Sign up for daily news updates from CleanTechnica on email. Or follow us on Google News!

New Flyer is the leading provider of transit buses in North America. It’s also the leading provider of hydrogen buses in North America, which is a problem for it, although it feels like an opportunity. That’s where the bad strategy comes in.

As always when I talk about strategy — unless I’m specifically talking about Franco-Prussian war military strategy, which I try to avoid — I start with Richard Rumelt’s kernel of good strategy. His book, Good Strategy Bad Strategy, is by far the best book to read on the subject, and I say that as someone who has been doing business and technical strategy for a couple of decades globally, and as an occupational hazard has read virtually every book on the subject. New Flyer’s executives, if they haven’t already, should pick up copies and read them carefully.

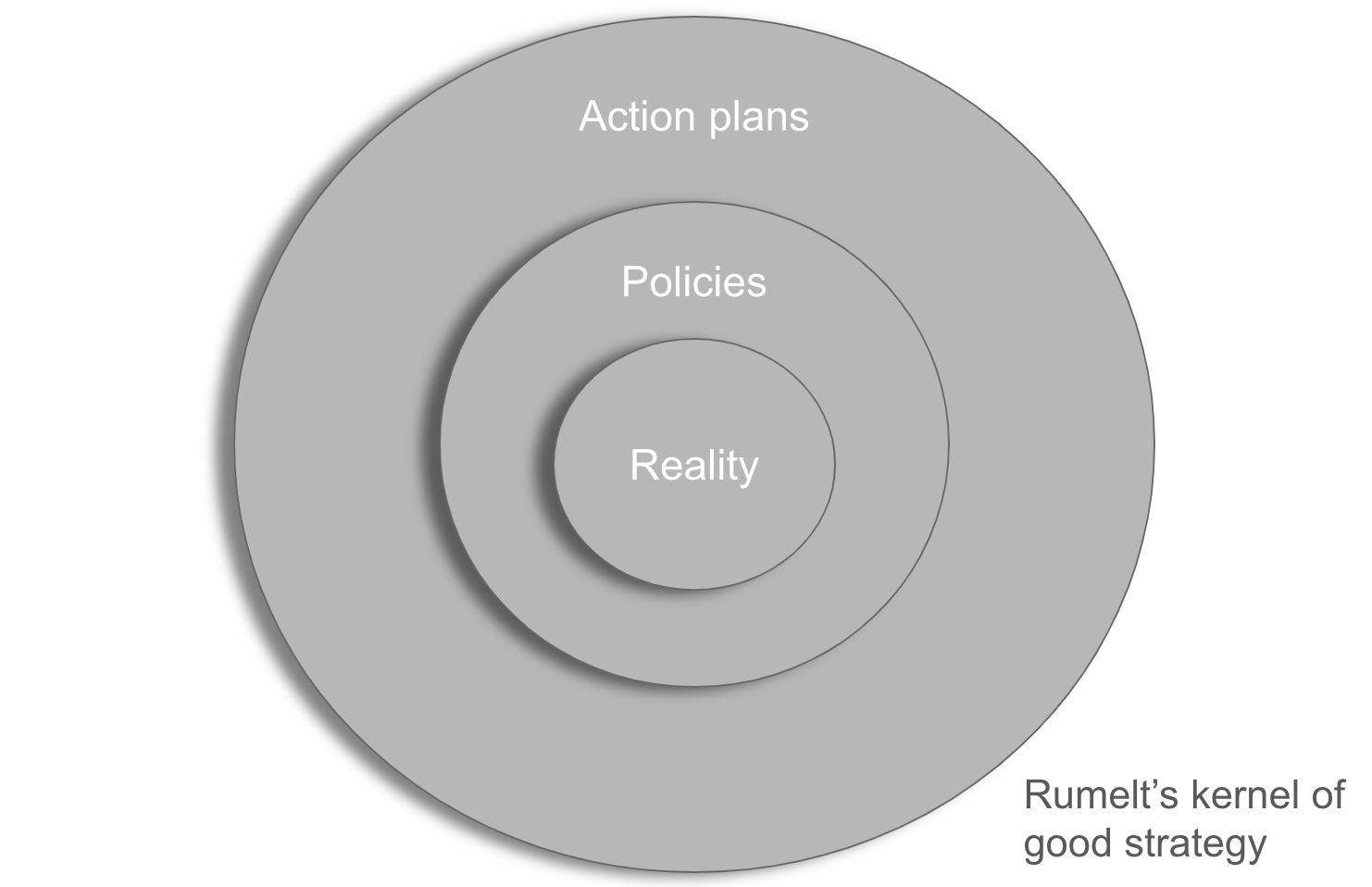

Rumelt’s position, backed up by decades of top level strategy work with corporations and governments, is that a good strategy has a kernel. First, it diagnoses what’s really going on. Second, it creates a simplifying and focusing policy or set of self-reinforcing policies that will enable the organization to exploit the upsides and avoid the downsides of the situation. Third, a set of connected actions plans that reinforce each other is created.

