Sign up for daily news updates from CleanTechnica on email. Or follow us on Google News!

A year ago I published an assessment of a quite remarkably bad, unpeer-reviewed paper by one of the Geological Survey of Finland’s (GTK) associate professors, Simon Michaux. The paper’s quite risible conclusions were that there wasn’t nearly enough metal in the ground to be able to electrify everything with renewables. Understandably, it was heavily amplified by the usual suspects.

It was bad enough that they hosted it on the GTK website at all instead of requiring him to put it on a crank pseudoscience blog site, but now GTK has actually published the two-part study in its purportedly peer-reviewed Bulletin, the house publication arm for GTK’s researchers. This is to be differentiated from their journal which others contribute to.

This, of course, means that they are lending their credibility more fully to this quite awful study. And it means that the credulous people who think both that any peer review means a study is credible and those who think that a bad paper appearing in a peer-reviewed journal means all peer review is terrible are both encouraged by this. Basically, it’s a quite remarkably bad idea for GTK.

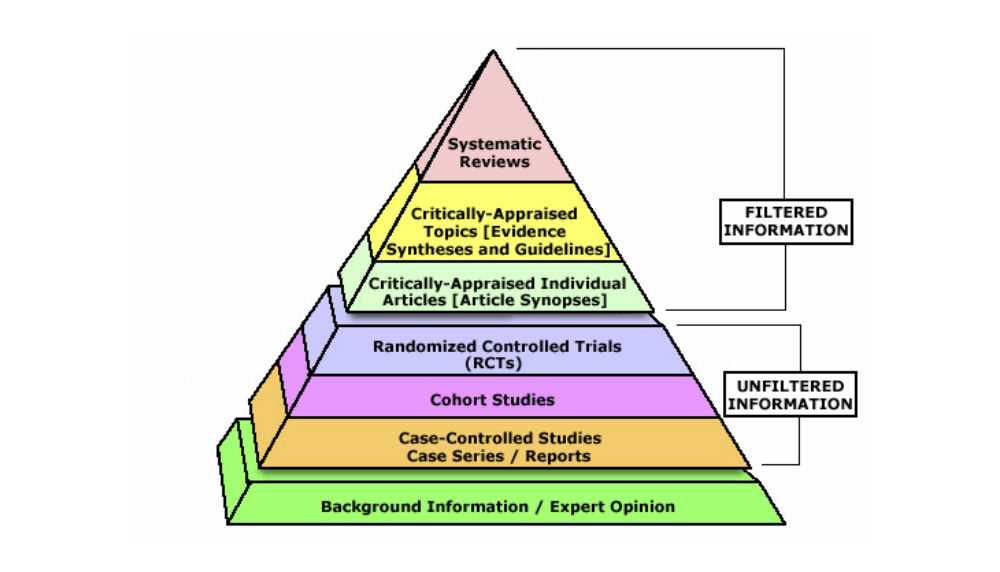

I’ve been leveraging this pyramid of reliability of published material for a long time. It was critical when considering the work I was doing in the 2000s related to building the world’s most sophisticated outbreak, communicable disease, and vaccination management system in the world in Canada in the aftermath of SARS, one that was used during COVID in Canada and the Middle East.

It was crucial as I considered all of the evidence concerning purported health impacts of wind energy, something public health experts like Simon Chapman, former Director of Public Health at the University of Sidney, and a regular collaborator of mine during that period, referred to as a communicated disease. The meaning of that phrase is that people became convinced they had what another remarkably bad, self-published study called “wind turbine syndrome” when they were told that wind energy was making them sick, getting more and more symptoms due to the nocebo effect.

And it’s crucial when considering something like Michaux’ material. His study is at the bottom of the hierarchy of evidence, the least reliable form of evidence that would appear in peer-reviewed publications. By contrast, the work of the UN IPCC reports that come out every few years are at the top of the hierarchy of evidence. They look at every piece of peer-reviewed information from the previous 5–7 years; assess whether it is credible enough to be included in the systematic review by clear, transparent, and published evaluation criteria; assess the degree of reliability of the various conclusions against other related conclusions; then synthesize a consensus position among the group doing the work.

