Sign up for daily news updates from CleanTechnica on email. Or follow us on Google News!

In my regularly iterated Short List of Climate Actions That Will Work, there’s a big broom: Price Carbon Aggressively. In the maritime shipping world, it would be a big trawler net that scoops up emissions regardless of technology, allowing the market to figure out the cheapest way to achieve decarbonization.

The International Maritime Organization (IMO) has figured that out. What’s the IMO? It is an agency of the United Nations established in 1948 to develop and maintain a comprehensive regulatory framework for shipping, encompassing safety, environmental performance, legal matters, and maritime security. Officially coming into existence in 1959, the IMO has played a crucial role in setting global standards for the international shipping industry. With 175 member states and three associate members, it ensures the industry’s sustainability and efficiency on a global scale.

The IMO’s track record on climate change isn’t illustrious, frankly. It took them a long time to get beyond lip service, although they have typically been leading compared to comparable aviation agencies. For example, it was only in 2021 that the IMO embraced well-to-wake emissions as the standard. Prior to that, they were focused on tank-to-wake, leaving lots of room for the ammonia, methanol and LNG industries to push themselves as low-greenhouse gas alternatives to traditional bunker fuel.

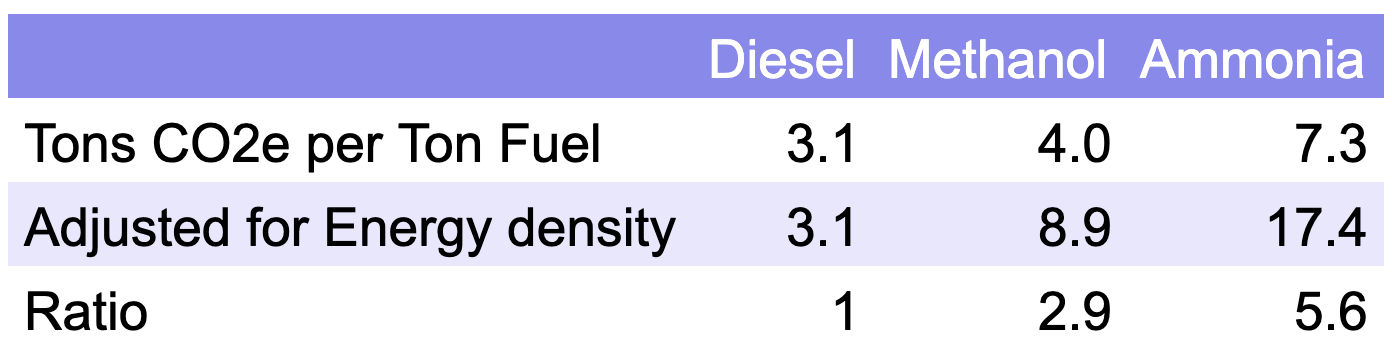

To be very blunt, the ammonia and methanol industries rode a very large crude carrier through that loophole in the past 15 years, pretending that they were lower carbon because their tank-to-wake emissions were much lower than legacy maritime shipping fuels like resid and very low sulfur fuel oil (VLSFO). The workup above is one I did a year ago as part of my ongoing assessment of maritime shipping decarbonization, based on data from those industries, governmental studies and peer-reviewed material. Well-to-wake, unabated ammonia and methanol are three to six times as emitting as legacy maritime shipping fuels, far from a win.

When pressed, the industries asserted that they would clean up those pesky well-to-tank emissions and further that they would be just as cheap, trying to get the shipping industry locked into their products as fuels with expensively retrofitted ships. Maersk is likely the big loser in this as they’ve committed more than anyone else to it, which is unfortunate as their early and strong climate commitment means that they have settled on an expensive alternative that likely won’t scale. However, Maersk did wisely hedge with dual-fuel ships.

LNG, liquified natural gas, is a different beast. It only manages 30% tank-to-wake emissions of carbon dioxide, so it’s clearly not a long term solution, yet hundreds of vessels have been built or retrofitted to burn it since 2000. For LNG tankers, that makes sense as boil off needs to go somewhere, and into engines is better than into the atmosphere. LNG, after all, is mostly methane, which is a very high global warming potential gas. According to the IPCC Sixth Assessment Report, methane’s global warming potential is 81 over a 20-year period and 27 over a 100-year period, highlighting its significant short-term impact on climate change.

