Sign up for daily news updates from CleanTechnica on email. Or follow us on Google News!

For three years, the International Chamber of Shipping has been running a survey of ship owners, covering multiple domains, including biggest risks to shipping, changes in shipping patterns with initiatives like friendshoring and most relevantly for this discussion, decarbonization. Recently they dropped their 2023-2024 survey, and the results indicate ongoing confusion among shipowners, as well as a lot of successful lobbying and some wishful thinking.

LNG as a shipping fuel is seeing declining support, one of the better notes from the results. For those not paying attention, burning methane in ship engines has been a big business for the past 20 years. In addition to the obvious use in LNG tankers, it’s taken the passenger ferry and cruise ship industries by storm, mostly because it doesn’t stink nearly as badly as legacy maritime shipping fuels when burned.

Unfortunately, the methane-burning advocacy groups have been challenged by it only providing 20% to 30% carbon dioxide emissions compared to heavy fuel oil, something that the shipowners acknowledge. However, even that’s an overstatement, as that’s in a better than best case scenario.

Well-to-tank is problematic, as the global natural gas and LNG supply chain is leaky as a sieve, especially in major exporting countries like the US, Russia and Qatar. While natural gas can be extracted, processed, stored and distributed with minimal fugitive emissions, only northern Europe has actually delivered on that promise by engineering in emissions-avoidance for the past few decades. As a result, upstream methane emissions are quite high, while advocates tend to promote northern European levels of emissions. Methane emissions, of course, are highly problematic due to methane’s high global warming potential.

Liquifying natural gas requires 8% to 12% of the embodied energy, so upstream fugitive emissions are increased by those percentages. And most liquification facilities burn natural gas to create the electricity for liquification, so more well to tank emissions. Then there’s boil off. Better operators reliquify excess boil off, but that means burning more LNG to power liquification.

And tank-to-wake isn’t nearly as clean as advertised either. The International Council on Clean Transportation ran a two-year monitoring exercise, Fugitive and Unburned Methane Emissions from Ships (FUMES), which involved using industry standard methane detection technology on smokestacks on the vessels in the study. While the industry was promoting only 3.5% methane slippage — the percentage of the fuel that was unburnt — the ICCT’s study found an average of 6.4%.

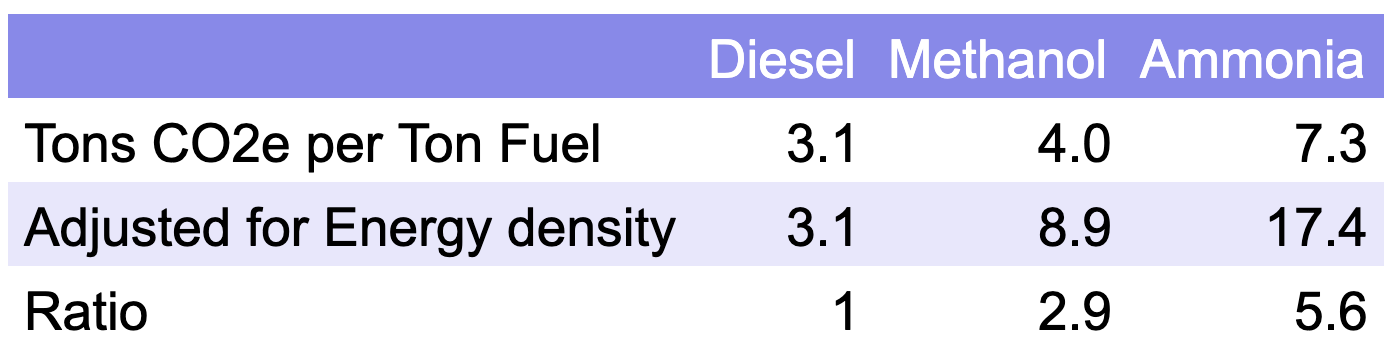

LNG is more energy dense by mass than heavy fuel oil and has less carbon in its makeup. Burning a ton of heavy fuel oil (HFO) emits 3.1 tons of carbon dioxide, and the equivalent energy of LNG only emits 2.3 tons, which seems like a win. But 6.4% slippage adds 1.6 tons of carbon dioxide equivalent (CO2e) to LNG’s emissions, bringing it up to 3.7 tons, well above HFO. That’s not a climate win.

