Sign up for daily news updates from CleanTechnica on email. Or follow us on Google News!

The job of Chairman and CEO of a global company comes with a few requirements. Being awake should be one of them. Since 2020, Farley has received $82 million for napping it seems. Before that he had executive vice president and leadership roles responsible for global marketing and sales back through 2010, also raking in the big bucks.

Late in 2023, Farley and his replacement chief operating officer — Farley held that job for a few months before ascending to the Master Bedroom — stretched, rubbed their eyes and flew to China on a junket undoubtedly intended to reinforce their rightful American exceptionalism. Unfortunately, reality threw a vat of ice water over them in the form of incredibly refined, competent and cheap electric cars, shocking them fully awake.

“John, this is an existential threat,” Farley told Ford board member and former Goldman Sachs executive John Thornton after his trip.

Yes, only in mid 2023 did the CEO and Chairman of Ford Motor Company, one of America’s most storied firms, realize that maybe the Chinese weren’t just doing cheap knockoffs of US products and happily buying US brand cars with the proceeds.

Presumably it took a year for this to become public because Farley’s sleeping pattern was so disrupted that he couldn’t concentrate. That would explain why electric vehicles were only 1.65% of Ford’s global sales in 2023, and still only a paltry 4.3% in the first half of 2024. Meanwhile, Tesla sold 25 times as many electric cars globally. BYD sold 41 times as many plug-in cars. While those two firms are the highest volume car, SUV and light truck OEMs, Ford has been outsold by 180 times in this space.

This isn’t news to me. In 2017 I published 6 of 10 Big Electric Car Companies Are in China, and my assessment of Ford was grim.

Ford is making some moves, but not at the scale of GM or VW and seems to be more responding to GM than anything else.

An assessment of the global electric vehicle market and Ford merited one lukewarm, brief sentence. At the time, Farley was the Executive Vice President and President of Global Markets. If that sounds like a job that would require paying close attention to China’s reality and increasing competitiveness, it is. If that sounds like a job that should understand disruptive innovation’s death knell for firms like Ford, it is. If that sounds like a job that should have been creating strategy to deal with the reality of China’s emerging electric vehicle juggernaut, it is.

