Sign up for daily news updates from CleanTechnica on email. Or follow us on Google News!

The good news: oil demand is cooling. The bad news: it’s not yet done growing. One can’t really claim oil demand is “falling” (yet), but growth has slowed down to its lowest level in over a decade, with 2024 being a pivotal year. Let’s look at the realities of oil demand and its future from a cleantech perspective!

Where we’re standing

Before we start, it’s worth presenting a few numbers to get our readers up to date.

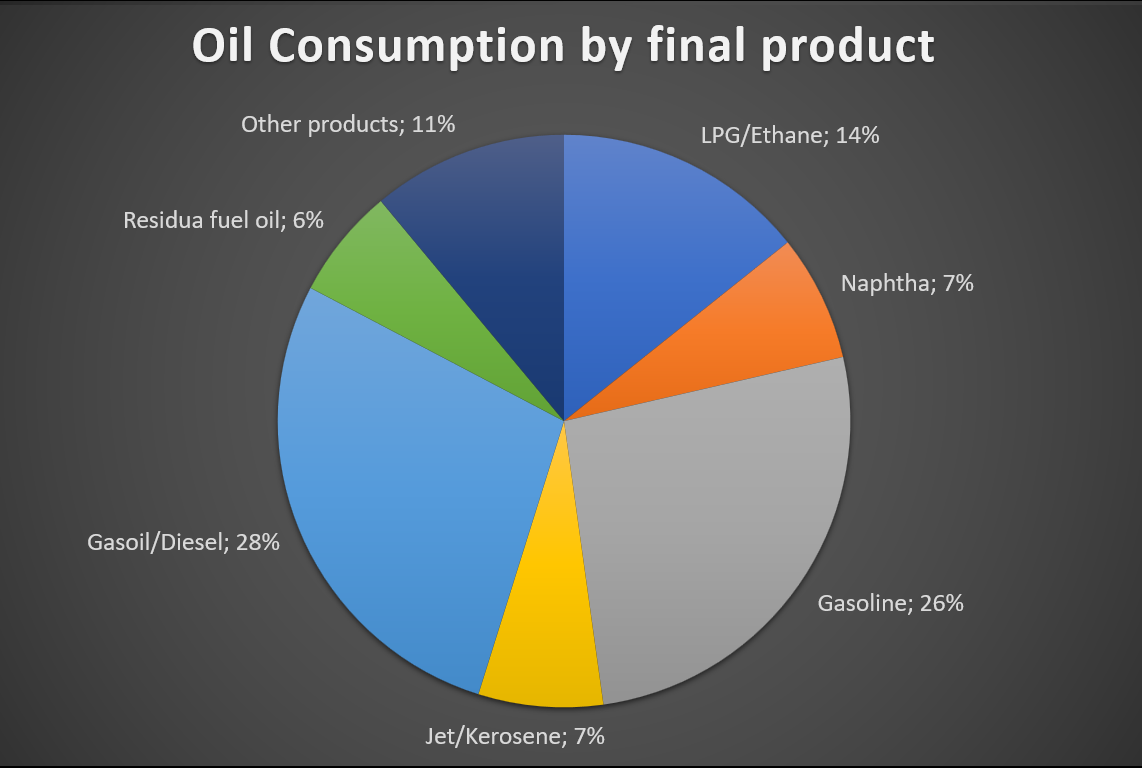

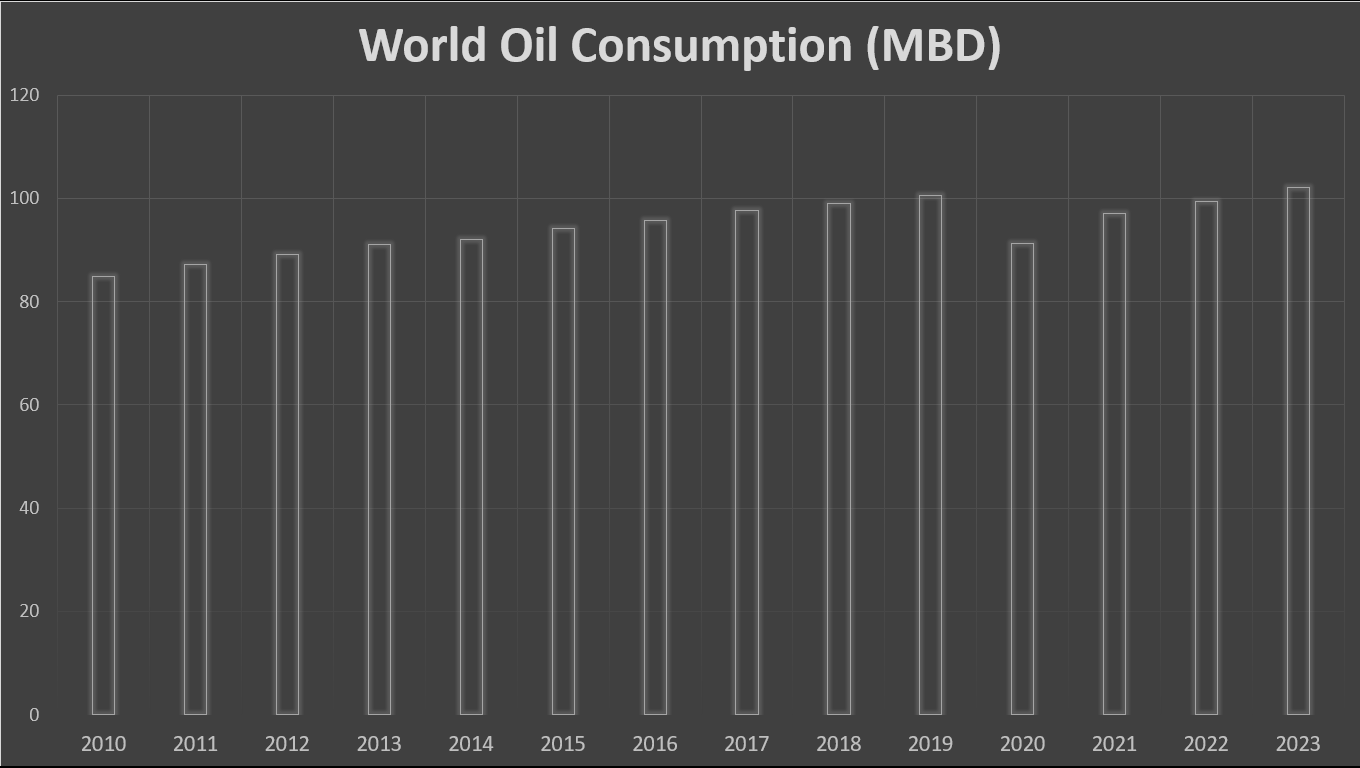

Oil consumption can be measured in many ways, but my favorite one is million barrels per day consumption, or mbd. Nowadays, world oil consumption clocks in at just above 100 mbd (102.1 mbd in 2023): around two-thirds of that are burned to move things around, with the rest being used for Liquefied Petroleum Gas (LPG, 14%), Naphtha (7%) and other products (11%), of which around 6% are plastics.

It wasn’t always this high. Back in 2010, oil demand was 16% less than today: 84.8 mbd. But the 2010’s were a golden decade for oil, with over 1.5 mbd yearly increases (half of this demand coming from China), getting to 100.6 mbd consumption in 2019. The pandemic brought that down to 91 mbd in 2020, but consumption recovered fast, and the record from 2019 was once again broken in 2023:

For those of us who care about the climate crisis, this is bad news. But in 2024, finally, things started to change.

You see, after the pandemic, oil demand recovered faster than many expected (or hoped), at levels even higher than those from the golden 2010’s. But by late 2023, a schism started to appear between the two largest institutions forecasting oil demand: the European IEA, and the organization of oil exporting countries, OPEC.

In early 2024, the IEA was forecasting an increase in oil demand for that year of “only” 1.2 mbd, below the 2010’s average. OPEC, meanwhile, was expecting the good times to continue (for them), with demand to grow 2.3 mbd. Such a stark difference had not been seen in over a decade, and it made for a lot of headlines.

Allow me to spoil the end: it seems, for now, that the IEA was right and OPEC was wrong. And it seems 2024 marked the turning point between a booming oil market, and a languid one that’s likely to end its growth in the foreseeable future.

2024: the year that bucked the trend

It started early. China had driven oil demand growth for years, but its economy was not growing as fast as it once had: amidst a severe building crisis, diesel consumption was far below what had been expected just a few months prior. Already in late 2023, weak demand and booming oil production in the US forced OPEC+ to suspend its planned increases (OPEC+ regularly produces less than it could in order to prop up prices, and nowadays some 5 mbd are being kept out of production by the organization).

