Despite criticisms of REDD+ projects and a decline in related carbon credit prices this year, offsets issued by the Kasigau Corridor REDD+ project in Kenya have consistently commanded a price premium in the voluntary carbon market.

Voluntary REDD+ credits aim to fight climate change by protecting forests. REDD stands for “Reducing Emissions from Deforestation and forest Degradation” and the + refers to the role of conservation, sustainable management of forests and enhancement of forest carbon stocks. The initiative was introduced by the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) in 2007 and finalized at the 2015 UN Climate Change Conference in Paris. Voluntary REDD+ Credits go towards site-based activities that do not involve deforestation and promote conservation and sustainability, particularly in developing nations.

The project, which is operated by the company Wildlife Works, injected income into the region just as shifting rain patterns began to make longstanding ways of life increasingly untenable. Participating landowners have in turn helped the project to expand.

Villages surrounding the project area also have also helped it earn a CCB Gold co-benefits designation from carbon registry Verra by joining in conservation and community development efforts that create incentives for wildlife protection, refraining from cutting wood in the project area for charcoal, and altering farming practices to both grow drought-resistant crops and manage soil more sustainably.

That CCB Gold status helps Kasigau’s credits sell above average market value, according to OPIS pricing data.

A portion of the revenue from credit sales is returned to the region. Wildlife Works pays 30% of gross revenue to participating landowners and provides half of its net profit to six surrounding communities.

Because of this agreement, the fate of the region is tied, at least in part, to the pricing trends of the voluntary carbon market, which can be volatile depending on macroeconomic conditions. Still, Kasigau’s credits have proven to be resilient.

Weakening REDD+ Prices

Voluntary carbon markets are facing a comparative dry spell after seeing strong demand over the last two years.

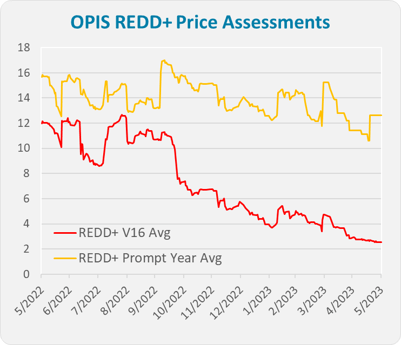

The OPIS Voluntary REDD+ Credits current-year vintage average price reached a high of $16.983/mt on Oct. 10, 2022, before falling by $6.358/mt to $10.625/mt on May 17, 2023. It rebounded to $12.625/mt on May 30.

The OPIS Voluntary REDD+ Credits current-year vintage average price reached a high of $16.983/mt on Oct. 10, 2022, before falling by $6.358/mt to $10.625/mt on May 17, 2023. It rebounded to $12.625/mt on May 30.

Part of the decline is tied to typical seasonal demand. Buying interest rose at the end of 2022 as corporations fulfilled annual decarbonization pledges then cooled off in the first quarter of 2023.

Meanwhile, rising interest rates and recession fears this year have taken a toll on voluntary carbon markets, sources said.

Public criticism of the United Nations’ Reducing Emissions from Deforestation and Forest Degradation, or REDD+ program, also had hurt prices. Earlier this year, a series of articles published by U.K. newspaper The Guardian said 90% of REDD+ rainforest carbon offsets registered by Verra “are worthless.”

In addition, the prices of voluntary carbon credits traded on standardized electronic markets, which are perceived to have less transparency in terms of project specifications and quality, have fallen sharply over the past six months.

The CME Nature-based Global Emissions Offset contract, which traded above $8/mt in the fourth-quarter of last year, has traded at times this month below $1/mt. Overall carbon credit volumes on Xpansiv CBL, a major electronic carbon offset trading platform, fell to 9 million mt in the first quarter from 24.3 million mt in Q4 and 46.9 million mt in Q1 2022.

At the same time, credits from established projects like the Kasigau Corridor, which can be independently verified and often carry co-benefit designations like CCB and CCB Gold from Verra, have held higher values.