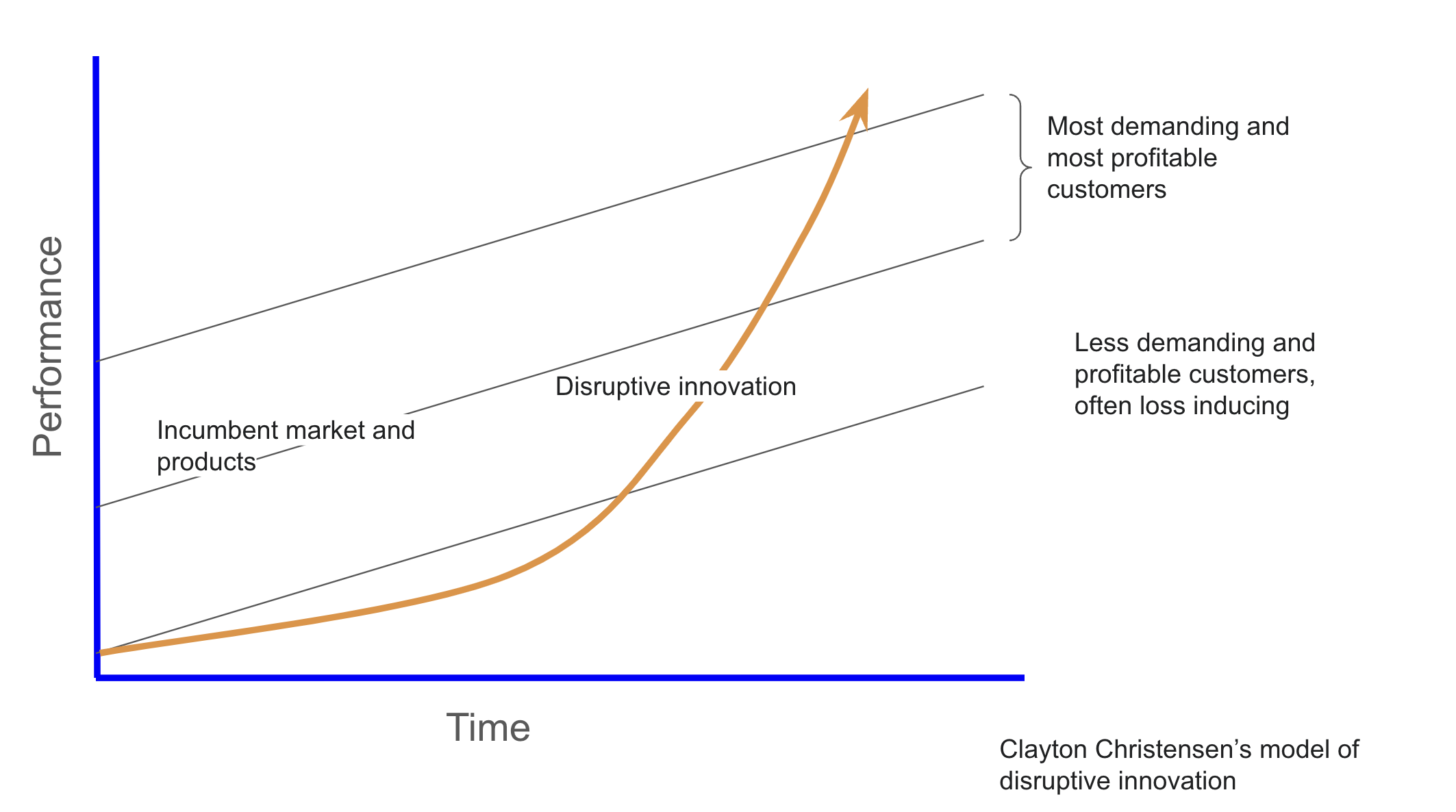

It’s worth going back to disruptive innovation. This is a fundamental market dynamic that Clayton Christensen documented at length in The Innovator’s Dilemma back in 1995, leveraging the insights from Richard Fosters’ work on innovation from the 1970s. This isn’t new stuff. This is basic b-school stuff. This is executive 101 stuff. This is stuff Farley should have been considering as a bread-and-butter concern from 2010 onward.

Disruptive innovation comes with nuances but it boils down to incumbents increasingly servicing their most demanding and profitable customers at the expense of their more numerous base. That base is eaten away by an innovative offering that doesn’t provide nearly the feature-rich products that the top end customers demand, but finds willing customers because it has a lower price point or greater convenience. In a lot of cases, the low-end market disruptor, because it has a superior technical or market pathway, creates products with the performance to eat the entire market, leaving the incumbent bankrupt.

Do you remember the first digital cameras? They sucked. I was an early adopter because they were convenient for capturing white boards — requiring multiple pictures because the resolution was low — and crappy snapshots of things. They were good enough for rapid documentation that could be put on a computer screen, but still lower resolution than the cardboard snapshot cameras that were fairly common around then.

Time passed. Kodak’s profits increased slightly as the snapshot brigade buying two rolls of the cheapest film and buying discount developing started using the first digital cameras. Camera store employees were able to spend more time with professionals and prosumers. Everyone was happy.

Then digital cameras started to eat not just Kodak’s snacks, but its breakfasts, lunches and dinners. Kodak was increasingly left only catering black tie events, turning from a mass market purveyor of the technology necessary for capturing lives and events into a boutique supplier to a dwindling market.

