Sign up for daily news updates from CleanTechnica on email. Or follow us on Google News!

Recently I published on the International Maritime Organization’s commitment to introduce carbon pricing for all maritime shipping in 2028. One of the comments echoed something I’d seen elsewhere, the odd premise that this would drive freight to much higher emissions airplanes, and hence be counterproductive from a climate perspective.

The theory is that aviation will resist carbon pricing, which is completely true, and hence there will be a cost advantage for shipping by airplane. If true — it’s not — this would be a significant concern.

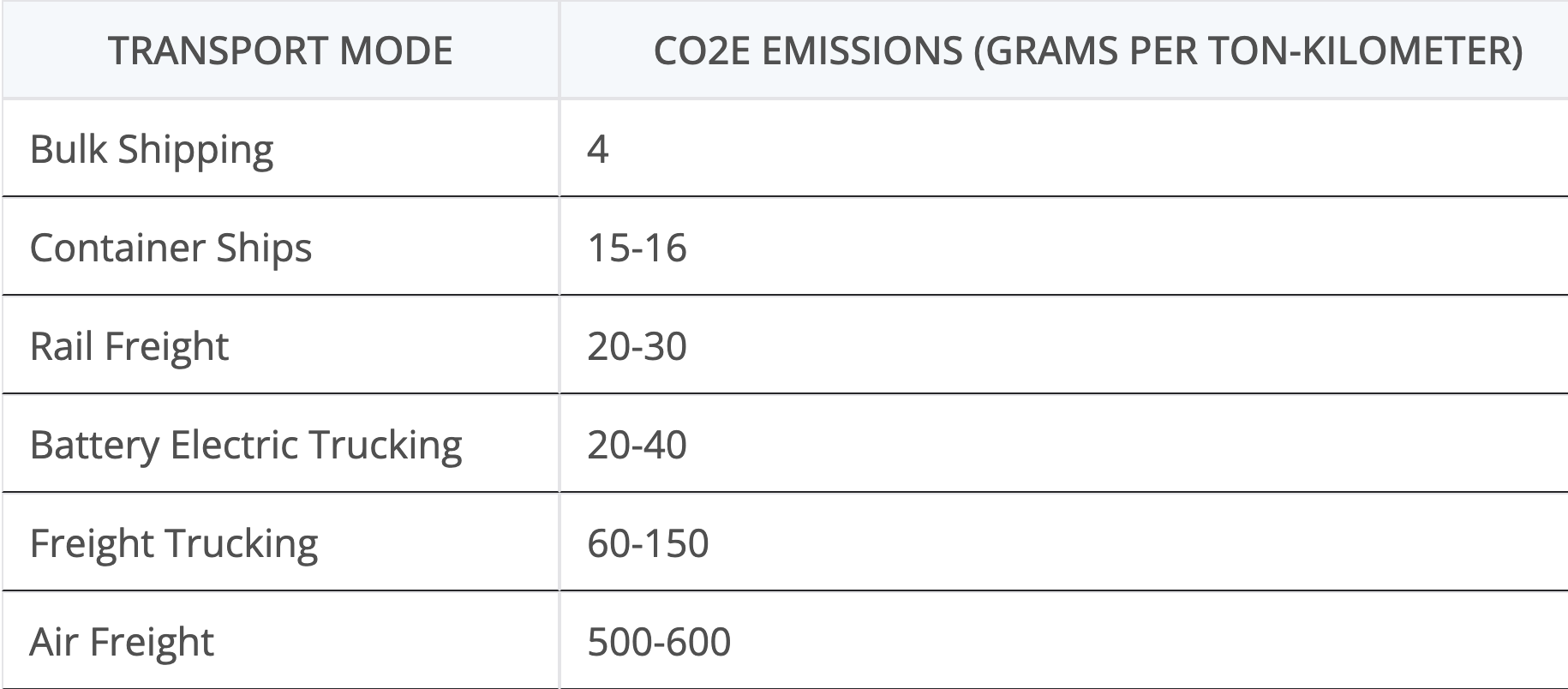

The table above includes electric trucking because it’s already lower CO2e per ton-kilometer than rail in 8 mostly affluent US states and about 70% of Canada, per an analysis I published a few months ago, and the breakeven is increasing regularly as grids decarbonize. This is because the USA and hence Canada and Mexico are outliers globally with no electrified freight rail. The rest of the world is well on the way to electrifying 100% of freight rail, with India going to achieve that milestone this year and China at over 70% rail electrification and rising. Not the point of this article, but worth noting.

Let’s take a ton of cargo, a flyspeck for a ship and a significant weight for a plane. Emissions are 30 to 40 times higher for freight shipped by air than by water. That would indeed be counterproductive if any supply chain manager or logistics coordinator opted for air due to carbon pricing. But do the numbers add up?

The shipping route from Shanghai to Los Angeles typically covers a distance of approximately 10,500 to 11,000 kilometers (about 6,500 to 6,835 miles) depending on the specific path taken and current maritime routes. Let’s call it 11,000 kilometers just for round-ish numbers. The Shanghai-LA route is one of the busiest in the world, so it’s nicely representative. The route doesn’t particularly matter for this calculation, or for that matter the distance.

