Support CleanTechnica’s work through a Substack subscription or on Stripe.

Pakistan’s request that Qatar divert or sell 24 contracted LNG cargoes in 2026 is a sharp signal for every country that still assumes LNG demand will rise for decades. Pakistan committed to long-term LNG contracts when its planners believed power demand would grow steadily and imported gas would fill the gap between domestic gas decline and rising consumption.

The country is now dealing with a different reality. Pakistan added roughly 17 GW of solar in 2024, which I wrote at the time was one of the most dramatic single-year shifts in any emerging market power system. The scale of that buildout changed Pakistan’s electricity mix in ways that planners had not expected. Solar pushed down daytime gas generation, reduced the number of hours gas generation plants operated, and exposed long-term LNG contracts to financial stress. The country’s rapid move toward low-cost domestic renewables was not driven by climate policy. It was driven by affordability, energy security, and the need to escape price volatility. The decision to offload two dozen LNG cargoes is consistent with the direction set in that earlier analysis.

Grid-scale batteries are emerging. Hydropower varies but can drop LNG use when water is available. Gas-fired plants are running fewer hours. Pakistan does not need the LNG it promised to buy and is trying to hand the cargoes back before they become financial liabilities. This is not a quirk of one stressed economy. It is the first visible failure of a demand model that assumes Asia will absorb LNG far into the future. Canada is preparing to become a major LNG exporter at the same time the pillars of that demand model are weakening. The question now is what this means for Canadian LNG megaprojects that are entering a market which looks less stable by the month.

The core driver behind the drop in LNG demand is the rapid global buildout of solar and battery storage. These two technologies cut into the role of gas in electricity systems. Combined cycle gas turbines used to provide steady baseload operation. Open cycle turbines filled the peaks. Solar cuts the daytime peak of the load curve and makes midday gas generation uncompetitive. Batteries fill up during the duck curve, provide part of the evening peak and are expanding their operating windows. Gas moves from being a backbone of the power system to being a less and less used peaking fuel. This changes the way LNG fits into national energy plans. In countries with LNG import contracts, the fixed cost of LNG becomes a burden when plants run fewer hours. The economics change quickly and governments begin looking for ways to reduce exposure. Canada is building LNG export infrastructure for a world that is using more renewable electricity and less imported gas. That disconnect is becoming clearer every quarter.