The industry has been swayed by lifecycle carbon assessment’s like Sphera’s, which found 23% savings well-to-wake, but that’s not remotely realistic. What’s the provenance of that study? It was commissioned by two organizations, SEA-LNG and SGMF (Society for Gas as a Marine Fuel) which clearly found a willing consultancy to write a report that gave them the results they needed to promote their product.

Even the industry standard 3.5% slippage adds 0.08 tons of CO2e, meaning that the ‘good’ case is exactly the same as the HFO base case. That’s before you add well-to-tank emissions. This isn’t a climate win, it’s a distraction by the fossil fuel industry, hence the point about successful lobbying in the opening paragraph.

Ship operators like LNG because of it makes passengers happier and leads to fewer complaints from ports and the cities that surround them, so you can see why it’s taken off and why despite exactly zero climate benefit it remains the most highly rated alternative energy source for shipping for the next decade, at least among the 104 shipowners who responded in full to the survey.

Biofuels, an actual climate solution, have been slipping too. Unlike LNG, where the benefits are vaporware, the slippage is likely due to ongoing international confusion about what constitutes sustainably manufactured biodiesel. In a professional discussion this morning, we were shaking our heads over the EU’s legislated distaste for cropped biofuels like soy beans or canola while simultaneously considering cutting down virgin trees to pelletize for thermal energy and electricity to be carbon neutral.

