Sign up for daily news updates from CleanTechnica on email. Or follow us on Google News!

Major shipping firm A.P. Moller – Maersk continues to invest in green methanol and dual-fuel ships to burn it in. The firm made the choice for green methanol as its decarbonization strategy and is executing. While I think that green methanol is merely the best of the also-ran alternatives for the space, with batteries and biofuels being the much more reasonable and stronger contenders, I respect their choice.

But there are nuances in their approach worth considering. The news which triggered this was that Maersk did execute on something that had been in the works. Reports indicate that the firm has bought half of an Egyptian wind farm intended to fuel green methanol manufacturing next to the Suez Canal.

I first published on the Egyptian plans in early 2022, when I was engaged to assess European hydrogen initiatives in northern Africa. Egypt is providing significant fiscal tax breaks for green hydrogen, ammonia and methanol initiatives, and space in the Ain Sokhna economic zone beside the canal.

Not long ago, Maersk’s first dual-fuel ship slid into the water in South Korea for its long journey to Denmark. While Maersk promoted its use of green methanol, sourced from biomethane at a U.S. landfill, the presumed transportation of this fuel over 10,000 km to Ulsan raises questions about its environmental impact. Furthermore, the Maersk ship needed to refuel multiple times during its journey, in Singapore and Egypt, leading to uncertainties about the type of fuel being used. There were doubts regarding whether the Singaporean tanker, which may have transported the green methanol, is using unabated methanol with higher CO2e emissions than diesel, or if it’s using diesel itself.

In fact, it’s been revealed that Maerk’s dual-fuel ships, when they run on methanol at all, will be very unlikely to be burning green methanol directly, at least not for a long time. Due to the very obvious logistical challenges of getting relatively tiny amounts of green methanol to a large number of ports that don’t have it, Maersk instead is effectively doing what Microsoft does when it buys wind power hundreds of kilometers away from a data center. It’s using whatever methanol is available locally, and paying for the creation of green methanol which will be used by some other end user somewhere else.

In principle, this is the same as Microsoft’s acquisition of green electrons, however, there are some nuances worth attending to. Let’s start with basic methanol for shipping. It’s wood alcohol, which means it burns cleanly, but non-green methanol is a much bigger carbon problem than marine diesel or resid.

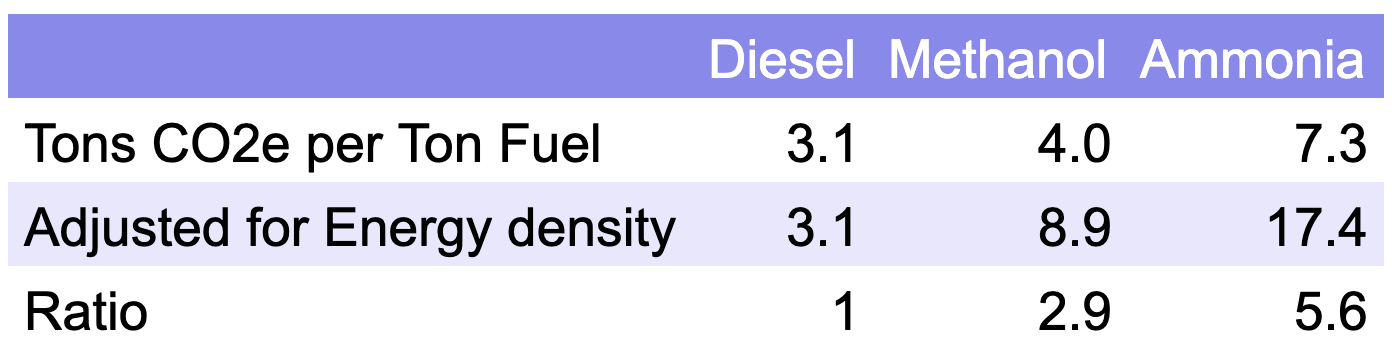

Table of CO2e emissions for diesel, methanol and ammonia as a maritime fuel

I created this table a while ago based on the Methanol Institute’s numbers for carbon emissions in manufacturing of the liquid. The average of methanols around the world emit 2.9 times as much greenhouse gas as marine diesel does, so clearly that’s not a climate win.

At present, manufacturing methanol from natural gas, coal gas, and other gases has a carbon footprint of 500 to 700 million tons of carbon dioxide or equivalent globally. That’s in the range of 1-2% of global greenhouse gas emissions. It’s a big climate problem.

The Institute is the global lobbying arm for the industry and it really doesn’t like this reality and makes sure it never does the comparison itself in any documents. At the same time, it’s pushing hard for methanol to be the ‘low-carbon’ shipping fuel of the future.

The industry has been selling high carbon methanol as a ‘clean burning’ fuel to the shipping industry for years and promising that actually green methanol would be the same price as marine shipping fuels today. It’s very much a bait and switch, and it is working on Maersk and others. Many people are under the illusion that green hydrogen will be cheap, so Maersk isn’t alone in making this mistake.

