Sign up for daily news updates from CleanTechnica on email. Or follow us on Google News!

In the short list of climate actions that will work (latest iteration), pricing carbon aggressively gets a spot of its own. This conservative, market-oriented fiscal policy that prices negative externalities of transactions follows in the well-precedented paths of pricing tobacco and alcohol. And it’s opposed by a remarkable number of self-described fiscal conservatives in multiple countries, remarkably many of the same people who opposed alcohol and tobacco taxes.

As I’ve noted many times, pricing carbon is an essential lever in the control room of carbon minimization, but it’s typically inadequate by itself. That’s because it’s hard to get jurisdictions to actually price carbon appropriately. One of my more recent assessments was of the social cost of carbon, now a unified methodology between the USA and Canada, where around $190 is the strike point for 2023 (all amounts in USD unless otherwise indicated). That means that every ton of new CO2 or equivalent that’s introduced to the atmosphere by our human actions costs the world almost $200 in the future.

And that number increases every year, with 2030 seeing $218, 2040 seeing $252, and 2050 seeing $292.

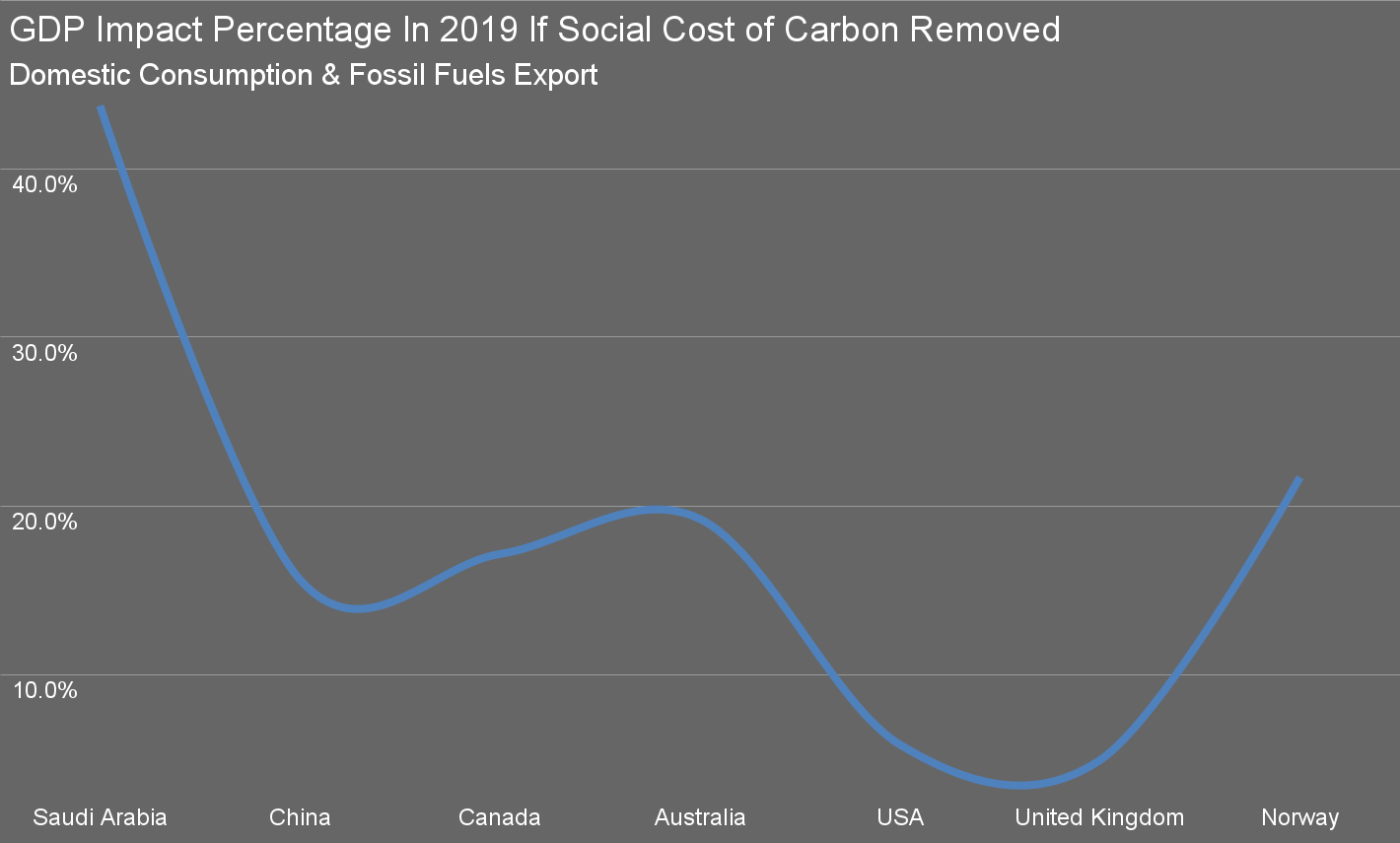

GDP Impact Percentage In 2019 If Social Cost of Carbon Removed, Domestic & Exported GHG Emissions

Just the current value, if removed from GDP, would have very significant impacts on many countries’ economies. Canada’s oil sands alone cost the world $85 billion more every year than their total revenues.