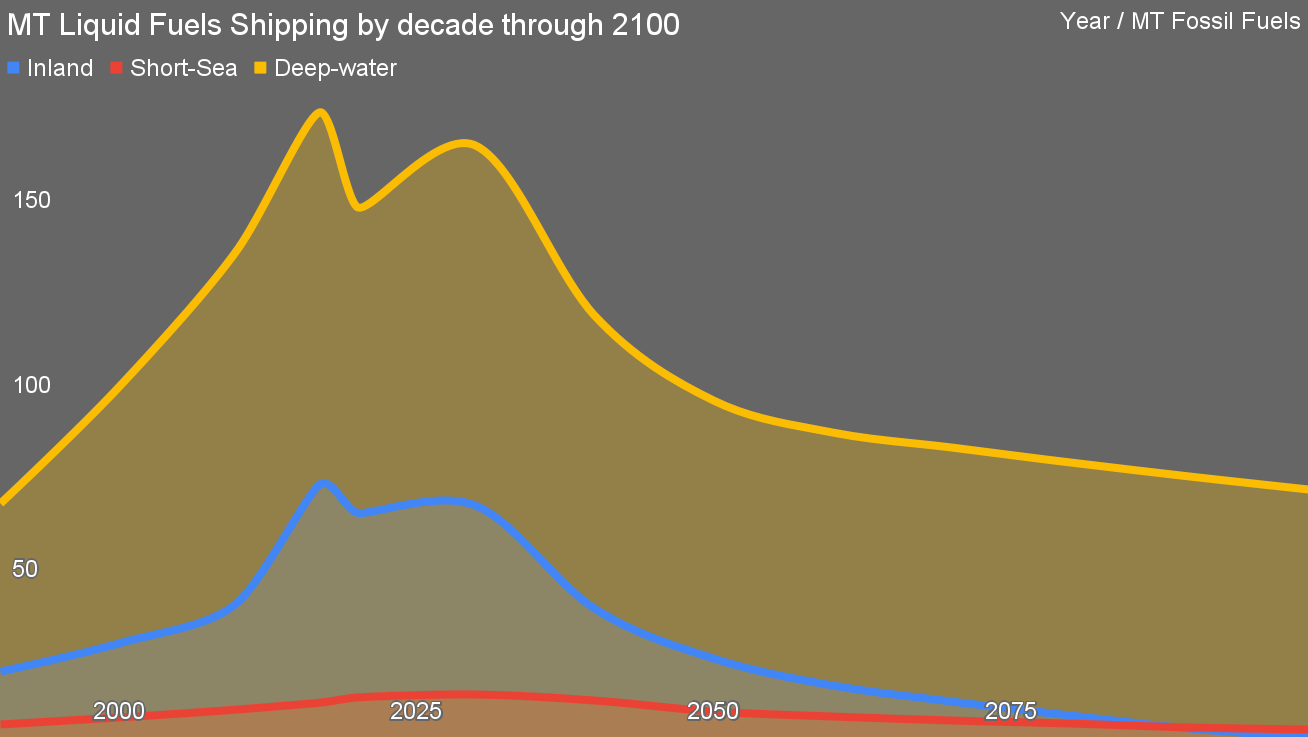

Jurisdictions in the USA like California are following down this silly pathway as well, based on a combination of factors. The first is the assumption that massively more biofuels than are currently manufactured would be required, which isn’t the case, but is very common. That’s based on an assumption of a continuation of ground transportation requiring fuels when globally it’s all going to electrify, with slower geographies like the USA, and an assumption of massive growth in shipping and aviation which aren’t supported by reality. In the case of shipping, 40% of bulks are coal, oil and gas and those are going to diminish radically in the coming decades, so shipping demand as a whole is going to plummet. Inland and short sea shipping is already electrifying, so that’s not a demand growth area, once again outside of the USA. Aviation growth is going to be much slower than IATA and Boeing insist and much more of it will electrify as well.

My projections require 180 million tons of biodiesel and biokerosene in 2100, 70 million for shipping, and the world is already manufacturing 70 million tons of biodiesel today per the IEA. But 500 million ton projections are rife, and people holding onto that belief will rightly say we can’t easily manufacture that much biofuel.

My position is based on an assessment of all of the pathways to biofuels, many of them from existing biomass waste streams we are landfilling today, including the 33% of all food, a full 2.5 billion tons, we landfill annually around the world.

Over 40% support for biofuels for shipping isn’t bad, in other words. It’s aligned with reality and it’s the problem of getting everyone to agree what actually is a sustainable biofuel that’s causing shipowners to question how much they’ll get this decade.

Methanol shooting up this year must be making the Methanol Institute’s lobbying hearts grow two sizes, or at least their year-end bonuses. That’s mostly due to a hangover, which is perhaps appropriate for an alcohol. Methanol is a tank-to-wake winner, much more so than LNG with it’s slippage. But well-to-tank sucks, and methanol’s current carbon intensity is almost three times worse than HFO.

For the past decade the methanol industry has been selling tank-to-wake and promising that well-to-wake would be cleaned up in the future and be cheap to boot. Yeah, not so fast.

Unfortunately, they developed a head of steam. Firms like one-time client Stena Sphere, which invited me to debate maritime decarbonization in Glasgow last year, started working on burning methanol on ships occasionally as proof of concept about a decade ago. Shipping giant Maersk believed the hype about cheap hydrogen and methanol being derivative of it, and they put in orders for dual-fuel methanol ships and even closed some green methanol deals. Those deals were mostly biomethanol, however, not hydrogen-derived methanol.

The combination of hard lobbying and Maersk led a few other shipping firms to put in orders for dual-fuel methanol ships. That’s led to a book of ships and that’s led to a bunch of shipowners thinking that there must be some there there if other shipowners are buying the sips.

As I keep saying, the nice thing about methanol dual fuel ships is that they’ll still be able to burn biodiesel, and further, that’s what they’ll be burning over the coming decades. The almost 40% support is because shipowners have no idea that getting agreed upon standards for sustainable methanol will be just as tough as as for biodiesel.

But as I also said to the Stena audience last year, if biologically sourced methanol becomes the low-carbon shipping fuel of choice, I won’t complain much. I’ll wonder why they chose a sub-optimal choice compared to batteries and biofuels, but I won’t lose sleep over it.

The fall of HFO with carbon capture is a good thing, but at almost 40%, shipping delusions that they’ll keep everything the same and put a cheap vacuum cleaner on their smokestacks are obviously persisting. This is a combination of psychology — a cheap technical fix and nothing else is a very appealing story — and heavy lobbying by the fossil fuel industry. As I said during my India utility professionals seminar the other week, Carbon Capture Is Mostly An Oil & Gas Industry Shell Game. That will continue to sink in as silly trials prove reality to yet again be reality and startups in the space founder.

Sadly, the experience with the Global Centre for Maritime Decarbonization’s ammonia bunkering trial makes it clear that that organization’s multi-million dollar efforts won’t provide the nail in the coffin for either ammonia or carbon capture on ships, being solely devoted to narrowly making the technology work without any published technoeconomics or, in the case of ammonia, any realistic risk publications. Thankfully, they are also working on biofuel provenance tracing, so some good will come of it.