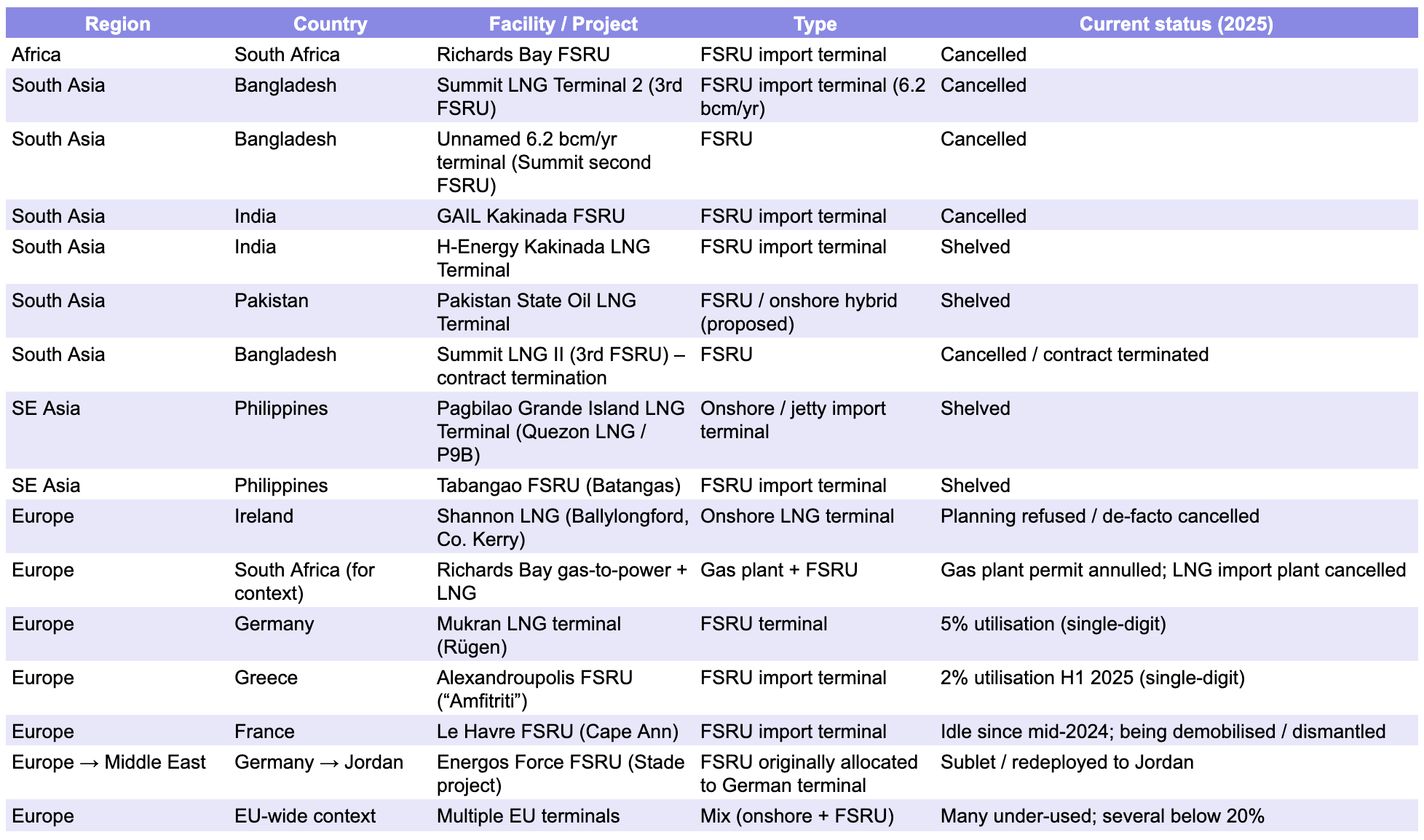

One way to see this shift is to look at the number of LNG import terminals that have been cancelled, paused or abandoned. As the table above, quickly assembled by me when considering this, and hence potentially containing inaccuracies, shows these terminals represent future demand that was expected to justify new LNG export megaprojects. It’s only 1% to 5%, depending on how you count it, of global LNG import facilities, but for exporters projecting a growth market, that contraction is significant.

In South Asia, Pakistan’s planned terminals have stalled. Bangladesh cancelled its third floating storage and regasification unit (FSRU) and halted expansion efforts. Sri Lanka cancelled an LNG project backed by Japanese partners. India shelved multiple coastal LNG terminals, including both Kakinada projects. The pattern is similar in Southeast Asia. Vietnam suspended or shelved much of its LNG terminal pipeline after adopting a long term power plan that shifted toward solar, wind and storage. The Philippines approved several LNG terminals but only one is operational and the rest lack financing, customers or construction momentum. Thailand has scaled back expansion plans after seeing gas demand flatten. These cancelled terminals represent the markets Canada expected to serve. The infrastructure is not being built because demand is not strong enough to support it.

The declines in LNG demand are sharper when looking at the major Asian economies. China’s LNG imports fell by about 22% in the first half of 2025. The country added more solar in a single year than the world added only a few years earlier. Large scale battery storage is expanding. Domestic gas production and pipeline gas from Central Asia and Russia reduce the need for imported LNG. When hydro output is high and solar grows quickly, LNG imports fall. China has re exported cargoes instead of consuming them. China is a significant buyer in some years and a marginal buyer in others. This variability undermines the old assumption that China would steadily increase LNG consumption.

India shows the same trend. India’s LNG imports fell by about 9% in the first part of 2025 on the back of a 34% decline in gas generation. Solar buildout is accelerating. Monsoon seasons boost hydropower and reduce gas plant output. Price sensitive industrial users shift away from LNG when spot prices rise. India recently resold a US LNG cargo to Europe because domestic demand was not high enough to justify taking delivery. Together China and India were expected to anchor the next twenty years of LNG demand. They are now building electricity systems that integrate solar, wind, hydro and batteries with much less dependence on imported gas.