It kind of makes sense for passenger ferries and cruise ships, another big segment, as it doesn’t stink nearly as badly as resid or VSLFO when it’s burned, with a lot less particulate pollution as well.

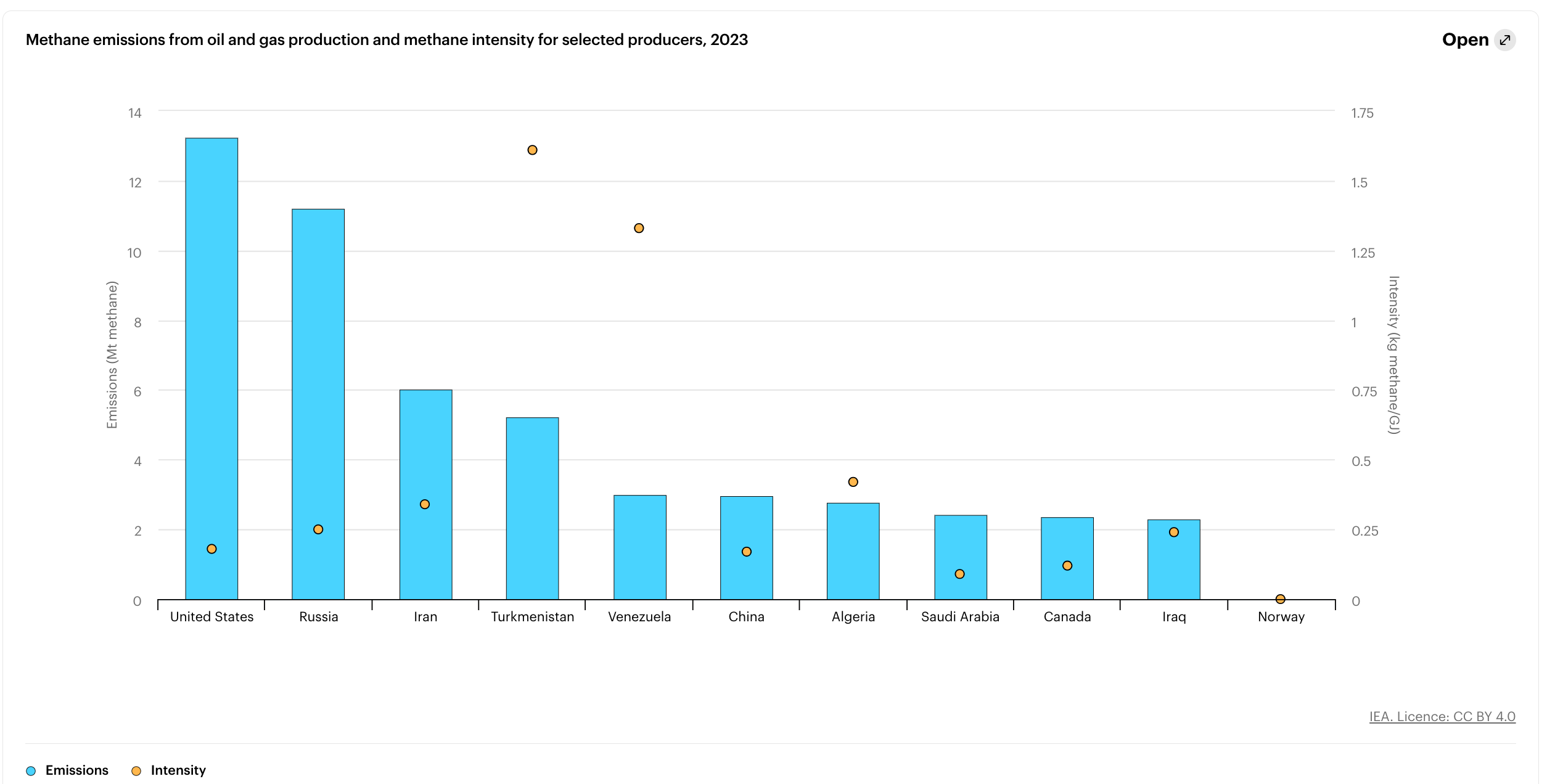

But once again, well-to-wake belies tank-to-wake, and there’s a tank-to-wake kicker. Let’s start with well-to-wake. Most LNG ships, the biggest LNG-for-power consumers in the shipping sector, originate from major LNG-exporting countries, including Qatar, Australia, the United States, and Russia. These aren’t countries which have done a good job containing fugitive methane emissions in their extraction, processing, and distribution supply chains.

