Due to our fascination with computers, social networks, and intellectual capital, we seem to have lost our connection with real, tangible goods, that starts with materials dug up or farmed. With skilled labor, these materials are transformed into goods, or foods, thus creating a value chain that provides income for workers involved in every step of their creation. This value chain is the only way to create new wealth.

But the consumer doesn’t see this value chain; all they see is the finished product. Rare is the cell phone user who has a full appreciation of all the metals that went into their phone, including copper, tellurium, lithium, cobalt, manganese and tungsten.

Many people view of mining as dirty, dangerous, polluting and better done someplace else. While the industry has certainly done its fair share of harms, I’m here to tell you that the world simply cannot function without it.

Minerals are essential components of cars, energy plants, solar panels, wind turbines, fertilizers, machinery and building construction.

The mining industry is the starting point of a value chain that starts with resource extraction and ends with the sale of countless end products. The mining and metals industry moves a $1 trillion economy.

Among the forces that drive mining are population growth, income growth and urbanization, all of which increase the need for minerals.

According to the United Nations, the world’s population is expected to reach 9.7 billion by the year 2050 and 10.9 billion by 2100.

Some think that technology will eventually find substitutes for metals. If only it were so easy. According to a Yale study that evaluated metals used in various consumer products, “not one metal has an ‘exemplary’ substitute for all its major uses,” and for some of them a substitute for each of its primary uses does not exist at all, or is inadequate.

Mining is the economic foundation for a number of countries especially in the developing world. The International Council on Mining and Metals found at least 70 countries are extremely dependent on the mining industry, with mining accounting for up to 90% of foreign direct investment in low-middle income countries.

In these places, mining employment literally puts food on the table.

The global shift from a world run on fossil fuels, to one powered by renewable energies and electrification, means an even greater need for the minerals that go into these new technologies.

The World Bank projects the need for a 500 percent increase in graphite, cobalt, and lithium production by 2050. In 2022, one estimate claimed that approximately 700 million metric tons of copper would be needed over the next 22 years to reach sustainable economic growth targets—roughly the equivalent to what has been mined over the past 5,000 years of human history. Still other projections find that more than 300 new mines extracting critical minerals will be needed by the year 2030 to prevent a crippling supply shortage…

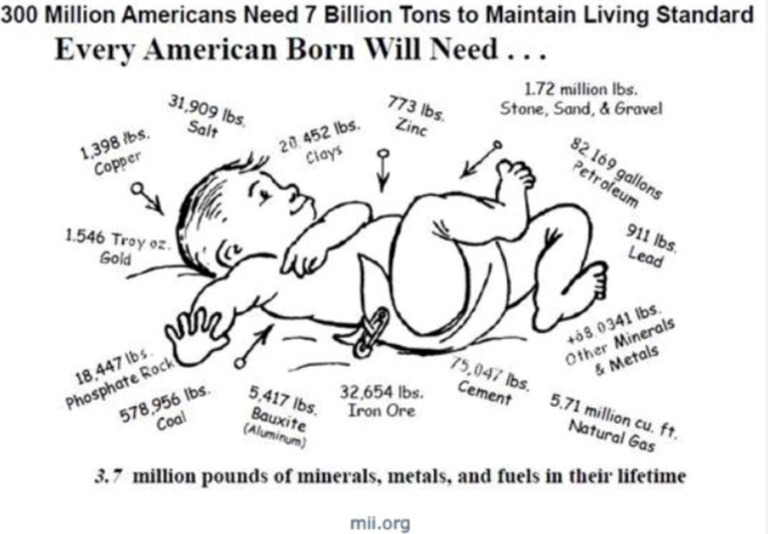

[T]he transition to clean energy is inextricably linked to a renaissance in mining, and more broadly, a renewed focus on the entire mineral supply chain. Indeed, virtually every technology seen as critical to the green revolution, from electric vehicles (EVs) to solar and wind power, demand far greater inputs of minerals and metals than traditional carbon-intensive methods. In the United States, the average American is already estimated to consume around three million pounds of minerals, metals, and fuels over their lifetime, a number which will in all likelihood increase as the energy transition continues to accelerate. — Center for Strategic & International Studies, ‘The Indispensable Industry: Mining’s Role in the Energy Transition and the Americas’

Critical minerals and the new economy

Included on the US Geological Survey’s list of 35 critical minerals are the building blocks of the new electrified economy, including lithium, graphite, and now copper.

According to a recent report by Bloomberg New Energy Finance, spending on the clean-energy transition surged 17% last year to a record $1.8 trillion. The total includes renewable energy investments, the purchase of electric vehicles, and the construction of hydrogen production systems. Add the investments in building out clean-energy supply chains, and $900 billion in financing, and the total funding in 2023 reached about $2.8 trillion.

The record spending reflects the growing urgency to fight climate change. Last year was the hottest year on record and 2024 could be even worse, fueled by now-continuous global warming and the El Nino climate phenomenon. BNEF says the world needs to invest more than twice the $1.8 billion to reach net-zero emissions by mid-century.

While 2023 was a challenge for many mineral commodities, mostly due to less demand from China, and the unsubstantiated threat of a recession, 2024 could see an improvement.

Jeff Currie, who spearheaded commodities research at Goldman Sachs for almost three decades, and correctly predicted the China-driven commodities boom of the 2000s, is bullish on the sector.

In an interview with Bloomberg Television, the veteran analyst said demand is at record levels, inventories are low and spare production capacity is largely exhausted.

