Sign up for daily news updates from CleanTechnica on email. Or follow us on Google News!

Carbon dioxide emissions in China are on track for their first annual decline since 2016, a signal the world’s top polluter may have already hit a peak in its output of greenhouse gases, Bloomberg reports. Coal use for power generation plunged last month, while oil consumption contracted in the second quarter as renewable energy output and adoption of electric vehicles increased. Both of those factors increased expectations that the nation’s emissions will contract this year.

A shift in China’s economy away from emissions-intensive sectors, and a tentative retreat of fossil fuels, raises the prospect that any decline could be sustained and mean carbon pollution topped out last year, well ahead of President Xi Jinping’s 2030 target. “We are at a moment where clean energy growth is larger than demand growth,” said Bernice Lee, research director at Chatham House, an international affairs consultancy. “If it is true that real estate is no longer seen as the engine for growth, then it is likely you could see emissions projections going down.”

China accounted for more than 30% of the world’s emissions in 2022 and has driven the increase in the global total for many years. Coal-fired electricity generation slumped for a second straight month in June and declined 7.4%, the biggest drop since May of 2022 when Shanghai was in a Covid lockdown, according to data released Monday by China’s National Bureau of Statistics. Oil demand in China slipped into a marginal contraction in the second quarter as weaker growth has dented consumption of transport and industrial fuels, the International Energy Agency said earlier this month.

Clean Power Surging In China

Generation from renewables is meeting nearly all new demand, according to the National Bureau of Statistics in China. Bloomberg cautions that the data only includes large facilities, which means any contribution from rooftop solar is likely undercounted. Record installations of solar panels and wind turbines mean renewable energy generation is surging, which helps reduce reliance on more polluting sources even as power demand rises. If China’s rapid deployment of solar and wind continues, the country’s carbon emissions are “likely to continue falling, making 2023 the peak year,” Lauri Myllyvirta, senior fellow at the Asia Society Policy Institute, said in a report last week.

China’s economy is also undertaking a structural shift amid a long term deflation of the real estate sector. That has resulted in lower output of materials like cement and steel, the two largest carbon-emitting activities outside of the electrical energy sector, yet the trajectory for China’s emissions will depend on the government’s response to a slowing pace of growth. If the country elects to continue the pursuit of Xi Jinping’s long term objective to prioritize high tech industries, carbon emissions may rise rather than fall in the future. “They could just say there’s another stimulus again,” Bernice Lee told Bloomberg.

China is investing in new power lines and energy storage systems, and considering additional market-based reforms to ensure clean electricity generation is used efficiently. Even if the nation’s carbon emissions have now peaked, the volume remains so large that it will be the pace of the decline that is now critical for the world to be able to achieve global net zero targets.

Carbon Brief Report On China Emissions

A new analysis for Carbon Brief, based on official figures and commercial data, reinforces the view that China’s emissions could have peaked in 2023. The key findings from the analysis include:

- Wind and solar growth pushed fossil fuels’ share of electricity generation in China down to 63.6% in March 2024, from 67.4% a year earlier, despite strong growth in demand.

- The ongoing contraction of real-estate construction activity in China saw steel production fall by 8% and cement output by 22% in March 2024.

