Support CleanTechnica’s work through a Substack subscription or on Stripe.

Up until now, San Bruno, California was famous for two things. It is where San Francisco International Airport is located and it is where Suzanne Somers grew up. Now it has a third thing to celebrate. It is home to the headquarters of Electroflow Technologies, a company that says it has cracked the code for how to extract battery-grade lithium from brine to create LFP powder in a way that is so effective the end product is 40 percent cheaper than lithium from Chinese suppliers.

On its website, Electroflow says, “Brines in North America contain enough lithium to produce over 300 million electric vehicles, yet these resources have been barely touched. With our technology, we can extract lithium from dilute brines, which unlocks 75 percent of the lithium stored in brine in the US. We envision a world where lithium and other critical materials are no longer a bottleneck in the clean energy transition. In this new world, mineral abundance is achieved through sustainable practices.”

Simplifying The Process Lowers Costs

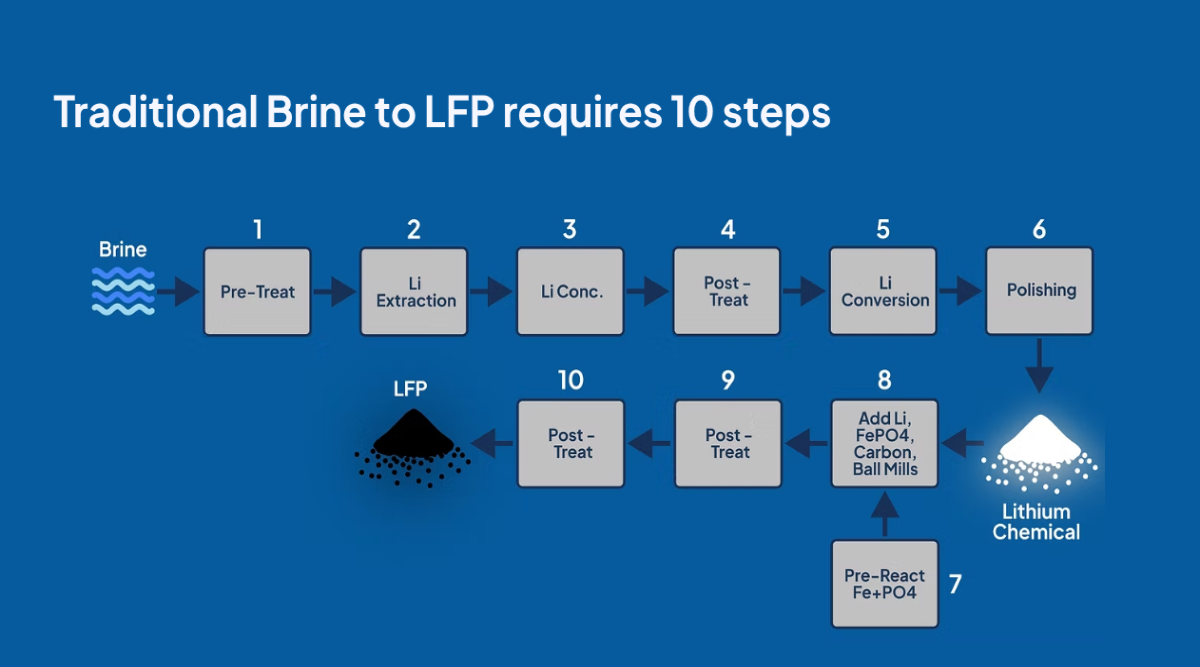

The secret sauce for Electroflow is a proprietary process that produces battery-grade LFP powder from brine in just three steps. Normally, the process requires ten. “We think LFP is the missing ingredient for energy prosperity. The problem is it’s literally 99 percent made in China,” Eric McShane, co-founder and CEO of Electroflow, told TechCrunch. “If we want to have a chance of competing, we’ve got to flip that script.”

McShane and co-founder Evan Gardner have developed a technology they think is capable of undercutting Chinese producers on cost by removing several steps in the production process. If they can deliver, they could reduce the cost of an LFP battery by as much as 20% while building a domestic supply chain.

“We looked at the whole process of mining, starting from the rock or the salt water and getting all the way to a lithium chemical. We were like … that’s like ten steps. That clearly is not the best way to do it.”