Once a giant in the photography industry, it has undergone significant transformation since its 2012 bankruptcy. Today Kodak focuses on commercial printing, advanced materials, and niche markets like motion picture film, an increasingly small market being displaced by digital cameras as well. Once synonymous with consumer photography, Kodak has shifted to areas such as high-speed inkjet printing, industrial materials, and even pharmaceuticals, with mixed success. Despite these pivots, Kodak has struggled financially. In 2020, Kodak reported revenues of $1.03 billion, a stark decline from its peak of nearly $16 billion in the late 1990s. Over the past few years, revenues have continued to fluctuate, with modest increases in some sectors but an overall struggle to maintain profitability in a highly competitive market.

That’s disruptive innovation, where a cheaper, more convenient technology with a great technical advancement opportunity destroyed an industry and the firms that couldn’t adapt fast enough.

The same process played out with industry giant Xerox and its photocopiers. Ricoh and Canon crushed it with initially crappy photocopiers that could be installed on a desk for anyone to use, not operated by trained experts in a locked room. Now the locked room is converted to storage and there are no photocopier operators receiving orders in office buildings anywhere in the world.

While it still offers print and digital document solutions, Xerox has expanded into areas like software, IT services, and digital transformation. The company now provides services in workplace automation, 3D printing, AI-driven solutions, and augmented reality for remote assistance. Xerox has also made moves into IT outsourcing and cybersecurity.

In recent years, Xerox’s revenue has continued to decline, a trend that has persisted for more than a decade. In 2019, Xerox generated $9 billion in revenue, but this dropped to around $7 billion in 2020, largely due to the COVID-19 pandemic, which significantly impacted demand for office equipment and services, and both were far off 2000’s $18.6 billion. While the company has been making efforts to transform and expand into new markets, its core printing business remains under pressure due to the ongoing digitization of workplaces and the decline in paper-based document management

The same story can be found in firm after firm which didn’t cannibalize its own markets to innovate into the future, but instead fell into the trap of dismissing new entrants and technologies. Arrogance writ large and often, so often that this is basic education for strategic executives. Apparently Farley was asleep in those classes as well.

It’s not like China was hiding its ambitions. Its strategic focus on the global electric vehicle market dates back to 2009 when the government launched the “Ten Cities, Thousand Vehicles” pilot program. This initiative was aimed at promoting electric and hybrid vehicle development across the country by providing subsidies to local manufacturers and encouraging public adoption of new energy vehicles. It marked a turning point, as the Chinese government recognized the potential of EVs to reduce oil dependency, curb pollution, and position China as a leader in a rapidly growing market.

Ford has been in the Chinese market since the 1980s, so it’s not like this should have been news to it or a surprise to the guy who has had global markets accountability since 2010.

What are the major components of an electric car? A car, batteries, lots of electronics and physical amenities. What has China been establishing core dominance of intentionally for decades? Batteries and electronics. What do its own increasingly affluent citizens demand in their cars? Smart phones on wheels with good range and luxurious appointments.

What do Ford’s core US customers — 45% of all Ford’s cars are sold in the country — want from Ford, at least according to Ford? Familiar brands, huge SUVs and pickups and less of that new-fangled app on wheels stuff. Look at their electric ‘cars’. A huge pickup and an SUV, both with familiar Ford brands, although the SUV has approaching zero in common with its namesake. Among other things, the original Mustang was under 50% of the average wage, while the new Mustang is about 75% of the average wage in the country. An extra three months’ salary for a car is a big jump, and that’s for a lower cost model, not the GT Performance Edition.

This is why my assumption has been that Farley has accidentally been Rumpelstiltskinning his way through the past decade, snoozing in the bed that must have come with the corner office. How in the world could any executive in the automotive industry be surprised by test driving Chinese cars in 2023, never mind someone with 15 years in global market roles? How could they have just realized that they were facing an existential threat?

The other alternative is that Farley is just incompetent to lead a great American company. Nah, must be narcolepsy.

Have a tip for CleanTechnica? Want to advertise? Want to suggest a guest for our CleanTech Talk podcast? Contact us here.

Latest CleanTechnica.TV Videos

CleanTechnica uses affiliate links. See our policy here.

CleanTechnica’s Comment Policy