(Bloomberg) —

Buffeted by waves as high as 10 meters (32 feet) in China’s Yellow Sea about 30 kilometers off the coast of Shandong province, two circular rafts carrying neat rows of solar panels began generating electricity late last year, a crucial step toward a new breakthrough for clean energy.

The experiment by State Power Investment Corp., China’s biggest renewable power developer, and Norway-based developer Ocean Sun AS is one of the most high-profile tests yet of offshore solar technology. It’s a potential advance in the sector that would enable locations out at sea to host renewables, and help land-constrained regions accelerate a transition away from fossil fuels.

Most initial trials of solar-at-sea have involved small-scale systems, and there are numerous challenges still to overcome — including higher costs and the impacts of corrosive salts or destructive winds. Yet developers are increasingly confident that offshore solar can become a significant new segment in renewable energy.

“The application of this is virtually unlimited,” because many regions have constraints on the use of land, including parts of Europe, Africa and Asia along with locations like Singapore and Hong Kong, said Ocean Sun’s Chief Executive Officer Børge Bjørneklett. “In these places, you see there’s a huge interest for this technology.”

Shandong, the industrial hub south of Beijing, plans to add more than 11 gigawatts of solar offshore by 2025, and to ultimately build 42 gigawatts, more than the current power generation capacity of Norway. Neighboring Jiangsu has a target to add 12.7 gigawatts, while provinces like Fujian and Tianjin are also studying proposals. Japan, the Netherlands and Malaysia are among other nations conducting or preparing test projects.

Floating panels at the Canoe Brook water treatment plant in Short Hills, New Jersey. Photographer: Bing Guan/Bloomberg

Even with investments in solar forecast to surpass spending on oil production for the first time this year, many regions face challenges in finding land to install vast arrays of panels, either because of a lack of available space, as a result of inhospitable terrain, or because to do so would require deforestation.

That’s spurring the push to examine new, and sometimes unlikely, sites for solar that’s already seen hundreds of floating projects delivered on lakes, reservoirs, fish farms and dams. Japan has dozens of smaller arrays, China and India have added major operations, and facilities have been built in nations including Colombia, Israel and Ghana. In January, the largest floating solar project in the US was brought fully online, supplying enough power for 1,400 homes from panels at the Canoe Brook water treatment plant in New Jersey.

“Renewables installation must grow, but the realistic question is where to build,” said Li Xiang, head of the solar-on-water unit at Hefei, China-based Sungrow Power Supply Co., one of the world’s largest renewable energy equipment makers. “We think water surfaces have great potential.”

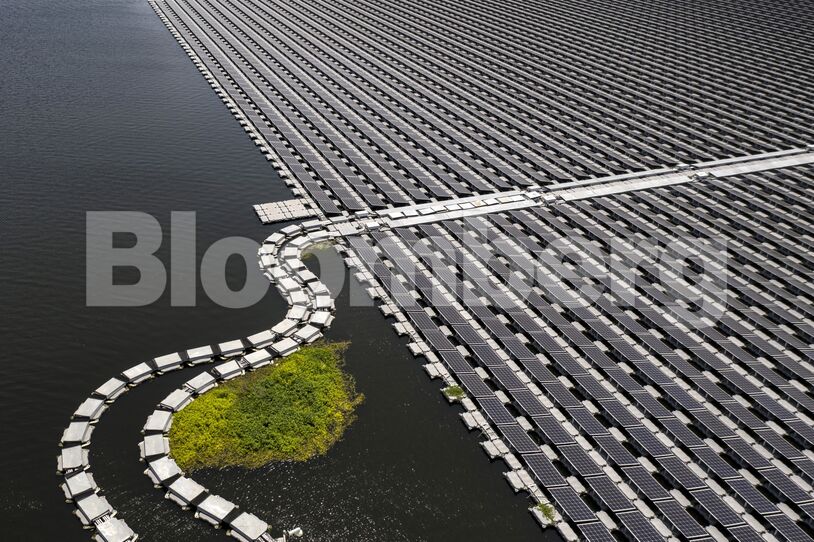

Stretched out across the dark green water of an artificial lake in Huainan, in China’s eastern Anhui province, is an installation of about half a million floating solar panels clustered into vast blocks, with white geese swimming by. The project built by Sungrow, on the site of a former coal mine since filled with water, covers the size of more than 400 soccer pitches and generates power for more than 100,000 homes.

