Support CleanTechnica’s work through a Substack subscription or on Stripe.

In 1966, Roger Payne heard about recordings made by Frank Watlington, a Navy engineer who in 1958 captured eerie underwater moaning and wailing sounds while manning a top secret hydrophone station off the coast of Bermuda. He was listening for the sounds of Russian submarines, but what he heard were the sounds of humpback whales.

Payne obtained copies of the recordings and discovered the songs repeated themselves. According to Wikipedia, the shortest songs were about six minutes long, while the longest lasted more than thirty minutes and could be repeated continuously for up to 24 hours. When the sounds were converted to graphs, they displayed a definite structure.

Payne and his wife Katharine discovered that all male whales in a given ocean sing the same song, but it changes slightly from year to year. Katharine found the longer songs had structures analogous to rhyming, with key structures repeating at intervals — raising the possibility that the whales were using mnemonic devices to help them remember the more complicated songs.

In 1970, Payne released an album of the whales’ songs entitled Songs Of The Humpback Whale, which sold over 100,000 copies.

In November 1970, Judy Collins — she of the honey voice that so bewitched Stephen Stills — released an album entitled Whales And Nightingales. On one track, she incorporated some of those whale sounds in the hauntingly beautiful “Farewell To Tarwwathie,” a lament that ends with, “I’m bound off for Greenland and ready to sail, in hopes to find riches in hunting the whale.”

The Cetacean Translation Initiative

Following in the footsteps of Roger and Katharine Payne, marine biologist David Gruber has spent decades trying to understand creatures most of us never truly see — protozoa, bioluminescent corals, jellyfish, sharks, and now whales. Inside Climate News reports that in 2020, he founded the Cetacean Translation Initiative (CETI), a nonprofit that listens to and translates the voices of sperm whales. The acronym sounds very much like SETI — the Search for Extra Terrestrial Intelligence group that plumbs the depths of the universe looking for signs of life out there among the galaxies. Whether or not that is a coincidence, we can’t say.

What makes CETI’s work stand out isn’t just the technology, it’s the philosophy behind it. Gruber is known not just for his discoveries but also for his empathy. “He rejects the traditional hierarchy that places humans above other species and believes that scientific research should foster understanding without causing harm or disruption. In practice, he has sought to understand the world from the perspective of animals, once building a camera modeled on a shark’s eye to see the world as they do,” ICN says.

Now Gruber wants to hear the world as sperm whales do and is using AI to decode the recordings the group has made. CETI is a “deep listening experiment” intended to shift how humans relate to the natural world — and how they protect it.

On October 22, 2025, CETI published a paper in Ecology Law Quarterly with the intriguing title, “What if We Understood What Animals Are Saying?: The Legal Impact of AI-Assisted Studies of Animal Communication.” Gruber is among a growing number of Western scientists who support the Indigenous-led “rights of nature” movement, which aims to advance the recognition that individual species and ecosystems have inherent value and legal rights.

Their contributions are helping build a fast growing movement. Countries including Ecuador, Colombia, New Zealand, Panama, Spain, and Uganda already have such laws or court rulings on the books. Western scientists have helped craft some of those laws, grounding them in ecological principles, and have given heft to the movement’s underlying argument that humans are one species in an interdependent web of life — which is antithetical to the thinking of the current leaders of the United States.

