Support CleanTechnica’s work through a Substack subscription or on Stripe.

In October 2025, the federal government officially designated the four-unit SMR build at Ontario Power Generation’s Darlington site as a “Major Project” and invested $2 billion through the Canada Growth Fund, alongside $1 billion from the provincial Building Ontario Fund, signalling that the federal government views the SMR programme both as a national-industrial priority and a pillar of Canada’s clean-power strategy. This upfront funding and symbolic anointment embed the SMR scheme at the core of Prime Minister Carney’s climate-industrial agenda—tying his legacy to its success and subjecting his broader ambitions to the reactor’s performance.

Ontario once led the world in nuclear engineering. The province built its grid around CANDU reactors designed, manufactured, and operated by Canadians. Those heavy-water machines provided decades of reliable electricity and created thousands of high-skill jobs. They also anchored a domestic supply chain that made Canada one of the few countries with full nuclear sovereignty. Now, as the world turns toward flexible, low-cost renewables, Ontario is making a different bet. With Mark Carney’s backing and the provincial government’s enthusiasm, it is building the first GE Hitachi small modular reactor at Darlington. It is a decision that will look visionary to some today, but in a decade it will look like a strategic error.

Carney’s ambition to build a clean, secure industrial future for Canada is genuine. His economic credibility and climate focus give him the moral authority to act. But in aligning himself with an American-owned, first-of-a-kind reactor technology, he has made a choice that will come back to haunt him. The project promises jobs, energy security, and innovation, but it delivers higher costs, greater complexity, and new dependencies. The evidence is already clear. Ontario Power Generation’s Darlington site is the province’s largest single employer, and the refurbishment program for the existing reactors is providing steady, high-paying work. The new SMRs are not needed to sustain that prosperity. What they will bring is financial exposure and an energy mix less aligned with what Ontario actually needs.

Darlington alone employs roughly 15,000 people directly and indirectly in a region with only 70,000 workers. Those jobs are secure for decades through ongoing refurbishment and operations, with the current CANDU reactors expected to be extended to 2065, an unprecedented 80+ years. Average wages are among the highest in the province. It is by far the largest and best paying employer around. Adding four small modular reactors does not create a new employment base. It diverts billions of dollars toward a first-of-a-kind nuclear experiment that will be built by foreign technology vendors and managed under unfamiliar regulatory frameworks. For the region, this is not an economic development project. It is an engineering gamble wrapped in the rhetoric of innovation.

The GE Hitachi BWRX-300 is a light-water boiling reactor that bears little resemblance to the CANDU systems Ontario’s nuclear workforce knows intimately. It requires enriched uranium, not natural fuel. It has a fixed refuelling cycle, not continuous on-power refuelling. It depends on U.S. supply chains for core components and fuel assemblies. Ontario’s nuclear professionals, from control-room operators to maintenance crews, have spent their careers mastering CANDU systems. They will have to relearn an entirely different technology under a regulatory regime still being defined. The Canadian Nuclear Safety Commission has no operating precedent for this design, and its licensing process must be harmonized with the U.S. Nuclear Regulatory Commission. The result is a project that combines first-of-a-kind technical risk with first-of-its-kind regulatory uncertainty.

