Sign up for daily news updates from CleanTechnica on email. Or follow us on Google News!

Under the auspices of the India Smart Grid Forum, the think tank founded as an umbrella organization over India’s 28 state utilities to provide thought leadership, share leading practices, and bring international insights to India, I’m delivering bi-weekly webinars framed by the Short List of Climate Actions That Will Work. With the glories of online recordings and AI transcription tools, it’s relatively easy to share both the transcript and the slides that I used, so I’m making a habit of it.

Most recently, the seminar topic was carbon pricing. For those who prefer talk-talk to read-read, here’s the recorded video of the presentation and discussion.

Reji Pillar (RP): Good morning, good afternoon, good evening to all the participants and it’s my pleasure to welcome you all for this 6th edition of this webinar series created by ISGF. The contents are the results of 15 years of hardcore research by Michael Barnard and each topic is important in the net zero journey for each country. Today we will be talking about how the carbon pricing is going to help and affect towards zero transition in different countries. More focus in Michael’s slides will be on India. As many of you know, we have a carbon market by and large already. It was expected to be launched sometime in January this year, but it got delayed. We believe in the second half of this year, a carbon market will be operational in India.

And as my colleague had already mentioned, the previous five-webinar video link including the presentations are available on ISGF YouTube channel and the link will be posted on the comments box. And you can paste it, you can take it from there. So, and this one, today’s webinar. We’ll be able to circulate the PPT and the video over the weekend or latest by Monday. So over to you, Michael.

Michael Barnard (MB): Thank you Reji. And as always, thank you to Reji and ISGF for giving me the opportunity to assist in what small way I can with India’s essential journey through the intersection of affluence and climate action. It’s tremendously important that India get it right, just as it is important for every other country in the world. So let’s cast our mind back about 100 years. There’s a British economist named Arthur Pigou, and he was looking at industry and he was looking at transactions and looking at markets, and he noticed something interesting about them. Despite the claims of them being perfect mechanisms, there was a bunch of stuff excluded from stuff that he called externalities.

Originally he was focused on positive externalities, like the people who had a position on a river that enabled them to take advantage of the river’s water for their processes and have a water wheel and stuff like that to provide them power for their mills, versus people who didn’t have that position. They had a positive externality, something that they got for free that enabled them to be more competitive. As his thinking progressed, he realized, oh, well, there’s also negative externalities, things that are not priced into the equation of costs in a transaction which actually do have a societal cost. So those negative externalities are not being charged in the cost of the transaction.

He was looking at pollution at the time, he was focusing on industry, and he was realizing that even then, in 1820, there were very clear health problems with significant pollution from heavy industry, and those were being borne by people who were not the people who were owning the factories. He presented the idea of negative externalities and said, start to think about mechanisms for putting those into transactions. And over time, they had been adopted.