Everland, a company that markets offsets issued by the Kasigau Corridor project and others, has over the past two years seen an average credit sales price of $16/mt over the past two years.

Everland CEO Gerald Prolman said the company sells some credits on a forward basis, which locks in prices over the term of the contract, and others on a spot basis, with prices fluctuating with the market.

This strategy has allowed Everland and Wildlife Works to reliably invest in the co-benefits that help the project command premiums.

Co-benefits refer to the positive effects REDD+ projects have on their regions in addition to carbon sequestration. Verra’s CCB designation recognizes benefits to climate, community and biodiversity. A project can earn a CCB designation for meeting certain criteria, or a CCB Gold designation for clearing an even higher bar.

OPIS on May 30, 2023, assessed the price premium of these co-benefits at $3.50/credit for CCB and $3.70/credit for CCB Gold. Everland’s $16/mt average includes the costs of its marketing services, but it still outperforms the market, even considering the co-benefit factor.

While many voluntary carbon market stakeholders understand co-benefits as secondary to avoiding carbon emissions, things are different in Taita Taveta County, home of the Kasigau Corridor project. Many community members participating in the project see carbon offsetting as a means to an end, while the co-benefits the project delivers have a direct impact on their day-to-day life.

Life Before REDD+

The economy in Taita Taveta is dictated by the rains. They tend to come twice in a 12-month period, but climate change has reduced their frequency and volume. When drought comes, it directly affects almost everyone.

Agriculture accounts for 95% of income in Taita Taveta and 80% of employment, according to a 2016 county risk assessment from the Ministry of Agriculture, Livestock and Fisheries. The region also is well-suited to raising livestock due to low incidents of disease.

Much of the soil in the farmland in Taita Taveta has degraded due to overtilling and erosion. Wildlife Works uses a portion of revenue from carbon offset sales to run workshops that help farmers return nutrients to their soil and improve crop yield. (See photo below.)

During a 2012 drought, which affected crop yields, fueled forest fires and increased human-wildlife conflicts, an estimated 87,000 of the county’s then roughly 300,000 residents faced famine and starvation, according to the ministry.

Increasingly severe droughts have affected the region in recent decades and the challenges they pose have risen as the population continues to grow at a rate of 19.7%, according to the latest census in 2019.

Increasingly severe droughts have affected the region in recent decades and the challenges they pose have risen as the population continues to grow at a rate of 19.7%, according to the latest census in 2019.

As of May, the past five rainy seasons have failed to allow for normal growing conditions.

In the event of a drought, the rural areas of the county have two last-ditch economic safety nets: cutting down trees to produce charcoal to sell for income and poaching game to eat or sell. One must work hard at either practice to earn a living. The average charcoaler earns between $68 and $160 per month, according to a working paper by World Agroforestry.

As drought cycles have increased, more and more people began to rely on poaching and charcoaling to survive.

Mgeno Ranch Director and Treasurer Ferdinand Mwangazi, whose business is one of 16 ranch companies that host the REDD+ project, witnessed the unfolding situation. “Before the carbon project, there was what we can call the indiscriminate destruction of trees in these ranches, indiscriminate poaching,” Mwangazi said.

The ranch companies had little ability to prevent others from coming onto their land to poach or charcoal. Many lost large swathes of their herds to drought and predators and struggled to feed and water the livestock that remained. To compensate, many took out loans or welcomed nomadic herdsmen to graze their cattle on their land for a fee.

While these measures provided much-needed income, they weren’t sustainable and further depleted landholders’ resources, sources said.

Wildlife Works first came on the scene in the late 1990s after CEO Mike Korchinsky visited the region during a vacation. The company first bought a parcel of land between the Tsavo East National Park and the Tsavo West National Park. Wildlife tends to move through the corridor between national parks in the search for food and water and human-wildlife conflicts continue to present a major challenge.