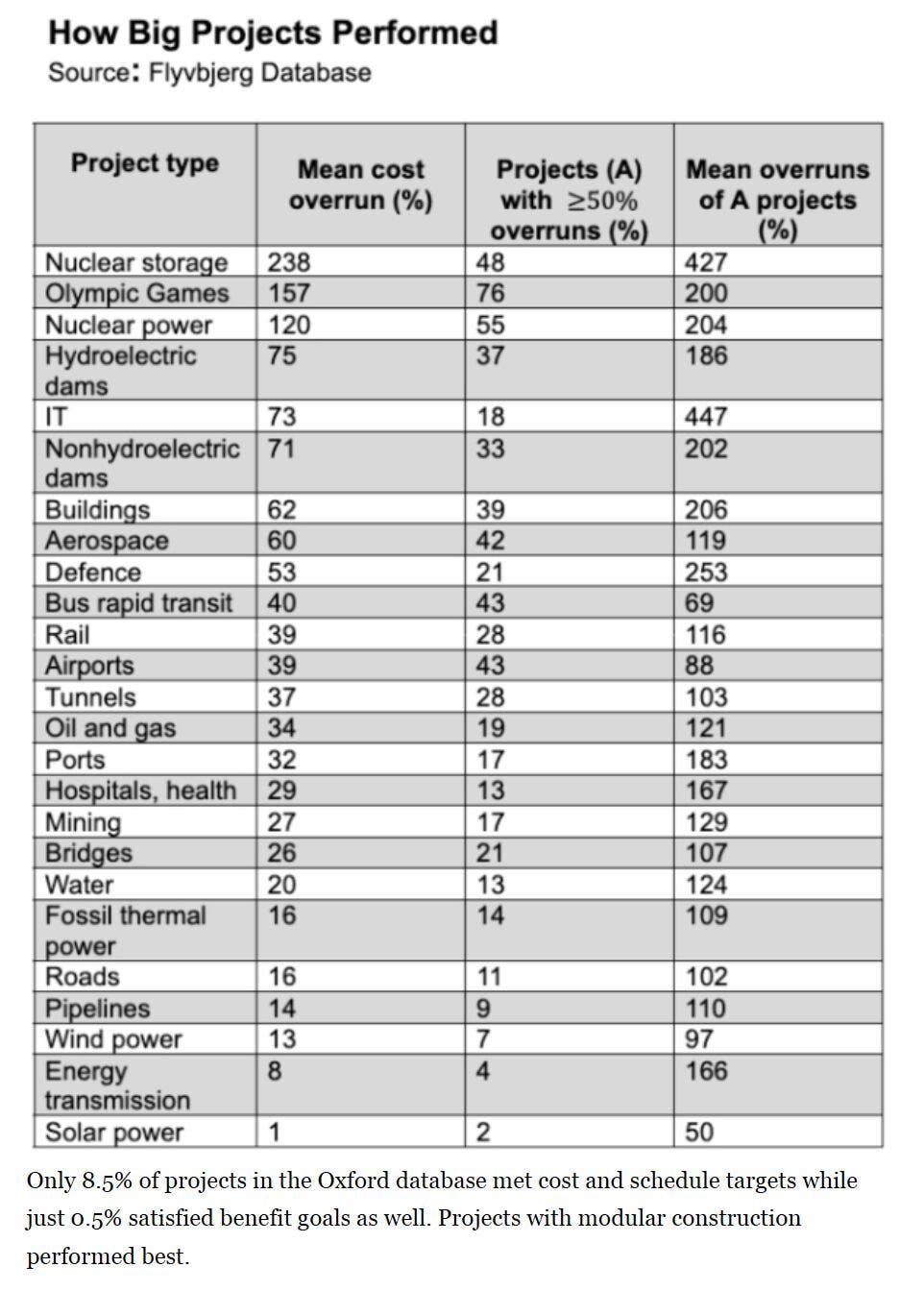

Bent Flyvbjerg’s megaproject database—now in the tens of thousands of cases across sectors—shows nuclear among the worst performers for cost and schedule reliability, with a dedicated nuclear new-build reference class of roughly 194 projects used in recent risk analyses. From that record, reference class forecasting (RCF) gives decision-grade uplifts: at P50, add about +67% to capital and +40% to schedule; at P80, plan for roughly +202% capital and +104% schedule. In practice, you take Ontario’s inside-view budget and timeline for the Darlington BWRX-300, apply the chosen P-level uplifts to produce an out-turn cost and commercial-operation window, and size contingencies, financing, and tariff impacts from those outside-view figures—not from internal estimates that history says are systematically optimistic.

The financial consequences will be significant. Nuclear megaprojects are consistently among the worst performers in cost and schedule. Even small reactors face the same challenges: long construction timelines, bespoke components, and escalating financing costs. Reference-class forecasting of global nuclear builds suggests P80 cost overruns above 200% and schedule slips beyond 100%. That means Darlington’s first SMR, now budgeted at about six billion dollars, could easily cost more than eighteen billion and arrive half a decade late. The smaller physical footprint will not save it from the same economic gravity that has plagued every other nuclear build of the past half century.

Ontario is already spending heavily to make its existing nuclear fleet work in a modern grid. Baseload inflexibility forces the system operator to curtail renewable generation and dump surplus power at a loss to neighboring markets. The Independent Electricity System Operator has acknowledged the problem and is investing in flexibility services—expanding natural gas plants, procuring battery storage, and reforming market structures—to balance inflexible supply. Those gas plants in Napanee, Windsor, and St. Clair will emit millions of tons of carbon dioxide each year. The paradox is inescapable: Ontario is adding more fossil generation to manage more nuclear generation. A province that could have achieved the same reliability through cheaper renewable firming is choosing to make its grid dirtier and more expensive.

The economics of that choice are stark. Firmed wind and solar already deliver electricity at around $60 to $100 per MWh in Ontario. The risk-adjusted levelized cost of energy for small modular reactors is expected to range between $160 and $370 dollars per MWh, well above the publicly stated $106 to $146 per MWh, even with low public-sector borrowing costs. Ontario could triple its renewable generation and build large-scale storage for less than the cost of one first-of-a-kind SMR project. Instead, it is locking itself into decades of higher prices and higher emissions.

