Sign up for daily news updates from CleanTechnica on email. Or follow us on Google News!

One thing that the hydrogen for energy chorus is good at is celebrating and amplifying acts 2 and 3 of the Odyssey of the Hydrogen Fleet, when governments unlock millions or tens of millions for hydrogen trials and cash-starved fleet owners throw it at a handful of hydrogen buses, trucks or trains. One thing that the chorus is bad at is even acknowledging, never mind keeping track of, acts 4, 5 and 6, where the governmental taps are shut, leading to the fleet operators scrapping the hydrogen vehicles and getting battery electric vehicles instead, something that they should have started with.

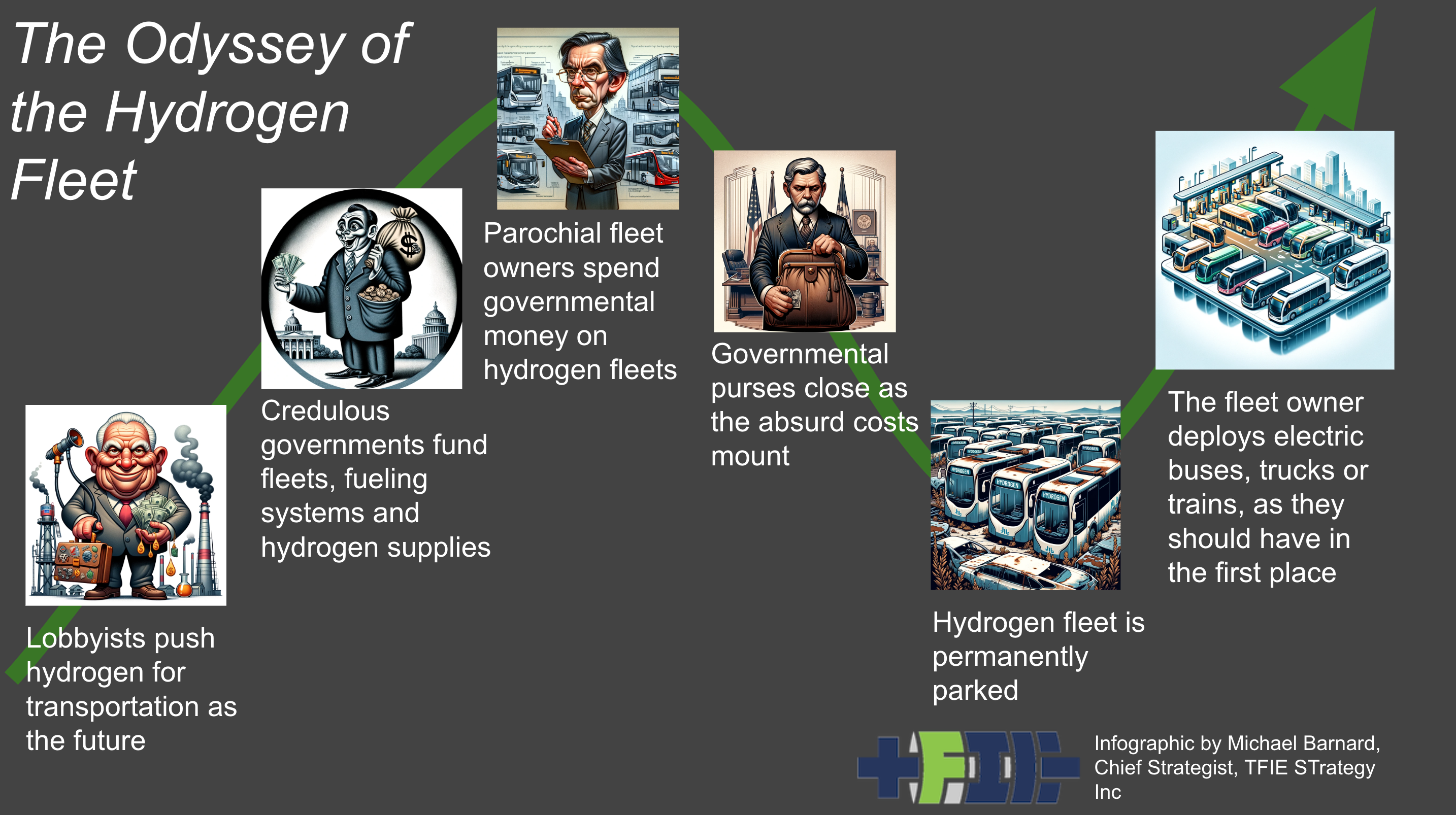

To assist the hydrogen chorus to overcome their cognitive biases, and as an informational inoculation for governmental apparatchiks and fleet operators that are lagging in decarbonization, I’ve been having a bit of fun writing out and creating an infographic for the inevitable progression of hydrogen fleets, and listing where examples are on the trajectory.

In the first installment, I covered three continents. In Europe, France had an entrant, with the commune of Pau abandoning its expensive, hard-to-keep running municipal buses this year. When I say expensive, the funding was roughly a million euros per bus, when an equivalent Yutong electric bus is roughly a third that price. Germany had a couple of entrants, with Lower Saxony shuffling its 14 €6.7 million each small hydrogen passenger trains onto sidings to rust, something the nearby state of Württemberg avoided simply by doing a little work with spreadsheets.

Not to be outdone, Austria gave a million euros per vehicle to Ikea — because that global furniture behemoth is strapped for cash? — for five hydrogen delivery trucks, when €85,000 euros would have bought a battery electric delivery truck with equal range that could use the 22,000 public electric vehicle charge points in the country. Ikea’s poor hydrogen truck drivers, at least until the government stops paying for the hydrogen, will spend most of their time driving to and from the total of seven hydrogen refueling stations in the country.

While India is rapidly grid-tying its heavy rail, with the expectation of reaching 100% electrification in the next year, it also bought a handful of tiny hydrogen trains to run over legacy heritage tracks carrying tourists.