The total emissions related to shipping 1 metric ton of cargo from Shanghai to Los Angeles by container ship are approximately 0.165 metric tons of CO2e. I used the IMO citation of 15 grams CO2e per metric ton-kilometer rather than Climatiq’s slightly higher 16.1 grams as container ships have slowed down a lot in the past few years. Slow steaming is one of the easiest levers to pull for decarbonization of freight shipping, as I pointed out in my assessment of efficiency levers for the sector while developing my projection of shipping through 2100 in 2022.

For context, a big 24,000 TEU container ship — a TEU is a twenty-foot-equivalent unit, the standard measure for container transshipment — will carry 230,000 to 250,000 tons of cargo. Any changes in course, headwinds, bad currents, deviations due to Houthis, sprinting across the ocean or slow steaming, or fouled hull or smooth will cause increases or decreases in fuel consumption that will be divided by almost a quarter of a million tons of cargo. That’s why shipping is the lowest carbon form of transportation, and that’s why every sensible transportation strategy at least aspires to shift more freight to water. As I noted recently regarding the USA, that’s a faint hope due to the Jones Act, which effectively holes domestic freight shipping, especially when combined with 40 years of deindustrialization.

It costs about $6,000 to ship a 40-foot container between Shanghai and LA at present, and the average mass of a loaded 40-foot container is about 20 tons. A 20-ft container costs from $2,500 to $4,000 and masses an average of 10 tons loaded. The cost for shipping a ton of cargo is about $300, in other words.

A carbon price of $150 to $300 would be equal to $25 to $50 for the ton of cargo, bringing the cost to $325 to $350.

The cost of air freight from Shanghai to Los Angeles varies based on the weight of the shipment and specific carrier rates. As of August 2024, the typical cost ranges from $4 to $6.5 per kilogram for shipments over 1,000 kg, and higher under a ton. Let’s call it $5. That’s $5,000 for a ton of cargo, about 15 times higher than the cost of shipping in container ships including carbon pricing.

Do you really think any supply chain manager is going to say, “Yeah, let’s use aviation because it’s going to be cheaper with carbon pricing” and not actually look at the math? They are going to use existing freight calculators and get quotes and then they are going to put the cargo in containers just as they do today, barring the requirement for very light goods to be in country very quickly.

Fast fashion is a climate disaster in part due to this. Fast fashion is a business model that emphasizes rapid production and delivery of trendy, affordable clothing to the market, ensuring a quick turnaround from design to store shelves. Fast fashion brands can bring new designs from concept to retail shelves in as little as two to four weeks. About 80% of China’s air cargo is fast fashion these days.

Basically, Fashion Week happens every six months in London, Paris, and Milan, mass market fast fashion types whip up knock-offs absurdly quickly, then ship them globally so that party boys and girls can be seen wearing something that was on runways a few weeks earlier. Then the glad rags get dumped into landfills. Vacuous and wasteful, yes, but also indicative of human nature.

During COVID 19, the only bright spot in aviation was air freight, but that was mostly of personal protective equipment, vaccines, drugs and related disease prevention, control, management, and amelioration materials and people. Outside of the brain-dead, fast fashion world, major manufacturers like Apple are working to completely eliminate air freight from their supply chains because of the rather horrific greenhouse gas emissions. Amazon builds distribution centers and stocks them based on AI-generated likely purchases so that as little as possible has to be flown in to meet service level agreements with customers (as well as pushing for sustainable aviation and shipping fuels and using electric trucks).

The additional carbon costs for shipping won’t be sufficient to make air freight remotely cost competitive. They will be sufficient to make biofuels and batteries worth transitioning to, although likely not hydrogen or e-fuels as they will be much more expensive. They will do the job they are expected to do, but they won’t cause any remotely sane person to put freight on airplanes instead.

Will this make shipped goods more expensive? After all, it’s either pay the carbon price or pay a bit less for electricity and biofuels. Surely those costs are going to be passed on to consumers?

Well, a packaged iPhone masses about half a kilogram. About 2,000 of them mass a ton. That $50 gets divided by 2,000, so that’s 2.5 cents per phone. The average iPhone is a $900 purchase. Shipping it across oceans isn’t a material cost.

What about heat pumps? A mini split heat pump system with one outdoor unit and two indoor heads masses about 70 kilograms, call it 80 with shipping packaging. That’s 12.5 in a ton. That’s $4 extra on a basic system which costs $3,000 to $5,000 just for the heat pumps (most of the cost is in the installation). Once again, it’s not material.

As noted, I’ve seen this argument that pricing shipping fuel carbon emissions would drive freight to airplanes. It doesn’t stand up to the slightest scrutiny.

Have a tip for CleanTechnica? Want to advertise? Want to suggest a guest for our CleanTech Talk podcast? Contact us here.

Latest CleanTechnica.TV Videos

CleanTechnica uses affiliate links. See our policy here.

CleanTechnica’s Comment Policy