Sign up for daily news updates from CleanTechnica on email. Or follow us on Google News!

The 2024 hurricane season in the US officially began on June 1, and with it comes the annual prediction derby in which various organizations vie with each other to see who can come closest to the total number of hurricanes this year, which won’t be known until the season officially ends on November 30, 2024. Bloomberg says the first scientific attempt to predict how many Atlantic hurricanes would occur in a given year happened in 1984. The late scientist Bill Gray and his students at Colorado State University believed they could tease a signal out of water temperatures, weather patterns, and weather patterns in other parts of the world to produce a forecast of how many storms would form in the Atlantic from June through November.

In that first forecast, Gray and his team called for 10 named storms, with 7 becoming hurricanes. The season produced 11 storms and 4 hurricanes, showing that prediction was indeed possible. That opened the gates for others. AccuWeather jumped in during the early 1990s and the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration rolled its forecast out in 1998. This year, NOAA is predicting 17 to 25 cyclones (the generic name for tropical storms and hurricanes). Colorado State University has forecast 25, the UK Met Office puts the number at 22, and AccuWeather predicts 20 to 25. It’s even possible 2024 will match 2020, when a record 30 storms were named.

The number of Atlantic storms has been rising so far this century, partly because detection is much better than it was, but also because climate change is helping drive ocean temperatures higher. The world’s oceans are currently experiencing their second longest record heat streak, and this hot water can turn a mild storm into a town-flattening monster, writes Bloomberg’s climate reporter Brian Sullivan, who adds, “Our warmer world means the air can hold more moisture and that more of that moisture can fall as rain. So storms that make landfall have increasing potential to leave a deadly path of misery, and even mild tropical storms now come with a higher risk of severe flooding.”

Sullivan points out that whether a hurricane is a Category 1 or Category 5 makes little difference to those in its path. “Even small ones bring pain and misery. While the Atlantic is currently quiet and there’s only one tropical storm spinning harmlessly through the North Pacific right now, I take no solace in that. All indications are that 2024 could be a terrible year.”

A Double Whammy Of Heat & Humidity

Warmer air holds more moisture, a fact not even the learned solons at Faux News can dispute. Not only are hurricanes more powerful, the are dumping heavier rain because of the extra moisture in the air. Compounding the damage hurricanes do is the fact they are moving more slowly than in the past, which means the heavy rain continues longer, which greatly increases the risk of flooding. The final factor that makes today’s hurricanes more dangerous is that humans, in their infinite wisdom, have made their cities out of impermeable materials like asphalt and concrete while making little to no provisions to manage all that stormwater. As a result, while wind damage from a hurricane can be significant, we are seeing more and more damage from flooding, such as what happened to the west coast of Florida after Hurricane Ian in 2022.

Mikhail Chester, director of the Metis Center for Infrastructure and Sustainable Engineering at Arizona State University, tells the New York Times that what happened in Houston a few days ago, when powerful storms left a million people without electricity, was the “Hurricane Katrina of heat.” In his scenario, extreme heat and a power failure in a major city like Houston could lead to a series of cascading failures, exposing vulnerabilities in the infrastructure that are difficult to foresee and could result in thousands, or even tens of thousands, of deaths from heat exposure in a matter of days. The risk to people in cities would be higher because all the concrete and asphalt amplifies the heat, pushing midday temperatures as much as 15 degrees to 20 degrees higher than surrounding vegetated areas.

One of the most dangerous illusions of the climate crisis is that the technology of modern life makes us invincible, Jeff Goodell writes in the New York Times. Humans are smart. We have tools. It will be expensive but we can adapt to whatever comes our way. As for the coral reefs that bleach in the hot oceans and the howler monkeys that fell dead out of trees during a recent heat wave in Mexico, well, that’s sad but life goes on.