But carbon prices aren’t aligned with these very serious fiscal impacts. Canada’s carbon price, while excellent and improving, is only about $48, a quarter of the social cost. And when it peaks in 2030, it’s still going to be well below the social cost in that year. Australia’s equivalent of Washington, DC, is the only part of Australia that publishes a social cost of carbon, and it’s only $6.50. China’s cap and trade is at $10.50 right now. California’s cap and trade, which includes eleven US states (and two Canadian provinces) is at $30.

We aren’t pricing carbon high enough. Europe is doing the best at it. Its carbon price is currently $92, and peaked at $107 recently. But even at those prices, Europe’s actual cost per ton right now is about half of what at least Canada and the USA think it should be. But what guidance is Europe giving organizations about the future cost of carbon?

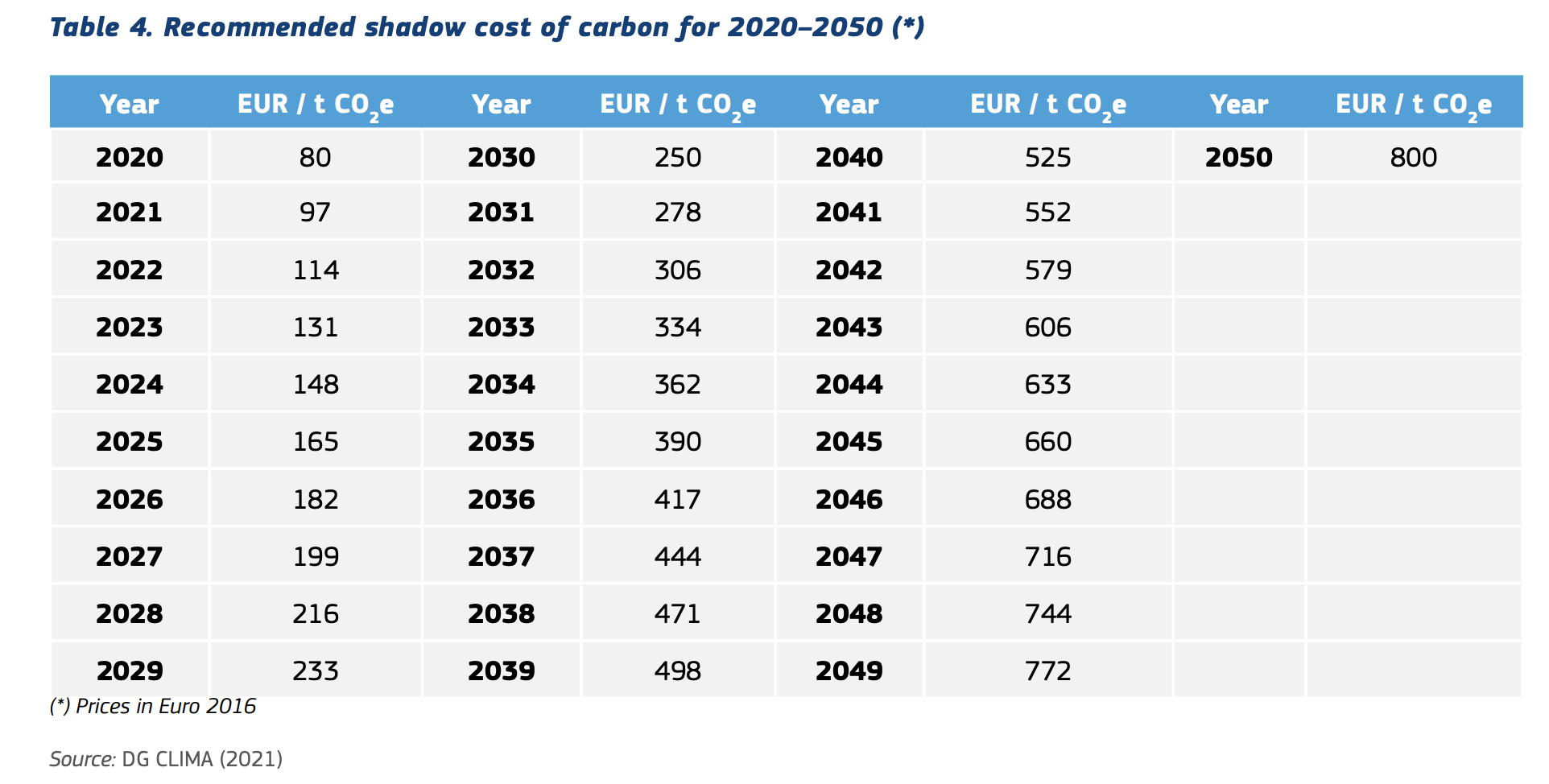