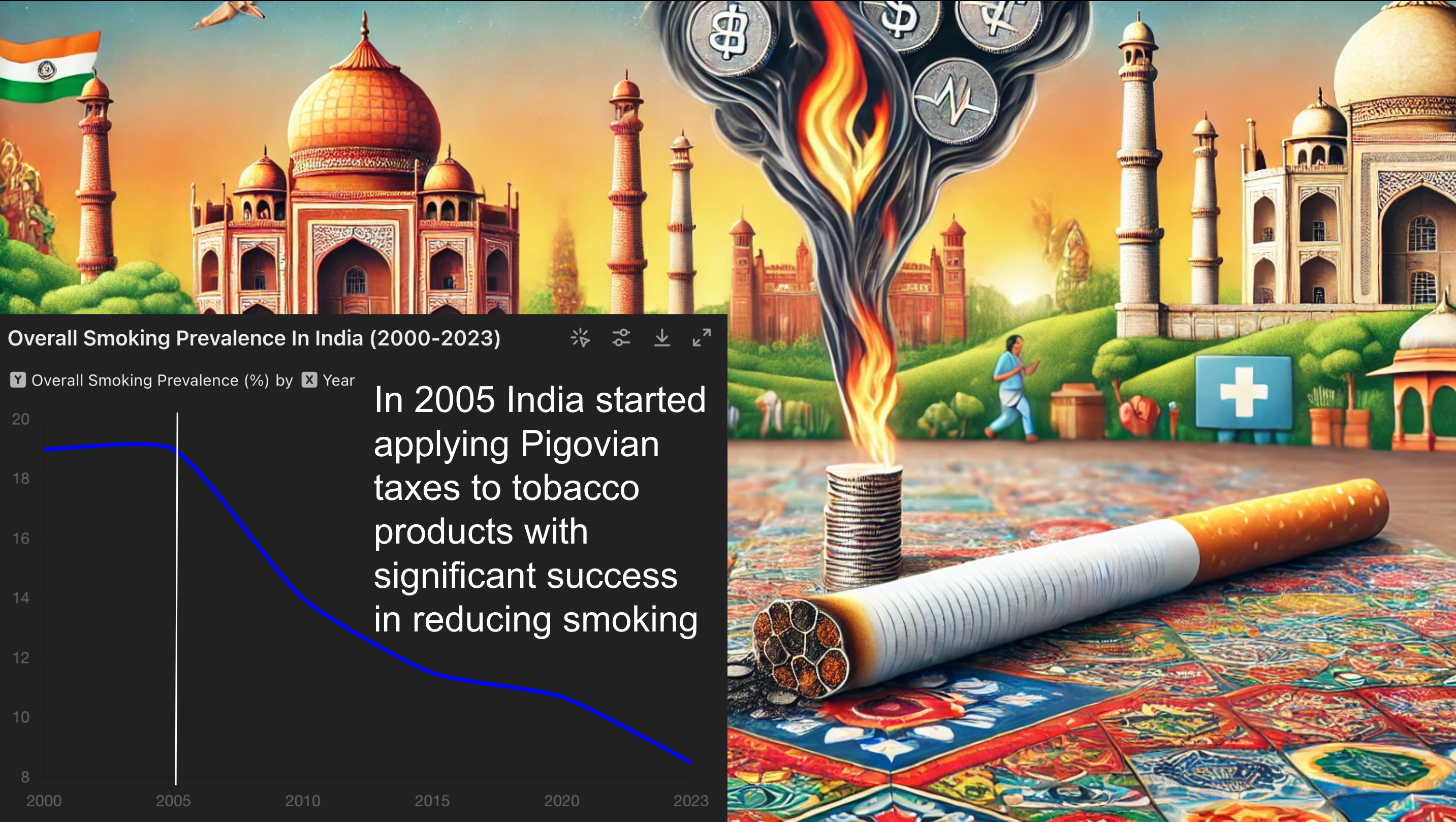

In the Indian context, about 20% of India’s adults were smokers as of 2005. As you look across the time, in 2005, India started applying Pigouvian taxes to tobacco products. What’s happened is that’s been a big part, along with communication, education. But those Pigouvian taxes started reducing the incidence of smoking.

It’s a fairly clear transactional thing. Once cigarettes weren’t cheap, as they increased in price, people made different decisions. And along with education, with the health impacts and the other problems, India’s smoking rate has gone down sharply in the past 20 years. We can see that now India is following the footsteps of other countries which started applying Pigouvian taxes to smoking and alcohol. Sin taxes are one of the ways it was described, and that led to changes in behavior. This is something which has a history globally. It has a history in India. As we move forward, we have to think about the implications of this for other types of activities.

This isn’t to say, by the way, that markets are bad. I’m a strong market capitalist, but I’m not a free market capitalist. I’m a regulated market capitalist. Markets are really good at a whole bunch of things, and then we have to make them not be bad at the things that they’re bad at. One of the things markets are bad at are negative externalities. Market transactions don’t care about negative externalities unless we, through regulation and policy, make them care, and then we can price that stuff in.

Let’s talk about a carbon price and how it works from a consumer perspective, because there’s this odd belief. An executive who took me to Latin America for a leadership role a decade or so ago reached out to me two or three years ago and said, Mike, what’s happening with this carbon price in Canada? Is it working? Is it good policy?

