Headline interest rates are well-known.

Fed Funds Rate is 5.25% to 5.5%. The 1-month Treasury is 5.5%, the 10-year Treasury is 4.4%, etc.

In other words, it has spiked massively in the last 18 months. The Fed continues to promise “higher, for longer”.

Mainstream theory—also alternative theory—holds that higher interest rates are the bitter medicine needed to cure the economy of inflation.

Never mind that, if you hike the cost of capital, then necessarily the return on capital will follow. By liquidating productive capacity.

Never mind that if you reduce supply, this will not cause prices to fall.

The Quantity Theory of Money holds that if you decrease the number of dollars then prices must fall. And the Fed is hell-bent on this course of action.

It is true that, if you hike the rate of interest, then you will decrease the number of dollars (or at least reduce the rate at which the quantity grows). However, consumer prices are far downstream of interest rates.

Your Noisy Neighbor, The Fed

Let’s make an analogy.

Rising consumer prices are like a loud party, the kind that makes the neighbors keep calling the cops.

Of course, you don’t want to respond directly (this being an analogy to government policy to fix the ills caused by previous government policy).

So you respond indirectly. You change the music to Mozart. Maybe this will cause guests to leave or at least quiet down?

The result, instead, may be that they begin to argue even more loudly.

And now there’s a different problem too. People can’t dance to this “bad” music, so they have an argument in the hallway.

The Fed’s rate hikes are like changing the music. The noise of the party is like inflation. The former does not necessarily have the desired effect on the latter. But whatever, we want to understand what happens next.

Why Did the Dog Not Bark?

In the case of the economy, we have (at least) two problems. One is already obvious. Bond prices (and all asset prices) are inverse to interest rates.

For example, the price of a 30-year Treasury is now down around 50% from its peak in the summer of 2020. Banks buy Treasurys with borrowed money—i.e. with leverage. Leverage is a lot of fun on the way up. But on the way down, you can be Silicon Valley Bank without even thinking about it!

The banks not only lost 50% on these investments, they not only did so with borrowed money, but they compounded this with a third problem. Duration mismatch. They did not borrow 30-year money, matched to their 30-year asset. They borrowed short-term money, such as customer deposits.

They presumed that customers would never transfer those deposits to other banks1. But in the case of Silicon Valley Bank, they did. And the momentum was just getting started to run on other banks, especially small regional and specialty banks like Silicon Valley Bank.

The question, to shamelessly steal a brilliant idea from Sir Arthur Conan Doyle in The Adventure of Silver Blaze, why did the dog not bark in the night?

Why did this run on the small banks not continue?

The Fed has many tricks up its sleeve. And if one of them is not a perfect fit for the job at hand, it can modify it like a clever handyman with chewing gum and duct tape.

A Duct Tape Pawn Shop otherwise known as the Reverse Repo Facility

The Fed has a “reverse repo” facility. This is a pawn shop, where banks can bring Treasurys and get cash. Normally—if the sorry history of central planning by the Federal Reserve is normal—a bank can only get cash based on the market price of the bond. This is not enough for bonds that have fallen 25% or 50%.

But never fear, dear reader, the Fed cut a little notch with its penknife, twisted it around with some bailing wire, and then wrapped it with duct tape! Presto voila, a new reverse repo that pays banks based on the price they originally paid for these bonds!

In other words, though the interest rate today is 4.4% and the price of a 10-year Treasury is down 22% from its high, the Fed will take the bond and pay the bank as if the interest rate were well under 1% and the Treasury price were still back in 2020-land.

Pretty nifty, eh?

Pavlov’s Fed

The second problem is that these rates are administered to businesses in the real economy. These hapless companies have to raise capital to finance new production.

After four decades of falling rates, there was no business case for expansion until each new downtick in rates reduced finance expenses further.

Return on capital was pulled down by falling cost of capital. It is marginally above cost. And now, with rates suddenly much higher, few companies have any case for borrowing.