Guidance on budgeting for carbon costs through 2050 from EU

When I wrote about this climate action lever recently, a European contact pointed at this table in guidance that the European Commission provides to member states regarding how they should be pricing carbon in cost benefit analyses. These CBAs aren’t mandatory, but are recommended for a host of project types and scales, from waste and wastewater projects to research and development to urban development. The intent of these numbers is that they aligned with 1.5° Celsius of warming.

The euros in the table are interesting, even startling, but let’s do an apples to apples comparison.

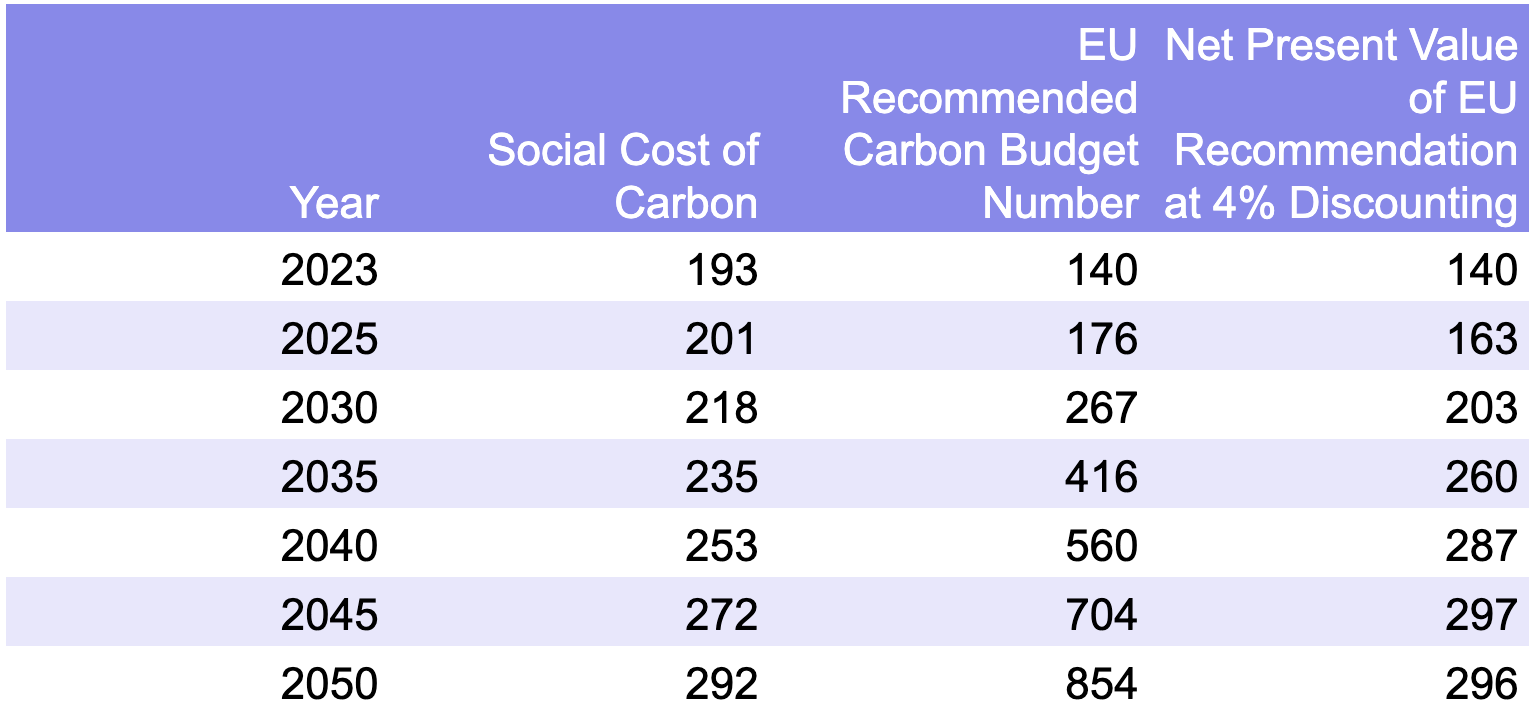

Comparison of US-Canadian Social Cost of Carbon to EU Recommended Budgetary Cost of Carbon through 2050

The EU numbers get very big, very fast, but that’s an artifact of overcoming typical challenges of the budgeting process, hence my addition of the third column, net present value.