He is an affluent person living in an affluent part of Toronto, and he was looking out, and he just didn’t see his neighbors behaving differently. They were still going on vacations, they were still buying cars, they were still doing all the same things that he thought that they were doing in the past. He didn’t see them making different choices. I said to him, Ilya, they are making different choices. You’re just not seeing them. For example, if somebody had an air conditioner retrofit, you’d see they had a new central air conditioner, but you probably wouldn’t see that the central air conditioner was actually a heat pump, which replaced their gas furnace and their central air conditioner with one unit. You see that they have a new car in the driveway, but now there’s 90 brands of electric cars in the road, so you probably just don’t recognize that some of these cars are electric.

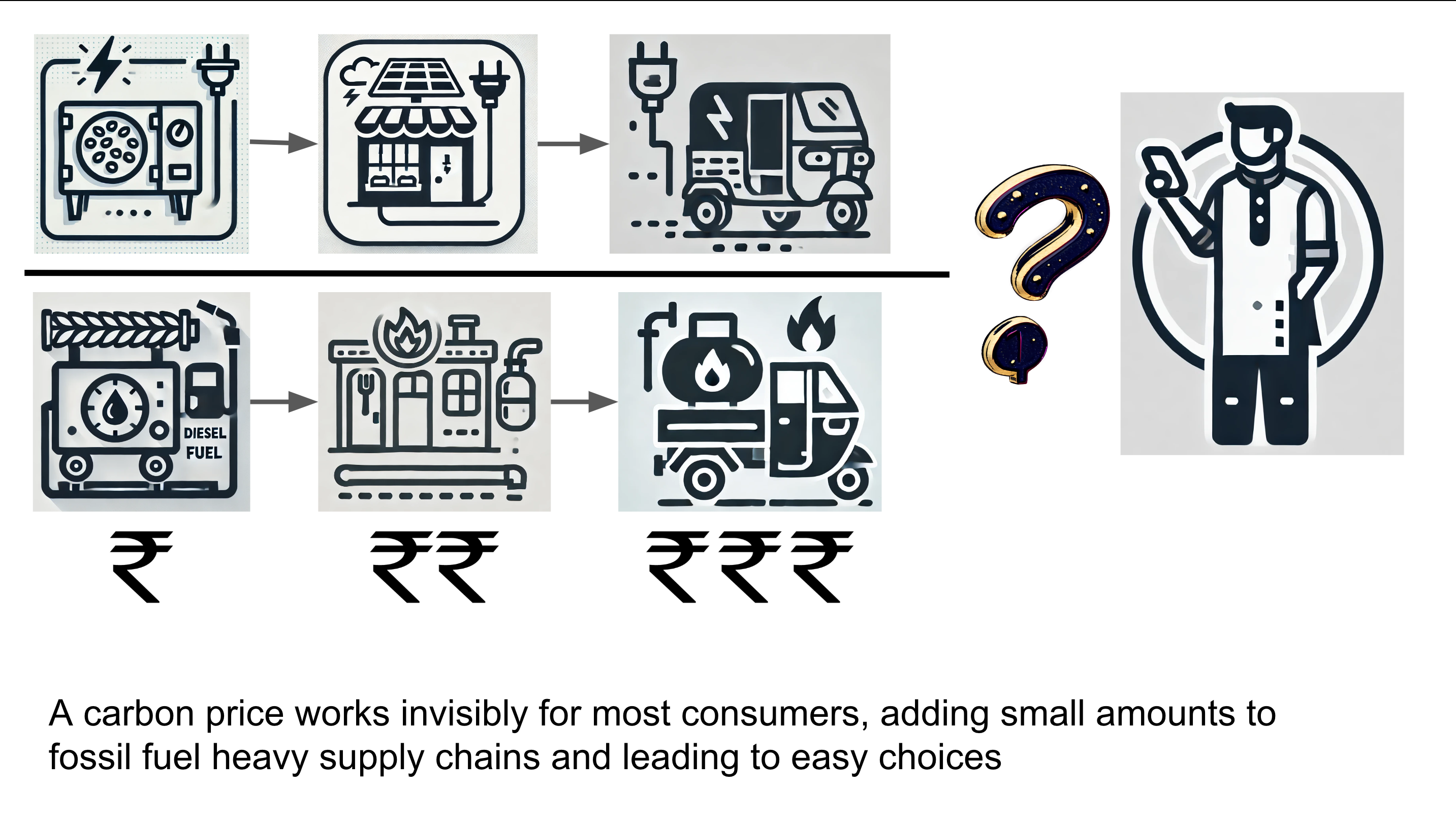

These are just choices that people make. They get to a certain point, it informs their decision as they move along. Then there’s the second really invisible part of carbon pricing, in this case, food preparation that’s electrified to a restaurant that is electric to a delivery vehicle that is electric to a consumer sees very low carbon prices. But fossil fuel-powered food processing to a fossil fuel-powered restaurant, to a fossil fuel-powered delivery vehicle, would see little bit of extra cost in each of those transactions, leading to the point where the fossil fuel supply chain has a higher price point for its end product or lower profits.

The consumer sitting there with their smartphone ordering food will say, oh, well, I know that the food from this place is just great and it costs a bit less. I’m just going to take that. They don’t think about why one costs a little bit less versus another one. We see this invisible process through the supply chain that leads to greater competitive advantages for decarbonized supply chains versus competitive disadvantages for fossil fuel supply chains. That’s as it should be. The only reason that fossil fuels are cheap is because we use the atmosphere as an open sewer and cause global warming. Also air pollution, childhood health problems, etcetera.

Most of the time, for most people, the carbon price doesn’t change their daily behavior. They still order food, they still go out for entertainment, they still do things. But more and more, the choices of moving around are electric. I know in India, for example, enormous numbers of the auto rickshaws are now electric. People have the auto rickshaw as an opportunity and they don’t think about it. They get an auto rickshaw to get to someplace and it happens to be electric and just isn’t a thought for them.

