Sign up for daily news updates from CleanTechnica on email. Or follow us on Google News!

Since about 1980, China has built a few things. 500 cities. 46,000 kilometers of high-speed rail. 177,000 kilometers of highways. Tens of thousands of dams. Over 50 subway systems with over 10,000 kilometers of track. A lot of light rail systems. About 1.5 million kilometers of transmission lines. About 8 million kilometers of electricity distribution lines. 34 major sea ports. About 2,000 inland river ports. About a terawatt of wind and solar. About 240 major airports.

China’s not done yet, but it’s slowing down a lot. It has cities for all of the people likely to live in cities. The ghost cities that the west made such a big deal about are filling up. China knew that it had to get people out of subsistence farming and into much more fulfilling and productive work and built cities with full infrastructure and utilities to accommodate that before they were going to be full. It has a few more thousand kilometers of high-speed rail to build, but that’s filling in the gaps.

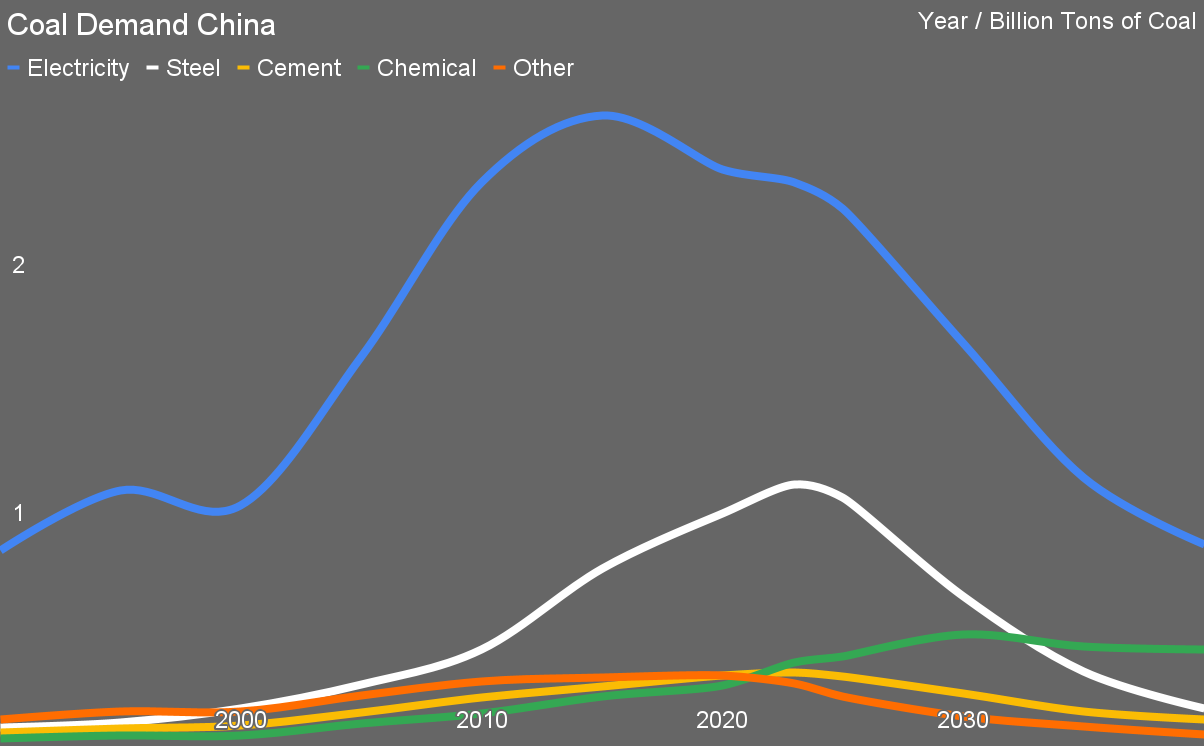

A thesis I’ve been articulating, not original to me, is that China’s demand for cement and iron is peaking and is going to drop substantially, especially for cement. Further, China’s coal fleet capacity may be high and increasing with last year’s approved plants, but the capacity factor will be plummeting with the 300 GW and increasing annual additions of wind and solar, and the occasional massive hydro dam like the Three Gorges and the absurdly huge 16 GW Baihetan Dam, which started generating in 2021 and will be fully commissioned in the mid-2030s.