Japan provides another important signal. Japan’s LNG imports have dropped as nuclear reactors restart and renewable electricity expands. Energy efficiency has improved, reducing total demand. Japanese utilities have shifted from consuming LNG to reselling it. They use flexible contracts to buy cargoes and then sell them on global markets when domestic demand is low. Long term LNG contracts used to anchor the global market. Japan was the stable buyer that made LNG export projects bankable. That role is disappearing as Japan reduces consumption and becomes a more flexible participant in LNG trading.

Europe has added another pressure point. Several European LNG import terminals are running at single digit utilisation. Germany’s Mukran terminal operated near 5% in the first quarter of 2025. Greece’s Alexandroupolis FSRU operated at roughly 2% during its early period due to a technical failure and weak demand. France’s Le Havre FSRU has been mostly idle and is being removed. Other European LNG terminals operate well below capacity. European gas demand has fallen due to steady renewable growth, more heat pumps and weaker industrial load. The LNG capacity built in response to the 2022 energy crisis is far more than Europe currently needs. This underuse adds more available LNG to global markets and increases competition for the remaining demand in Asia.

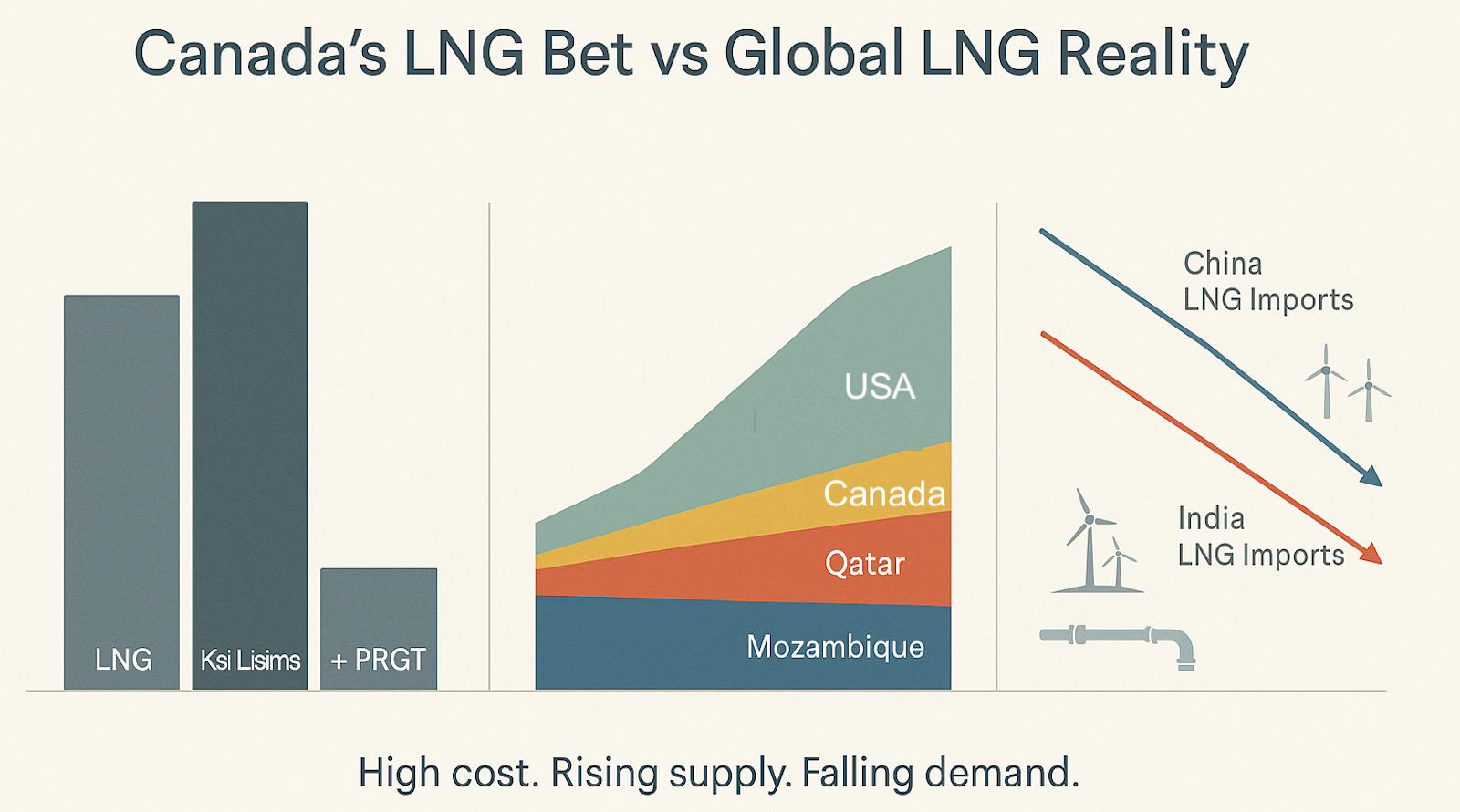

These demand reductions arrive at the same time that global LNG supply is expanding. Qatar is adding major new capacity from the North Field expansion. The United States is bringing a large wave of new liquefaction capacity online between 2025 and 2028. Papua LNG, Mozambique and other projects are emerging. Canada’s LNG Canada facility is entering service and other export proposals are in various stages of planning and review. The supply curve is rising while demand is flattening. Oversupply is inevitable. Prices will remain under pressure. Long term contracts will be harder to secure without concessions on flexibility and pricing. The large LNG supply wave is arriving just as the renewable energy buildout in Asia and Europe is reducing the number of hours gas plants operate. This is a structural mismatch that exporters will find hard to manage.

Canada’s LNG export strategy was built around the idea that Asian buyers would need more LNG for decades. That expectation shaped the development of LNG Canada in Kitimat and the next wave of proposed facilities that are part of national planning. LNG Canada alone locks in large emissions if it operates at full output for decades. As I noted recently, its total emissions could reach more than two billion tons of CO₂ equivalent over a fifty year lifespan. You have also written about the local impacts in Kitimat, including flaring and air quality issues. The project is positioned as both a nation building effort and an export engine. The difficulty is that it depends on global LNG demand that no longer looks stable.