NPV is a business-casing approach that makes perfect sense, except when it doesn’t. All it really says is that costs in the future will be paid in future currencies and hence subject to inflation. What this often means is that people make estimates of the cost of cleaning up messes in today’s dollars, then put that number in the future column, and the magic of net present values turns it into something approaching zero.

That’s an approach that leads to intergenerational inequity, where costs of cleanup that are very real don’t impact current business cases, because NPV makes them approach zero, but the cleanup still is required by future generations. It’s one of the accusations reasonably applied to nuclear energy, where decommissioning costs of reactors built today are 40 or 60 years in the future. As I’ve noted before, decommissioning costs from old reactors are hitting budgets these days and making policy makers’ eyes widen, with billion dollar price tags and up to a century for full remediation and release of sites.

Of course, this has implications for the fossil fuel and mineral extraction industries as well. Oil, gas, and coal companies are notorious for finding ways to abandon once productive properties for taxpayers to clean up, with Alberta’s industry alone having about $200 billion in liabilities per one assessment.

The EU budgetary guidance is intended to overcome that problem by building in future prices that have been grossed up already to account for NPV failures. That climate change impacts will occur decades in the future does not mean that the costs aren’t real, or that business cases shouldn’t include them.

EU budgetary guidance, at least right now and at least from this document, is to use a 4% per year discounting rate. Every year in the future, a lump sum is worth 4% less, compounded. It’s the opposite of the magic of compounding interest on your savings.

You’ll note that the social cost of carbon in the US- and Canada-aligned methodology tracks reasonably closely with EU budgetary guidance.

But what does this mean?

Well, for projects expected to be built in 2030 in the EU, they have to account for the carbon dioxide and equivalent emissions at around $203 in today’s dollars per ton and put that cost on the negative side of the ledger. The EU is signaling very clearly that it expects to have its emissions trading scheme approaching that if possible.

Let’s take a hypothetical 1 GW capacity wind farm and a hypothetical 1 GW capacity natural gas plant and play them out through 2050. Let’s run them at the same capacity factor of 40%, because we sure aren’t going to be running gas plants 24/7/365 if we actually want to solve climate change, so we’re going to run them only enough to keep the lights on and the homes warm. Let’s assume the wind farms get $50 per MWh on average, a reasonable wholesale electricity price that’s below the average wind and solar farms get by leaning into maximizing profits. Probably low for the gas plant which will be there for dead zones where the price of wholesale electricity shoots up, so let’s give it $100 per MWh.

They’ll each produce 3,500 GWh over each year. The wind farm’s operations are carbon-free, but it has embodied carbon in the steel, concrete, and composites, so it’s going to be producing about 8 tons of CO2e per GWh of electricity. Meanwhile, between upstream methane emissions (that’s at the low end of emissions, by the way) and the CO2 from burning the natural gas, the gas plant is going to be producing 600 tons of CO2e per GWh. The EU is only putting methane into the carbon price in 2026, but for the purposes of this assessment, I’ll price it immediately.

Let’s say that they are built in 2024 and both become active at the beginning of 2025. Also, that they will pay for the CO2e emissions against MWh of production as opposed to in the year of construction (a bit flakey, but it’s for illustrative purposes).