China’s population has peaked. 65% of them already live in urban areas, and for the most part, there is housing already built for a lot of the rest. Rural resource extraction and construction is automating rapidly. Don’t believe me? Watch this video of heavy lift drones moving big solar panels to hillside solar farm installation points. Or this video of a massive swarm of heavy-lift spray drones putting products on crops in the country.

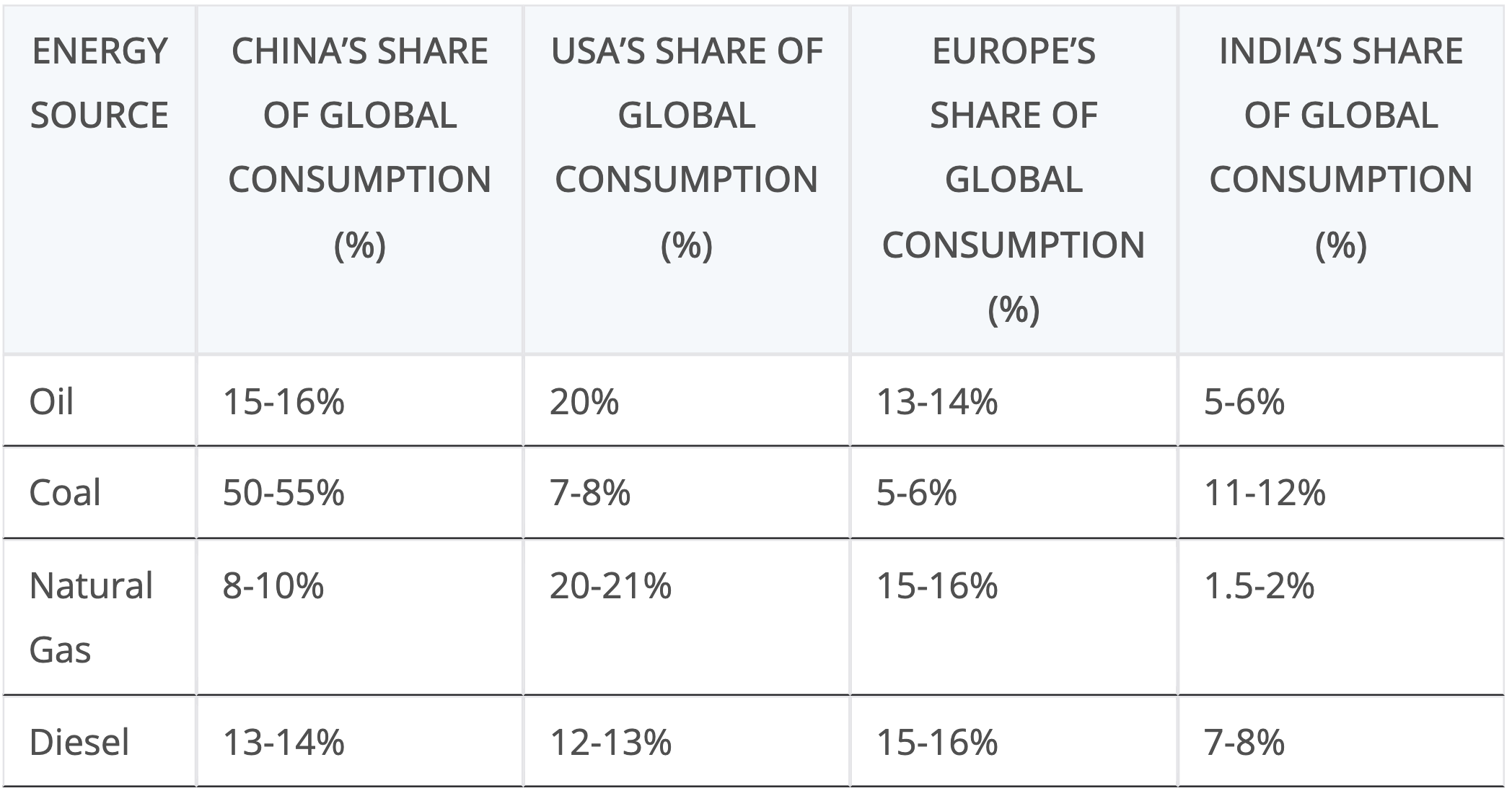

For a recent article on the deep, systemic, and structural, and usually ignored challenges to the United States decarbonizing, I pulled together the table above. For this assessment, I’ll look at a single number, the 50-55% of global coal consumption that occurs in China.

