Support CleanTechnica’s work through a Substack subscription or on Stripe.

General Motors’ decision to end development of its next generation Hydrotec fuel cells for vehicles did not come as a surprise. It marked the close of a long, careful experiment. After years of research, pilot programs, and cautious optimism, GM finally acknowledged what the energy math had been showing for years. Hydrogen fuel cells are not a viable pathway for road transportation. They never were.

GM has been involved in hydrogen for decades. The Electrovan of 1966 is often remembered as the first hydrogen-powered vehicle ever built, a laboratory experiment on wheels that carried more hazard than hope. Over the years, GM continued to test the idea, producing concept vehicles and demonstration fleets, usually when policy winds or oil prices made alternative propulsion fashionable again. Each revival faded into dormancy as technical and economic barriers remained unchanged. Hydrogen fuel cells were light on emissions but heavy on cost, complexity, and infrastructure demands.

The Hydrotec era was meant to be different. GM had branded a new generation of modular fuel cell systems that could, in theory, be deployed across vehicles, locomotives, and generators. The company formed a joint venture with Honda to manufacture stacks in Michigan. It collaborated with Wabtec on fuel-cell locomotive concepts, although that depended on the next generation of Hydrotec fuel cells which will no longer exist, so they’ve quietly ended that pathway as well. It even tied up with Nikola Motors, a firm that claimed it would revolutionize trucking through hydrogen. That partnership evaporated when Nikola collapsed into bankruptcy, leaving behind lawsuits, debt, and empty promises. The promised fuel cell factory has been shelved.

The underlying problem was not fraud or poor management. It was physics. Converting electricity to hydrogen through electrolysis, compressing or liquefying it, transporting it, and then converting it back into electricity inside a vehicle stack wastes most of the original energy. The entire process typically returns less than one third of the energy put in. Battery electric systems, by contrast, can deliver about three quarters of grid energy to the wheels. When one system wastes twice as much energy as the other, economics eventually settle the argument.

GM framed its decision in practical terms. The company cited high costs, limited infrastructure, and low consumer demand. There are only about 60 hydrogen refueling stations in the United States compared to over 250,000 public fast-charging points for electric vehicles. That disparity is not an accident. The infrastructure follows the economics. Building hydrogen stations requires expensive compression, storage, and safety systems. Each site costs millions. Building EV charging sites requires copper wire and transformers. Consumers have already voted with their wallets, and regulators have aligned their policies with the market’s direction.

GM’s move also reflects a broader shift in the transport sector. Heavy trucks, once the supposed last refuge for hydrogen, are moving toward battery systems as megawatt-class charging becomes standardized, with deliveries shooting up globally in the first quarter of 2025 while hydrogen heavy truck sales halved. Companies such as Windrose and Volvo are deploying electric freight platforms that can recharge in less time than a driver’s mandatory rest period. Bus fleets are following the same trajectory, dropping hydrogen in favor of cheaper, simpler battery-electric models that can charge overnight in depots. Maritime and rail applications that once looked promising for hydrogen are being overtaken by direct electrification or battery hybridization.

The Wabtec collaboration sits at the edge of this retreat. When it was announced in 2021, the idea of a Hydrotec-powered locomotive carried symbolic weight. It represented a chance for hydrogen to find relevance outside of roads. Today, there is little sign of active progress. Wabtec’s more recent work has shifted toward dual-fuel hydrogen-diesel combustion engines, a transitional technology at best. Fuel cell locomotives remain an engineering curiosity without a commercial path. The infrastructure and fuel costs that doomed hydrogen cars are not gentler on railways.

Hydrogen’s collapse in transportation is not a failure of engineering talent. It is the predictable outcome of energy system realities. Batteries scale with volume and time. Their costs have fallen by an order of magnitude in a decade. Their manufacturing shares most of the supply chain with existing industrial and mining sectors. Hydrogen, in contrast, requires a parallel infrastructure built from scratch, with no shared foundation with current fuels or electricity networks. Every kilogram produced must be moved, compressed, or liquefied before it can be used. Every step adds cost and energy loss.

GM’s decision to keep producing fuel cells for stationary applications under its joint venture with Honda is not a sign of conviction, but a matter of inertia. The company is maintaining a foothold in a sector that looks viable only on paper. Stationary hydrogen fuel cells can power data centers or remote installations, but those niches are already being filled by batteries, grid interconnections, and conventional backup systems that are cheaper and easier to operate. Even in these controlled environments, hydrogen supply and storage remain expensive and inefficient. The market is too small to justify long-term investment, and the economics will only worsen as battery systems keep improving. Stationary fuel cells, like hydrogen transport, are an interesting technology with no enduring commercial role.

The reality is that hydrogen will remain what it has always been: a useful industrial molecule, not an energy vector. It is indispensable in ammonia production, hydrotreating vegetable oils for food and fuel, refining crude oil and certain chemical processes. In those sectors, it is a feedstock, not a fuel. The demand for hydrogen will persist although I project it will shrink substantially, and it will remained tied to manufacturing and materials, not mobility or grid energy. Electrolyzers producing green hydrogen will replace fossil-based production over time, but the molecule will stay inside factories and pipelines, not inside cars and trucks.

