Europe is running out of time to implement a large-scale support scheme, comparable with the U.S. Inflation Reduction Act (IRA), in order to revive its solar photovoltaic (PV) manufacturing industry base, industry leaders said at Intersolar Europe in Munich, Germany.

The European Union’s reaction to the challenges presented by the IRA, as well as China’s dominance over the supply chain, may not be sufficient. Brussels’ response could fall short of enabling the region to achieve its ambition of building 30 gigawatts (GW)/year of solar manufacturing capacity by the end of the decade, according to speakers from the European Solar PV Industry Alliance (ESIA).

However, the biggest hurdle confronting European industry is high running costs, particularly energy prices that are three to five times higher in Europe than in China or the U.S.

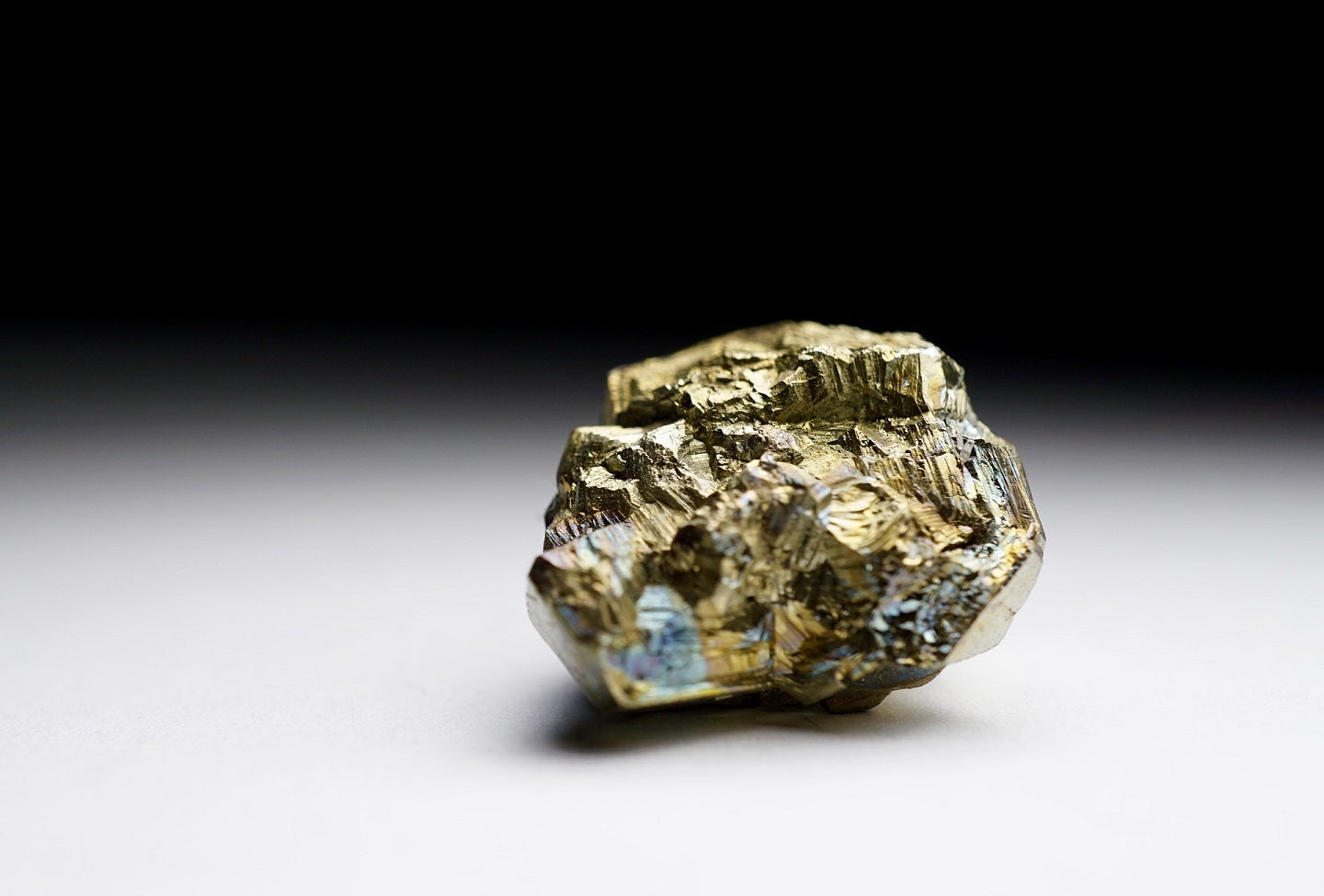

“The gap for operational expenditure, based on energy, is increasing significantly with the electricity price, and the most energy intensive steps, which are polysilicon, wafer/ingot and glass, suffer the most,” said Dr. Christian Westermeier, chair of the ESIA finance working group and head of Wacker Chemie AG, Europe’s sole polysilicon producer.