The biggest consumer of coal in China is electrical generation, consuming 50% to 55% of annual demand. As noted before, China, unlike the west, is rapidly expanding both electrical generation and electrical energy services, across transportation, heating, and industry. Coal burned for electricity in a mixed grid with the electricity used for end energy services is still lower emissions per energy use case than burning fossil fuels directly. China’s grid electricity carbon intensity per kWh has dropped to about what the USA’s was in 2011 even with their coal boom.

With the roughly 300 GW of wind and solar and increasing, renewable’s percentage of the electricity mix has been increasing rapidly. Over the next decade, the country is likely to deploy 4 TW of wind and solar capacity, generating perhaps 8,300 TWh annually. China’s total electrical generation in 2023 was 9,500 TWh. That doesn’t count the massive build-out of hydroelectricity or the much smaller build-out of nuclear generation. By 2040, China will have massively increased total electrical generation and the vast majority of it will come from low carbon sources.

In the first half of this year, China permitted only 10% of the new coal plants as the same period last year. Outside of a recent blip due to a heat wave, coal’s capacity factors and consumption for electrical generation are going down.

Manufacturing steel is the next big hitter, between coal for heat and coal for chemical reduction of iron, 20% to 25% of demand. 50% to 60% of China’s steel is used for infrastructure projects, and that’s slowing down outside of the 5% to 10% used for power generation. As I noted in my series on steel leading to my demand, supply, and decarbonization projection through 2100 — likely to be updated as I look at China’s demand more closely — China manufactures half of the steel used in the world, with the next biggest manufacturer, India, having only 10% of China’s production. Only 5% to 10% of steel in China goes into products for export. 30% to 40% of steel is used for manufacturing domestic products.

This year China banned new coal-fired and fed iron and steel facilities. The country is pivoting rapidly, as predicted, to electric arc furnaces. All of that domestic steel going into manufactured objects is showing up in scrap yards. China produced 260-280 million tons of scrap steel in 2023, and produces about 30% of its steel demand from scrap steel. That’s going to climb to US levels of 70% over the coming couple of decades, especially as steel demand for infrastructure plummets. Between significant new steel demand reductions and more steel from scrap through electric arc furnaces, coal demand for steel is going to plummet too.

China’s cement industry consumes 8% to 10% of the annual coal demand, firing the limestone calcining kilns with it. Unlike steel, cement barely registers in manufactured products and exports. As infrastructure demand dwindles, cement demand and attendant coal demand plummets.

The next big demand area is the chemical industry, with 5% to 7% of total annual demand. However, only 50% to 60% of the coal is burned for energy, with the remainder used as a chemical feedstock for ammonia, methanol, and other substances. There are emissions from coal as a chemical feedstock that would persist even if coal stopped being used as a source of energy, in the absence of carbon capture.

That’s another place where China has been making significant strides. One of my regular correspondents is Swarandeep Singh VP of ABB’s Energy Industries out of Sweden. For much of the past three years he was commuting to mainland China to build electrification into BASF’s latest integrated chemical facility. He shared a BASF chart with me. The facility, if powered by coal, would have produced 6-9 million tons of carbon dioxide annually. With the degree of electrification of the site and acquisition of renewable energy that’s in plan, the plant will emit about 1.8 million tons annually instead, 70% to 80% less than the coal version. It’s likely that the remainder of the emissions are process emissions as noted above, and BASF plans to address those in some way to create a net zero plant, if not a true zero plant.

Part of the story of China’s electrification lead is that it has electrified industry much more than the rest of the world, and the BASF plant is a single proof point on that. The 5% to 7% coal demand from the chemical industry will drop to half over the coming years, with only process emissions remaining.

Chinese households and buildings traditionally used coal for heating in northern China, but that’s gone by the wayside rapidly. It was a big contributor, along with coal generation plants in and around their northern cities, to the horrendous air pollution that used to plague the country. They started cleaning that up in the run up to the 2010 Winter Olympics, shifting domestic and commercial heating to heat pumps and electric stoves. Over half of the premature deaths due to air pollution were due to indoor air pollution, and that number has plummeted. Coal use for domestic and commercial heating has plummeted to being a rounding error in the last fifteen years.