Worse, most companies who borrowed money to finance production previously have short-term loans. The reason is simple. In a falling-rates environment, no one wants to be locked into higher rates for the long term. Pavlov’s Fed trained their business dogs to salivate for each new downtick.

When this debt must be rolled over—that is, they must borrow at the new, much-higher rate in order to pay off the old low-rate loan when it matures—these companies encounter a problem.

The problem is that they can’t afford the higher rate! They barely made enough money to service the low-interest debt. They don’t make enough to justify the high-rate debt they must replace it with.

Zombie Indulgences

Recall that, back in the halcyon days of zero interest, a massive proportion of corporate debt outstanding was already so-called “zombie”—when profits are less than interest expense.

Now that rates are jacked up to 5.5%, this will zombify companies which had not been zombies previously. Many, many new companies.

Additionally, the credit market is not so indulgent as it was in 2020. Lenders are not so willing to give their money to companies whose profits are insufficient to cover the interest expense.

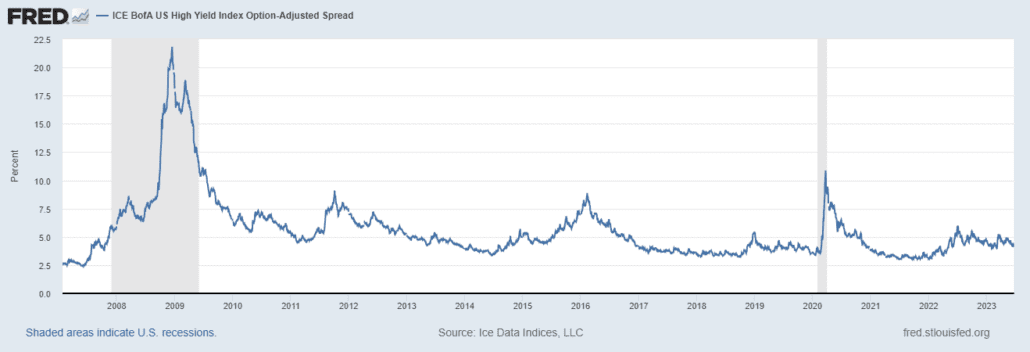

The result we should expect to see is that the spread between junk bonds and Treasurys blows out. It should widen dramatically. This would mean that those low-quality borrowers who can still, somehow, access the credit market must pay much-higher rates compared to Treasurys than before.

Or, put it another way, lenders are incentivized to lend to the Treasury over low-quality borrowers, unless the latter compensates them handsomely for the risk.

The junk-Treasury spread blew up at the time of the great financial crisis and began to blow up at the onset of Covid lockdown. There is no sign of anything like that, today.

This is another non-barking dog, which begs the question, why?

Finding the Junk Answer

Obviously, someone is buying junk bonds. And equally obvious, if we were in a normal economy—if the bust phase of the Fed’s cut-and-hike cycle could be called “normal”—lenders would be pulling back.

Therefore, we should look for the perverse incentive. The moral hazard. The guarantee or backstop of this debt (perhaps implied).

The nudge from the macroprudential regulators. Something that induces lenders to give their money to low-quality borrowers who didn’t make enough profits to service their debts even at zero interest, and now pent-tuply (yes that’s a word, now I’ve coined it!) don’t make enough to cover their interest expense.

What I will present is, admittedly, anecdotal. It is, admittedly, based on private conversations I’ve had. But I offer it anyway.

I liken it to when Darwin found a flower that had a long, skinny trumpet, in the Galapagos Islands. He knew he was looking for a bird or insect that has an equally long and skinny nose.

He found it.

Our regulated—indeed government-dominated—markets were constructed one regulation at a time. In each instance, the government interfered with the normal functioning of the market. It imposes uneconomic restrictions.

This distorts the market because it offers perverse incentives to market participants. Perverse incentives cause perverse behaviors. Perverse behaviors cause perverse outcomes. Perverse outcomes lead people not to question the idea or legitimacy of regulations. No, they lead people to call for another regulation to fix the perverse outcome caused by the previous.