Wildlife Works created the Rukinga Wildlife Sanctuary on the land it purchased to provide migrating animals with a safe stopover point between protected parks. The business also attempted to establish sources of income from both tourism and from a textile factory it established. But revenues from these streams were unable to grow the business and it struggled until it began to earn additional income from carbon credit sales in 2011.

Once the REDD+ business model proved viable, Wildlife Works reached out to surrounding ranching businesses to scale up operations. Sixteen ranches agreed to sign on in exchange for a share of the proceeds.

Funding from carbon credit sales allowed the landholders to halt the land degradation. They were able to employ their own rangers to patrol their land, build paddocks to protect their herds, construct their own water infrastructure and diversify their businesses with other income streams, such as beekeeping, raising chickens and tourism. All the while, their forests started to

regenerate.

“Today, not everything is under control, but there has been a lot of improvement,” Mwangazi said. “When we stand on the hills and look at the forest from above, we see lots of green. The forest cover is very good.”

Local Carbon Economy in Practice

Wildlife Works dispenses revenue from carbon offset sales as follows:

A portion of gross revenue, usually around 10%, covers transaction fees and costs associated with maintaining registration with Verra. For the remaining 90%, one-third is divided among the landowners that host the project.

The next portion — which varies each year — covers Wildlife Works’ operating costs, including initiatives such as the ranger department, the textile factory, an eco-charcoal production facility that produces the fuel without cutting down trees and a greenhouse department that both runs a tree nursery and educates farmers on sustainable agriculture practices.

The remaining profit is split between Wildlife Works and the six villages in the project vicinity.

Community members use the proceeds to fund initiatives they deem important for their village.

Some common uses include funding education bursaries for young people (only primary education is provided free in Kenya and families must pay to send their children to secondary school and beyond), school facilities, supplies and refurbishments and communal water infrastructure.

Carbon offsets have funded more than 32,000 bursaries for secondary students in the area.

The secondary school in the village of Marungu, which is one of the six participating communities, has received significant support from the project. Each of the 325 students attending the school receive an education bursary funded by the sale of carbon offsets.

Wildlife Works also provides the school with food for one meal a day. During periods of drought, the food students eat at school may be their only meal.” In the past we’ve had a lot of issues educating children,” said Deputy Principal David Mombo, who grew up in the region. “One reason is the elephants. When farmers plant maize and other crops, elephants often destroy them. So, many times, families don’t have food to eat. Kids come to school hungry,” Mombo said.

Still, Wildlife Works has not engineered a utopia.

The majority of carbon offset revenue available to the community flows to landholders, who have their own interests in protecting their land and whose goals, in practice, are largely aligned with the REDD+ methodology.

Of the 16 ranches that host the REDD+ project, some are individually owned, others are owned by private companies with fewer than 50 shareholders and still others are collective businesses composed of hundreds or thousands of families with smaller holdings. Private land tenure has a long, troubled history in Kenya, beginning with colonization in the 1890s.

Comparatively less income finds its way to neighboring villages, whose residents must forgo venturing onto others’ land to poach and cut down trees to make charcoal. Though these practices are destructive or illegal, they have provided a last-ditch source of income in times of need for past generations.

Still, the Kasigau Corridor REDD+ project brings income to the region from a source that, unlike agriculture, does not depend on drought cycle. Without that income, the region would be further exposed to the worsening effects of climate change.

Eric Sagwe works as the head ranger at Wildlife Works. His department, which employs more than 160 rangers and others, is responsible for patrolling the 500,000-acre project area to ensure no one poaches game, cuts down trees to produce charcoal or building materials or conducts other activities that could compromise the Kasigau project. While the role appointed to his department is challenging, their jobs would not exist without the REDD+ effort.

“The project is huge,” Sagwe said. “All of our teams have to go the extra mile just to cover each region. If there weren’t carbon credits … I don’t know … I don’t know.”

–Reporting and photography by Henry Kronk, hkronk@opisnet.com; Editing by Kylee West,

kwest@opisnet.com, Bridget Hunsucker, bhunsucker@opisnet.com and Jeff Barber,

jbarber@opisnet.com