Similarly, textiles, paper, and food processing used coal for energy in the past, but this was always a small demand area compared to the others and has also seen significant decline as China electrified energy supply in those sectors as well.

About a year ago, David Fishman of the China-focused Lantau Group predicted that 2024 would see peak coal in China, and I agreed then and agree now. Peak infrastructure is past and peak coal generation is past. The 50% to 55% of global coal demand from China is going to be cut dramatically in the coming years. But how much and how quickly?

To explore this, I went back to 1990 and pulled data every five years for total coal consumption in China. I developed percentages of demand areas based on the mix of use of coal for electricity vs other purposes for each of those years. Based on the trajectories of electrical generation and other demand areas, I projected the relative demand from different segments for each of 2025, 2030, 2035, and 2040.

The first obvious point from this is that despite the permitting of coal plants, actual demand for coal from electrical generation — per the data I have — has dropped. That’s a result of significantly declining capacity factors for coal generation, combined with the sunsetting and mothballing of older, higher emissions coal plants in China. Coal demand increases have come from cement, steel, and the chemical industry.

During this period, total electricity supply will continue to skyrocket. Actual energy demand will plummet for two reasons. The first is that the incredible energy demand of cement and steel will decline as the country’s demand shifts to manufacturing and industrial uses instead of infrastructure build-out. The second is that the country’s demand will plummet because electrified energy services are much more efficient than fossil fuel-provided energy services the vast majority of the times. This is true for process heat as well, as heat pumps will be used and provide an average of three units of heat for every unit of electricity.

Finally, renewably generated electricity does not waste the energy in fossil fuels. Burning fossil fuels to make electricity requires roughly three units of heat for every unit of electricity, but wind and solar farms don’t burn fuels so don’t waste that energy. Every MWh of wind and solar that’s built results in far more efficient overall energy demand.

The combination of electrifying everything — which China is leading the world on — and building renewables to power it — which China is leading the world on — leads inexorably to far lower primary energy requirements and a much more efficient energy ecosystem.

On that note, China burning this much coal for electricity for transportation, heating, and industrial electricity demand today means that it’s fairly easy to displace it with renewables. It’s much easier to decarbonize electricity that’s already being used in end energy services than it is to electrify end energy services. The outsized emissions from electrical generation are misleading.

Of course, this leads to much lower greenhouse gas emissions as well. Burning coal is responsible for 70% to 75% of China’s greenhouse gas emissions. Right now China’s coal emissions are in the range of 9.4 billion tons of carbon dioxide annually. Assuming this trajectory is close — and I’ll restate what I always say, that I don’t claim to be right, just less wrong than most — they’ll be roughly 3.5 billion tons in 2040. The rest of their economy will have continued to decarbonize at the current accelerated rate, so their total emissions will likely be in the range of 4 billion tons of carbon dioxide. This is nothing to write home about, still a very large number, but the trajectory indicates that very low greenhouse gas emissions by China are likely in 2050.

Meanwhile, there’s the United States. As my recent piece, Is The USA Becoming A Free Rider On Other Countries’ Climate Action?, pointed out, they aren’t significantly increasing electrification from the levels below Europe or China, and are in fact burning a lot of unrecorded energy behind the meter in shale oil extraction, so are likely declining in actual percentage of energy from electricity.

They have unique challenges for ground and air transportation due to the legacy of the post-WWII years when sprawl was federal and corporate policy, combined with a great deal of systemic racism. A combination of toxic marketing and loopholes in CAFE regulations has led Americans to consider multi-ton, slab-sided road yachts to be personal vehicles, while personal vehicles in the rest of the world usually don’t have four wheels, and when they do are comparatively tiny. Americans drive their monster SUVs and pickups far further every day and year than the rest of the world does as well, twice as far as Europeans. They drive them at higher speeds on the interstates much more often as well. The combination of much heavier vehicles driven much further and much faster means that they are much more expensive to electrify.

The unprecedentedly high tariffs and software bans on Chinese electric vehicles combined with an absolute requirement for electric road vehicles to solve their very high transportation emissions means that road emissions will decline much more slowly in the country than elsewhere in the world. The impetus to protect domestic industries which have been refusing to invest seriously in decarbonization and to ensure that the country is left entirely behind in the battery economy of the future has some limited merit, but from a climate action perspective it will be a significant hindrance.

