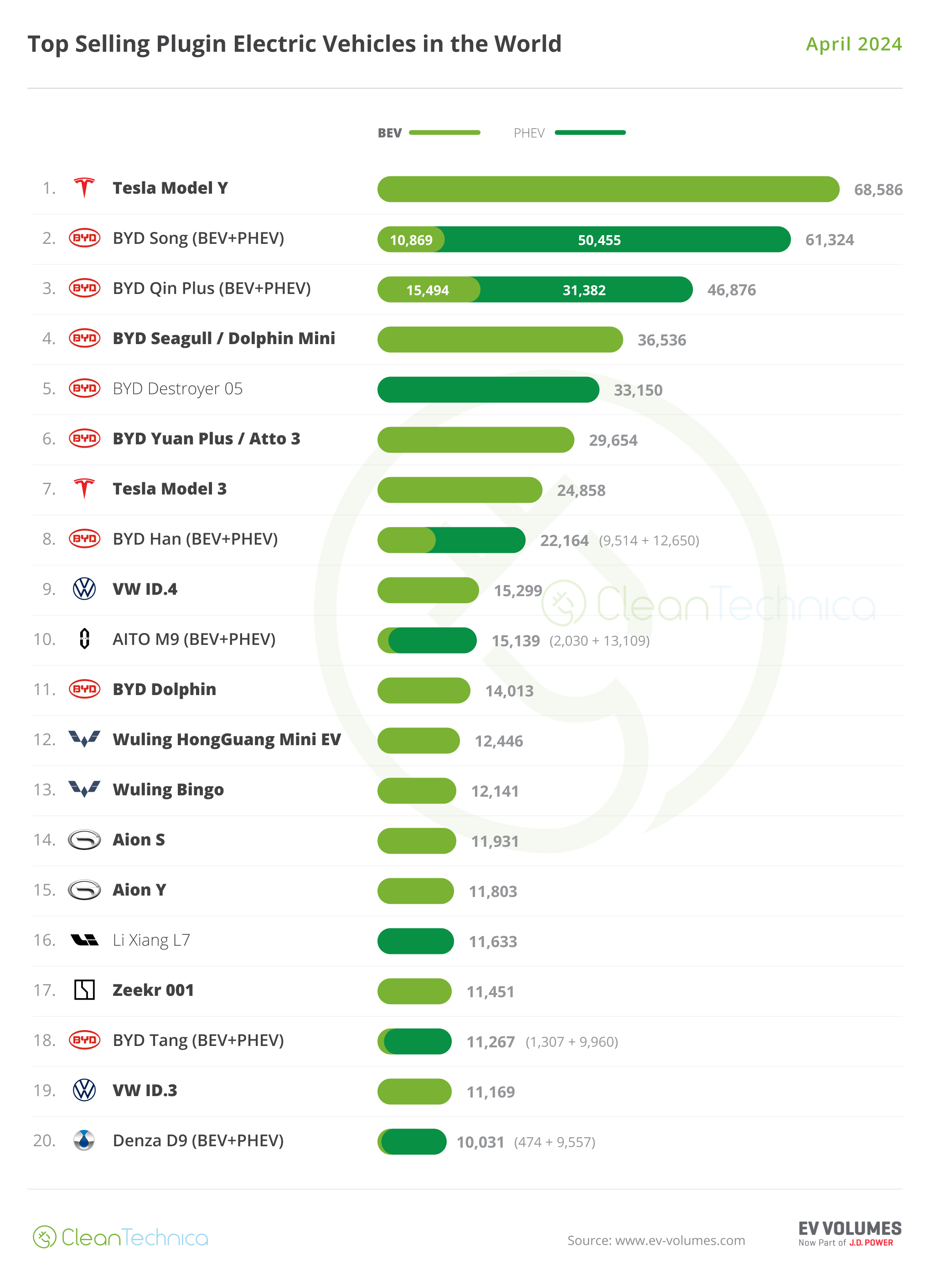

Jupiter Mines is already the largest manganese miner on the ASX, and the company is now kickstarting an exciting new venture.

While manganese has long been a critical ingredient in the steelmaking process, the commodity has taken on a much larger role in recent years.

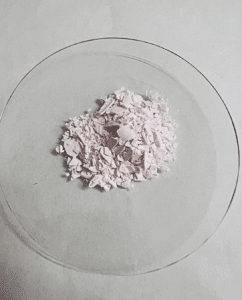

This boost in significance is driven by the growth of the electric vehicle (EV) market, which requires high-purity manganese sulfate monohydrate (HPMSM) to produce the batteries that power an EV.

According to Benchmark Mineral Intelligence, the battery demand for manganese is set to grow eight-fold this decade, from about 53,000 tonnes in 2020 to 459,000 tonnes in 2030.

This growth won’t just be driven by nickel-cobalt-manganese (NCM) batteries, but also by emerging lithium-manganese-iron-phosphate (LMFP) and lithium-manganese-nickel-oxide (LMNO) chemistries.