That’s it. Reality, policy, plan. It’s remarkable how many things called strategies don’t meet this really simple standard. And it’s remarkable how many fad business strategies don’t have them either. Pro tip: if the strategy book has a metaphor at its heart, for example Blue Ocean, it’s a tenuous set of connections somebody has observed that typically fails the test of time miserably, and not a useful prescription for how to think about your business.

And so, to New Flyer. It’s on my radar again because it’s complicit in the mess that CUTRIC is creating of Canadian transit decarbonization. CUTRIC’s study for Brampton led to that city choosing to go down a path which about 700 battery-electric buses and 400 hydrogen fuel cell buses. In theory, it was the cheapest of three options, beating battery-electric only by $10 million on a $9 billion price tag — an immaterial rounding error. CUTRIC is also working with Mississauga on its hydrogen bus pilot project and with Winnipeg on its hydrogen bus efforts.

Yes, there’s Winnipeg again. I’m sure Winnipeg’s transit agency is tightly coupled with New Flyer for better or for worse, and likely gets benefits from having the manufacturing expertise in the city.

I’ve done a deep dive into CUTRIC’s material with Michael Raynor, author and co-author of four books on strategy including The Innovator’s Dilemma and The Strategy Paradox, and until recently a managing director of sustainability and thought leadership with Deloitte. We found $1.5 billion in swings in favor of a battery-electric-only bus fleet, reducing the cost of that option by about $100 million and increasing the cost of the hydrogen side by over a billion. This was based on global data on actual costs of moving hydrogen around, battery costs, battery electric bus maintenance costs, hydrogen fuel cell costs, hydrogen refueling costs, and clear modeling choices that heavily skewed the analysis.

Perhaps the oddest thing about the study is that they didn’t do a cost benefit analysis, even ignoring Canada’s carbon price on emissions from different vehicles and their value chains. There was a $25 million swing against hydrogen just based on Canada’s carbon price actually being applied to manufacturing gray hydrogen. All CUTRIC did was an incomplete cost analysis with assumptions favoring hydrogen, leaving all of the emissions as informative, non-costed material.

It’s a fatally flawed study and CUTRIC delivering it is an existential threat to its existence as a useful advisor on transit. CleanTechnica and I received notice via a PR firm that they’d engaged that they were going to respond to the critique, and for those interested, I provided some strategic PR guidance for them in an open letter on LinkedIn.

New Flyer is a member of CUTRIC and has a seat on the Board, so this bad report is a problem for New Flyer as well. Or maybe they think it’s fine because they have clearly adopted the wrong strategy, one which isn’t in their self interest.

And so, to strategy. Let’s start with the diagnosis.

Globally, hydrogen buses have failed, just as hydrogen cars have failed. Battery-electric buses have won, just as battery-electric cars have won. Hydrogen buses cost more to buy, cost more to maintain, and cost a lot more to operate. They are less reliable than the alternatives. David Cebon, founder and director of the Centre for Sustainable Road Freight at Cambridge, and I collaborated on a fun little list of all of the hydrogen bus trials that have delivered the same answer since 1999, that they aren’t fit for purpose.

There are far more transit agencies that tried hydrogen buses, ditched them, then pivoted solely to battery-electric buses than there are operational hydrogen bus fleets in the world. And this has played out in China, where the test was run over the past 15 years. The answer? Over 600,000 battery-electric buses and under 10,000 fuel cell buses, mostly in Foshan, a city which made a bad strategic bet on becoming the manufacturing hub for fuel cell vehicles. Even Foshan had to shut down its hydrogen tram recently because it was too expensive.

But there is governmental money to be had from hydrogen, quite a lot of it. Canada, for example, will subsidize up to 50% of capital costs for a tank-to-wheel, zero-carbon transit system, even one with gray hydrogen where the emissions from manufacturing the hydrogen and then leaks along the way provide no carbon emissions reduction benefits. The EU’s JIVE program has dispensed $1.2 billion for hydrogen fleets and research in the past 25 years, and per its status reports, has virtually nothing to show for it. California, like the EU suffering from the hangover of being an early leader in addressing climate change and hence having bureaucratic, funding, and lobbying inertia, continues to throw good money after bad in the space.

On that last point, California’s hydrogen bus fleet costs 50% more to maintain than diesel and double battery-electric. Its hydrogen refueling systems fail regularly. The hydrogen heads are trying to hide the reality, issuing reports that aren’t covered in red ink, instead claiming success with confusing numbers, but the reality is seeping out.

In most cases, buying a hydrogen bus system will result in more subsidies, even though results for transit agencies will be much worse, and system greenhouse gas emissions will be much higher. Wise transit agencies are taking and will take less money from federal and state subsidies and get better battery-electric systems only. Unwise ones go down the hydrogen path and in the absence of external pressures ditch them and buy battery-electric. If there’s external pressure, they and their transit customers will be poorer for it in real dollars and service quality. The external pressure will eventually disappear, mostly because it’s based on bad assumptions or false hopes, and all transit agencies that were forced into hydrogen will go electric.

Okay, so in the end, battery-electric will be the winner everywhere, but in the meantime there’s a lot of governmental money being thrown around. What should New Flyer do?