The Jones Act and deindustrialization has left them without a commercial ship-building industry, with an expensive and small domestic battery industry, and no ability to buy electrified and dual fuel maritime vessels from abroad. Their methane emissions have skyrocketed and it’s systemic to shale oil, a major growth industry, so won’t be easily reduced. Their rail industry too is exceptional, fighting electrification tooth and nail while the rest of the world quietly puts up overhead wires and further decarbonizes that segment.

Their housing is sprawling, detached, and leaky due to zoning and building codes that didn’t care about efficiency, and is heated almost entirely by gas and oil because fossil fuel energy prices have been dirt cheap in the country and once again zoning and building codes didn’t care. Similarly, their industry outside of aluminum and steel is lagging seriously on electrification, once again because fossil fuels have been dirt cheap and there have been little to no federal or state mandates on efficiency or electrification.

And finally, while they managed to enact a loophole-riddled methane leakage price and a market mechanism on high global warming potential refrigerants, they are alone among the large economies of Europe, China, and India in not having a carbon price, a fundamental mechanism required to deliver economic incentives. In combination with the dirt cheap fossil fuels and refusal to apply other policy measures to increase their cost compared to electrification, the country’s citizens and businesses are just going to keep burning fossil fuels outside of cities and states that force them to do otherwise. As noted, only 3.5% of the USA’s population is in cities where bans on gas hookups for new buildings are in force, and there is near zero movement for retrofitting existing gas and oil powered buildings compared to European and Chinese focuses.

As I noted in the article, these significant road blocks to climate action are barely recognized among climate policy and strategy efforts that I’ve seen. The US transportation blueprint talks about mode-shifting to water without recognizing that the domestic fleet is old and rusting and that there’s no capacity to build more Great Lakes, Mississippi, or coastal ships, along with even lower ability to build electric drivetrains for them. The rail industry’s refusal to electrify and the federal government’s inability to do anything about it is not covered, as is the rail industry’s inevitable decline as the full third of their revenue from moving coal goes away, making the revenue per mile of track and hence available maintenance and transformation dollars plummet.

The intent to mode-shift people to walking, biking, and transit ignores that US sprawl has led to a situation where 92% of all weekday trips are by car because that’s the only way to get between places in the built environment in anything like a reasonable period of time for the vast majority of Americans. Walking, biking, and transit are luxuries of dwellers in some cities, not available to the vast majority of Americans where they live and work, and densification to address that is a multi-generational effort with no political will behind it. Europeans, by contrast, see 45% of weekday trips by car, with most people having the option of choosing other modes, and Asians only 30%.

Today the USA’s total greenhouse gas emissions are in the range of 6.2 billion tons of CO2e annually. That number is going to decline very slowly because they have, for better or worse, made themselves into one of the hardest to decarbonize countries in the world, and have fossil fuel consumption patterns per capita vastly higher than the major economic blocks of Europe, China, and India. This is without getting into the challenges of their strong fossil fuel lobby which is hindering climate action and supporting divisive politics at every turn, capturing politicians across the aisle, but especially among Republicans.

When asked what year would see the United States return to being the highest emissions country in the world, exceptional in a bad way, I dithered between 2035 and 2040 over the past few days. But this projection — once again, not right, just less wrong — makes it appear likely this will occur a bit earlier than 2035.

All of this makes me wonder what they are smoking in Washington that wunderkind economist Brian Deese’ suggestion of a Marshall Plan for clean energy developing nations is being taken seriously. It’s the height of arrogance that the country with the highest total emissions to date, the second highest emissions right now, the highest barriers to decarbonization, and the least credible trajectory for decarbonization thinks that the world needs more USA.

What the world needs is for the USA to enact a Marshall Plan for itself. It needs to urbanize and massively densify urbanization, abandoning sprawling suburbs to their own fates if they want to persist. It needs to cluster industries of the future. It needs to permit and build a lot of HVDC transmission, offshore wind, pumped hydro, and onshore wind and solar. It needs to seriously deregulate and streamline permitting of commercial, residential, and industrial solar. It needs to undertake a Manhattan project electrification of everything.

It needs to transform its educational system to deliver far more STEM graduates and far fewer charter school religious studies students, revamping and enriching its public education system. While it’s at it, it could revamp health care as well. Right now, the USA leads the world on expenditures per student on education and healthcare per citizen, yet trails the world in outcomes from education and healthcare.

