New research has pinpointed the concentration and distribution of lithium across Australian soil, providing crucial insights for identifying potential reserves in the country.

Australia’s lithium exploration has predominantly centered in Western Australia, but this research indicates the potential of other Australian regions, including Queensland, New South Wales and Victoria, that display elevated predicted lithium densities.

Lithium is a valuable mineral increasing in global demand for its applications in batteries, phones, laptops and electric vehicles. The study, published in the journal Earth System Science Data, was led by researchers at the University of Sydney with co-authors from Geoscience Australia.

Lead author Dr Wartini Ng, a Postdoctoral Research Fellow in Soil Security from the School of Life and Environmental Sciences, said: “Our research not only opens up new possibilities for Australia’s lithium industry but could also advance our path towards a low-carbon economy, a critical step in curbing greenhouse gas emissions.”

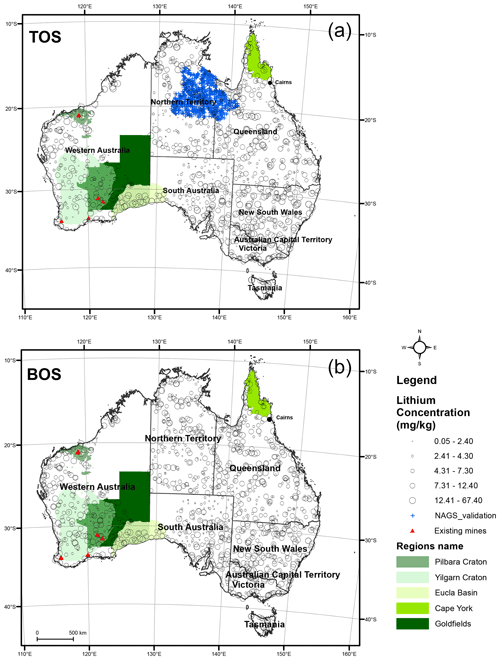

Figure 1Distribution of sampling sites from the National Geochemical Survey of Australia (NGSA, black circles) for both depths: top outlet sediment (TOS) 0–10 cm (a) and bottom outlet sediment (BOS) ∼60–80 cm (b). Distribution of sampling sites from the Northern Australia Geochemical Survey (NAGS, blue plus signs) for TOS only (a). All data refer to the coarse fractions (<2 mm). Aqua-regia-soluble Li concentrations (mg kg−1) are categorised in five quantile classes. Regions discussed in the text are highlighted in various shades of green. Projection: Australian Albers equal area (EPSG:3577). Data sources: de Caritat and Cooper (2011b), Hughes (2020), and Main et al. (2019).

Senior study author Professor Budiman Minasny, one of the leading international scientists in soil mapping and modelling, said that the findings could have significant implications for the lithium industry in Australia.

“We’ve developed the first map of lithium in Australian soils which identifies areas with elevated concentrations,” Professor Minasny said. “The map agrees with existing mines and highlights areas that can be potential future lithium sources.”

Professor Minasny is from the University of Sydney’s School of Life and Environmental Sciences, and a member of the Sydney Institute of Agriculture, China Studies Centre and Sydney Southeast Asia Centre.

The study indicates the highest lithium concentrations are found near the Mount Marion deposit of Western Australia, with elevated concentration across the central western region of Queensland, southern New South Wales and parts of Victoria.

The team used digital soil mapping techniques developed at the University of Sydney to gauge extractable lithium content present in soil samples collected across Australia.

The research paints a comprehensive overview of lithium distribution across the continent, which is influenced by a variety of environmental factors including climate, geology and vegetation.

Declaration: The authors declare no competing interests. This research was supported by the Australian Research Council, the Australian Government and the Exploring for the Future Initiative. The researchers acknowledged the traditional custodians of the lands on which the samples were collected and thanked all landowners for granting access to the sampling sites.

Courtesy of the University of Sydney. Digital soil mapping of lithium in Australia images by Ng et al. via Earth System Science Data, Copernicus Publications.

I don’t like paywalls. You don’t like paywalls. Who likes paywalls? Here at CleanTechnica, we implemented a limited paywall for a while, but it always felt wrong — and it was always tough to decide what we should put behind there. In theory, your most exclusive and best content goes behind a paywall. But then fewer people read it! We just don’t like paywalls, and so we’ve decided to ditch ours. Unfortunately, the media business is still a tough, cut-throat business with tiny margins. It’s a never-ending Olympic challenge to stay above water or even perhaps — gasp — grow. So …