Learning How Whales Communicate

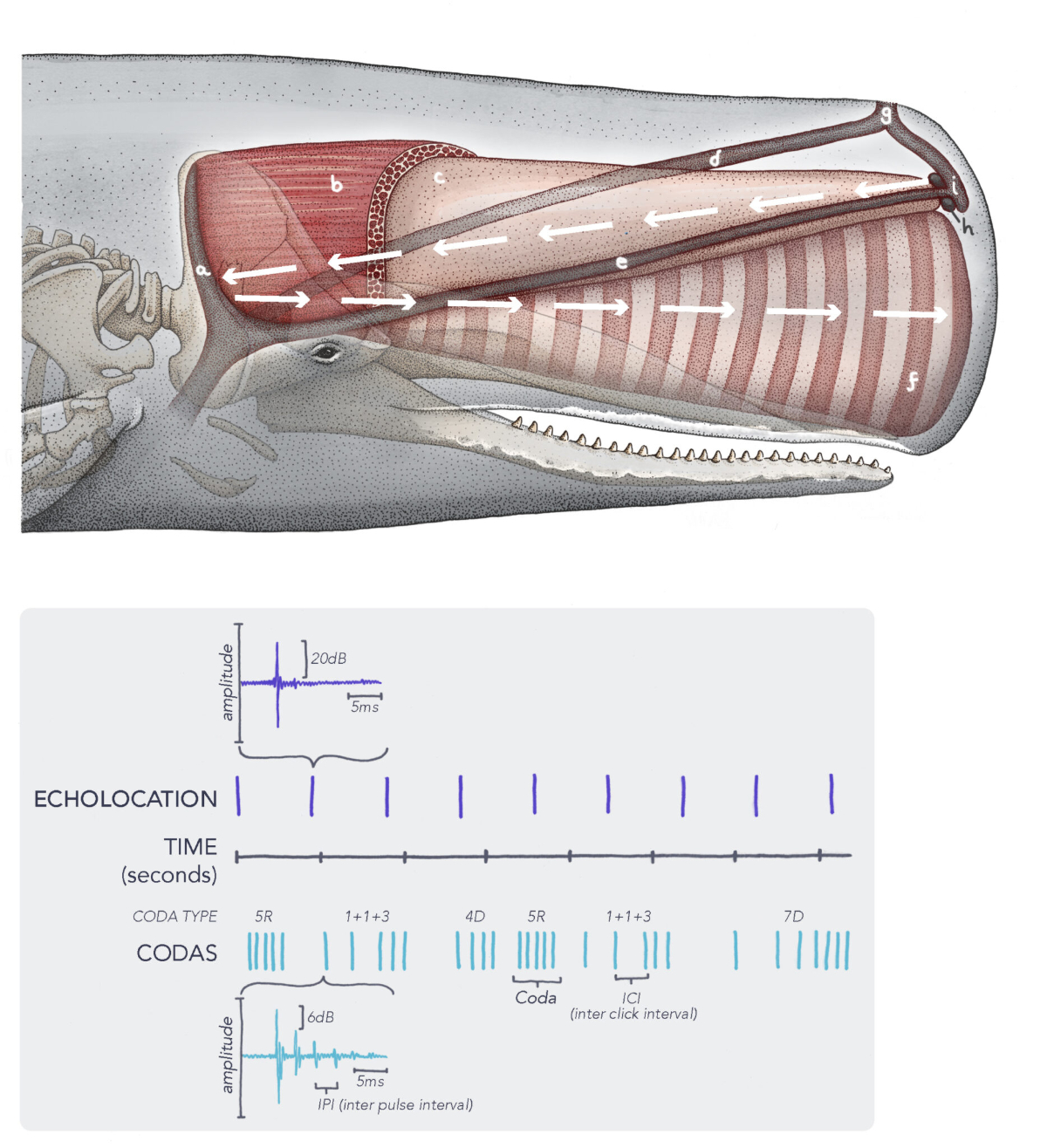

Using drones, on-whale sensors, and hydrophones, the CETI team records the communications known as codas from sperm whales. Their research suggests the animals, which have the largest brains of any species, produce rhythmic bursts of clicks by pushing air through their nasal passages and over the “phonic lips” in their heads. The recordings are then fed into custom-built computer models like ChatGPT for whales that help researchers identify patterns.

CETI has already analyzed thousands of codas, and discovered that sperm whales have an “alphabet” that imbues those sounds with conversational context and social meaning — a complexity of communication far greater than previously believed possible. The whales even have dialects. “Prior studies have shown that pods from different parts of the ocean vocalize as differently as a New Yorker and a Texan,” ICN says.

Some readers may see a connection between this discovery and a scene from Steven Spielberg’s Close Encounters, in which aliens communicate with earthlings using music.