The 3HEAT Study

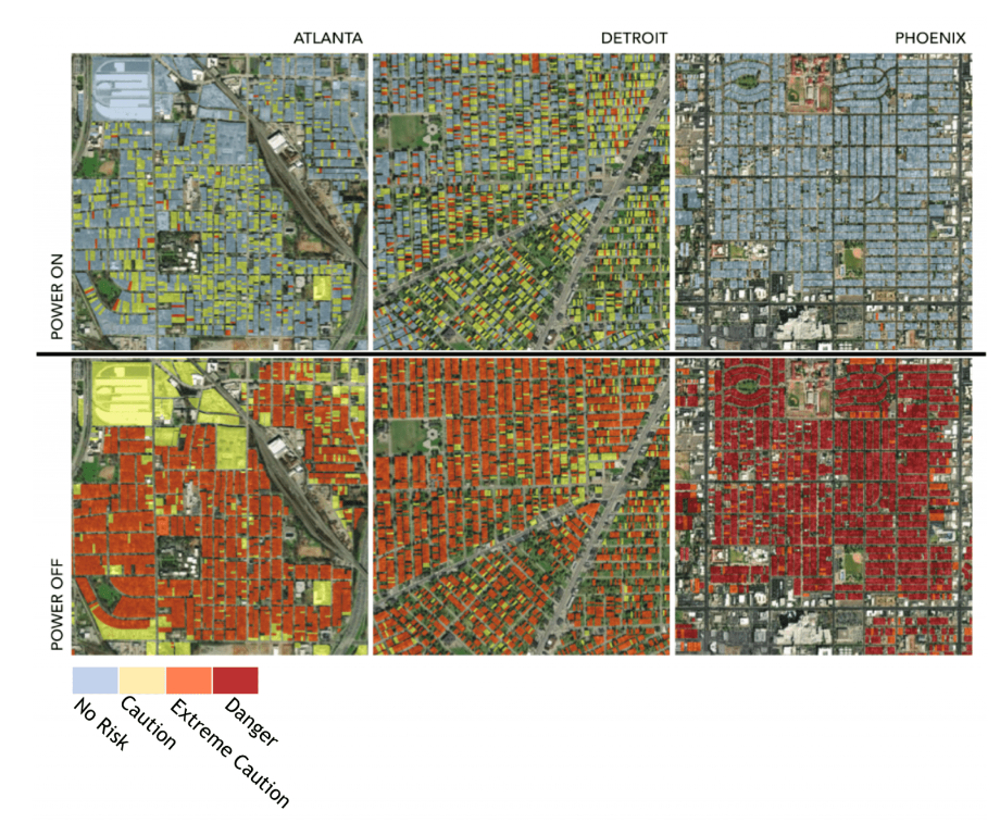

Goodell points out that more than 750 million people in the world have no access to electricity, much less air conditioning. He says the bubble of invincibility that surrounds people in US “is far more fragile than we know.” Last year, researchers at Georgia Institute of Technology, Arizona State University and the University of Michigan published a study looking at the consequences of a major blackout during an extreme heat wave in three cities: Phoenix, Detroit, and Atlanta. In the study, the cause of the blackout was unspecified.

“It doesn’t really matter if the blackout is the result of a cyber attack or a hurricane,” said Brian Stone, the director of the Urban Climate Lab at Georgia Tech and the lead author on the study. “For the purposes of our research, the effect is the same.” Whatever the cause, the study noted that the number of major blackouts in U.S. more than doubled between 2015-16 and 2020-21. Stone and his colleagues focused on those three American cities because they have different demographics, climates and dependence on air conditioning. In Detroit, 53% of buildings have central air conditioning; in Atlanta, 94%; in Phoenix, 99%. The researchers modeled the health consequences for residents in a two-day citywide blackout during a heat wave, with electricity gradually restored over the next three days.

The results were shocking: in Phoenix, about 800,000 people — roughly half the population — would need emergency medical treatment for heat stroke and other illnesses. The flood of people seeking care would overwhelm the city’s hospitals. More than 13,000 people would die. Under the same scenario in Atlanta, researchers found there would be 12,540 visits to emergency rooms. Six people would die. In Detroit, which has a higher percentage of older residents and a higher poverty rate than those other cities, 221 people would die. The researchers found the much larger death toll in Phoenix was explained by two factors. First, the temperatures modeled during a heat wave in Phoenix (90 to 113 degrees) were much higher than the temperatures in Atlanta (77 to 97 degrees) or Detroit (72 to 95 degrees). And second, the greater availability of air conditioning in Phoenix means the risks from a power failure during a heat wave are much higher.