There is also the geopolitical dimension. The GE Hitachi reactor is an American design, subject to U.S. export controls and governed by U.S. intellectual property law. Canada is currently a preferred destination for nuclear technology under U.S. Part 810 regulations, but that status is a policy choice, not a treaty right. A future administration in Washington could alter the rules with little warning. Fuel supply is similarly exposed. The United States has banned imports of Russian low-enriched uranium, tightening global supply. Ontario’s SMRs will depend on that same market. The result is a future in which Canada’s nuclear baseload relies on the stability of U.S. politics and fuel markets—an uncomfortable position for a country seeking energy sovereignty.

It is striking, almost perverse, that while Canada and Donald Trump’s U.S. administration are locked in full-blown trade war—with tariffs, threats of annexation and bilateral negotiations abruptly terminated—Ontario is still committing billions to build a nuclear programme under U.S.-owned vendor control. In 2025 President Trump imposed sweeping tariffs on Canadian exports and abruptly ended trade talks over a provincial advertising campaign. Yet at the same moment Ontario is embracing a reactor design owned and controlled by a U.S. firm, subject to U.S. export-controls and fuel-supply dependencies. The contradiction is clear: when U.S. policy towards Canada has turned hostile, Ontario is doubling down on U.S. nuclear technology rather than minimising strategic risk.

AtkinsRealis, formerly SNC-Lavalin, sits in the middle of this project as a major engineering partner. The company has cleaned up its governance after the corruption scandal that damaged Justin Trudeau’s government, but its legacy remains politically sensitive. Its CANDU Energy division is the steward of Canada’s indigenous nuclear technology and the heart of its nuclear expertise. In the SMR project, AtkinsRealis is no longer the technology leader nor is it the nuclear technology expert; it is an engineering contractor supporting a foreign vendor. It’s 800 or so CANDU experts don’t have any history or expertise with the GE SMR or the underlying nuclear generation approach. That reintroduces political risk. Carney, who has watched governments fall over procurement controversies, should recognize the hazard of relying on a firm with that history in a project of this scale. One of Trudeau’s strategic missteps was not paying sufficient attention to the SNC Lavalin file until it bit him politically, and Carney is now exposed to the firm as well, although to a lesser degree.

Ontario’s grid does not need more nuclear baseload. It needs flexibility, dispatchability, and affordability. Nuclear already supplies more than half of the province’s electricity, and that dominance creates structural inefficiencies. Strategically, Ontario should aim to reduce nuclear’s share below 40% while expanding renewable and storage capacity. The province’s geography, hydro reservoirs, and interties make that possible. Adding more nuclear capacity—especially in small, expensive, and inflexible units—moves in the opposite direction. It increases surplus baseload generation, depresses export prices, and requires fossil backup. It is a system-level error disguised as an innovation.

Projecting forward to the mid-2030s, the pattern is predictable. Costs will climb as the first unit faces engineering surprises. Subsequent units will be delayed as lessons are absorbed. Gas-plant emissions will rise to cover flexibility shortfalls. Ratepayers will see steady increases in electricity prices. Renewables and storage will continue to fall in cost but will be slow to expand because public capital is tied up in nuclear construction. Ontario’s energy independence will decline as American suppliers, regulators, and investors gain influence over its most critical infrastructure. This is not a scenario born of pessimism. It is simply what happens when the past decades of nuclear project data are applied to new promises. Canada is not China, where they have managed to at least stabilize costs of new nuclear reactors instead of seeing them rise.

Carney’s intentions are not in doubt. He wants to decarbonize, to reindustrialize, and to demonstrate that Canada can lead in clean energy. But the Darlington SMR decision does not achieve those aims. It substitutes national expertise with imported technology, trades affordability for prestige, and deepens dependence on a volatile neighbor. It ignores the system-level economics of renewables and the existing structural advantages of Ontario’s grid. In the end, it may produce a working reactor, but at a cost measured not only in dollars but in opportunity lost.

Ontario’s nuclear history is a source of pride, but it should not be a constraint. The province has everything it needs—hydro, wind, solar, storage potential, and engineering talent—to build a modern, flexible, low-carbon grid without another nuclear megaproject. Choosing to build GE Hitachi’s small modular reactors instead will burden Ontarians with higher electricity costs, higher emissions, and a dependency that weakens national sovereignty. It is a decision that Carney and the province will come to regret, not because their goals were wrong, but because their chosen means could not deliver them.

Sign up for CleanTechnica’s Weekly Substack for Zach and Scott’s in-depth analyses and high level summaries, sign up for our daily newsletter, and follow us on Google News!

Have a tip for CleanTechnica? Want to advertise? Want to suggest a guest for our CleanTech Talk podcast? Contact us here.

Sign up for our daily newsletter for 15 new cleantech stories a day. Or sign up for our weekly one on top stories of the week if daily is too frequent.

CleanTechnica uses affiliate links. See our policy here.

CleanTechnica’s Comment Policy