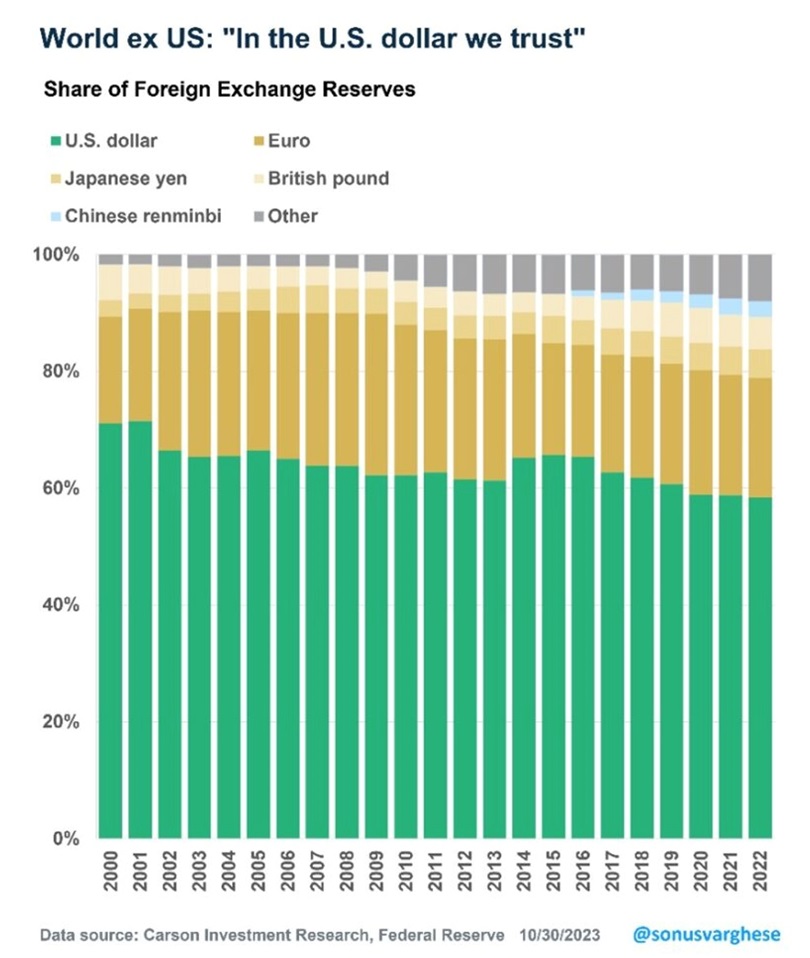

- Two, the world has confidence in the US, and therefore the dollar. This is because the US has the deepest and most liquid financial markets, thanks to the size of the US economy, the strength of the US economy, open trade and capital flows with few restrictions, strong rule of law, property rights, and a history of enforcement. Despite the US making up 25% of the global economy, about 60% of global foreign currency reserves are in USD. It has fallen from 71% in 2000 but remains far ahead of other currencies as the decline in share has been spread across various currencies.

The dollar is on one side of about 90% of the trades in the $7.5-trillion-a-day foreign exchange market. (Barron’s, July 28, 2024)