The Chinese scientists and engineers that the USA depended on increasingly for its foreign student revenue, educational systems patents and royalties, and STEM competence in startups and domestic firms are streaming back to China and other parts of the world due to the increasing hostility and risks they are dealing with. The USA is facing a brain drain just when it needs a serious STEM influx, or even just to retain the brains it has.

This is not to damn the United States, but to issue a wake-up call to it. The country is on the precipice of being a global climate pariah, falling further and further behind a decarbonized world, being cast into being a gas station with an atomic bomb, as Josep Borrell, High Representative of the European Union for Foreign and Security Policy, describes Russia.

Good strategy starts with a hard-nosed acceptance of reality, as Richard Rumelt points out, and US domestic climate policies — I’ve read, assessed, and published regarding most of them — don’t start with reality, they start with mythology and aspirations. They are feel-good documents. Only starting based in reality leads to policies and action plans that will actually lead to positive outcomes.

Under the Biden Administration, massive increases of fossil fuel extraction, processing, and exporting have occurred, along with massive increases in burning fossil fuels to power it and leaking methane from it. Meanwhile, exactly zero offshore wind farms have been commissioned during this period. Exactly zero miles of new HVDC transmission have been put into operation during this period. Exactly zero pumped hydro or hydro electrical generation facilities have gone live during the Biden Administration. Onshore wind and solar capacity additions over the Biden Administration were fairly flat, not accelerating upward as they are in China.

The United States is congratulating itself, breaking its arm patting itself on the back, when it should be wondering what the heck went wrong and trying seriously to fix it. Deese’ arrogance is far from unique. When China’s Belt & Road Initiative has most Central American, all South American, and many eastern Europe states in its membership, building transmission, railroads, and electrical generation globally, over three-quarters of countries globally, the USA’s primary response is $1.6 billion in a bill to promote global disinformation about the BRI and China. (It passed the House recently with very strong bipartisan support, indicating that it’s likely to get through Congress easily.)

To be clear, Biden inherited a country that had abandoned industrial policy — he was a senior member of government during the 1980s, 1990s, 2000s, and 2010s when this abandonment occurred — and had significantly rising income inequity (once again, on his watch as a senior member of government), and finally woken up to the reality that the path was toward economic and societal disaster. The Biden Administration is trying to reverse 40 years of strategically detrimental policies, and that’s a very positive thing.

He was vice president when the Affordable Care Act was brought in, a terribly compromised solution to try to bring quite a lot of Americans out of medical bankruptcy, but the USA is unique among developed nations in having longevity declining, so clearly it wasn’t remotely enough. He inherited a country that had deindustrialized to an incredible extent, ceding manufacturing of all kinds, mostly to China. Once again, while he was a senior member of the US government.

He inherited a government that has spent 40 years giving tax cuts to the rich instead of housing, education, and healthcare to the masses. Yes, again while he had power, authority, and influence, as is true of the vast majority of powerful Democratic politicians at the federal level. They aren’t a young group, and while Republican policies are clearly and subjectively more damaging to the USA, many Democratic policies were just less bad versions of Republican ones, and many Democratic politicians voted for Republican policies.

Biden inherited a country coming out of COVID, suffering from the complete failure of the Trump Administration to address it, getting back on its feet and into its SUVs and pickup trucks. He inherited a country riven by such a degree of irrational partisanship on the right that a significant percentage still think Trump won in 2020, and the ones who believe that are expecting political violence this year.

There are clear signs that the Administration’s policies and actions are leading, slowly, to positive movement on some aspects of climate change, domestic industry, and income inequity. Turning a massive ship that’s been steaming in the wrong direction for 40 years isn’t quick. Turning a massive ship when half of the country wants to turn it to steam into the past is challenging.

But on climate, the United States isn’t moving nearly quickly enough, nor with remotely a sense of reality of the magnitude of the challenges facing it. China doesn’t appear to share those problems. The result is inevitable. As China’s emissions plummet in the coming years, the United States will see much slower emissions decline and the lines will cross again.

Have a tip for CleanTechnica? Want to advertise? Want to suggest a guest for our CleanTech Talk podcast? Contact us here.

Latest CleanTechnica.TV Videos

CleanTechnica uses affiliate links. See our policy here.

CleanTechnica’s Comment Policy