Companies have been chasing the dream of making lithium from brine for over a decade, but so far, the cost of the end product has far exceeded the cost of LFP powder from Chinese suppliers, which today is priced at around $4,000 per metric ton. The LFP powder available from domestic sources — ExxonMobil actually has a brine extraction operation underway in Alabama — costs three times as much, which obviously means there is not much of a market for it.

McShane claimed that once Electroflow reaches full-scale production, he expects the company will be able to produce LFP powder for at least 40 percent less than the Chinese producers and do it in the United States with no need to rely on Chinese companies for processing or refining. “In our V1 system — end of this year — our goal is to be about at $5,000 per [metric] ton production cost point, and we’re going to scale up and get this to less than $2,500 per [metric] ton,” he said.

The process developed by Electroflow takes just three steps to transform salty water into battery-grade LFP material. The startup recently proved the technology worked in a test scenario using brine extracted from a pipe at a geothermal site in California.

The Electroflow Process

The key to the Electroflow technology is a cell containing anodes that, when run in one direction, absorb lithium ions from brine. When operated in the opposite direction, they release those lithium ions into water containing carbonates. When both processes are finished, the result is lithium carbonate that is ready to be reacted with phosphate, iron, and other reagents to produce LFP powder that is ready for shipment to a battery factory. For manufacturers who want to make something other than LFP, Electroflow can stop the process early and just send them lithium carbonate.

The system runs entirely on electricity, and not very much of it either. Some of the electricity used in the process is stored onsite in LFP batteries — a happy circumstance. McShane said producing 50 metric tons of lithium carbonate per year would require only as much electricity as would typically be used by an average US household.

The water used in the carbonate step can mostly be recycled — a major plus in an industrial process that often requires copious amounts of fresh water. “We don’t use a ton of electricity. We don’t use a ton of water,” McShane said. When the full size system is complete, it will be packaged inside a standard 20 foot shipping container and be capable of generating 100 metric tons of LFP material per year.

“We’re going to churn out these electrochemical cell stacks and really be able to process a lot of brine across the US,” McShane said. He’s confident the company will be able to undercut Chinese producers in a few years when Electroflow reaches commercial production. “Unless methods in China change to be a complete blank slate, clean sheet solution like we’re doing, they can’t get much lower than this,” he claimed.

Both McShane and Gardner were previously engaged in battery and battery materials research. “We just were really fascinated by the idea of using newer technology, like battery technology, and applying it to other industries beyond batteries. Applying battery tech to mining, turns out, is really fruitful,” McShane said.

Inspiration Is Where You Find It

But the true inspiration for Electroflow came to Gardner one day when he was riding Caltrain to work in the Bay Area. As people were getting on and off the trains from the platforms, he pictured them like ions moving between different chambers of a device. “He sketched it out on a piece of paper and brought it over to me,” McShane recalled. “I was like, oh man, that actually works.”

TechCrunch is reporting exclusively that Electroflow recently raised $10 million in a seed money funding round led by Union Square Ventures and Voyager with participation from Fifty Years and Harpoon Ventures.

It is hard to imagine that a couple of battery researchers could invent a totally new process for making LFP powder that no one else had ever thought of based on watching commuters shuttle in and out of a commuter rail station. But such “Ah, hah!” moments are well known in many industries, when a flash of inspiration suddenly changes the course of history.

No doubt, some very clever people in China and elsewhere are trying to understand what McShane and Gardner have done. Being an early leader in a new field is exciting, but it is often hard to maintain that first mover advantage. A domestic supply of affordable LFP powder would be wonderful news for EV manufacturers and the energy storage industry — assuming the administration doesn’t put the kibosh on the young company in some way.

Sign up for CleanTechnica’s Weekly Substack for Zach and Scott’s in-depth analyses and high level summaries, sign up for our daily newsletter, and follow us on Google News!

Sign up for CleanTechnica’s Weekly Substack for Zach and Scott’s in-depth analyses and high level summaries, sign up for our daily newsletter, and follow us on Google News!

Have a tip for CleanTechnica? Want to advertise? Want to suggest a guest for our CleanTech Talk podcast? Contact us here.

Sign up for our daily newsletter for 15 new cleantech stories a day. Or sign up for our weekly one on top stories of the week if daily is too frequent.

CleanTechnica uses affiliate links. See our policy here.

CleanTechnica’s Comment Policy