The drop in hybrid power trains — fuels plus batteries or other faint hope energy storage systems — dropped. I suspect a bit of that is that energy storage systems that failed miserably to gain traction against batteries elsewhere have overhyped, oversold and failed, so there’s some jaundiced views. It’s hard to say why this is the case otherwise, as battery prices have continued to plummet every year, with prices of $137/kWh in 2020 dropping to $56 for LFP this year.

And a Berkeley National Laboratory study published in Nature Energy in 2022, Rapid battery cost declines accelerate the prospects of all-electric interregional container shipping, makes the strong case that at $100 per kWh, 1,500 km routes are break even for batteries. It’s not mass or volume, it’s cost, is the study’s conclusion, and battery breakevens are here even if the industry is molecule-centric.

Hybrid power trains are a big part of my projection for maritime decarbonization, at least for deep water shipping. I expect all national waters and port operations to be running on batteries, and an increasing proportion of international water movement. Batteries only will win out for inland and most short sea shipping.

But there’s lobbying at work here too. The amplification of the remarkably small number of lithium ion battery fires and the disinformation campaigns attributing internal combustion fires to electric vehicles has undoubtedly had an impact on shipowners as well. The fossil fuel industry realizes that they can’t even pivot to biofuels if batteries win, so they are fighting a propaganda campaign on multiple fronts.

However, a third of the respondents still rate hybrid models as strong contenders for the next decade, so there’s that.

Then we get into the cheap seats with limited support. That ammonia is still seeing 30% support is mind boggling. As the well-to-wake emissions show, for unabated ammonia emissions are 5.6 times worse than HFO. Tank-to-wake is awesome because ammonia doesn’t have any carbon at all, but that’s irrelevant because the stuff is an emissions bomb upstream. That’s going to be hard and — most importantly — expensive to abate, so ammonia will be priced out of the market.

And then there’s the danger to crews, port staff, the residents of cities around ports and marine life. Ammonia is nasty stuff, and while we do ship it globally because it’s an essential fertilizer, we treat it as a toxic and hazardous substance and only let specially trained port and shipping crews work with it in specially segregated portions of ports.

Ammonia isn’t going to get cheaper or safer, so that it can be made actually low carbon is irrelevant. That 30% of shipowners haven’t figured that out is pretty depressing. Perhaps they are the ones operating the 66 or so ammonia tankers running around the place and know they’ll never have to be near the ships or ports personally.

Then there’s nuclear. Hope springs eternal, but as I said last year, No, There Won’t Be Nuclear-Powered Commercial Shipping This Time Either. The entire overhyped idea of nuclear commercial shipping was tried in the 1950s and countries actually brought in laws prohibiting it. No commercial port has any safety or operational guidelines today for accepting a nuclear freight ship, and none are developing them. The owner-operator schism in terms of capital costs vs operating cost benefits isn’t irresolvable, but it’s a Gordian knot.

The entire concept depends on small modular reactors existing as commercialized products and scaled in terms of ground deployment to make them cheap enough for commercial ships. That’s just not going to happen in ten years, or even 40. Once again, as I said last year, Shoveling Money Into Small Modular Nuclear Reactors Won’t Make Their Electricity Cheap. Far too many designs competing for far too little deployment for any of them to benefit from the experience curve.

That nuclear has doubled in hoped for support as a viable alternative within the next ten years can only be ascribed to confusion about everything else on the part of shipowners. This is a case of throwing up their hands and praying for a miracle. No commercial freight ship powered by nuclear reactors exists, no one is building any, no port is willing to accept them, the economics don’t stack up, and yet 22% of shipowners think it’s a this-decade part of the solution? Clearly irrational thinking was setting in when they were answering about nuclear.

Hydrogen support plummeting from almost 30% to under 20% can only be considered a blessing as the scales of the hydrogen hype fall from maritime shipping professional’s eyes. Everyone that seriously works on cost models rapidly finds that it would be incredibly expensive compared to obvious solutions, but a lot of terrible cost models were put forward in the past decade by otherwise serious organizations.

While I called out the ICCT’s great FUMES study above, it’s worth remembering that they fell down on hydrogen. Back in the late 2010s, they decided for some reason of their own that hydrogen was essential to lots of different transportation modes, that it was too expensive and so the only solution was to find ways to pretend it was going to be really cheap. Some of their work had reasonable kernels of data and logic, but then they want off base from that quite badly. They asserted that truck stops in Europe would get electricity a lot cheaper to make hydrogen than to put in truck batteries, and came to the unsupportable conclusion that hydrogen would only cost 10% more per kilometer for energy than electricity as a result. They pretended that hydrogen was essential for aviation and would be cheap.