The MOTH Program

The paper is co-authored by Gruber, Gašper Beguš, a linguistics expert, and César Rodríguez-Garavito and Ashley Otilia Nemeth, attorneys with the New York University Law School’s More Than Human Life (MOTH) program. Together they ask whether decoding whale communications could shift public apathy and usher in a “new, immense legal world”?

The inability — or refusal — of humans to recognize that other species are sentient and able to communicate with each other has led to suffering in ways that barely register with most people. Sperm whales and other cetaceans live in a world where sound replaces sight, where life depends on vibrations, and silence or noise can mean survival or death.

“In that world, human noise isn’t an irritant—it’s a form of violence,” ICN’s Katie Surma writes. “The constant roar of ship engines and seismic blasts from military sonar, deep sea mining and fossil fuel operations, inflict agony. Chronic exposure disorients whales, drives them from feeding grounds and floods their bodies with stress hormones. At higher intensities, the noise can cause internal bleeding and permanent hearing loss.”

The global shipping fleet continues to grow, with more than 100,000 ocean-going vessels plying the sea lanes. Ship strikes kill around 20,000 whales each year. Many of those boats carry oil and gas, products whose use has driven oceans to absorb a quarter of all greenhouse gas emissions and nearly 90 percent of the planet’s excess heat, acidifying waters, bleaching corals, and driving species toward extinction.

Listen To The Whales

Could all of this change if whales could tell us, in their own voices, the agony we inflict? Would we listen? Gruber and his co-authors think so. History shows that when science deepens our understanding of other beings’ inner lives, society’s laws eventually follow. The authors argue that the discovery of whale language could lead to the recognition of important legal rights for sperm whales, namely the right to be free from torture and the right to create and maintain a culture.

Until now, the primary way of knowing the impact of sound on whales was to observe their bloodied eardrums. “Now we can look at it through signatures in their voices,” Gruber says. A right to be free from torture would go far beyond today’s anti-cruelty laws, which are riddled with loopholes and, as the paper puts it, “fail to capture the panoply of covert physical and psychological harm.” It would also acknowledge something deeper — how closely human and whale suffering align.

Courts have applied the human right to be free from torture in cases of sensory overload or deprivation, such as blaring deafening music at detainees at Guantánamo Bay for days on end. For whales, Rodríguez-Garavito said, human noise is the “equivalent of shining a blinding light straight into a human’s eyes, which is a form of torture.”

Courts have also recognized torture in the anguish caused by separation from loved ones. The paper points to the case of a mother whale named Juno, a North Atlantic right whale who was forced to watch her child’s “slow, agonizing death” after being fatally gashed by the propeller of a ship. “All legal rights seemed radical once,” ICN says. “Before 1948, the human right to be free from torture did not exist.”

What Rights Do Animals Have?

The issue is whether we humans have an obligation to refrain from harming other animals who share the Earth with us. Should someone who swats a mosquito be prosecuted? Is using hooks to capture fish unnecessarily cruel? The legal ramifications of the work being done by CETI are far ranging. Ultimately, it comes down to whether we are entitled to disregard the suffering of animals caused by our activities?

ICN’s Surma writes that a decade before publishing “On the Origin of Species” in 1859, Charles Darwin confided to a friend that sharing his theory of evolution felt “like confessing a murder,” because his theory of evolution didn’t just upend the biblical belief that God made humans uniquely superior, it threatened the economic systems built on human domination over nature.

No doubt many would react in horror at the idea of whales having legal rights. Is a whale going to testify in court? The whole thing is ludicrous! Madness!! Or is it?

Sign up for CleanTechnica’s Weekly Substack for Zach and Scott’s in-depth analyses and high level summaries, sign up for our daily newsletter, and follow us on Google News!

Have a tip for CleanTechnica? Want to advertise? Want to suggest a guest for our CleanTech Talk podcast? Contact us here.

Sign up for our daily newsletter for 15 new cleantech stories a day. Or sign up for our weekly one on top stories of the week if daily is too frequent.

CleanTechnica uses affiliate links. See our policy here.

CleanTechnica’s Comment Policy