To be clear, I don’t pretend that I’m doing anything other than providing expert opinion, and even then I don’t try to get into peer-reviewed journals and say in virtually every article, but especially my projections of the future, that I don’t claim to be right, merely less wrong than most. My work has risen to the status of gray literature — i.e., research and information that is produced outside of traditional commercial or academic publishing and distribution channels but yet is considered as credible enough to consider in industry and peer-reviewed reports in some cases.

Back to Michaux and the studies. There are two of them covering 275 pages in the most recent iteration. The first attempts to create a single energy model of the entire world covering all transportation modes, all industries, all forms of generation, all forms of storage, and all forms of fuels. It attempts to assess all forms of repowering and which ones will dominate. It does this without any prior publications by Michaux on the subject that are apparent. While I’ve covered the same ground, it’s been fifteen years of constant publication, refinement, disagreement, mistakes, and improvements. My work has been improved because experts have looked at it along the way and graciously granted me their insights.

The second paper then uses that entire, iconoclastic, untested model of a future projection to create a minerals forecast for the entire world for all forms of energy generation, storage, and use.

All this from a person whose academic and professional expertise is the dust created during explosions, specifically in the mining industry. He’s not a transportation researcher and has no prior publications in the space. He’s not an energy researcher and has no prior publications in the space. He’s not an agricultural or biofuels researcher and has no previous publications in the space. He’s not an industrial heat expert and has no previous publications in the space.

Frankly, this has all the hallmarks of an obsessive crank, not a study to be taken seriously, but Michaux takes it and himself very seriously. The Dunning Kruger is large in this one. To say that there are glaring problems with both papers is to equate glaring to the light of the sun from an orbit inside that of Mercury.

For example, did you know that from generation to end use of electricity the efficiency losses are 60%? That will surprise literally every energy modeler and grid researcher ever. According to Michaux’ study, they are.

Did you know that wind turbines and solar panels only last 20 years? That will surprise all of the people operating wind farms and solar farms with 30-year-old devices, and repurposing repowered turbines for a second life in the global south, as one contact of mine is doing. According to Michaux, that’s true.

Did you know that pumped hydro has no sites available and can’t scale, despite Michaux including the Australia National University study on closed loop off-river pumped hydro that proves exactly the opposite? Once again, Michaux — also not an expert in hydroelectric generation, dams in general, water turbines, or pumped hydro — claims that it won’t scale. China will be interested to hear that, as it has 365 GW of power capacity likely having something like 8 TWh of energy capacity in operation, under construction, or in plan to start before 2030.

Did you know that only hydrogen can work on trains that aren’t light rail inside cities, and that batteries can’t possibly work on trains? This despite pretty much the entire world except for North America just getting on with electrifying all rail, including with batteries for the gaps without wires. This is another insight from Michaux.

Did you know that batteries can’t possibly work on heavy-duty trucks? That will surprise pretty much every heavy-duty truck manufacturer, as they are selling far more battery electric trucks than hydrogen ones, and the battery electric trucks keep getting better and cheaper. Michaux would have you believe otherwise.

Did you know that maritime shipping couldn’t possibly electrify with batteries? Berkeley Lab’s 2022 paper showing 5,000 km economic breakeven distances with no subsidies for battery electric at cell prices of $50/kWh would beg to differ. Certainly China, again, will be surprised to hear that the 1,000 km routes that they are running on the Yangtze with battery-powered container ships are figments of their imagination. But never fear, Michaux is here with the truth, despite having absolutely zero previous publications or involvement in the maritime shipping or battery industries.

Did you know transmission interconnects don’t work due to the aforementioned 60% losses? China and others seeing 1.5% losses per 1,000 km with HVDC will be surprised. But trust Michaux, I guess. After all, he’s never published anything on transmission or the grid before, and has no experience in that industry either.

Did you know that, because of the — fictitious — 60% losses from wind turbines and solar panels to end uses, we need far more of them, but clearly we need a lot of nuclear too? That will surprise pretty much every serious modeling agency on the face of the Earth, ones which regularly find in actually credible studies that a bit of overbuilding of wind and solar, along with a reasonable mix of storage and transmission, is the cheapest form of energy system. But Michaux says different, so who are we to trust?