Perhaps we should not be surprised by these number, Goodell says. Researchers estimate 61,672 people died in Europe from heat-related deaths in the summer of 2022, the hottest season on record on the continent at the time. In June of 2021, a heat wave resulted in nearly 900 excess deaths in the Pacific Northwest. And in 2010, an estimated 56,000 Russians died during a record summer heat wave. The hotter it gets, the more difficult it is for our bodies to cope, raising the risk of heat stroke and other heat illnesses. And it is getting hotter across the planet. Last year was the warmest year on record, and the 10 hottest years have all occurred in the last decade.

De-Risking Hurricanes & Heat

There are many paths available to communities to reduce the combined risks of hurricanes and excessive heat. Building cities with less concrete and asphalt and more parks and trees and access to rivers and lakes would help. So would a more sophisticated nationally standardized heat wave warning system. Major cities also need to identify the most vulnerable residents and develop targeted emergency response plans and long-term heat management plans. Making the grid itself more resilient is equally important. Better digital firewalls at grid operation centers thwart hacker intrusions. Burying transmission lines protects them from storms. Batteries to store electricity for emergencies are increasingly inexpensive.

But the hotter it gets, the more vulnerable the grid becomes, even as demand for electricity spikes because customers are running their air conditioning all the time. Transmission lines sag, transformers explode, power plants fail. One 2016 study found the potential for cascading grid failures across Arizona to increase 30-fold in response to a 1.8ºC rise in summer temperatures.

“Most of the problems with the grid on hot days come from breakdowns at power plants or on the grid caused by the heat itself, or from the difficulty of meeting high demand for cooling,” Doug Lewin, a grid expert and author of the Texas Energy and Power newsletter, told Goodell. The best way to fix that, he said, is to encourage people to reduce power demand in their homes by installing high efficiency heat pumps, better insulation, and smart thermostats. Oh, here’s a suggestion that will gladden the hearts of CleanTechnica readers. Lewin advocates for people to generate their own power with solar panels and battery storage, an idea that most investor-owned utilities strongly dislike.

Old Ideas Are Still Effective

The looming threat of a “heat Katrina” is a reminder of how technological progress creates new risks even as it solves old ones. On a brutally hot day during a recent trip to Jaipur, India, Jeff Goodell visited an 18th century building that had an indoor fountain, thick walls, and a ventilation system designed to channel the wind through each room. There was no air conditioning, but the building was as cool and comfortable as a new office tower in Houston, he says.

Air conditioning may indeed be a modern necessity that many of us who live in hot parts of the world can’t survive without, but it is also a technology of forgetting, he argues. Once upon a time, people understood the dangers of extreme heat and designed ways to live with it. “Now as temperatures rise as a result of our hellbent consumption of fossil fuels, tens of thousands of lives may depend on remembering how that was done. Or finding better ways to do it,” he says.

The Takeaway

There are several lessons we can draw from all this. One, more powerful storms are occurring more often. Two, we have made ourselves dependent on air conditioning to manage higher average temperatures. Three, we may have built not a modern society but a technology-inspired prison that will trap many in scenarios where extreme heat threatens their very existence. Four, we have forgotten things we knew decades or centuries ago that could help us weather what Mother Nature has in store.

Those things include not building cities with impervious materials, especially in flood plains. Another is not building cities and vacation homes on the edge of oceans. A study in 2018 put the possible damage to Miami from a powerful hurricane at $1.3 trillion. Since then, Miami has added a hundred or more towering structures to its skyline. Boosting local generation and storage of electricity should be a priority. And of course the elephant in the room is the continued use of fossil fuels, which add to the impending climate crises with every passing hour.

As Al Gore told us, climate change is a human-made phenomenon. That may be an inconvenience for many, but nothing like the ultimate inconvenience of dying prematurely. We really do need to accelerate the transition away from fossil fuels, if not for our own sake but for the sake of our children and their children and the children after that. As Samuel Beckett might say, “We might as well get on with it.”

Have a tip for CleanTechnica? Want to advertise? Want to suggest a guest for our CleanTech Talk podcast? Contact us here.

Latest CleanTechnica.TV Videos

CleanTechnica uses affiliate links. See our policy here.

_Logo_Color.jpg)