The United States has the worst methane emissions from its oil and gas industry in the world. The chart above undoubtedly underrepresents them, as it’s based on the US Environmental Protection Agency’s lowball figure of 1.4%, when studies have been showing 3% to up to 9% in some cases. To be clear, shale oil is the big culprit in the segment, as natural gas isn’t the point of shale oil, so they have been venting or flaring massive amounts of unmarketable natural gas as a waste byproduct for a couple of decades. But leakage from US natural gas fracking, extraction, processing, storage and distribution is high as well.

Even if it weren’t, if say the world’s natural gas industry was as well regulated and careful as Norway’s, engines that burn natural gas don’t burn it very well. When I was facilitating an EU-Canada methane emissions reduction session in Calgary with government, industry and academic participants earlier this year, Shell’s representative admitted — without any apparent sense of irony — that testing had determined that the engines they burned methane in to power their facilities were the worst sources of leakage and that they were rapidly turning to electric motors instead.

In the maritime industry, the International Council on Clean Transportation dropped a depth charge with the results of its FUMES (Fugitive Methane Emissions from Ships) study which measured LNG ships smokestack emissions of methane for a couple of years. They found that the slippage rate — the percentage of methane that went up the smokestack unburned — was much higher than had been thought. While assumptions had been a still bad 3.1%, the study found 6.4% of methane was just vented to the atmosphere.

Just the FUMES study finding made LNG shipping higher emissions than resid or VLSFO shipping. Combined with the well-to-tank emissions, it’s much worse. LNG at least had the advantage of being comparatively cheap, but when no climate benefits are being realized, that’s faint comfort. LNG fuel is greenwashing.

The promise from the three industries was, of course, that they would be synthesized from green hydrogen and captured carbon dioxide (as necessary, as ammonia doesn’t require carbon). However, that’s always been an economic dead end, as while hydrogen can be green, it can’t be cheap, despite the collective hallucinations of a rather large set of stakeholders over the past several years. Boston Consulting Group admitted this late last year, saying that the ‘consensus’ of €3 per kilogram green hydrogen by 2030 was unrealistic, and that €5-€8 (likely the high end) was going to be the reality. BNEF reported that the average green hydrogen deal that reached final investment decision had a price point of €9.5 per kilogram in 2023. No one in the investment community believes green hydrogen will be cheap any more.

There is a pathway for methanol to be a biofuel, just substituting biologically sourced methane instead of fossil methane for methanol manufacturing. That’s what Maersk is doing, but supplies are constrained and manufacturing a lot more methane in anaerobic digesters which tend to be distributed and leakier isn’t a climate solution either.

There are obvious solutions which the industry has been resistant to, but there is finally movement on this front. As I noted a year ago, there’s a clear channel for decarbonizing maritime shipping, but shipping firms haven’t been in it. That channel is batteries for shorter shipping distances, which is to say all inland shipping, most of short sea shipping, all national waters ship movement, and all ship movement in ports, with biodiesel for longer distances. Biodiesel blends are already being bunkered, we are already manufacturing 70 million tons of biodiesel annually (and wasting it on ground transportation, which will electrify) and shipping is going to decline as fossil bulks are reduced.

Batteries will be cheaper than burning fuels, and anywhere that electric drivetrains can be used they will be, just as with every other segment of transportation and industry. They are much simpler, much more efficient, and much lower in maintenance costs, as well as having instant torque, very consistent power, approaching zero health hazards for crew, and no pollution of any kind during operation. Hybrid long-haul ships are an obvious solution, but one the industry has been resisting.