Did you know that every MW of wind or solar capacity requires weeks of storage? And that with that massive overbuild of wind and solar Michaux’ model requires, that multiplies vastly the amount of storage required?

Did you know that because he’s eliminated every other form of grid storage, including scaled ones that have been in operation for over 100 years and are being built by the TWh like pumped hydro, only batteries will work as storage, and there will have to be multiple times more of them than any other model ever created asserts? Mark Z. Jacobson and his team at Stanford, who have been iterating their constantly peer-reviewed, multiply iterated model of global energy with innumerable fine-grained publications on every aspect of it, will be surprised by that. But who are you going to trust, a team of economists and energy modelers at Stanford with hundreds of publications dating back 25 years, or a lone explosion dust expert in Finland?

Did you know that engineers can’t do metals substitutions in different applications, like using aluminum instead of copper in conductors, or building batteries without nickel or cobalt? I know, that’s a surprise to pretty much every engineer who has every worked on a battery or conductor, but the rock dust explosion expert rules it out.

Did you know that when you massively inflate the number of wind turbines and batteries, then require them to be built with lots of critical minerals like nickel, cobalt, and copper, you get incredibly big numbers for annual demand for those metals? That one shouldn’t be a surprise, because making up very big numbers then multiplying them together is pretty obvious. And that’s what Michaux has done.

But did you know that it means that we can’t possibly electrify everything because we can’t possibly mine or recycle remotely enough minerals? That too will be a surprise to pretty much everyone in the mining, energy, and recycling industries who are quite happily just getting on with it, but that’s what Michaux finds.

Prior to 2021 when he first published this magnum hopeless, Michaux had participated in exactly one study on the future of minerals with others. Before that he had a couple of publications about the world running out of minerals, one a book chapter. Even at that, it’s not like he is a standout academic. He’s around 50 years old, so was 47 or 48 when he published the first versions of this monstrosity in 2021. At the time his h-index was 8, which is well below the 40 which indicates a good scholar, never mind an exceptional one. It’s crept up to 12 since then, with most of the citations being to the first, non-peer-reviewed versions of these studies, and the second one seeing 64 citations, hopefully from papers which were either padding references or debunking it.

So, let’s talk about peer review. I mentioned Jacobson et al and their constant stream of peer-reviewed, published, and frequently criticized papers covering 25 years. Their model has been picked apart over and over, their assumptions have been field tested, and their methodology torn apart, often by wolves. While it’s been a rocky process at times, that’s the nature of major, influential studies that ignore well-funded stakeholder groups’ preferences to include the technologies they would like in the mix, especially nuclear and carbon capture. But their synthesis publications refer to dozens of specific publications by the team and other expert groups in different segments.

It still incites agitation. The treatment of hydroelectric facilities and transmission has drawn ongoing criticism, but frankly the evolution of those industries over time is much more aligned with Jacobson et al’s assumptions than with the critics’.

But all of those sub-papers have been peer-reviewed by appropriate reviewers for them. The model has been picked over by some of the best and brightest, as well as most motivated, experts in the world. Getting appropriate peer reviewers for Jacobson’s high-profile, well-respected work in a high-profile, globally respected research institution like Stanford is much more likely than getting remotely qualified peer reviewers for a low–impact factor house journal in Finland.

The sheer breadth of Michaux’ attempted energy modeling alone means that there are no academic peer reviewers who can cover more than a small fraction of it, and the complexity of it would require a cross-functional team working for months alone. The thought that this has been through anything remotely like credible peer review is laughable.

This is GTK pushing Michaux’ error-ridden but high-profile studies into their house journal for reasons of their own. It’s probably a strategic mistake, and undoubtedly was controversial. If any other GTK researchers contributed or wanted to add their names to it, then their names would have been added to it. If any of the researchers in the previous EU study had contributed or wanted anything to do with it, they would have added their names to it. No, this is one Australian mining explosion dust researcher, washed up in an earth sciences research institute in Finland, and no one else.