Back then, I was already wondering why nobody was mentioning EVs as a factor. As nearly half of the cars sold in China had a plug, it seemed naive to blame oil demand woes on the building sector alone. But hey, probably these seasoned analysts knew more than I did, right?

As months passed, OPEC insisted that oil demand would recover in the second half of the year. Though, it was forced yet again in March to postpone its planned production increases. But the veil was yet to fall, and most analysts insisted this was a temporary consequence of the crisis in China.

It all started changing around mid-year. OPEC’s forecast (2.3 mbd demand growth in 2024) had remained unchanged, but as the first half of the year saw tepid growth year on year (<1 mbd in Q1, <0.8 mbd in Q2), it was becoming more and more clear that oil demand would need to basically explode in the second half of the year for this forecast to become a reality. Meanwhile, several factors started questioning the narratives from OPEC and Big Oil: EV sales exploded in China, bringing the “EV falling demand” narrative to an end; Chinese independent refineries greatly reduced their operations; and significant disruptions in the Middle East (which normally would’ve caused oil prices to spike) had little effect on price, indicating a market confident on oil abundance. Slowly but surely the narrative started to change as the realization set in: China’s oil demand woes were not a temporary issue, but a structural change. They were here to stay.

As of September, China has had 6 continuous months of falling oil consumption (year on year), making it clear that the country will no longer drive appetite for the fuel. Even worse for oil: when the country finally reacted to the economic crisis, one of the main investments was in a “cash-for-clunkers” scheme designed to get ICEVs off the road and replace them — mostly — with EVs, further destroying gasoline demand.

As reality set in, OPEC once again postponed its oil production increases, now set for January 2025: this is 16 months later than originally planned, and it’s almost certain they will be postponed again. After insisting for the first half of the year that oil demand would recover in the second half, the organization also had to lower its growth forecasts by 500,000 barrels a day. Even then, they remain at an increasingly implausible 1.8 mbd. Meanwhile, the IEA has not been blind to the winds blowing, and it has lowered its own growth forecast to a more realistic 920,000 barrels a day. Though, the exact number will only be known in 2025.

Yet, OPEC remains stubborn. They have now realized that China is a lost cause, but they hope for the rest of the developing world (and India in particular) to replace her. But as an analyst put it recently: the risk for OPEC (and Big Oil) is that China starts exporting its low appetite for oil in the form of cheap EVs and solar panels … and as we’ve seen in the booming markets of the developing world, this is exactly what’s happening.

Which brings us to the last part of our analysis: what comes next?

Scenario 1: A world where affordable oil is abundant

Oil is abundant, but it’s getting increasingly harder to access. This is a scenario where there are still massive reserves available all over the world for an extraction cost below, say, $30 (a number which would theoretically allow for oil to fall to $40 without bankrupting producers). Of course, this scenario is hypothetical.

Nowadays, oil demand keeps growing despite EVs for a number of reasons. First, the developing world remains increasingly hungry for energy and, as oil prices stay relatively low, consumption does increase to some degree. Second, some sectors, like petrochemicals or jet fuel, are unlikely to be replaced in the short term, further propping up demand. What we have here is a scenario where gasoline and diesel demand will fall, being partially offset by LPG, jet fuel, and petrochemicals.

As a side note, here at CleanTechnica, Michael Barnard has said that aviation will not grow to pre-pandemic levels of demand, but that’s something I find hard to believe, as tourism is a growing industry in the Global South. I agree with most of Michael’s analysis on most matters, but this one I’m still doubtful about: jet fuel consumption is yet to recover to pre-pandemic levels, but I think it’s only a matter of time.

Back to the matter at hand, even if demand for LPG or jet fuel rises, it’s likely that many analysts are underestimating the rate at which gasoline and diesel demand will diminish. As Zach said a few days ago, developing countries will leapfrog ICEVs and jump into EVs at faster rates than most people expect, and that includes India. The IEA, for example, calculates that gasoline consumption will reduce by a mere ~1.8 mbd by 2030, and that’s considered “optimistic” by many analysts … but I think it’s severely underestimating the impact from EVs.

If you remember our rough calculations from last year, we can assert that every 100 million EVs sold displace some 2 mbd consumption. It’s reasonable to forecast that 100 million EVs will be sold in 2024–2027 and then another 100 million in 2028–2030, which means the impact will easily reach 4 mbd by then, well above the IEA “optimistic” scenario.