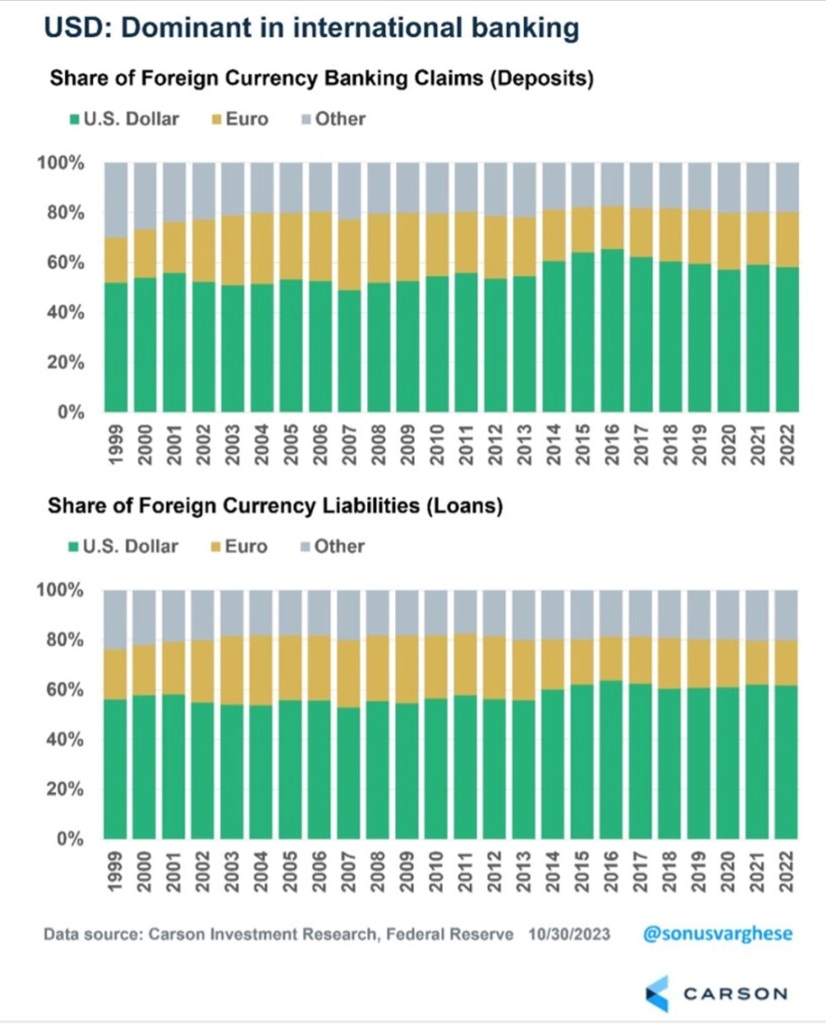

- Three, the USD is dominant in trade invoicing and international finance. Outside of Europe, more than 70% of exports are invoiced in US dollars. That’s unlikely to change anytime soon. Again, everyone wants USD because it’s liquid and “safe”. It also means the USD automatically becomes the dominant currency for international banking. Close to 60% of international foreign currency banking claims are in USD, including bank deposits denominated in foreign currency and loans taken out in a foreign currency. That’s been fairly stable since 2000, and actually increased over the past decade.

Dollar bears

Even though the petrodollar hasn’t actually collapsed since there was never a formal agreement to establish one, there are voices predicting the dollar’s demise. We briefly summarize these arguments.

FXLeaders in June wrote that “The increasing use of local currencies for cross-border payments, particularly by BRICS nations and countries in the Middle East and Asia, is challenging the dollar’s dominance and paving the way for a potential new era in global finance.”

As oil is priced in other currencies, global demand for dollars could decrease. This could weaken the dollar and cause inflation in the US, forcing the Federal Reserve to re-consider raising interest rates.

Also, if foreign governments hold fewer bonds, it could increase borrowing costs for the US government, because bondholders would demand higher interest rates.

The dollar’s share of global forex reserves is certainly worth watching. According to the IMF, it’s fallen from 73% in 2021 to 58.4% in 2023.

Source: FXLeaders

FXLeaders points out a couple more dollar-bearish trends, the first being the traction of China’s Cross-Border Interbank Payment System (CIPS) as an alternative to SWIFT. Second is Saudi Arabia’s strengthened ties with China including $116 billion worth of bilateral trade in 2023. In March of last year, Saudi Aramco sold oil to China priced in yuan for the first time.

A piece by the Atlantic Council writes that, As countries from the BRICS group and regions including the Middle East and Asia increase the use of local currencies for cross-border payments, there is a growing perception that the dollar’s importance in international finance is ebbing, particularly in global oil markets and the use of the petrodollar.

The council agrees with FXLeaders on the importance of a rising China, expressing that the United States’ share of global GDP has declined from 40% in 1960 to 25% today. Meanwhile, China’s economy has surpassed the US in purchasing power parity.

As mentioned the US has become far less dependent on Saudi oil due to shale. By contrast, China has become Saudi Arabia’s largest oil customer, accounting for over 20% of the kingdom’s oil exports.

Finally, there is Saudi Arabia’s willingness to join the BRICS and partner with China and other countries in the mBridge project, to explore the use of central bank digital currencies in cross-border payments.

The Atlantic Council concludes:

In the foreseeable future, the dollar’s dominance will remain. But a gradual democratization of the global financial landscape may be underway, giving way to a world in which more local currencies can be used for international transactions. In such a world, the dollar would remain prominent but without its outsized clout.

We can talk about the relative strength of the dollar compared to other currencies and its role in the financial system as the world’s reserve currency. We agree with those who say that the dollar will likely never be eclipsed by another currency or basket of currencies such as Special Drawing Rights. It is simply too important, valuable, safe, liquid, and its use is too widespread.

The short-term movements of the dollar is another story, especially as they are caused by key elements of the US economy such as interest rates and inflation.

While the USD has recently reached historic heights against several currencies including the euro and the Japanese yen, and a favorable mix of easy fiscal policy and tight monetary policy has fueled the dollar’s rally over the past few years, this is coming to an end as economic growth slows and price pressures moderate.

The Federal Reserve is likely to start cutting interest rates in September, with the easing cycle likely to continue into 2026. The derivative market anticipates about two percentage points in cuts (200 basis points) overall (Barron’s).

Why interest rates must fall

A succession of interest rate hikes have underpinned the high dollar. One of the problems this causes is to increase the American government’s cost of servicing the debt.

According to Congressional Budget Office estimates, net interest payment as a percentage of GDP is projected to reach its highest level in over two centuries.

The OECD says by next year, the US will face the highest cost for servicing its debt among all developed economies.

The need for rate cuts becomes even more apparent when we examine how a year of high interest rates has affected the US economy.

While higher-income households have benefited from a booming stock market, high property values and robust investment yields, corporations are borrowing more, and consumers continue to spend, those with lower incomes are suffering the ill effects.

Bloomberg reports that Americans are searching longer for jobs, and the unemployment rate has inched higher. Small businesses are feeling the pain from costlier loans. And lower-income households are falling behind on payments for their car loans and credit cards.