As we move forward, we start thinking about what that implies for the economy, and we see that every supply chain starts being that way. We see that industry, the industry which starts manufacturing cement with an electric supply chain and electrification as much as possible, and better insulation and a whole bunch of other things emits less carbon dioxide and other greenhouse gases, and as a result has a competitive advantage.

The one that stays on fossil fuels over time becomes less competitively advantageous. This is something that’s an over time process.

What happens with a well designed carbon price is that it is something where there is certainty, economic certainty, for the participants in the economy. And by that I mean the best designs of a carbon price are ones which go up with acknowledged amounts over time, so that businesses and organizations can make strategic plans with some economic certainty. They can make choices today that they know will pay off in the future by avoiding a high carbon price and by having competitive advantages.

Canada, as an example, has that type of planned annual increases with high visibility to and certainty about what the carbon price will be each year. Organizations which have high fossil fuels in their supply chain can look at that and say, my product has to be this much more expensive. They can test that with their customers and say, that’s not going to work. And they say, how do we reduce this part of our cost structure? How do we avoid this carbon price? That’s relatively easy to do.

To compare and contrast, the EU does not have a stepwise increase target price. What they have is a carbon market with allowances in some cases and a diminishing cap over time that leads to a knowledge that the amount of carbon the industries can emit is going to decrease. It’s a less certain price signal. But the EU has also provided budgetary guidance to organizations that are operating in Europe and incidentally to other areas as well, which I’ll get to in a bit. That budgetary guidance says, this is how you should price carbon in each of the years through 2050. And so, for example, in 2030 right now, it’s about almost $200. In 2040, it’ll be almost $300. It starts to be a fairly significant price per ton of greenhouse gases. That regulatory signal of the cost of carbon enables people to put that into their business cases and project their cost structures and design their supply chains so that they avoid those prices.

The people who are paying attention and do that are more economically competitive. The people who don’t do that and ignore it or pretend it’s not going to happen or just are ignorant of it, become less economically competitive. What this leads to is people who align with where the market is going, the priced negative externalities will be more economically competitive, more likely to survive in this transition, because this is a significant transition, it’s an unpopular subject, but there will be winners and losers. Most fossil fuel vendors are going to be losers in this process, and hence the reasons they’re fighting it tooth and nail in many cases.