The next wave of Canadian LNG faces an even tougher market. Many of the potential buyers that Canada targeted are cancelling import terminals, reducing LNG demand or reselling cargoes. Japan is not a reliable sink for LNG. China and India are reducing imports. South and Southeast Asia are not scaling LNG to the degree expected. Europe is oversupplied and is working to reduce gas consumption over the long term. That leaves Canada competing in a crowded market with Qatar, the United States and other low cost producers. Canada’s LNG production costs are higher than many of its competitors. If global demand remains weak Canada could become a swing producer that adjusts supply to balance the market. That would mean lower utilisation of export terminals and upstream assets.

The Canadian government is trying to balance LNG export expansion with climate targets. The contradiction is clear. If global LNG demand grows enough to support Canadian exports then global emissions outcomes are incompatible with stated climate goals. If global LNG demand stays flat or declines enough to meet climate targets then Canadian LNG facilities face a high risk of low utilisation or stranded asset outcomes. The result is a set of projects that struggle to align with both economic and climate objectives. The more solar and storage spreads across Asia the more these contradictions come into focus.

Pakistan’s twenty four LNG cargoes are an early marker of a broader trend. LNG demand is weakening across major consuming regions. Import infrastructure is being cancelled. Some import terminals that were built only a short time ago are running at very low utilisation. China and India have posted double digit drops in LNG imports in the first half of 2025. Japan is reselling LNG. Europe is overcapacity. Canada is entering the LNG export market during a period when renewable technologies are eroding the role of gas in electricity systems. The LNG market is changing faster than Canada’s planning cycle.

Sign up for CleanTechnica’s Weekly Substack for Zach and Scott’s in-depth analyses and high level summaries, sign up for our daily newsletter, and follow us on Google News!

Have a tip for CleanTechnica? Want to advertise? Want to suggest a guest for our CleanTech Talk podcast? Contact us here.

Sign up for our daily newsletter for 15 new cleantech stories a day. Or sign up for our weekly one on top stories of the week if daily is too frequent.

CleanTechnica uses affiliate links. See our policy here.

CleanTechnica’s Comment Policy