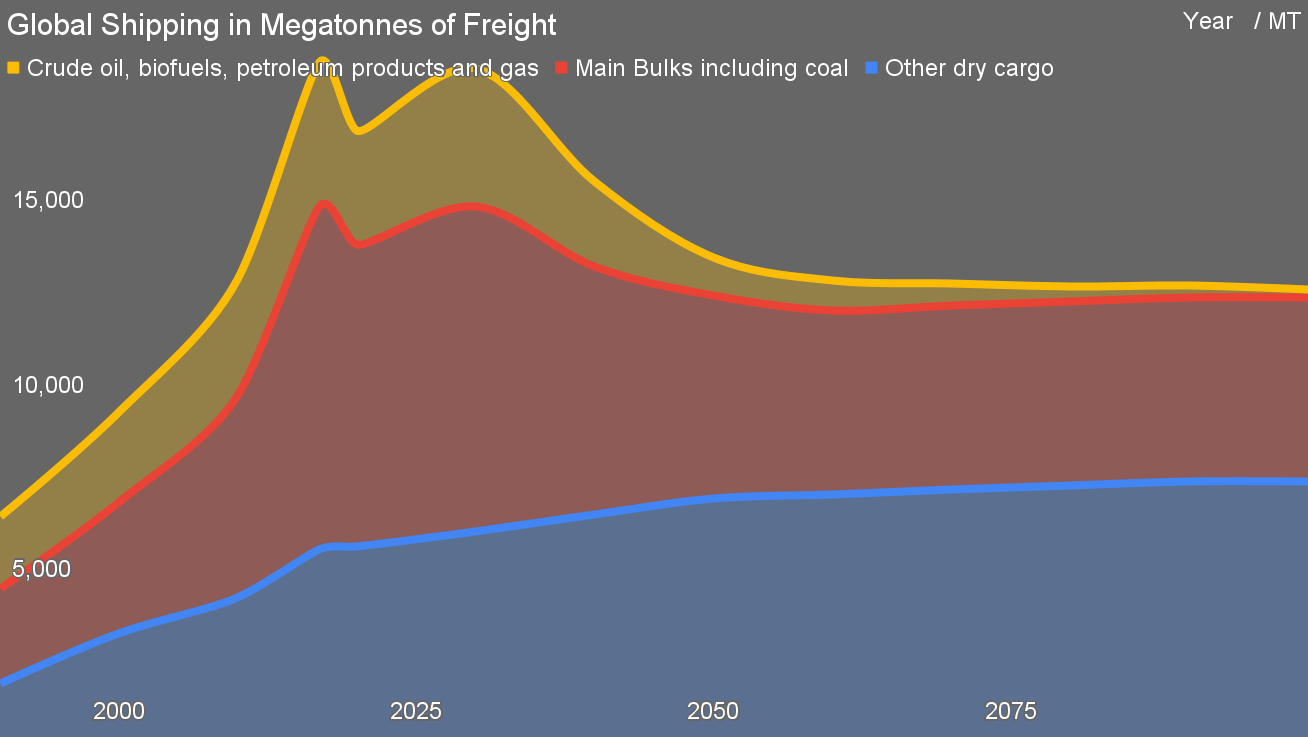

While shipping is 3% to 5% of global emissions, depending on where you draw the boundaries, the problem is going to diminish, not that the IMO accepts that. Fossil fuels account for 40% or so of bulk oceanic shipping, and as coal, oil, and gas burning for energy diminishes globally in the coming decades, so too will bulk shipping. To a lesser degree, the 15% of so of bulks that are raw iron ore will tend to be processed closer to mines with renewable electricity directly or via hydrogen turning them into iron and possibly even steel for shipping in smaller tonnages. China is at the end of its massive industrialization and infrastructure boom, so it won’t need as much steel.