Image: Jupiter Mines

The battery market is not only growing but broadening, and EV manufacturers are increasingly turning to manganese-rich chemistries due to their ability to improve performance at a lower cost.

As the fifth most abundant metal in the Earth’s crust, manganese is also more readily available than other battery minerals such as cobalt and nickel.

So what does this mean for an established manganese producer like Jupiter Mines?

With a 49.9 per cent interest in the Tier 1 Tshipi manganese mine in South Africa, Jupiter not only has a producing asset with 120 years of production ahead of it, but also ore stockpiles at the right grade to feed a HPMSM processing plant.

“Jupiter already has access to what we call low-grade ore, which is by-product material produced through the normal production process at Tshipi,” Jupiter managing director and chief executive officer Brad Rogers told Australian Mining.

“Tshipi produces 37-per-cent manganese which is sold into the steel market – that makes up almost all of the revenue today.

“In processing the 37-per-cent material, Tshipi screens off 32-per-cent manganese and stockpiles it, because that material can’t be sold valuably into the steel market in most price environments.

“So we’ve got about two million tonnes of 32-per-cent manganese sitting on a stockpile which is well suited to conversion to battery-grade manganese and for the processing facility we’ve identified in our scoping study.”

A HPMSM scoping study Jupiter released in mid-March demonstrated the potential to produce 50,000 tonnes per annum (tpa) of HPMSM across an initial three years. This would increase to 100,000tpa from 2030.

Base case assumptions suggest a post-tax internal rate of return of 25 per cent and an earnings before interest, taxes, depreciation, and amortisation of $US179 million at full-scale production.

Jupiter would feed manganese from its Tshipi mine into a HPMSM downstream processing plant in North America which has an initial capital expenditure (capex) of $US430 million. Jupiter said this capex is in line with other advanced projects.

In completing the scoping study, Jupiter considered “the world of possibilities” that come with commercialising a battery-grade product.

Image: Jupiter Mines

“The scoping study weighed up a number of factors,” Rogers said. “Where are the customers going to be? What are the logistics from South Africa in terms of cost? What’s the cost and availability of inputs, such as sulphur, energy and other reagents?”

Rogers said it was also important to consider the downstream logistics, such as land availability for a HPMSM plant and the transportation distances and associated costs that come with delivering a finished HPMSM product.

Jupiter’s evaluations led it to North America, which is one of the world’s most favourable battery and EV jurisdictions.

“The US is the most advanced country when it comes to the availability of support for clean-energy projects at both a federal and state level,” Rogers said.

“There are other jurisdictions making efforts in this space, which could change the location of the plant in our base case scenario, but the IRA (Inflation Reduction Act) and state level support in relation to tax incentives and availability of land and permitting points us to various locations in North America.”

With the scoping study proving the economic viability of the HPMSM project, Jupiter Mines will now complete a pre-feasibility study (PFS) to further understand the scope of the venture. Jupiter hopes to complete this process by early 2025.

In preparing the PFS, Jupiter will engage an established engineering, procurement and construction management (EPCM) firm. Such a partnership will be an important springboard for the HPMSM project.

“As we move into stages where we will be looking to bring in partners, it’s helpful to have a recognised EPCM name that is leading that study,” Rogers said.

“The EPCM firm will assist us to refine our engineering work and we will then build a lab-scale pilot plant to produce enough material to share with customers.”

Rogers said it’s then important for Jupiter to begin signing offtake agreements.

“One of the most important pieces of work as part of the PFS phase is for us to establish customer offtakes,” he said. “These are new markets, so the most important thing anyone, including us, can do is have price and volume underwritten.

“While we’ve done a lot of our own first-principles work and the consensus is that there’s going to be a shortage of battery-grade manganese supply, the rubber hits the road in this phase where we establish term sheets with the car manufacturers and battery makers that we’ve already been talking to for the last year under non-disclosure agreements.”

Image: Jupiter Mines

By the end of the PFS phase, Jupiter Mines will hope to establish offtake pricing and volume for a period of time that underwrites the 4.3-year payback period of the HPMSM project.

The ideal agreements, Rogers said, would extend for at least five years.

“These are new markets and they’re going to go through levels of unpredictability as they grow, so I don’t think it’s sensible to take market risk,” he said.

Jupiter also wants to understand the scope of the project’s funding model by the end of the PFS. This will ideally be underpinned by Jupiter’s own finances, partner funding through offtake, debt and equity avenues, and grant funding.

“At the end of the PFS phase, it’s important that we have a higher degree of confidence in the project’s revenue potential through offtake as well as its funding potential,” Rogers said. “Then we can proceed to the next stage and spend more money on the project.”

When combining the strength of the battery-grade manganese outlook with the Tshipi mine’s long-term, right-grade and low-cost production profile, Jupiter has every chance to establish a HPMSM operation.

And with a HPMSM supply deficit likely to start from 2026, the miner has timed its run well to capitalise on a potential market shortfall.

This feature appeared in the June 2024 issue of Australian Mining.