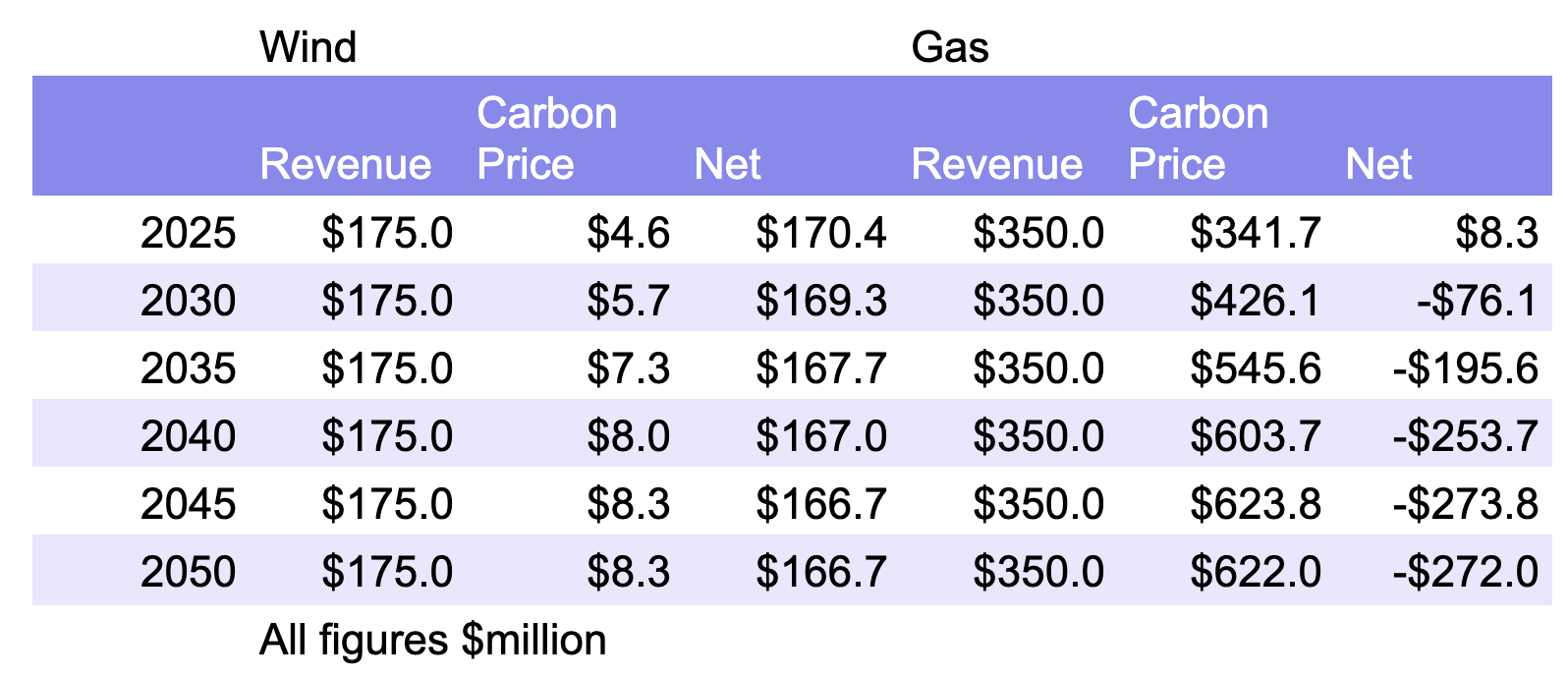

Projection of Wind Farm vs Natural Gas with EU carbon price budget numbers

For the purpose of this projection I’ve assumed 4% increases in revenue every year so they stay stable, with only the carbon price increasing in cost over time. This also excludes everything except revenue and carbon price, while there are more construction and operational costs to consider.

Sharp eyes will notice that the gas plant makes a bit of money in 2025, but then becomes increasingly underwater with the passage of time. Meanwhile, because wind energy emits no CO2e during operations, but is only paying back the embodied carbon debt, it’s vastly more profitable immediately and its profits only slightly diminish.

In fact, the wind farm could pay the entire carbon debt of $42 million in its first year and still be over 15 times more profitable than the gas plant. One wonders why anyone would consider building a natural gas plant these days. The answer, of course, is that they want to run it under 10% of the year, and only when the wholesale cost of electricity is at its highest. Even at a tenth of the capacity factor, 4% generation per year, getting twice the price per GWh on average, they are barely in the money in 2050 just on the revenue vs carbon ledger. The other reason is that they are betting that they can make enough money before carbon pricing kicks in to pay for the initial capital costs and find a way to dump the stranded asset and clean up off of their books.

Another way to look at this is that the EU is signaling strongly that the emissions trading scheme will be managed to these levels. As a reminder, the ETS is the price basis for the carbon border adjustment mechanism. Everyone in the world exporting to Europe will be paying this price per ton for the embodied carbon in whatever they ship to the continent. This is the projected carbon price for the world.

Have a tip for CleanTechnica? Want to advertise? Want to suggest a guest for our CleanTech Talk podcast? Contact us here.

EV Obsession Daily!

I don’t like paywalls. You don’t like paywalls. Who likes paywalls? Here at CleanTechnica, we implemented a limited paywall for a while, but it always felt wrong — and it was always tough to decide what we should put behind there. In theory, your most exclusive and best content goes behind a paywall. But then fewer people read it!! So, we’ve decided to completely nix paywalls here at CleanTechnica. But…

Thank you!

Tesla Sales in 2023, 2024, and 2030

CleanTechnica uses affiliate links. See our policy here.