In North America, the epicenter of hydrogen fleet irrationality is California, which like Germany is suffering from the hangover of being an early leader in decarbonization. It has legacy laws, funding, a scattering of infrastructure and a big hydrogen chorus, so keeps making the same mistakes over and over. Enter Santa Cruz, with yet another million per bus entrant in the tragicomedy.

In the second installment I returned to Europe, where Bavaria has finished testing of a single, tiny, two-car hydrogen train and is going to put it into operation for a few months in 2024 before shunting it onto a siding, never to be heard from again. Canada had a brief call out for Quebec’s three month, multi-million dollar trial of a tiny tourist train on rural tracks this summer, something which at least had the distinction of being explicitly time-limited, but where the stench of historical Bombardier corporate welfare hung over the transaction, that long-lasting Quebec firm’s train division having been swallowed whole by Alstom a handful of years ago.

And now, a few more enactments of this play to round out the current list. As I’ve been writing these amusing tales in which the hydrogen chorus discordantly howls with joy at every tiny glimmer of immaterial volumes of vehicles running on their favorite gas, while averting their eyes and clamping shut their lips when the fleets are abandoned to rust, collaborators from around the world have been providing new examples of places where the tragicomedy has unfolded or is unfolding.

Let’s start by traveling back in time, to some of the first stagings of this play. Perhaps fittingly, one opened so far off Broadway and so long ago that its setting became a jet set de rigeur stop over in the heady days of trust fund hipsters in the late 2000s, before the sub-prime mortgage disaster erased their ability to skip lightly over the constraints of having actual jobs. Yes, we’re talking Reykjavik in Iceland, and I wish I were kidding about it being a hot place to party prior to the Great Recession. That all came to crashing halt in 2008, of course, and Iceland remains the only country that jailed the bankers responsible for the fiscal meltdown, a lesson that other countries could have learned from.

Other countries could have learned from their hydrogen tragicomedy as well. At some point in those heady days Iceland had made the bold claim that it would be the first hydrogen economy in the world. They opened the first hydrogen refueling station in the world in 2003, the Shell station in Grjótháls, which in 2008 was being referred to as a ghost station as it sat there, unused.