Methanol is already more expensive today than marine fuels, an average of 1.6 times the cost of marine diesel across major jurisdictions. In the future, it will be much more expensive, as like hydrogen it can be green but won’t be cheap through either directly assembling synthetic methanol using very well understood chemical engineering processes, or manufacturing it from biomethane. It is likely to be two to five times the cost in fact, or three to eight times the cost of current maritime shipping fuel.

This too is something the Institute really doesn’t want anyone to understand, and Maersk is only likely to be beginning to understand as it signs contracts for biomethanol and synthetic methanol. I strongly suspect the methanol manufacturers supplying it are providing it at or below cost in the short term to get Maersk and others hooked, with the reality of higher prices unveiled only later. If true, is that a legal business practice? Sure, as long as you aren’t colluding across the industry to do so or creating a massive monopoly through unfair pricing practices. Is it ethical? Not so much. Is it a good climate solution? Not really.

If methanol becomes the marine shipping fuel of the future, in my projection of energy requirements for portions that won’t electrify, methanol demand would likely triple to closer to 500 million tons. In energy projections which pretend that shipping will increase substantially and ignore electrification, the methanol demand would be well over a billion tons a year. You can see why the methanol industry is working so hard to make this the energy source of choice.

But to be clear, Maersk’s efforts are much more virtuous than Methanex’ Atlantic crossing by a ship powered by purportedly green methanol that was actually 96% fossil natural gas derived. That was some of the most egregious greenwashing I’ve seen in the space. But how virtuous is ensuring that some of methanol in circulation is green?

One upside of Maersk ensuring that green methanol is manufactured is that it is creating a market and enabling efficiencies and economies to be found in deployed sites. We don’t make green methanol today because natural and coal gas is dirt cheap, so there’s very little experience with synthesizing it at an industrial scale or manufacturing it from biomethane, although the latter is much more aligned with current industrial practices. Maersk putting money into that is good because the methanol industry globally has to decarbonize in order for climate goals to be met.

There’s also a strong argument that the green methanol it purchased for the long initial journey was very green. It was manufactured from biomethane emitted from landfills in the USA. Methane is a much more potent greenhouse gas than carbon dioxide, and our food waste, livestock dung, wood chips and agricultural stalk waste is a very large climate problem as well. Diverting biomethane that we are unintentionally creating into methanol is an excellent way to make it a deeply carbon negative industrial product. That said, landfills have been required for years to capture or burn off the methane that comes from them in the developed world, so the odds that the green methanol was made from biomethane that would otherwise have been vented to the atmosphere are low.

The big down side is that Maersk is not taking any of those legacy methanol emissions off the board. It’s buying additional methanol that would not otherwise be manufactured. Its use of methanol as a shipping fuel is in addition to the roughly 170 million tons manufactured annually.

Job one for major climate problems is to fix the emissions of the current products or reduce the use of them, not multiply demand for them.

Multiplying demand for methanol isn’t like increasing electricity demand. That commodity already powers industry, commerce, transportation, heating, and lighting everywhere, and everyone uses it. A data center, for example, while a big power draw, is still a tiny fraction of electricity. Methanol is a much more narrowly industrial feedstock, one that isn’t burned. Multiplying demand for it and having that use case explicitly create carbon dioxide is at the other end of the spectrum.

There is another advantage to methanol worth mentioning. It doesn’t create nearly as much air pollution in ports as ships steam in and out, and as they sit in ports running their auxiliary power units. That’s nice. It’s also somewhat irrelevant as the same results can be met with much lower concerns with hybrid battery-electric drivetrains and mooring provision on auxiliary power, something that’s already spreading quickly.

My expectations of what will actually happen with Maersk’s dual-fuel ships remain unchanged. As the price and footprint of methanol sinks in, and as they get carbon-priced by the EU emissions trading scheme and carbon border adjustment mechanisms, the ships will end up bunkering biodiesel and almost never burn methanol. It will be cheaper, vastly more available in ports and be more climate friendly. The real pathway for shipping which doesn’t just electrify completely is dual-fuel with electrons and biofuels.

Have a tip for CleanTechnica? Want to advertise? Want to suggest a guest for our CleanTech Talk podcast? Contact us here.

EV Obsession Daily!

I don’t like paywalls. You don’t like paywalls. Who likes paywalls? Here at CleanTechnica, we implemented a limited paywall for a while, but it always felt wrong — and it was always tough to decide what we should put behind there. In theory, your most exclusive and best content goes behind a paywall. But then fewer people read it!! So, we’ve decided to completely nix paywalls here at CleanTechnica. But…

Thank you!

Tesla Sales in 2023, 2024, and 2030

CleanTechnica uses affiliate links. See our policy here.

.jpg)