Clearly, they have settled on one policy now, which is that they will actively support customers buying hydrogen buses as well as battery-electric buses, diesel buses, and CNG buses. It probably seems like a better one for them, but it’s a weak analysis.

Why does it seem better? Because they charge more for their hydrogen fuel cell buses than for their battery-electric buses, probably a lot more. And to be clear, that price difference is just going to expand for the coming decade as battery prices continue to plummet, and fuel cells with their attendant suite of air, water, and hydrogen, thermal, and quality management components remain expensive for the cells and expensive to manufacture. Battery-electric buses are much cheaper to build and getting cheaper.

From New Flyer’s perspective, this seems like a win-win for it. The company gets to charge more per unit. And Canada’s subsidy policies support this waste of money, so transit agencies are only out of pocket for 50% of capital costs.

But it’s a strategic trap for New Flyer, in a couple of ways.

Every customer it sells its fuel cell buses to are going to be unhappy customers. Hydrogen buses are inferior products from a transit perspective, coming and going. Transit agencies like London find that they can meet 100% of route needs with battery-electric, but fuel cell buses don’t actually meet all the route needs. Fleets globally are finding that their hydrogen buses are out of service regularly, so they are running extra diesel buses a lot to make up for it. That’s due to fuel cell failures, complex hydrogen bus system failures, hydrogen refueling system failures — compressors especially are highly failure prone — or hydrogen shortages. Those problems aren’t going away.

Transit agencies are going to look at New Flyer and wonder why it was selling them an inferior product — a product that has been demonstrated over and over again globally to be inferior — for a much higher price, and not just selling them battery-electric buses. They expect that if New Flyer sells them something, it’s going to be as good as or better than the diesel buses they’ve been buying for decades, and they expect New Flyer to steer them right in terms of options.

Further, all of that additional cost and complexity of manufacturing means that New Flyer isn’t focusing fully on building as many battery-electric buses as it can, keeping a lock on the North American bus market of the future. While there’s a lot of money flowing around, building hydrogen buses reduces the total number of buses that New Flyer can build. It’s complex to have to maintain all of the facilities, staff, operational procedures, and safety for fuel cells, pressurized hydrogen, and the like. More parts for maintenance and different maintenance staff add costs. They need capital for the plants and the components against future revenue.

BYD is already manufacturing battery-electric buses in a factory in California. BYD is now the bigger manufacturer and seller of cars and light trucks with plugs, and second only to Yutong as the provider of battery-electric buses in China and globally. It’s delivering battery-electric buses to Europe as well. It’s booking orders for hundreds of battery-electric buses in the USA. Notably, the Los Angeles Department of Transportation (LADOT) placed an order for 130 of BYD’s K7M electric buses, marking one of the largest single electric bus orders in U.S. history.

New Flyer is losing market share to BYD by selling hydrogen fuel cell buses. New Flyer is creating unhappy customers by selling them hydrogen buses. New Flyer is making itself a target for future customer wrath by being part of CUTRIC’s failures related to analysis and thought leadership.

What other policy could New Flyer choose? It could intentionally cede the hydrogen bus market to ElDorado National California (ENC), a reasonably big but distinctly secondary bus manufacturer in the USA. BYD might get a slice of that market too, as they do offer a hydrogen fuel cell range extender, one that they’ve provided for Hawaii.

That way, they would let competitors get the dissatisfied customers and focus on making and selling a lot more battery-electric buses. That’s a much more sustainable business model. It’s also good marketing, as they could lean into hydrogen’s systemic end-to-end emissions and global failures, saying that while the money is good, it wants to do right by its customers and the world. It would make its cost of building battery-electric buses cheaper due to the increased units and amortization of fixed costs across them. Its total cost of capital would be lower, as would its certification process costs.

Is there some sort of unit cap on this that might be skewing their thinking? No. New Flyer at peak delivered about 6,500 units in a single year in North America. That’s the maximum manufacturing peak when it was delivering no battery-electric or hydrogen buses at all, almost entirely diesel and some CNG buses. It’s running well under that, about 5,700 in 2019 and about 4,800 across all NFI brands in 2022, per the data I have.

There are about 78,000 buses in the USA alone that have to be replaced as rapidly as possible to decarbonize transportation, and more in Canada and Mexico. They are all going to be battery-electric. New Flyer could work flat out for the full replacement cycle for urban transit buses at 6,000 buses a year and never run out of work.

It’s likely that every hydrogen bus New Flyer manages to sell will cost it three battery-electric bus sales. BYD will be selling transit agencies all of those buses, creating more satisfied customers. If New Flyer persists with pushing hydrogen, in 20 years, it will be a shadow of its former self, BYD will dominate the North American market, and New Flyer’s very existence will be in doubt.

Chip in a few dollars a month to help support independent cleantech coverage that helps to accelerate the cleantech revolution!

Have a tip for CleanTechnica? Want to advertise? Want to suggest a guest for our CleanTech Talk podcast? Contact us here.

Sign up for our daily newsletter for 15 new cleantech stories a day. Or sign up for our weekly one if daily is too frequent.

CleanTechnica uses affiliate links. See our policy here.

CleanTechnica’s Comment Policy