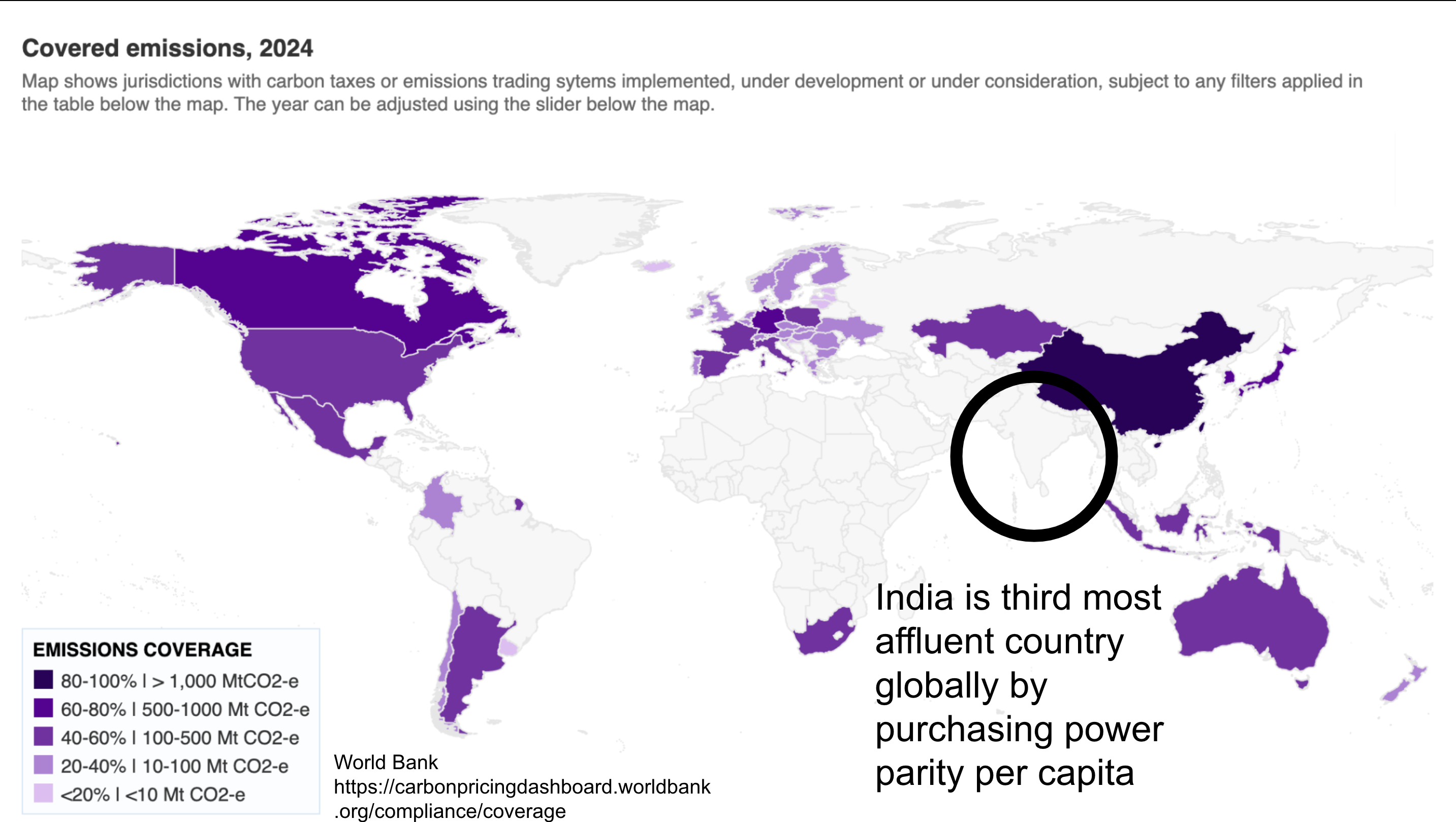

Let’s talk about where there are carbon prices. I’ve mentioned the EU and I mentioned Canada. This is an indication of this particular view from the World bank, is how much of emissions are covered by the emissions trading scheme. So there’s some interesting stuff on here.

