The Fed’s preferred measure of inflation is core PCE, which stands for Personal Consumption Expenditures index. This inflation gauge, published monthly by the Bureau of Economic Analysis (BEA), doesn’t include food and energy, because prices for these two categories tend to be volatile.

When the latest PCE numbers came out on Feb. 29, they showed January headline PCE was 2.4%, year on year, while core PCE was 2.8%.

Remember, the Fed’s targeted inflation rate is 2%. Inflation needs to be falling to somewhere close to 2%, for the Fed to consider lowering interest rates, having raised them 11 times since spring 2022.

Apparently the Federal Reserve, aka the US central bank, has been getting a bit more granular when deciding on its next monetary policy move.

According to Bloomberg, the now, even more important measure to the Fed than the core PCE is the so-called “Supercore” services inflation. It includes services without energy and housing.

“Inflation has been a hot topic for two years now. Many have become acquainted with the difference between headline and core inflation, with the latter stripping out the volatile food and energy components. However, over the past six months, an even narrower measure, dubbed ‘supercore’ inflation has become an area of particular focus for policymakers.

This is the component of inflation that includes mainly labor-intensive service sectors such as haircuts, cleaning services, childcare, and gym memberships (Chart 2). To be more exact, in the Fed’s preferred PCE measure of inflation, the Bureau of Economic Analysis breaks down non-housing service consumption into six major components: healthcare, transportation, recreation, food & accommodation, financial, and other services.

Using the PCE inflation data, non-housing services account for roughly 50% of core PCE inflation. However, this likely overstates its true weighting, as costs associated with medical services – less tied to the business cycle – account for roughly a third of that weighting. If that were excluded, the true “cyclical” component of inflation falls to a still significant one-third of core PCE inflation. For the purposes of this paper, and to be consistent with Fed’s recent messaging, medical is assumed to be included in our definition of ‘supercore’.

Price growth across non-housing services has remained exceptionally strong in recent months, with the three-month annualized change accelerating to 5.0% in February. Digging deeper into the data shows that gains have been led by transportation, recreation, and food & accommodation – all of which are running north of 8% (annualized) over the last three months – though price growth across financial and other services has also remained hot (Table 1).” Supercore’ Inflation Connecting the Dots to the Labor Market

January saw Supercore’s biggest month-on-month increase in a year, while the measure also ticked upward on an annual basis.

There is good and bad news in the Feb. 29 data.

On the positive side, it confirms that the extreme price shocks that came following the pandemic are over; gas and oil, eggs, televisions and car rentals are actively deflating.

However, the numbers for services, which are driven by wages, remain impossible to ignore.

Could January’s rise in Supercore inflation be an anomaly, within a more general downward trend? That is certainly possible, suggesting that inflation could come down further over the rest of the year, and result in what many, including us, believed will be three Fed rate cuts. However.

Bloomberg says this latest PCE appears to have confirmed the belief that rate cuts cannot start until June at the earliest. It’s harder for the Fed to cut than it appears, and impossible without clear evidence that inflation is already headed back toward its target.

Among those who think a rate increase, not a decrease, is coming, is Steven Blitz of TS Lombard, a London-based private banking company.

Blitz notes that in the January minutes of the Federal Open Market Committee, the Fed assured themselves that the upper limit of the federal funds rate’s current range (5.25-5.5%) is the peak for this cycle.

But, he writes, January personal income and price data offer evidence that their self-assurance might be misplaced. If the economy continues to expand apace (wage and salary disbursements, chiefly), there is little chance for service inflation to decelerate further and for goods prices to keep deflating (CPI goods ex food & energy turned up in January).

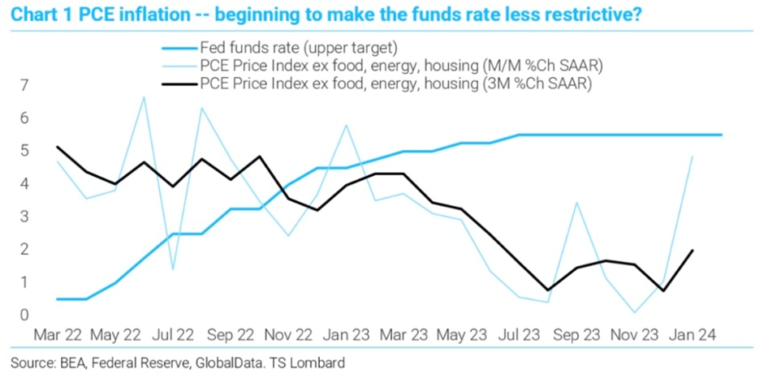

Furthermore, Blitz shows in the graph below that January’s rise in supercore PCE (excluding food, energy and housing) almost reached the 5.5% federal funds rate. And then the kicker:

While the January jump was so sharp that it may well be proved something of a flash in the pan, it would be hard for the Fed to allow its target rate to drop below the inflation rate. Another tick up in inflation could conceivably oblige a hike once more.

Let’s take a close look at the graph to better understand what’s going on here. The heavy blue line is the 5.5% federal funds rate (FFR). The black line is core PCE on a three-month basis. The light blue line is core PCE on a month to month (m/m) basis.

We notice the FFR closely tracks the m/m core PCE. When this inflation gauge spiked to almost 7% in June 2022, the Fed reacted by raising rates. Two more spikes occurred, first in August 2022, then in January 2023. After both instances the Fed kept raising rates. From that point, m/m core PCE started falling, registering only around 0.5% in August 2023. But the Fed held firm on its rate increases, likely hesitant to pause them until inflation reduction coalesced into a trend. The numbers certainly looked good. If we draw a straight line from the top of the first inflation spike in June 2022 to the bottom in August 2023, it shows a clear downward trend. This same trend is seen in the falling black line, the three-month core PCE.

But wait. See what happened last fall. In September, inflation suddenly spiked, then fell just as sharply, in November surpassing the August 2023 drop to the lowest level since the graph begins in March 2022.

Remember it was after the Fed’s December meeting that the group said it was penciling in three rate cuts in 2024. The numbers still looked good, clearly the Fed thought it had inflation beat, and only had to wait, and watch, while inflation continued to decline. Instead it has been climbing dramatically since November. The light blue line, m/m core PCE, at its latest data point in January, is very close to hitting the heavy blue line, the 5.5% federal funds rate.

As Blitz suggests, if m/m core PCE runs higher than the FFR, i.e., it surpasses 5.5%, that will be the signal for the Fed to raise rates, to cool inflation.

Conclusion

Unfortunately, we don’t get much closer knowing whether the Federal Reserve will raise or lower interest rates, and by how much, from its chairman, Jerome Powell.

Responding to those who think the only reason for a rate cut is political, i.e., to help get the Democrats re-elected in November Powell told members of Congress that upcoming decisions on when and how fast to cut interest rates will be based sole on economic data. (Reuters, March 6, 2024)

Powell also repeated the Fed’s mantra that it “would like to see more data that confirm and make us more confident that inflation is moving sustainably down to 2%” before reducing the federal funds rate.

But what if that is just a smokescreen for what’s really happening, i.e., that inflation as gauged by supercore PCE shown in the graph above is actually rising fast, not falling?

Reading between the lines, this could be what Powell meant when he cautioned lawmakers that continued progress on lowering inflation is “not assured”, and that Fed officials are concerned that the process of disinflation may stall.

Powell might be conditioning Congress, and the broader markets hanging on his every word, for a coming rate hike that few will have seen coming and that nobody wants.

Richard (Rick) Mills

aheadoftheherd.com

subscribe to my free newsletter

**********