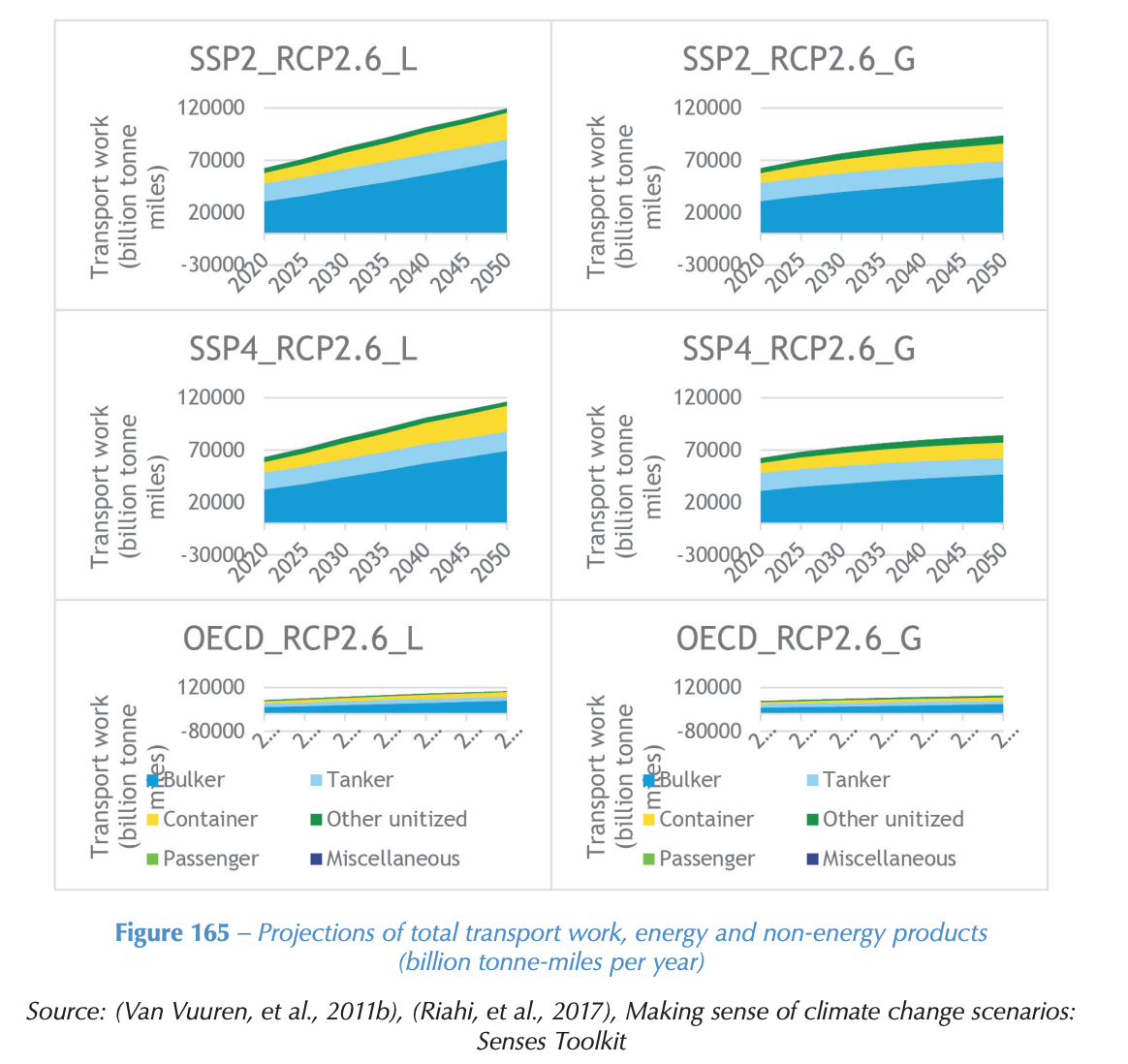

This is the official set of scenarios for maritime shipping the IMO leans on for its greenhouse gas studies. (The variance in total tonnage between my projections and the IMO’s is that I include inland, short sea, and deep water shipping, as I unified and normalized a bunch of data sets to get a complete picture.) You’ll note that it’s devoid of relationship to reality about bulk shipping. And to be clear, everyone knows this. Last year, there was only one very large crude carrier on order, when typically 25 to 35 are on order to deal with end of life replacement of the over 900 VLCCs plying the oceans, never mind growth. When I deal with maritime shipping firms in Europe or Malaysia, for a couple of examples, the bulk carriers are trying desperately to figure out what they will replace their revenue with (pro tip: not bulks).