One, you’ll notice how dark China is up here. Well, China has a fairly low carbon price, but it’s on some of their most emitting industries, and it’s a cap and trade model. It’s not a stepwise increase. It’s a market like the EU’s. It’s not a voluntary market. Voluntary versus regulated involuntary markets is a key distinction when it comes to carbon pricing. Voluntary markets are feel good markets and they don’t incent significant change. People participate in them because they are in an industry where marketing green qualities is something that gives them economic advantage, but there’s no value in it. And frequently, the voluntary carbon markets price carbon incredibly low. If the price of carbon, a carbon credit in a voluntary carbon market is one to $2 us per ton, that’s not the right price point.

There’s an inequity problem related with voluntary carbon market scope, which I’ll touch on in a second. But China, I call out, because it’s one of India’s great competitors as well as having a carbon market. India manufactures and sells things that China also manufactures and sells. China has a carbon market while India doesn’t.

As we look across the United States, you’ll see actually that it has two carbon pricing systems. But what that is they have two greenhouse gas systems. They don’t have one for carbon dioxide. It’s a very odd situation in the United States. Hopefully, it won’t get too much odder. But in December 27 of 2020, in the last days of the Trump administration, they brought in the American Innovation and Manufacturing act. It was a bipartisan bill supported across the house, and it included allowances and a market mechanism for high global warming potential refrigerants, HFCs.

This was aligned with the intent of the Kigali Amendment that was signed in 2016 in Rwanda. The amendment to the Montreal Protocol on Substances That Harm the Ozone Layer. As a reminder, the ozone layer is healing because we got rid of CFCs. Unfortunately, the HFCs we replaced them with were almost as high global warming potential. And so now we have to replace the HFCs. But the United States, as of 2021, actually had a greenhouse gas market, which was completely overshadowed by events. I only found this out recently.

They also have, starting in January of this year, a methane price on leaking, methane emissions, methane being another high global warming potential gas. The United States, because of the shale oil revolution and the fracking revolution, combined with very lax regulations on pipelines and facilities for gas and oil has become the world’s largest leaker of methane from their fossil fuel industry. It’s quite extraordinarily high, and it’s wiped out all of the gains they’ve received from not burning coal. But as of this year, they’re starting to price that at $900 us per ton of methane. That’s equivalent to $36 per ton of carbon dioxide. Because of that high global warming potential difference, the United States actually has two carbon pricing systems.

One of them, methane, is a priced one, which will go up in 2025, and then it’ll go up again in 2026. In 2026, it’ll be $1,500 per ton. That’s actually quite a reasonable economic signal. The industry in the United States is working to eliminate the ones that they can eliminate, which is, frankly, not all of them.

Canada actually has one of the most encompassing carbon markets in the greenhouse gas markets, in the sense that it covers all of the greenhouse gases and has since its inception eight years ago, six years ago, the amount that means it covers carbon dioxide, it covers methane, it covers refrigerants, and it covers a handful of other things, to the point where it’s all signified and down to specifically a carbon dioxide or equivalent measurement.

But that said, there’s the nuance of implementation. There are specific industrial emitter programs, like TIER in Alberta and others, that have done specific things for specific industries which are equivalent to the national carbon price, but more aligned to the realities there. We have probably five different mechanisms right now for dealing with different segments of the economy. We have some exclusions as an exclusion.