The GTK Bulletin’s editorial lead, Aku Heinonen, wrote a preface that reads in a distinctly apologetic way to me.

“The earlier work of the sole author of these two papers has been widely quoted, debated, and criticized in the media and amongst policy makers and academic audiences in the past few years. The premises, process, and conclusions of these studies have questioned the validity of some of the basic assumptions underlying the current energy and natural resource policy, but have still, largely mistakenly, been taken as a statement in favor of the status quo. On the contrary, these contributions are intended as the beginning of a discourse and attempt to bring alternative, often overlooked, views into the discussion about the basic assumptions underlying the material requirements of the energy transition.”

The bolding is mine. The reason for the “sole author” is that GTK and its other staff are trying to distance themselves from having too much tar smeared on them. It’s a clear assertion that this is Michaux’ work and no one else’s.

The reason it’s “been taken as a statement in favor of the status quo” is because Michaux’ egregiously bad papers are giving care and feeding to the people who don’t want to transition for any reason. If it hadn’t been useful to the fossil fuel industry, it wouldn’t have been amplified as if it were the second coming of Einstein, instead of the second coming of a crank mathematician-like actor Terrence Howard, who thinks he’s proven that one times one equals two, among other things. No one would have heard of Howard’s manifesto if he wasn’t a famous Hollywood actor, and no one would have heard of Michaux’ studies if they weren’t really useful to the fossil fuel industry.

To the point of being useful, when the subject of Michaux came up again recently because he was given yet another platform, this time by a media site which loves hydrogen for energy and as a result thinks anything which dismisses electrification is just peachy, I commented and left a copy of my last article on the subject from a year ago. One of Michaux’ defenders on the short thread that followed was a completely forthright climate change denier. Those are the Michaux’ fans.

It’s unclear why the GTK is lending this nonsense their credibility, because all it’s doing is reducing their own credibility. I suspect they have been heavily lobbied to eliminate one obvious mark against the studies, their lack of peer review, by giving them the pretense of peer review. For that matter, it’s unclear why they even gave the distinctly sub-par academic a job as a senior scientist and then associate professor starting in 2018. The organization is fairly narrow, but respected, especially for some comprehensive geological datasets it maintains. If they thought the subject was important, then they should have put competent people on it and collaborated with organizations which know what they are doing. Claiming after the fact that Michaux’ heart is in the right place and that the discussion is important is not grounds for lending their authority to his obsessive, solitary work.

I suspect that GTK is now caught between a rock and a hard place. They have ended up with a very controversial, clearly inferior academic on their payroll. He’s giving them a bad name just by being there. Whatever he’s supposed to be doing as a day job has undoubtedly suffered in the lead-up to the original 2021 publication, as he wasted all of his time creating two incredibly bad models from scratch, and suffered since then as he’s been on as many media interviews and panels as his fossil fuel fluffers can get him booked into. They can’t fire him for being a terrible academic and not doing his day job because they would open themselves up to nasty social media and right-wing media attacks, as well as political attacks in the Finish government.

I don’t have a lot of sympathy for them. They made their bed when they hired the crank, allowed his crank science studies to be published on their website, and promoted them, and now they have remade the bed. They are fully complicit in this.

Regardless, if anyone tells you that Michaux’ papers are now peer reviewed, tell them that there is no definition of peer review that would support that assertion. Instead, they have been published in a standalone edition of a low-impact house journal that’s normally peer reviewed by other in-house academics, none of whom have remotely the qualifications or time to do anything like a good job of it. Further, tell them that it is the opinion of a single rock dust expert, the least reliable form of evidence, not a remotely credible source.

Chip in a few dollars a month to help support independent cleantech coverage that helps to accelerate the cleantech revolution!

Have a tip for CleanTechnica? Want to advertise? Want to suggest a guest for our CleanTech Talk podcast? Contact us here.

Sign up for our daily newsletter for 15 new cleantech stories a day. Or sign up for our weekly one if daily is too frequent.

CleanTechnica uses affiliate links. See our policy here.

CleanTechnica’s Comment Policy