But there is finally movement. As noted earlier, the IMO moved to well-to-wake life cycle carbon assessments as a requirement in 2021, something that’s undoubtedly causing heartburn in the ammonia, methanol, and LNG industries which were hoping for a massive new market for their products. And in 2023, the IMO agreed to put carbon pricing in place on shipping globally. What that entails, and what it looks like, is a big question.

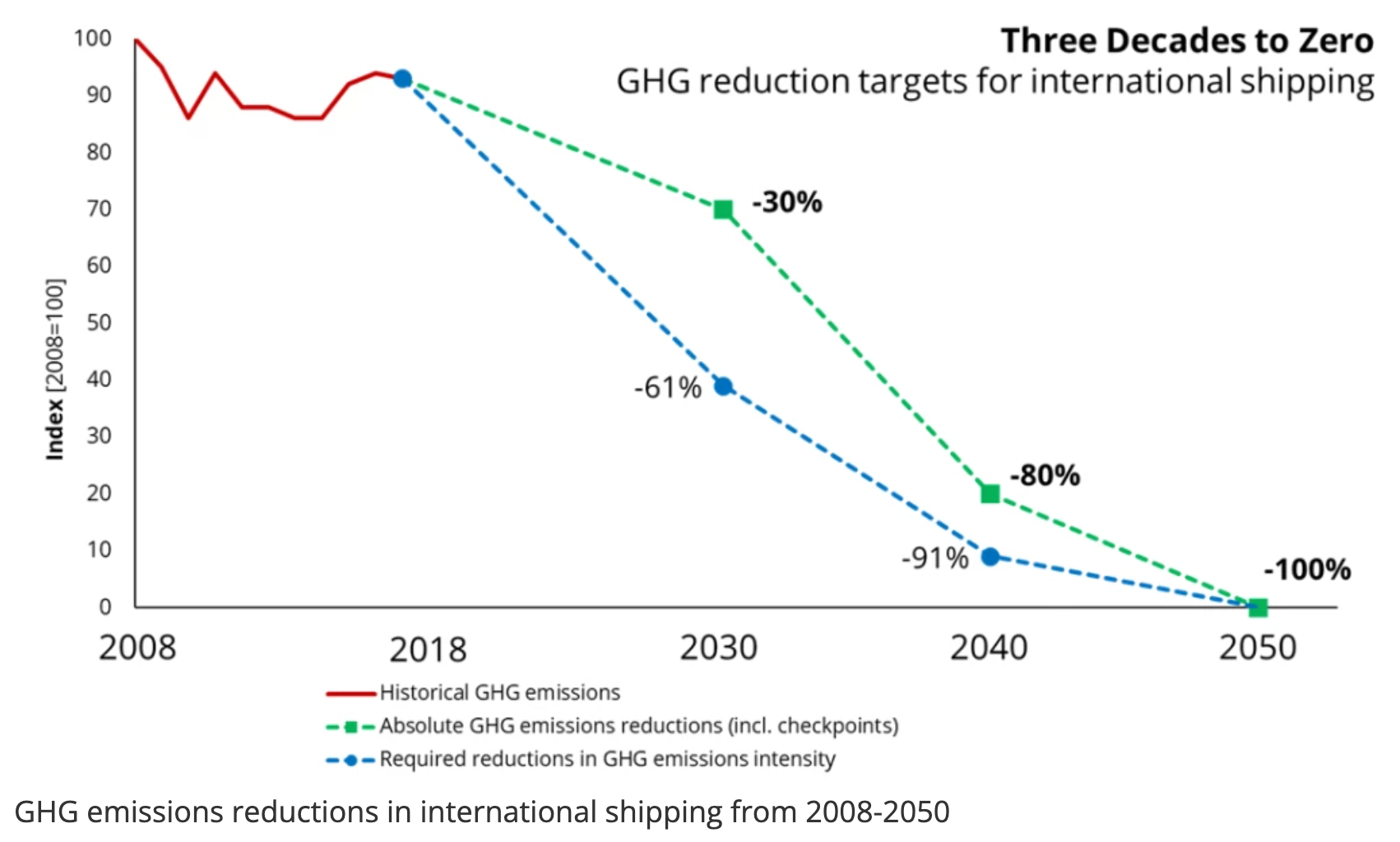

The bottom dashed line is GHG reductions with voluntary carbon offsets. Recent rumblings indicate that the IMO, like everyone else, can no longer pretend that voluntary carbon credit schemes have any credibility in a serious decarbonization strategy, so expect to see this downplayed in coming years. The good news is that its absolute emissions line is based on high growth of maritime shipping, so it’s going to be easier to achieve than it asserts.