Interest rates on credit cards hit 22.7% in May.

In the US, housing affordability is near the lowest level in more than three decades, and in Canada, it has become an election issue at both the federal and provincial levels.

According to the National Association of Realtors, with state-side mortgages at around 7%, the monthly payment for a median-priced home climbed to $2,291 in May, compared to $1,205 three years prior.

Hiring has slowed from the overheated levels of two years ago and companies are posting fewer job openings, Bloomberg said. The long-term unemployed, defined as the number of people who have been out of work for 27 weeks or more, rose to 1.5 million in June, the most since 2017 if the pandemic-related jobless hike is excluded.

Companies are continuing to borrow despite the higher rates, but according to Fitch Ratings, the default rate on leveraged loans is projected to rise to 5.0-5.5% this year, the highest level since 2009.

“There’s a tremendous amount of pain and many, many companies that are going bust because of the Fed’s monetary policy,” Bloomberg quoted Hans Mikkelsen, managing director of credit strategy at TD Securities.

Conclusion

How much longer will the US government continue to inflict pain on consumers, which make up 70% of the economy, and small and large businesses, through high interest rates?

In our opinion a rate cut is coming soon, for all the above reasons.

When the Fed cuts rates it will quickly result in lower Treasury yields and a lower dollar, which will kickstart the next bull leg up for precious metals gold and silver.

Of course, I see the BRICS’ reticence regarding Treasury-buying as part of a broader movement to diversify global finance, and chip away at dollar dominance. This is only likely to continue, imo, as the US debt situation continues to worsen, and credit agencies come a-knockin’.

But I also see recent buying by Canada, Europe and the world’s financial centers as a way of propping up the US dollar.

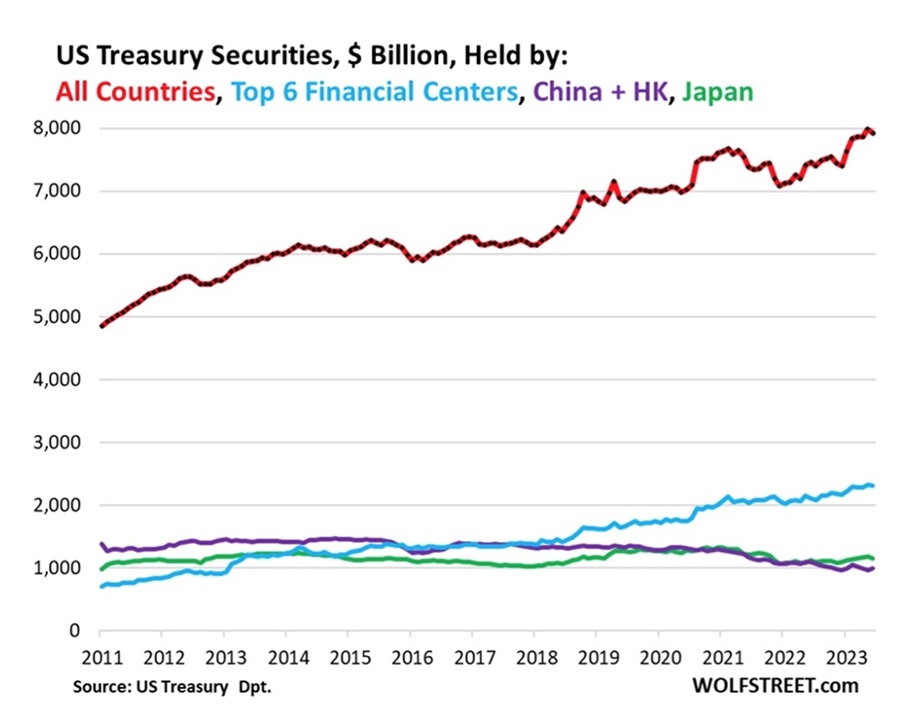

Wolf Street provides charts showing that the top six financial centers (London, Belgium, Luxembourg, Switzerland, Cayman Islands, Ireland) currently hold $2.3 trillion in T-bills, a 9.2% increase year over year.

The countries of the Euro area have also been piling into Treasuries at a furious rate, expanding their holdings from $500 billion in 2011 to $1.58T now, says Wolf Street, adding that year over year, the Euro area’s holdings surged $202 billion, or 14.6%.

France is one of the biggest players, in April reaching a record-high $277 billion compared to Germany’s $87 billion.

Other top foreign holders of Treasury securities include Canada, @ $338 billion, a 36.9% increase year over year, and Taiwan, which increased holdings 5.3% to $257 billion.

Japan holds $1.5 trillion, a 2.2% increase from a year ago, but the key data point is China and Hong Kong combined, which hold 9.1% less Treasuries, year over year, worth $992 billion.

This compares to more than $1.4 trillion between 2012 and 2017.

US dollar dominance and the “exorbitant privilege” the reserved currency provides is not at risk. But in the short term, dollar decline is practically inevitable due to the coming shift in monetary policy.

Richard (Rick) Mills

aheadoftheherd.com

subscribe to my free newsletter

********