The first fleet was, unsurprisingly, buses, a trial that the legendary wind energy raconteur Paul Gipe pointed out to me. The European ECTOS program had three buses on the basaltic roads of the island nation from roughly 2001 to 2005, when the buses were inevitably mothballed. The program was expected to cost €7 million with the EU chipping in a million euros per bus. That’s about €12 million in 2023 dollars, so they definitely paid a steep price for being one of the first failures in a long, long string of them over the past two decades. Iceland stayed in the pan-European hydrogen effort, with three hydrogen refueling stations in the country at one point.

Somewhere in there, they retrofitted a fuel cell and some hydrogen tanks onto a tourist boat as an auxiliary power unit, not a drive unit. That lasted about a year as far as I can tell before being predictably abandoned.

Despite 20 years of failures and abandonment, there are still two operating refueling stations and 20 whole fuel cell road vehicles in the country, mostly in a fleet of taxis. The fleet was, naturally, paid for by EU grants, specifically the Fuel Cells and Hydrogen 2 Joint Undertaking (now Clean Hydrogen Partnership) under Grant Agreement No 671438 & No 700350. I’m sure somewhere in Brussels someone knows exactly how many millions of euros were shipped to Iceland for these fool cell taxis, but it’s not something accessible via Google in English.

The 2020 Icelandic €300 million climate package includes the potential for funding hydrogen vehicles despite 20 years of utter failure, which is saying something. Like California and Germany, early efforts to be virtuous have led to a calcification of hydrogen bureaucracy, proponents and refusal to accept constant failure as evidence of the inappropriateness of hydrogen as a fleet transportation fuel.

By my count, the tiny island nation of Iceland, with its 360,000 people, has the highest per capita runs of the tragicomedy, three plays, two of which closed out in the 2000s, but with the taxi fleet revival in act 3 now.

Let’s leave the North Atlantic and head to the Pacific Northeast, to British Columbia. It received an honorable mention in a preceding article, as the vast majority of hydrogen refueling stations in Canada — five out of the total of six — as well as the headquarters of perennial hydrogen debutante Ballard Power are within the boundaries of the mountainous province. And with the existence of barely used refueling stations, there must have been local enactments of the tragicomedy.

Let’s go north from Vancouver, driving up the absurdly scenic Sea to Sky Highway, past the 300 meter plunge of Shannon Falls, through Squamish, home of hypothermic kite surfers, and on to Whistler BC. Take care in driving, especially on Fridays after work, as adrenaline junkies are driving at exotic speeds in order to start risking life and limb as rapidly as possible in the kilometer of vertical playground in the ski and mountain bike mecca.

That playground was on full display in 2010, when the Winter Olympics were hosted in British Columbia. And with the boondoggle that is the modern Olympics comes transportation boondoggles. In Paris next summer many people are pretending that electric flying taxis will get their great global debut at the event, something that’s both deeply unlikely to actually occur, and if it occurs, deeply unlikely to turn into anything more than carnival rides. But in Whistler, the transportation boondoggle was hydrogen buses, 20 of them, powered by Ballard fuel cells, and funded with C$94 million of taxpayer money, almost $5 million per bus.

The green hydrogen was being trucked — trucked! — from Quebec, roughly 4,500 kilometers away because there wasn’t a sufficient supply of the stuff in BC. As a reminder, it takes about 14 tube trailers of hydrogen to replace a tanker trailer of diesel, so that was an awful lot of 250 atmosphere hydrogen trucks powered by diesel driving back and forth across the country doing 9,000 kilometer round trips. The state of the art steel tube trailers of the time carried about 380 kilograms of hydrogen each, the energy equivalent of 1,400 liters of diesel, although fuel cells are a bit more efficient than a diesel bus engine, so it’s more like the equivalent of 2,000 liters. That’s enough for perhaps 10,000 kilometers of bus driving.

Yes, every bus in the Whistler fleet required about 9,000 kilometers of diesel trucking distance for every 10,000 kilometers of bus travel. Ballard brags still that the 20 buses covered over a million kilometers in their first year or so. That meant that about 100 hydrogen tube semi trucks driving 900,000 kilometers back and forth on the Trans Canada Highway. The four years of the trial probably required four million completely unnecessary kilometers of highway diesel truck traffic between Quebec and BC.