“If we don’t find a solution for this opex part, everything is void.”

Closing the Funding Gap

Westermeier argued that between €4.7 billion and €6.4 billion ($5.1 billion-$7 billion) of support annually will be needed for up to 10 years for Europe to build a competitive and resilient solar industry. This compares to the €4.4 billion/year that the ESIA estimates the IRA is providing to kickstart solar manufacturing in the U.S.

Access to capital is another challenge, with financing for those companies with projects still not easily available, said Westermeier. Compared to China, Europe’s capital expenditure funding gaps range from €5.3 billion for polysilicon, €1-1.5 billion for ingot and wafers, and cells and modules around €1.5 billion, according to ESIA data.

Overall, the ESIA reported that the U.S., with IRA support, has a solar power cost around €0.16/watts direct current (Wdc), which is even lower than that of China. In contrast, Europe’s production cost is double that level, even at the so-called low €50/megawatt hour (MWh) electricity price scenario, which is more aligned with the U.S. production cost before the IRA came into effect.

“The U.S. is doing the right steps to really encourage companies to move to the U.S. and build up capacity there. And the big advantage of the IRA compared to what we are currently discussing in Europe is that the IRA provides clear numbers, clear process and easy to access financing,” Westermeier said.

Christoph Podewils from leading Swiss panel maker Meyer Burger and co-chair of ESIA’s supply chain working group, said the funding intensity of the IRA is more than 60% of the factory gate prices. “A similar support mechanism would need to be implemented in Europe through general and direct incentives or grants for manufacturers,” Podewils said.

Meyer Burger is planning to expand its U.S. business, announcing in April plans to increase module capacity from 1.6 GW to 2 GW at its Goodyear, Arizona, facility in the U.S., not least due to the “currently more favorable industrial policy support for the solar industry, compared to Europe,” the company said in a recent announcement.

Defining Best in Class

Europe’s solar PV industry has been vocal about incorporating environmental, social and governance (ESG) criteria into the supply chain to help level the playing field for European manufacturing and draw investors and project developers. But the construct around ESG remains vague without clear definitions set in industry or legislation.

Jörg Ebel, co-chair of the ESIA’s demand side working group and vice president at IBC Solar AG, outlined proposals to ESG criteria to define ‘Best in Class’ solar to improve transparency in the supply chain and for use in the public procurement process.

The ESIA proposed that points would be accrued to reward high performance as set out in Best in Class practices. Highly weighted criteria included a recommended carbon footprint threshold measured by the Electronic Product Environmental Assessment Tool (EPEAT), as well as metrics for recycled content, local job creation, and supply diversity amongst others. The Best in Class practices should account for 40% of the award criteria for tenders, up from 15-30% currently for sustainability and resilience contributions, according to proposals from the working group.

Moreover, the ESIA called for the early adoption of the EU Forced Labour Ban Regulation in a similar vein to the U.S. Uyghur Forced Labor Prevention Act (UFLPA) that came into effect in December 2021. This prohibits the import of products from China‘s Xinjiang province where, according to the International Energy Agency, 40% of global polysilicon originates, and so restricts the flow of Chinese manufactured modules into the U.S.

Back to Brussels

The Temporary Crisis and Transition Framework (TCTF) and Net Zero Industry Act (NZIA) adopted this year, while a step in the right direction, were too unwieldy and complex for companies to understand and embrace, according to Westermeier.

Specifically, under the TCTF, the ESIA urged for opex aid around electricity costs to be considered alongside capex to the level of the €4.7 billion/year level needed to develop Europe’s solar industry, and to scrap the 30% cap on capex support. Furthermore, a ‘matching clause’ which the EU is offering to lure solar developers back to Europe away from a comparable investment in the U.S. is a very complicated process, Westermeier said. Geographical restrictions that put a lot of different and additional hurdles for investment cases need to be removed, he added.

For the NZIA, the alliance maintained that support needed to be extended to the entire solar value chain including materials and components, “not just a few topics — this is not helpful,” said Westermeier.

Meanwhile, the solar industry industry in Europe has only a matter of a weeks to finalize concrete proposals on how to improve the TCTF and NZIA for presentation to the European Commission in July.

“There is not much time left for us if we really would have the ambition to come up with 30 GW by 2030,” said Westermeier. “We really need to move fast.”

Editing by:

Rob Sheridan, rsheridan@opisnet.com