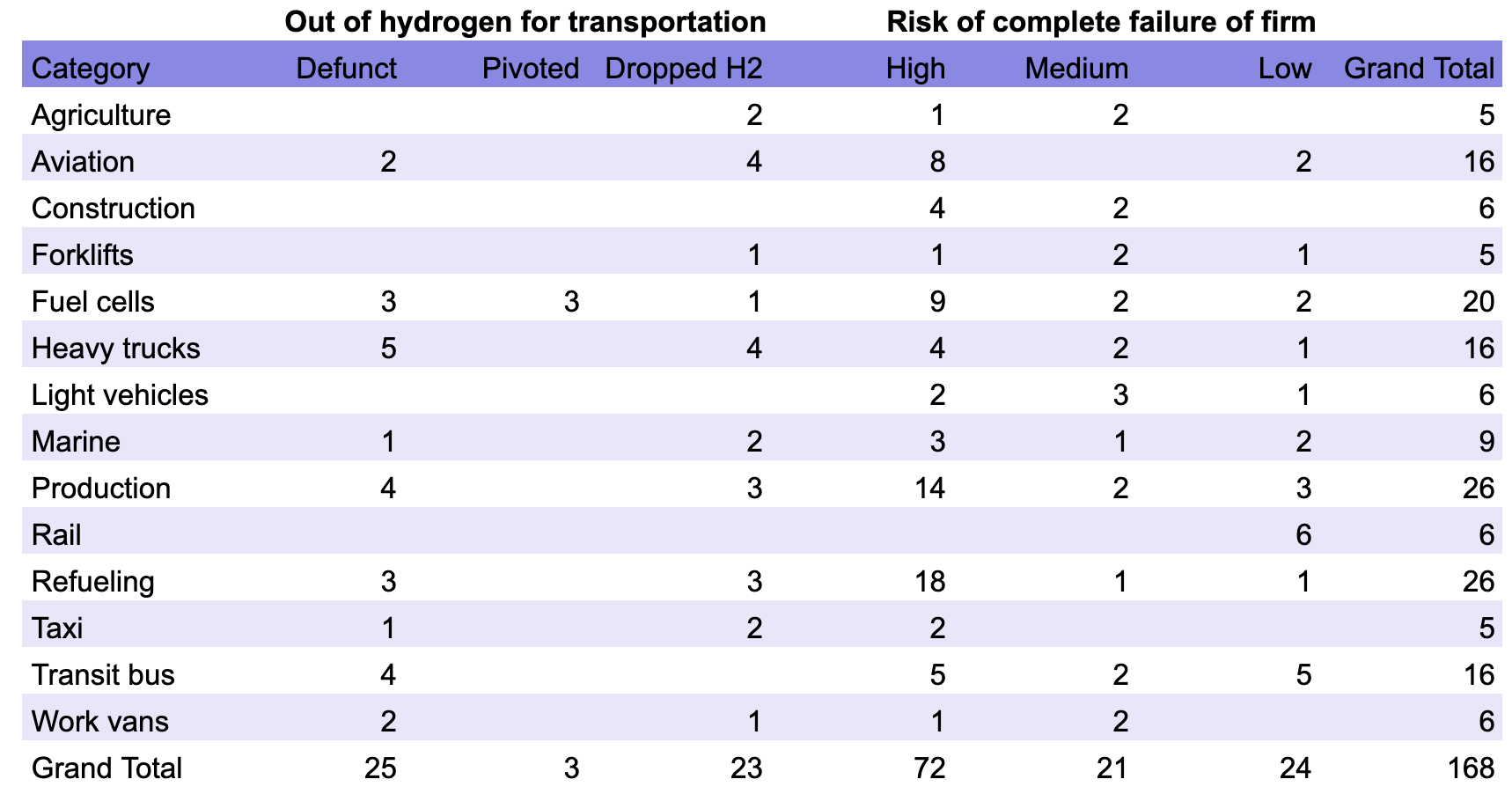

GM’s pivot away from hydrogen is part of a pattern, not an isolated choice. Dozens of companies, over 30% of firms that were engaged in hydrogen for transportation that I’ve been able to identify across every mode of transportation and portion of the value chain, that once positioned hydrogen as a transportation revolution have disappeared or refocused. The survivors are those that diversified early into batteries, charging, and renewable power, or for whom hydrogen was a minor portion of their offerings. Many of those that haven’t formally announced dropping hydrogen or pivoting out of transportation are undoubtedly doing just that, but even more quietly than GM. Hydrogen’s retreat is steady and rational. The technology found no mass market because the alternatives were simpler, cheaper, and more efficient.

Plug Power’s latest maneuver to stave off collapse—a so-called warrant inducement deal—offers a textbook example of how investors keep throwing good money after bad in the hydrogen mirage. The company convinced an anonymous backer to exercise old warrants at $2 per share, raising roughly $370 million in cash at the cost of issuing 185 million new shares. That bought Plug perhaps two more months of oxygen, depending on whether its cash burn holds near the $150–$230 million per quarter seen this year or it radically cuts expenditures, and also diluted existing share equity by about 30%. It did nothing to change the fundamentals: no profitable hydrogen business, no credible path to positive cash flow, and no market that can absorb its losses indefinitely. The temporary share-price bump reflected relief that the firm wouldn’t go under this quarter, not faith that it ever will succeed. Like every other hydrogen-for-energy play, this is just another expensive pause on the slow march toward inevitable bankruptcy.

This is not a story of disappointment or betrayal. It is a story of convergence. After decades of experimentation, the transportation industry is aligning around a single architecture: electric drive powered by electrons, not molecules. GM’s withdrawal from hydrogen vehicles closes a chapter that was always destined to end this way. The experiment ran its course, the data came in, and the conclusion is clear. Hydrogen belongs in the chemical plant, not on the road.

Sign up for CleanTechnica’s Weekly Substack for Zach and Scott’s in-depth analyses and high level summaries, sign up for our daily newsletter, and follow us on Google News!

Have a tip for CleanTechnica? Want to advertise? Want to suggest a guest for our CleanTech Talk podcast? Contact us here.

Sign up for our daily newsletter for 15 new cleantech stories a day. Or sign up for our weekly one on top stories of the week if daily is too frequent.

CleanTechnica uses affiliate links. See our policy here.

CleanTechnica’s Comment Policy