“The set up for all of these markets is better than it was last year,” and if central banks proceed with interest rate cuts “you’re teeing yourself up for a fantastic 2024,” Currie said. “This is just classic ‘own commodities.’”

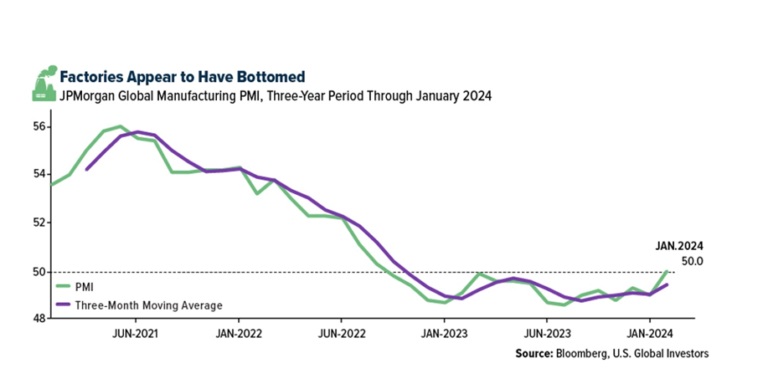

Another bullish signal for commodities is the recent uptick in manufacturing activity. The JP Morgan Global Manufacturing PMI hit 50 in January, stopping a 16-month streak of sub-50 ratings. Any number below 50 indicates an economic contraction.

In a column, Frank Holmes of U.S. Global Investors points out that US manufacturers kicked off the year with renewed optimism and an uptick in demand. The S&P Global US Manufacturing PMI climbed to 50.7 in January, its highest level since September 2022. This positive shift was attributed to easing inflation and more accommodating financial conditions, alongside an increase in production and payroll numbers.

Junior Resource Co

A junior resource company’s place in the food chain is to acquire projects, make discoveries and hopefully advance them to the point when a larger mining company takes it over. Discoveries won’t be made if juniors aren’t out in the bush looking at rocks.

Indeed juniors have one of the toughest jobs in the industry. Finding and advancing new projects is difficult and capital-intensive. The kicker is the juniors have no revenue stream to finance their exploration activities; they typically rely on outside sources for funding.

Investing early in the development cycle of the right gold junior, one that has an excellent project in a safe jurisdiction led by experienced management with the ability to raise money, can reap huge rewards — 5, 10, even 20 times your money isn’t uncommon.

At the beginning, these companies are often financed by accredited investors who buy shares in private placements. The junior then tries to advance its project, beginning with prospecting, through to drilling and completing economic assessments and feasibility studies.

Few exploration companies have the money or technical expertise to “go mining”. (A study in Australia found the riskiest activity a junior explorer can do is to actually build the mine. 28% of the New South Wales juniors in the study did this, and of those, went broke or closed down their operations. Another 25% were taken over.)

For many, the goal is to hit upon a deposit that’s good enough to attract a major who will acquire the asset. Another pathway is for the junior to partner with a larger company. An option or joint venture (JV) agreement is a way for juniors to gain access to the financial and technical resources needed to build the mine.

Back to junior mining’s place in the food chain, juniors are extremely important to major mining companies because they are the firms finding the deposits that will become the next mines. In this way, juniors help the majors to replace the ore that they are constantly depleting in their operating mines.

One source points out that senior miners have been allocating a relatively small portion of their revenues to exploration spending, with most expenditures invested in developing existing mines and measures to reduce operating costs.

If the seniors aren’t exploring, again, it falls to the juniors. But junior mining financing has pretty much dried up; global exploration budgets in 2021 were half of what they were in 2012.

Capital expenditures in mining fell from approximately $260 billion in 2012 to $130 billion in 2020 (corresponding to 15% and 8% of industry revenues, respectively), McKinsey & Company found.

One of the biggest challenges facing the mining industry is a growing skills gap created by an aging workforce and a dearth of talent waiting next in line.

Part of the problem has to do with declining enrolment in post-secondary programs related to mining, engineering, and extractive metallurgy. The other issue is mining itself, not considered an aspirational industry by younger people raised on environmental awareness and a different set of work values.

Money industry dogged by retirements and lack of new recruits

Institutional investors such as large banks and hedge funds used to invest in small mining companies, but many have exited the sector in pursuit of less risky propositions. The retail investor has all but fled the industry, due to losses incurred from the last downturn or aging out of the space. The younger investors replacing them have no knowledge of how to make money in junior mining, they don’t “get” gold, or they invest in sectors they understand, like tech and cryptocurrencies.

Conclusion

Mining is seen by some as a necessary evil whose environmentally destructive practices should be stopped, or at least, shouldn’t take place anywhere near them. They don’t realize or care that without mining, there would be no modern society: no steel to make bridges, no copper wiring that powers homes and businesses, no uranium to fuel nuclear reactors, no jewelry, no rare earths to make smart phones, solar panels, color monitors and TVs.

The reality is that mining oil and gas production is necessary and here to stay. As technology moves forward, the need for metals and the impetus for mining grows stronger, not weaker.

Despite being at the bottom of the mining food chain, junior resource companies perform an essential function: they find and develop the world’s future mineral deposits.

Juniors help the majors to replace the ore that they are constantly depleting in their operating mines, thereby helping to overcome the supply shortfall that is coming for several metals.

Richard (Rick) Mills

aheadoftheherd.com

subscribe to my free newsletter

*********