And, of course, they pretended that cryogenic hydrogen with deeply unrealistic hydrogen manufacturing costs and no distribution or liquification costs would be available for shipping. To be clear, they were far from alone in the delusion of cheap green hydrogen. Reports from otherwise credible organizations around the world were pretending that electricity, electrolyzers, hydrogen storage and hydrogen distribution would be vastly cheaper than any realistic, informed perspective would support. In this, they were mightily supported by the fossil fuel industry again, which can only win if the world tries to make hydrogen an energy carrier. Either real decarbonization, almost entirely through direct electrification and lots of renewables, would be deferred another decade, or governments would throw lots of money at the fossil fuel industry for carbon capture for blue hydrogen.

But the past couple of years of green hydrogen deals has put a stake through the vampiric belief in cheap green hydrogen. Boston Consulting Group published a gloomy piece late last year that found that the average deal was struck at a price of €9.45 per kilogram, and admitted that the ‘consensus’ — read shared delusion — of €3 per kg hydrogen in 2030 wasn’t realistic, and that €5 to €8 was the range organizations should be preparing for. The upper end of that range is really what they should expecting, and that’s just for manufacturing the stuff. Currently unabated hydrogen is delivered by pipeline in Germany for €6 to €8, and there is no way for green hydrogen to every be anywhere near that price delivered.

The shipping industry appears to have been paying attention. Owners’ belief that hydrogen would be a part of decarbonization this decade dropped from 27% to 18%. That’s just more evidence that reality is starting to break through the hydrogen hype machine, even if the best result would having been to nip the most recent iteration in the bud a decade ago.

Windpower being up slightly can be ascribed to a lot of press for a couple of tiny freight vessels. This is the availability bias, where having heard about something enough times that it was vaguely familiar, more of them answered as if it might be a reasonable alternative. Even the ICS doesn’t believe that, calling it “not a viable primary propulsion method for most commercial applications” in the report. In the tiny niches where it can be used, it will save some fuel. My money is still on autolaunching and autofurling bow-mounted parafoils as the primary solution that will be useful on some routes. Among other things, it won’t interfere with the cranes in container ports, unlike every other alternative.

Then there’s the real head scratcher, batteries. As noted above, battery prices have plummeted, LFP batteries don’t have even the statistically limited thermal runaway issues of lithium ion batteries and there’s increasing technoeconomic support for battery shipping. This year saw two 700 TEU electric container ships start plying 1,000 km routes on the Yangtze, as well as a fair amount of realization that containerized batteries used for grid storage could be winched on and off ships and charged in transshipment terminals.

Everything should be coming up roses for batteries, but clearly there are irrational headwinds in the space. That said, it is a question of the next decade, and no one is buying battery only ships for crossing the Atlantic yet. It’s absurd that shipowners currently think sails have more potential than batteries, but that’s where we are.

Then there’s liquid petroleum gas (LPG), LNG’s uglier, less lobbied for sibling. Support for it is quite reasonably sinking.

As noted, there’s a lot of confusion in the industry about what’s going to be powering their ships over coming decade. Lobbying by the fossil fuel industry has created a lot of that. A strong cognitive bias for molecules for energy is undoubtedly playing a part. Resistance to change is part of it. The failure of long-promoted solutions that turned out to not to be cheap, easy or even solutions has created fatigue. The difficulty of actually agreeing on things hasn’t helped. The International Maritime Organization only requiring well-to-wake lifecycle carbon assessments starting in 2021 didn’t help. Some of it, of course, is members of the maritime industry who depend upon continued confusion to prevent any requirement for change who are creating unnecessary conflict to that end as a tactic.

But it won’t really matter in the long run. What will be cheapest and most effective is batteries and biofuels, often in combinations. The lobbyists can’t change the basics of economics and science, and they can only make sensible people pretend otherwise for so long. This confusion will pass.

Have a tip for CleanTechnica? Want to advertise? Want to suggest a guest for our CleanTech Talk podcast? Contact us here.

Latest CleanTechnica.TV Videos

CleanTechnica uses affiliate links. See our policy here.

CleanTechnica’s Comment Policy