Oh, and the fuel cell buses didn’t like even the mild Whistler winters, as the water vapor created by fuel cells tended to freeze up inside of them and bring them to a halt by the side of snowy roads. Remember, Whistler is a ski town and these buses were deployed for the Winter Olympics, yet they weren’t capable of dealing with even mild winter conditions. Amusingly, one of the stories the hydrogen chorus still tells is that the advantage of hydrogen buses over battery electric is winter driving.

The buses were, of course, abandoned entirely in 2014. Various politicians since, seduced into thinking that the hydrogen for energy economy was just around the corner by Ballard lobbyists and holdover local chorus members, have proposed massive new funding schemes for hydrogen. But, of course, all of the transit organizations are going battery electric as fast as they can, and buying biodiesel to bridge their legacy buses to retirement. No hydrogen fleets still on the roads of BC as far as I’m aware.

And finally, one last Canadian story before I tuck this series into bed before Christmas, this one from Quebec again. Another correspondent provided me with an article from le journal de quebec headlined “After $6 million spent: no more government hydrogen cars“, at least according to Chrome’s automatic translation.

In 2018, the government of Quebec decided that becoming a green hydrogen power player with all of its excess, uncommitted hydroelectricity — something which evaporated this year when they realized that they had actually overcommitted their GW of capacity, leading to embarrassing headlines about Quebec refusing to provide electricity for green hydrogen plants — was a great idea. As part of that initiative, they decided to create a hydrogen light vehicle test center. That’s what led to the sole hydrogen refueling station outside of the weird bubble of BC.

And it also led to the Quebec government leasing 50 Toyota Mirai cars for governmental use for the standard four year term. As a reminder, Toyota doesn’t sell Mirais, it only leases them, and the only reason most private drivers take them up on that is due to Toyota providing US$15,000 in free hydrogen refueling, something which at California’s current hydrogen refueling costs provides about 2.5 years of free driving. One internet wag pointed out that leasing a used Mirai for $10,000 or $15,000 was well worth it, if you happened to mostly drive around the limited parts of California with refueling stations that actually worked.

The Quebec hydrogen refueling station, barely used, dusty and ignored by the drivers who pull into the Esso station it’s located with in the suburban wilds of Quebec City, cost over $5 million for its single vehicle at a time capacity. Outside of the governmental cars, which apparently governmental workers barely used, there were only 20 registered fuel cell vehicles in all of Quebec in 2022. Meanwhile, Quebec leads Canada in electric vehicles, with 43% of new vehicles being battery electric and 2 million registered electric vehicles likely early in 2024. Now the 50 Mirais are back on Toyota’s hands, being refurbished for the next suckers.

The government didn’t make an announcement about this. They refused comment in fact. Local academics are moaning about the complete lack of transparency and reporting. The government is claiming it will release a full report in 2024, but I expect not.

After all, Quebec is in the grips of hydrogen for energy fever again, hoping to spin up an industrial giant to replace Bombardier, which not only sold off its entire rail business but all of its aviation business except for some executive jet maintenance work. It’s not like the other perennial corporate welfare recipient, SNC Lavalin, is picking up the slack, as its revenues are 20% off its 2019 peak, and the small modular reactor project at the Bruce Nuclear Plant in Ontario, while undoubtedly good for tens of millions of padded invoices, isn’t going to be paying many Quebecois salaries.

That the Quebec government just abandoned its flagship green hydrogen vehicle fleet isn’t a great PR story for the province being a new energy industrial hub. Naturally, the hydrogen chorus is completely silent on this latest debacle and thinks the tiny hydrogen tourist train is both vastly bigger than it was, and still operating. Their ability to ignore inconvenient facts is one of the things preventing rational decision making.

Have a tip for CleanTechnica? Want to advertise? Want to suggest a guest for our CleanTech Talk podcast? Contact us here.

Our Latest EVObsession Video

I don’t like paywalls. You don’t like paywalls. Who likes paywalls? Here at CleanTechnica, we implemented a limited paywall for a while, but it always felt wrong — and it was always tough to decide what we should put behind there. In theory, your most exclusive and best content goes behind a paywall. But then fewer people read it!! So, we’ve decided to completely nix paywalls here at CleanTechnica. But…

Thank you!

CleanTechnica uses affiliate links. See our policy here.