A project of about half a million floating solar panels was built on the site of a former coal mine filled with water in Huainan, China. Photographer: Qilai Shen/Bloomberg

The installation covers the size of more than 400 soccer pitches and generates power for more than 100,000 homes. Photographer: Qilai Shen/Bloomberg

Adding solar systems on existing reservoirs could theoretically allow more than 6,000 global cities and communities to develop self-sufficient power systems, researchers including Zeng Zhenzhong, an associate professor at Southern University of Science and Technology in Shenzhen, said in a paper published in March. “We don’t need to fight for farmlands, nor do we need to cut forests or even go to the deserts,” Zeng said in an interview.

Yet more assessments are needed of the potential long-term consequences of covering water bodies with panels, the researchers found. China’s authorities have become wary too. New developments in some freshwater locations were banned last May amid concerns about the impacts on ecosystems and flood control. A solar installation in Jiangsu province that covered 70% of a lake’s surface was partially dismantled after local officials raised objections.

Floating solar panels on the Hapcheon Dam in Hapcheon, South Korea. Photographer: SeongJoon Cho/Bloomberg

While solar plants on freshwater sites are forecast to continue to expand globally, some of those concerns — and the potential of projects at sea — are helping to drive activity in the offshore sector. China’s Ministry of Science and Technology has made it a key priority to develop near-shore floating technologies by 2025, while companies such as Sungrow are among those collaborating with researchers.

Ocean-based solar arrays that can handle waves of up to four meters could be ready for commercial deployment within a year, and systems able to withstand 10-meter high swells will take at least three years to perfect, according to Ocean Sun. Viable technology could be ready within one to two years, according to Southern University’s Zeng, who is also studying offshore developments.

Developers are experimenting with differing concepts. Ocean Sun’s ring-shaped floaters, made of high-density plastic pipes and a membrane with panels laid out across the surface, undulate with the movement of waves. Rotterdam-based SolarDuck AS mounts panels on triangular platforms and has agreements to test its systems, including in Tokyo Bay and in a project off the coast of Tioman Island in Malaysia.

Workers prepare a floating solar farm for use at a reservoir in Alqueva, Portugal. Photographer: Goncalo Fonseca/Bloomberg

Questions remain about the ultimate scale of the offshore solar market. Developing panels at sea could be around 40% more expensive thanks to more complex installations and costly subsea cables, according to BloombergNEF estimates. Unlike offshore wind, which produces more power than onshore farms because of stronger gusts and larger turbines, there’s no major benefit to power generation in harvesting the sun’s rays at sea versus land.

“Offshore solar in some ways is the worst of both worlds,” said Cosimo Ries, an analyst with Trivium China. “You get the higher installation costs, but you don’t get the higher power output.” Solar-at-sea is likely to end up a niche sector, mostly serving land-starved coastal cities like Singapore, Ries said.

Advocates insist the technology is fast improving, and will win a role in helping nations with large populations and a lack of land to curb emissions and — for many developing economies — to meet still rising energy demand.

Longi Green Energy Technology Co., the world’s biggest producer of panels, is developing modules specifically suited for conditions at sea, and has a study underway in Jiangsu province. While it sees the market size as limited now, there’s “relatively large potential for offshore solar,” the company said in a March conference presentation in Xiamen.

Floating solar panels on the sea in Goheung, South Korea. Developing panels at sea could be around 40% more expensive thanks to more complex installations and costly subsea cables, according to BloombergNEF estimates. Photographer: SeongJoon Cho/Bloomberg

China alone has potential to host about 700 gigawatts of offshore solar — about as much as the combined electricity generation capacity of India and Japan — according to a State Power Investment forecast.

“It is not going to be difficult,” said Southern University’s Zeng. “People have not yet realized how much potential it has.”

Share This: