Sign up for daily news updates from CleanTechnica on email. Or follow us on Google News!

Freight logistics are going to be transforming over the coming years, and electrification is the primary wedge. It’s not only climate-friendly, but ports that take this path sooner rather than later will end up more competitive as global shipping declines. Electrification is a path to being a winning port in the shakeout that’s coming.

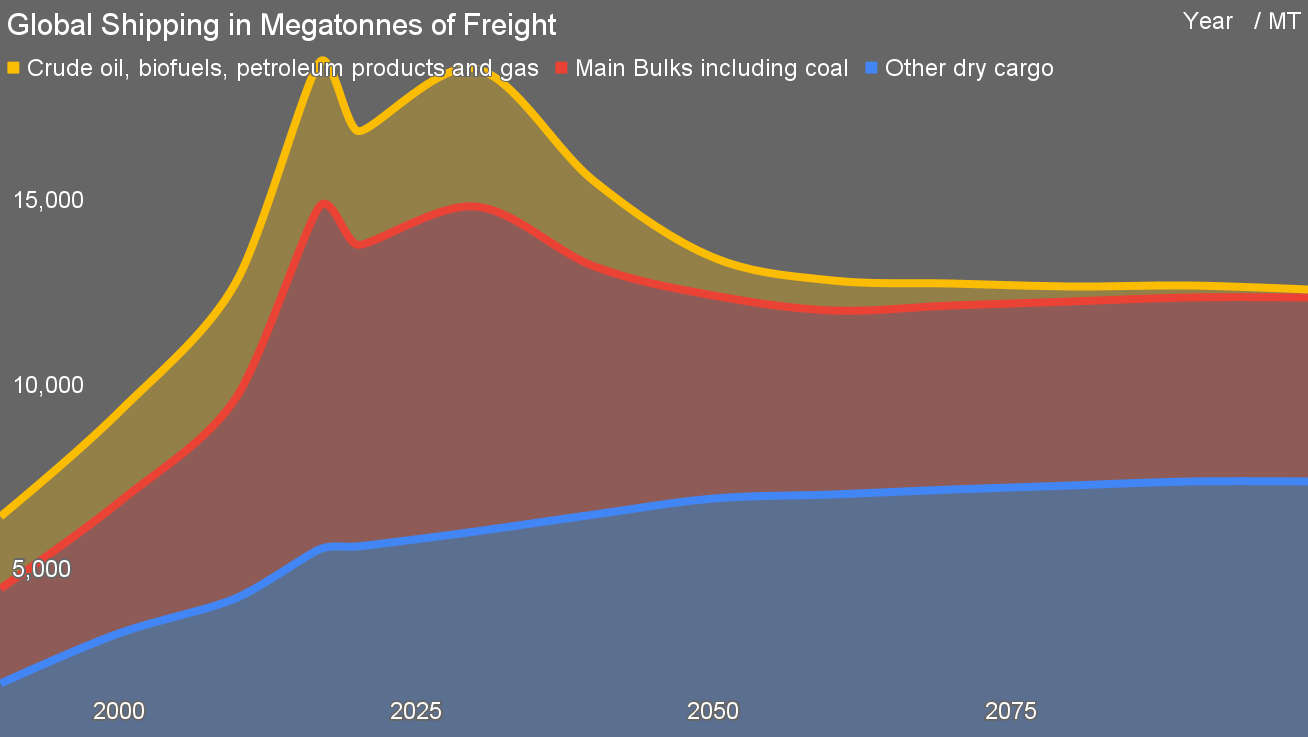

Nobody in the shipping industry likes this chart, but it’s realistic, unlike the International Maritime Organization’s official position that the industry is going to be growing a lot in the coming years. Let’s unpack it a bit.

First, it’s worth noting that we’re not going back to the levels of shipping seen in 1990. However, we’re also probably not going back to peak shipping in 2020. Why is that? If you look at the legend of the chart, you’ll see petroleum, gas, and coal. This is the decade of peak fossil fuels globally, and unconventional extraction of gas and oil is an exportable technology. Both China and India are piloting unconventional extraction techniques to fulfill their to-be-dwindling demand for fossil fuels.

And they will be dwindling. Last year, organizations such as Asia-based Lantau Group were pointing to peak coal in China this year. This year, monthly year-over-year coal generation numbers are down by 3.7%. Sinopec asserted that peak gasoline in China was in 2023, which likely means peak diesel was that year as well. Natural gas generation is off by TWh from 2023 to 2024 as well. Coal capacity factors are plummeting, 7% down from last year. This is to be expected when China is building more wind, solar, hydro, transmission, and storage than the rest of the world combined and still accelerating its deployments.

Europe has also seen a significant decline in fossil fuel generation, with the hard work since 1990 positioning it to reduce the role of Russian gas in its economy quite rapidly. US coal generation has plummeted, and exports, while up, have been nowhere near the degree of reduction. The only growth segment for fossil fuels is petrochemicals, which aren’t going to be growing nearly as fast as energy demand from fossil fuels falls.

And 40% of maritime bulk shipping is of coal, oil, and gas bulks. That’s mostly going away.

Similarly, bulk shipping of iron ore — 15% of bulks — and scrap steel is going to decline as well. The reasons are similar. China’s enormous appetite for steel is entering a structural decline as it has built most of the infrastructure and cities that it requires. Modern iron-making techniques such as hydrogen direct reduction of iron and molten oxide electrolysis are coming online to replace blast furnaces, and those processes can run on sunshine near mines without coal or gas. The tens of millions of tons of scrap steel that are shipped each year — 18 million from the USA, 10 million from the UK, 18.5 million from the EU, etc. — are intentionally being targeted for use in domestic electric arc furnaces that once again can run on sunshine (and increasingly do).

That’s 55% of bulks that are in significant structural decline starting this decade. There will be some additional bulks from green ammonia manufactured in places with lots of sunshine, water, and empty space shipped to farms around the world. There will be some additional biofuels from very green places with relatively few people to the airports and ports of the world for longer haul aviation and shipping. But these increases won’t begin to replace the bulks that are going away.

At the same time, container shipping will continue to take more and more of what were traditionally bulk markets, growing their domination of the space. Agricultural dry bulks have seen a significant shift to containers, for example, something likely to continue.

There are about 900 big ports in the world, split between ones that have heavy concentrations of container shipping, ones that are more focused on bulks, and specialty ports for things like liquid fossil gas (LNG) and liquid ammonia. The LNG ports aren’t going to become hydrogen ports, although some might become ammonia ports in the future, but that won’t make much of a dent. Total LNG shipping in 2023 was 408 million tons, while ammonia’s total global market was about 195 million tons. That number isn’t going to go up. Quite the opposite, in fact, as nitrogen-fixing agrigenetic solutions, precision agriculture with drones, and low-tillage agriculture take hold, it will be made from sunshine closer to the farms it will be used on more in the future, and shipping will shift from fossil methane giants like Russia to places with lots of sunshine, water and space.

What’s coming is a massive competition by ports for containers. Some bulk ports will simply dwindle to a rump of their former selves, or if they currently do agricultural bulks such as Stockton, California, will persist. But many bulk ports will be trying to reinvent themselves as container ports. Ports which are balanced today will be expanding the container side of their business at the expense of space currently devoted to bulks. Ports which focus on containers today will be trying to keep their market share.

This is where electrification comes in. Port operations burn a lot of diesel right now to shift containers around. Most of the big ports have already electrified the big stationary cranes, but even there, many are using diesel generators to provide the electricity. Reach-stackers, straddle carriers, and container tractors are running 24/7/365 in ports all over the world, moving at relatively low speed but hauling big loads and lifting them significant distances as well.

While recent studies have found no consistent signal yet for renewables’ impact on electricity cost, with fossil fuel price spikes, taxes, and surcharges making up much more of the variances, in the long run the consensus is that electricity will be cheaper. Further, in most jurisdictions the taxes on fuels will be going up, while surcharges on electricity will be going down. Until recently, Germany’s electricity retail prices were among the highest in Europe despite its wholesale prices being among the lowest, but now it’s rolling out industrial rates as low at €0.06 per kWh, eliminating policies that favored efficiency over electrification in favor of sensible policies that favor electrification of everything.

India has a tax on diesel, although not high enough per the IMF, still constituting a subsidy. Canada’s carbon price applies to diesel. The EU’s emissions trading system is rapidly eliminating allowances for fuels. Replacing fossil diesel with synthetic or biodiesel isn’t going to help. Biodiesels are 2-3 times as expensive. Synthetic fuels will be 4-6 times as expensive per the IEA’s 2023 e-fuels report.

Electricity will get cheaper. Batteries are already plummeting in price. Burnable fuels will be more expensive. Any port that persists in burning fuels will end up having to charge more for their services. And that will be in a very competitive space where big ports are going to be at risk of becoming small ones and smaller ones have the opportunity to take a much bigger chunk of market share.

This isn’t the only reason. As I noted recently in From Risk to Reward: Electrifying Supply Chains for Competitive Products, in a piece the editor in chief of the Journal of Sustainable Marketing requested from me, carbon pricing is increasingly going to include Scope 3 emissions. Scope 1 emissions are direct greenhouse gas emissions from sources owned or controlled by the company, such as fuel combustion in company vehicles. Scope 2 emissions are indirect emissions from the generation of purchased electricity consumed by the company. Scope 3 emissions encompass all other indirect emissions that occur in a company’s value chain, including both upstream and downstream activities like product transportation and waste disposal.

At present, Scope 3 is excluded from carbon prices on products. But all countries with carbon pricing are looking at the space because it’s often quite a big portion of overall carbon debt of products. The European Union certainly is, and that’s a big concern for ports for the simple reason that Europe is the biggest trading economy in the world. It exports and imports more than any other equivalent geography as a percentage of GDP, and as a portion of the world’s economy. Its carbon border adjustment mechanism is kicking into fiscal impact land in 2026 with a rising percentage of the ETS value applied through 2032, when it will be at parity.

As I noted late last year, the budgetary guidance has the carbon price at around US$215 per ton in 2030 and around $305 in 2040. For ports, that means a decarbonized port is a port that gives its customers a competitive advantage, and ports will be competing among themselves for the declining overall pie and the increasing container pie.

Major distributors aren’t waiting. I’ve been having a series of conversations related to attempts to electrify US rail in the past couple of months, for example with Berkeley Labs’ rail electrification lead and with entrepreneurs who are trying to find a solution for the space. As I noted recently, electrified trucking is now lower carbon than rail in eight mostly affluent US states, including California, and 70% of Canada. Distributors like Amazon are taking note and are telling Class 1 rail CEOs to figure out electrification or see containers shift to electric trucks. This when 33% of US rail tonnage is disappearing as coal dwindles. When Amazon decides to shift its global container movement from one port to a different port with lower carbon emissions, the losing port really will be losing and the winning port will be seeing a economic boom. Just as Walmart historically caused packaging to shrink to fit the content, major customers of the logistics industry are going to be leaning into decarbonized logistics.

Then there are labor aspects. As with electric vans and electric trucks, electric port vehicles are in high demand among port workers. Sahar Rashidbeigi, head of decarbonization for APM Terminals, the division of shipping giant Maersk that has the container concession for around 8% of global ports, shared with me recently that as she leads the charge on electrification, they are having to put quotas for port workers on how often they get the electric port vehicles to avoid conflict.

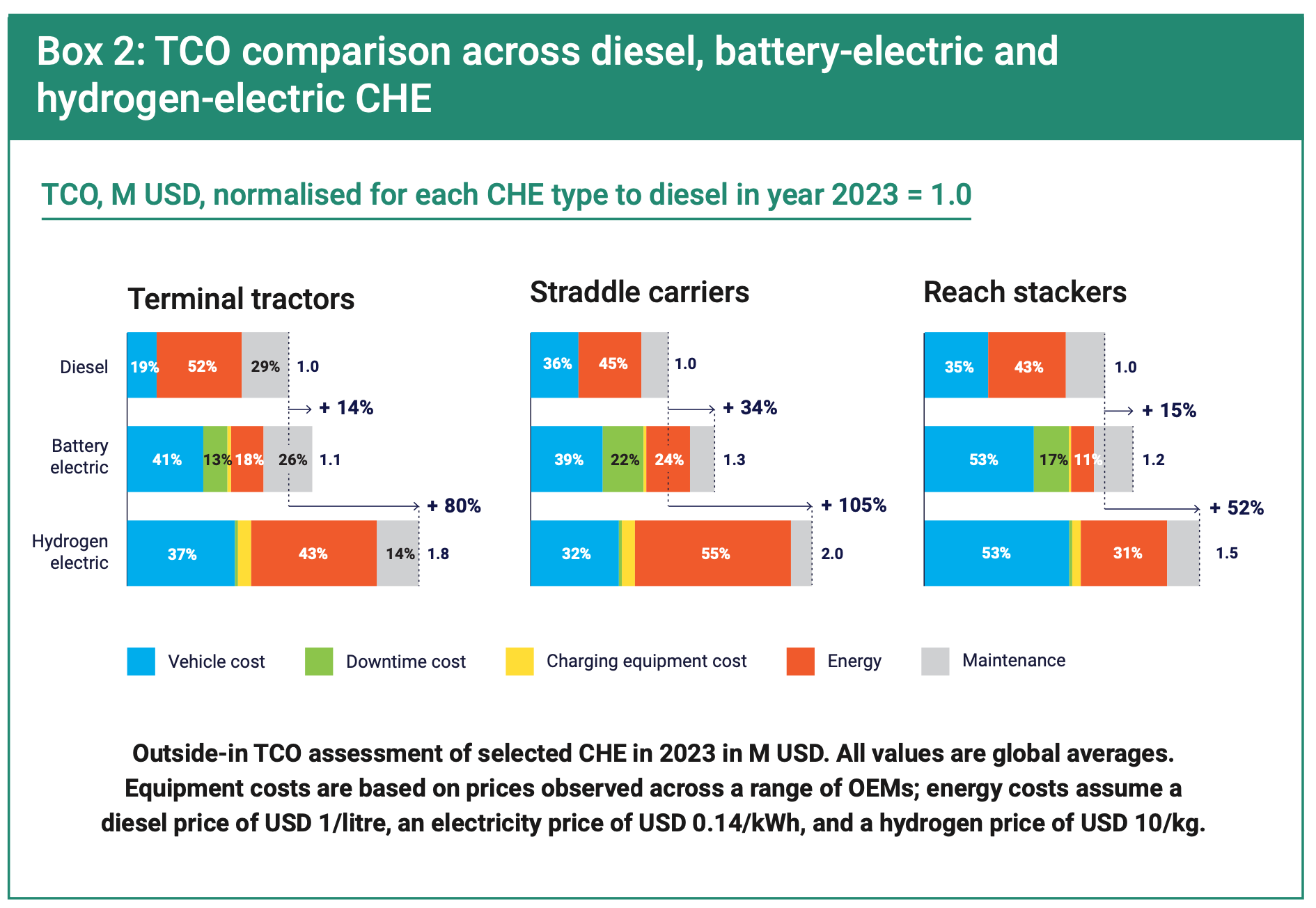

As a reminder, Rashidbeigi and her team did a total cost of ownership study last year that found that even then, before battery costs plummeted as they did this year, electric port vehicles were going to be a lot cheaper to own and operate than hydrogen vehicles.

It’s not just the preference for quiet vehicles that don’t stink or vibrate and have all the power anyone could want, it’s also a health question. That noise, vibration, and diesel pollution comes with health impacts. These are vehicles that aren’t mandated for emissions control to nearly the extent that road vehicles are. Workers are losing work days to illnesses caused by this, and have significant health impacts that persist through retirement and often cause premature death, including cardiopulmonary diseases and cancer.

A sick workforce isn’t a productive workforce. A sick workforce isn’t one that’s easy to gain workers for. A port with a healthy workforce that’s driving quiet, noise-free electric vehicles is a port with higher worker satisfaction, resource retention, and fewer concerns about medical insurance and health-related lawsuits. This too contributes to port competitiveness.

A competitive port is one that will increase volumes in coming years, requiring more workers. Forward thinking unions will welcome electrification with open arms, not only for the health and happiness of their members, but to help the port increase its throughput and hence require more union member hours every year.

Electrifying ports floats all boats, well, except for the boats of people selling diesel for port operations. They’ll be relegated to car-top aluminum boats with outboard motors — electric, of course.

Have a tip for CleanTechnica? Want to advertise? Want to suggest a guest for our CleanTech Talk podcast? Contact us here.

Latest CleanTechnica.TV Videos

CleanTechnica uses affiliate links. See our policy here.

CleanTechnica’s Comment Policy