The issue here is that the abundance of cheap oil coming from US shale, Brazil, Guyana, and other non-OPEC producers (who are not bound by OPEC’s cuts), paired with tepid demand, will mean prices get lower in the medium term, bringing them closer to the marginal cost of extracting oil, and somewhat promote its consumption, particularly in less developed economies … and the US.

Even with cheap gas, ICEVs are still more expensive to fuel and maintain than EVs, but the pressure to switch is much reduced with a gallon of gasoline at $2 or less. This would make the transition more dependent on political will, and, if that fails, it means demand could keep growing for a while or plateau for a few years.

So, in a world with abundant oil, we would expect tepid demand to bring lower prices, which will undoubtedly harm the transition, but should not matter so much in the long term as clean technologies take over more and more sectors of the economy. But climate change is already making a mess, so this is not a positive scenario: we would be dependent on political will to phase out fossil fuels, and that’s something sadly lacking in several countries, including the US with its new administration.

Scenario 2: A world where affordable oil is scarce

Brazil’s new discoveries are defined as ultra deep oil. US shale producers have been showing diminishing returns for a while, as these oilfields reach peak production much sooner than the traditional ones. Venezuela’s vast reserves are mainly extra-heavy crude in the Orinoco Belt, which would make it expensive to develop it even if the country wasn’t led by Maduro. With many oilfields around the world reaching maturity, it’s possible that the only region with vast and easily accessible reserves is the Middle East, but we know they’re willing to restrict production if that means higher profits, so don’t count on them to make oil cheap.

In this scenario, the same story plays out, with falling oil prices as tepid demand means the market is oversupplied as early as 2025. But that’s where the similarities end: as prices get lower, investment will fall, and more expensive fields will struggle. Oil production will inevitably falter, and at this point, its prices could become unstable, fluctuating dramatically whenever demand outpaces supply, and vice versa.

This instability, paired with the likely reluctance to invest money in expensive oilfields that could well be unprofitable a few years down the road, will make prices trend higher in the medium trend (and give more power to OPEC+ as far as the oil market is concerned). But, as nobody likes high prices and instability, in this scenario it’s likely many more countries will promote clean technologies to rid themselves of this pesky expense. In the previous scenario, I forecasted 200 million EV sales by the end of 2030, but that could easily turn into 300 million or more if oil prices get high enough.

If oil is scarce, and the only reason we’re producing as much of it is because of very high (and growing) demand, the inevitable reduction will wreak havoc on oil producers and it’s likely to accelerate the phaseout of fossil fuels: in this scenario, political will to fight climate change will not be required to make a swift and effective transition.

Final thoughts

I only superficially mentioned the newly elected US president, Donald Trump: it’s a given that his policies will favor fossil fuels, but the results are yet to be seen, and a sliver of hope endures. For one, US oil and gas production is already facing capital restraint, as companies consolidate and prioritize profits over investment. For another, if Trump does get his way with tariffs, the result could lead to lower consumption overall, bringing oil demand down by as much as 500,000 barrels a day. Both of these claims were made by oil-related media, so I don’t think they’re trying to greenwash Trump’s actions … I think they’re genuinely worried.

Trump is likely to hurt EV adoption in the short term in the US, but I hope the technology is mature enough that it will not make as much of a difference (and we’re yet to see what happens with Musk and Tesla). As for the rest of the developed world, they may not adopt EVs as fast as China and some developing countries, but the trend is clear by now and oil demand has little hope of growing in mature economies, with OECD demand expected to fall.

New technologies are coming, and they could work in both directions. US shale oil producers seem to become more efficient by the month, so even if oil is expensive today, it may not be tomorrow. But, just like that, it may well be that biofuels and batteries reduce jet fuel demand sooner than anticipated (so Michael may yet be right about this). For now, the highest impact is likely to come from EVs: expect diesel to suffer a significant hit (as gasoline already does) as soon as big electric trucks enter the scene en masse.

Fundamentally, what we’re seeing is a de-coupling between oil demand and economic growth, driven by the electrification of transport and renewable energy generation: this process marked the second half of 2024 and will continue to press oil demand in the future. OPEC’s and Big Oil’s hopes are placed on higher energy demand overall, and the fast-growing economies in the developing world.

But they will soon see these hopes are misplaced.

Have a tip for CleanTechnica? Want to advertise? Want to suggest a guest for our CleanTech Talk podcast? Contact us here.

Sign up for our daily newsletter for 15 new cleantech stories a day. Or sign up for our weekly one if daily is too frequent.

CleanTechnica uses affiliate links. See our policy here.

CleanTechnica’s Comment Policy