In the eastern part of Canada, a lot of homes still use fuel oil, and fuel oil is quite expensive. The eastern part of Canada is not the rich part of Canada. It’s part of the poorer parts of Canada. We have homes with people who are in our bottom 40% of income and affluence who can’t afford to transform. They are burning oil for heat because that’s what the house was built with, and don’t have the wherewithal to rapidly transform. And oil heating is the highest carbon emitting form of heating, so they’re being hit with high carbon prices as a result. Big kerfuffle. We’ve given them three years without being priced for carbon. And we’re incenting, providing other incentives, economic incentives, to move to heat pumps, so that when they return under the carbon pricing scheme, they will be in a low carbon pricing situation. This is the kind of stuff we have to do as we work through the ramifications of actually pricing carbon to protect the least affluent society from the implications of them. Certainly this has been part of the dialogue in India. Is the concern about a carbon price being regressive as opposed to progressive? But there’s more to say there.

The EU has the highest carbon price in the world. It got to over $100 US per ton a couple of years ago. The invasion of Ukraine by Russia and the energy crisis led to the the entire region of 28 countries leaping ahead in terms of decarbonization. They have implemented vastly more efficiency measures. Their heat pump deployments are very high. They’re starting to do a lot of electric vehicle stuff. They’ve done a lot of work on efficiency and they built a lot of renewables. And all of a sudden, their economy has decarbonized quite substantially.

Now, an interesting side effect of that is because it’s a market, not a stepwise, the carbon price went down. It got down to around $60 us per ton from its high, and now it’s back up around $82-$83 because they decarbonized rapidly and then people didn’t need to buy the carbon credits nearly as much. A lot more people had decarbonized their stuff. Some of that is masked by some economic challenges in these places, but it’s a fascinating tale of what’s happening with the different mechanisms.

It doesn’t surprise you that Australia is there, but look at Indonesia, another neighbor and an emerging economic powerhouse. It has carbon pricing in multiple parts of its economy already, and it’s likely to grow. South Africa also has carbon pricing. Argentina has carbon pricing. Mexico has carbon pricing. This is something that is sweeping across the world.

All of North America has variants of carbon pricing. That’s a massive economic block. All of Europe has carbon pricing. Massive economic block. China has carbon pricing, another massive economic bloc. And of course, the affluent nation of Australia has carbon pricing. This is an indicator that this is where the world is going. And there’s really interesting concerns there from an equity perspective.

One of the things that becomes important is that as some nations create carbon pricing, what they realize is if they’re pricing carbon domestically and importing goods from countries which are not pricing carbon, they can have border leakage. Border leakage refers to people in the domestic market just turning to high emissions products that are cheaper, because once again, the negative externality is not priced and the atmosphere is being used as an open sewer to the detriment of everybody.

Because the products are cheaper, they are seeking that economic advantage of a cheap product in their supply chain. That means that the carbon border, the carbon price is not being paid by one person versus another. And so we have carbon border adjustment mechanisms, CBAMs, starting up to prevent that leakage. Basically, goods imported to a country that has a carbon price at the border, at the point of importation, there’s a declaration, a requirement to assert the amount of embodied carbon in the product, scope one, two, and increasingly scope three emissions, and then that is added as a tariff or duty on the product as it enters the country. That means that it is competing on a level playing field with domestically manufactured products around climate pricing.

This probably didn’t used to matter to India, because in 1980, India was not a trading nation per se. It was a relatively small portion of the economy. But India has been liberalizing and becoming part of the global economic community to a startlingly large degree since then, which is part of the reason for increasing affluence in India. Except for a bit of a dip through 2010, now it’s back again in 2023. It’s now up to 50% trade to GDP ratio. And what that means is that while you trade relatively little with the EU, you do export a lot to the United States and you do a lot of trade back and forth with China.

Now the EU has a carbon border adjustment mechanism, which is going to be priced as of 2026. What that means is that they’re reporting now, anybody exporting to the EU now is reporting upon their carbon emissions in preparation for 2026, when they’ll start paying for their carbon emissions. There’s a scale through 2032 of increasing amounts of those things being priced so that third parties like India or China will slowly see that burden and will slowly become equivalently treated to European countries. It’s not immediately at the same price. It ramps up over time to once again give more economic certainty to third parties or their strategic stuff.