A global carbon price on maritime shipping is a key lever, one of the few that will make any real impact in the space. Voluntary efforts like Maersk’s are nice, but relatively uncommon. While biodiesel is a lot cheaper than proposed synthetic fuels, both in cost per ton of fuel and in the lack of capital expenditures for bunkering and engines that can run LNG, methanol or — sailors take warning — ammonia, it’s still more expensive than VLSFO. As always, nothing is cheaper than long buried biomass that’s been converted over geological time into convenient, dense liquids when we can use the atmosphere as an open sewer.

But it has to be high enough to make a difference. An analysis by European economists found that a price point of $40 per ton of emitted carbon dioxide or equivalent wouldn’t make much of a difference. A study by DNV — which does good work when it’s not being paid by fossil fuel industry stakeholders to tell porkies about hydrogen — found that “a carbon levy of $150-$300 per tonne on shipping would result in the lowest impact on global economic growth in 2050 if the revenues were disbursed only to states that were most vulnerable to the impacts of climate change.”

Contextually, the $150-$300 range puts it into realistic carbon pricing range. The current, relatively harmonized EU budgetary guidance and US / Canadian social cost of carbon is around $190 per ton, rising to close to $300 per ton in 2030 and slowly increasing from there.

The point on vulnerable states is a key concern. Poor countries would pay a larger ratio of carbon pricing to GDP unless money flowed to them from the carbon price. Innumerable countries and organizations are modeling this to figure out what the least economically impactful approach will be to carbon pricing with the highest GHG reductions and the lowest social inequity. It’s a non-trivial exercise and special interests of all types are trying to make the case for what is best for them of course.

The climate impact and social equity concerns mean that at present, a majority of the member countries of the IMO support carbon pricing. However, that doesn’t mean that they are the most powerful countries. Big economies, including China, Russia, India, Brazil, and Saudi Arabia, oppose it. Two of those are petrostates, so can be counted on to oppose any climate action. A bit of good news is that the IMO, while a UN agency, is not subject to the Security Council veto. Russia, bizarrely as a rogue state, still occupies one of the permanent security council seats and can veto anything out of the UN, but not out of the IMO (or the International Council on Civil Aviation aka ICAO, the aviation-oriented sibling to the IMO).

China, Brazil, and India tend to view climate action through the lens of needing to bring their teeming masses out of poverty and into relative affluence as a balancing requirement. Policies which the west wants to impose on them after creating the majority of the climate change problem with historic carbon dioxide emissions are considered deeply unfair. China and India are both complaining to the World Trade Organization regarding the EU’s carbon border adjustment mechanism, as a related concern.

However, China has a regulated carbon market on heavy industries and is going to expand it and increase the price over time. India is in the midst of trying to get a carbon price in place, but far too much of it is for voluntary carbon offsets. Carbon pricing is spreading, but unevenly and too slowly.

The IMO is thrashing out the details of the maritime shipping fuel carbon price this year and will publish it in 2025. The intent is that it will go into effect in 2028. Despite the lack of a veto by Russia, very big power blocs are working to prevent or soften this. How that will turn out is an important question for climate action.

But remember, the IMO’s official position is that maritime shipping is going to increase a lot, including bulks. Even if it doesn’t get carbon pricing right, the problem is going to diminish, not increase.

Have a tip for CleanTechnica? Want to advertise? Want to suggest a guest for our CleanTech Talk podcast? Contact us here.

Latest CleanTechnica.TV Videos

CleanTechnica uses affiliate links. See our policy here.

CleanTechnica’s Comment Policy