To picture this, put yourself in the shoes of an asset manager, perhaps at a bank or insurance company. The government has granted you a special privilege: your credit paper is to be treated by the market as if it were money. You can borrow at a special “discount window” at the Fed. You can attract depositors easily because they are promised a $250,000 bailout if you go bankrupt. If you get into trouble, the Fed will buy bad assets from you (or reverse repo them). The list goes on.

Now, add one more perverse incentive to the list: falling and too-low interest rates. This both enables you to use greater and greater leverage. And forces you, as you can’t make enough money to survive, without leverage.

You are paid a bonus if your portfolio performs well. But if your portfolio value collapses, they cannot claw back any money from you. So it is literally “heads you win, tails they lose.”

Would you rather lever up 5 to 1, or 10 to 1? Would you rather own a Treasury paying 4.4% or a junk bond paying 8.3%? If you have suffered capital losses due to the drop in Treasury bond prices, you need to recapitalize your balance sheet. You can do that more quickly at 8.3%, obviously.

Wet Blankets and Hot Fires

The regulators know this, of course. And they have all sorts of rules to keep you from using too much leverage, the wrong kind of leverage, and leverage for the wrong kind of asset. For example, if you are buying riskier assets like junk bonds, you need to reserve more capital than if you are buying Treasurys.

What I have heard is that regulators are now encouraging insurers to buy more junk bonds, by either changing these regulations, or at least looking the other way. And at least some insurance company asset managers are taking the bait.

This is a powerful argument that the depositors and insureds, not regulators, should be in ultimate control of what risks banks and insurers take. Regulators, themselves, are subject to many perverse incentives.

To put it plain words, there are pressures to cheat. The Fed is busily hiking rates, but they must be thinking “well, we just mean to slow inflation, we didn’t want that to happen to them!”

So while the Fed sets the fire that can cause the economy to burn down, it is busily throwing wet blankets here and there, bifurcating interest rates.

All this while the interest rates at Monetary Metals remain stable, positive, and paid in gold and silver.

Monetary Fissures are Emerging

By the way, whether it’s intentional or not, one place that does not get any relief, is countries without dollar swap lines. Such as China. The more the Fed tightens, the more acute their dollar shortage. I will not speculate as to whether this is the point of the exercise, merely note that it is real and it is a big deal.

My point today is that there are effectively two different interest rates. For you and me, the interest rate is what we see on the screen. For banks who bought Treasurys a few years ago, for junk borrowers, and for others with special privileges, the interest rate is much lower.

Back in 2012, I wrote an article called Dollar Backwardation. The idea was that we take for granted that a paper dollar bill and a bank dollar deposit trade at par. That they are the same. However, they may, suddenly, not be. Picture standing on a green field of grass. And suddenly, a fissure opens up. It begins to widen. You look down, and see infernal flames. This fissure splits what you had previously thought was an unbroken plains. Or an unbroken monetary system.

In 2013, I wrote an article called Cyprus Collapse Triggers Unintended Consequences. The idea was that we took for granted that a euro in the bank was a euro in the bank. But when the Cyprus banking system collapsed, euros in Cypriot banks were no longer fungible with other euros. A fissure had opened, where no one had thought there could be one.

A fissure in the earth is very dangerous. Leaving aside that you could fall into it, the movement unleashes enormous forces which can knock down buildings, cause drivers to crash into sudden hillsides, rupture gas lines which causes fires, etc.

A fissure in the monetary system is very dangerous. Leaving aside that you can lose money into it, it causes market participants to drastically alter their behavior, which can cause the collapse of financial institutions, gross misallocations of capital, and other collateral damage.

I don’t like to criticize the regulators and Fed officials for being dumb or incompetent, because the focus should be on the impossibility of their job not their poor performance at it. But in this case, I have to conclude by saying that in bifurcating the interest rate, they are like children sitting in a pile of dry straw in a hayloft, playing with matches. They know not what they do.

Make sure to subscribe to our YouTube channel and weekly newsletter to stay up to date on the latest breaking news happening in the markets and how to protect yourself.

*********