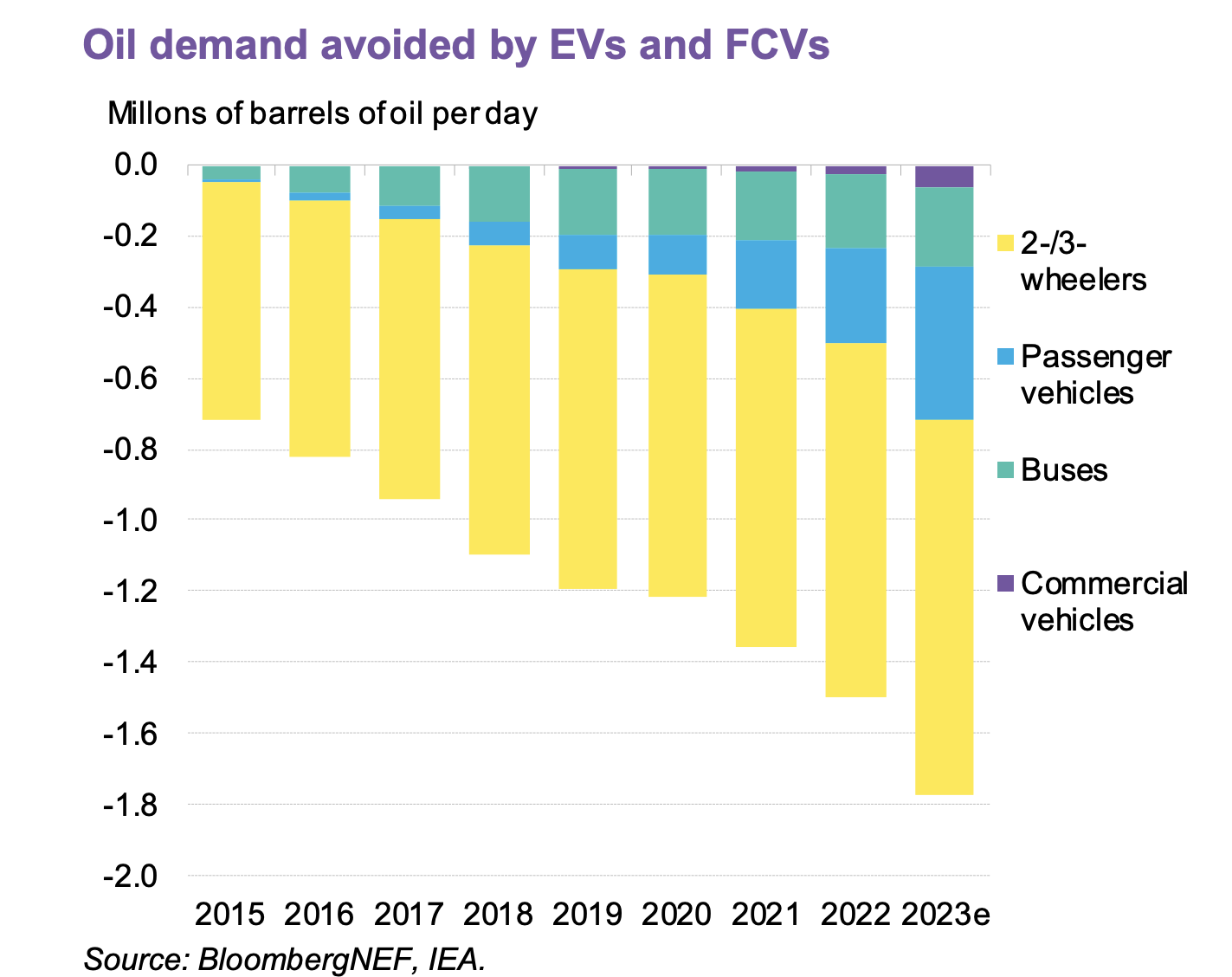

- Electric vehicles now make up about 10% of all the vehicles on China’s roads, paring around 3.5 percentage points off the growth in petrol demand.

It is unlikely that manufacturing growth in China can continue as global markets for various goods and commodities become saturated, Carbon Brief says. The government is now emphasizing “new productive forces” — an attempt to shift economic growth away from traditional heavy industry to high end manufacturing and R&D which are less energy intensive than China’s traditional industrial sectors.

Renewables are responsible for holding emissions from power generation in check despite a significant increase in the demand for electricity, which rose by 7.4% since the beginning of 2024, and a reduction in the amount of hydro power available due to lower water levels due to a prolonged drought in many parts of China. Renewables in March were responsible for 22% of all electricity in China in March and represent 90% of year over year growth since March of 2023.

What the statistics don’t show is the amount of power created by distributed solar sources. The reported electricity consumption in China is often greater than the reported amount of electricity generated — a logical impossibility. Bloomberg has called this a “missing data problem.” The National Bureau of Statistics only reports monthly power generation from very large-scale solar and wind installations. Since 45% of the record-setting solar additions were from distributed renewables, the exclusion of small solar installations is likely responsible for the “missing data” effect. The widening gap between electricity consumption and large scale power generation makes it clear, however, that distributed solar is increasingly contributing to meeting electricity demand, Carbon Brief says.

The fall in China’s emissions in March could mark a turnaround after blistering growth since 2020. Whether the clean energy growth will continue is the key question for the future path of China’s emissions. Internal policy estimates vary widely, making it difficult to assess where China is headed in terms of carbon emissions from power generation. It should be noted that the country also has 200 GW of new coal generation on the drawing boards.

Other Climate Emissions Rise In China

While carbon dioxide represents three-quarters of the crud humans spew into the atmosphere, a slew of other pollutants contribute to global overheating as well. The production of aluminum and semiconductors depends on two gases that are up to 10,000 times more powerful than carbon dioxide and remain aloft in the atmosphere for thousands of years. Perfluorocarbons — tetrafluoromethane and hexafluoroethane — are used in the manufacturing processes for flat panel TVs and semiconductors and are by-products of aluminum smelting.

A research team led by Minde An at Massachusetts Institute of Technology examined the emissions of those two gases in nine cities across China from 2011 to 2021. They found that both gases exhibited an increase of 78% in emissions in China and, by 2020, represented about 65% of the global total for both. The emissions were found to mainly originate from the less populated industrial zones in the western regions of China where the aluminum industry has a major presence. China is the world’s largest producer and exporter of aluminum, with a record high output of 41.5 million tons last produced in 2023, according to The Guardian.

Here’s the thing, While those emissions are worrying, aluminum is essential to the transition from fossil fuels to cleaner renewable energy sources because of its use in low carbon technologies such as solar panels, electric vehicles, and wind turbines. Organizations such as the World Economic Forum argue that the aluminum industry must act now to find a balance between ensuring efficient production alongside mitigating the industry’s negative impacts on the climate.

The Takeaway

The good news here is that China has lowered its carbon emissions so far in 2024, something that has not happened in many years as China strives to become a major economic and industrial powerhouse. But the main reason for the decrease is not the addition of renewable energy resources, but rather a collapse in the country’s construction industry. After years of over-building, the chickens have come home to roost as China now has a glut of unoccupied or underused apartment and commercial buildings.

The lesson here is that emissions from cement and steel really are significant and must be reined in if the world is to have any hope of averting a climate catastrophe. Not only that, emissions from other essential industrial activities like aluminum production need to be addressed as well. For years we have concentrated our attention on carbon emissions and ignored the host of other atmospheric pollutants that threaten the ability of the Earth to sustain human life. That is a conversation few want to have, but which all of us must.

Have a tip for CleanTechnica? Want to advertise? Want to suggest a guest for our CleanTech Talk podcast? Contact us here.

Latest CleanTechnica.TV Videos

CleanTechnica uses affiliate links. See our policy here.

CleanTechnica’s Comment Policy