But there’s a little known detail once again out of the United States. The United States was in discussions with Mexico and Canada early in the Biden administration about a North American carbon border adjustment mechanism. The United States almost had a carbon price, a domestic carbon dioxide price to go with their HFC market and their methane emissions price. They didn’t get it through that time. But it included a carbon border adjustment mechanism. It was sold as an anti-China trade bill. But people in the United States who really don’t want to price carbon because they make all their money from coal, certain senators who shall remain Joe Manchin, they are in the Democratic caucus, and they refuse to put it even forward for a vote.

But it’s inevitable. The United States already has two greenhouse gas pricing mechanisms. It’s going to get the third. At some point. The United States exports a lot of stuff to Europe and vice versa. Europe’s carbon price border adjustment mechanism will impact all American organizations exporting to Europe. And so they’ll say, we have to adjust for this.

And as I showed with the previous map, carbon pricing is spreading fairly rapidly. It’s a clear, easy mechanism, especially not the voluntary ones, but the involuntary ones, the ones that are imposed by regulation with higher price points. That’s going to be the way of the future. Everybody’s going to do this in some way, shape or form, because once again, treating the atmosphere as an open sewer harms everybody, including the most vulnerable countries in the world. Disproportionately. The United States has the affluence to get around some of the impacts. Europe has the affluence to get around some of the impacts. Many other countries do not have the affluence to adapt easily or inexpensively, relatively inexpensively compared to GDP to that.

So India’s a trading nation now not what it was in 1980, and trade is going to be seeing carbon border adjustment mechanisms. The thing about a carbon border adjustment mechanism that’s important is they recognize carbon pricing in the exporting country. So Canada, when we export to the EU, all of our products have already seen a carbon price, which is quite reasonable, and that carbon price is a significant portion of the EU’s carbon price. At this point, we’re about two thirds. What that gives us is the opportunity to say, well, we’ve already paid two thirds of that. We’re only going to pay the last third. So their Canadian products, because they’re already driving that decarbonization pathway through their supply chain, exporting to the EU has a competitive advantage over countries which have not already applied a carbon price.

And China having a carbon price, firms exporting to the EU can deduct the carbon price where it’s applicable for the products, where it is applied to the EU and the United States. And North America almost had a carbon border adjustment mechanism, and I suspect we will. Again, we’re going through this weird political thing, just as all nations are. But it’s getting that direction. The implications are too high for us not to price this negative externality and deal with it.

In that context, I like to call out the competition between China and India. You both have industries, heavy machinery is one example, construction vehicles is another example, where you have firms which are exporting globally and are respected globally. As we look at that, China has two increasing competitive advantages over India, which India should be paying attention to.

The first is they do have that carbon price. So as carbon border adjustment mechanisms enter the equation, China will be prepared for that. The second, though, is something that’s difficult to see unless you look at the statistics, and that’s that China is winning the race to the electrified future. This is a data set I assembled for this discussion. In 1980, they had a lower percentage of their energy as electricity, and that was true until 2005. India was progressing upwards on electrification, and then in 2005, China started accelerating its electrification, and now it’s significantly more electrified as an economy than India is.

The title of this series is electrify everything everywhere, all at once. The point of electrification is that it’s much more efficient. So even if fossil fuel electricity is used, the end product is lower carbon debt. The more you electrify in terms of manufacturing processes, heat delivery, transportation, the more efficient and lower carbon everything is. And the more renewables you build, it’s a virtuous circle, because the renewable electricity is low carbon, and you’re using low carbon electricity to deliver stuff, your carbon debt drops tremendously.

Now, at this point, people are looking at the numbers saying, oh, well, China’s only 10% ahead, except that it’s not quite like that, because electrification is so much more efficient. 30% electrified doesn’t mean that China has 70% to go, but only has a third of 70% to go if their economy was stable, if they weren’t still growing. The reason I say that is because an electric end to end chain is three times more efficient in terms of delivering useful energy. They don’t have 70% to go, they have 25, 22% to go. They have to build more stuff, more renewables, which they’re doing, but they only have to build 22% more energy to deliver the same economic value as they are delivering today, whereas India, at 20%, has to do quite a bit more. Every percentage extra gain in that degree of electrification is strongly advantageous.

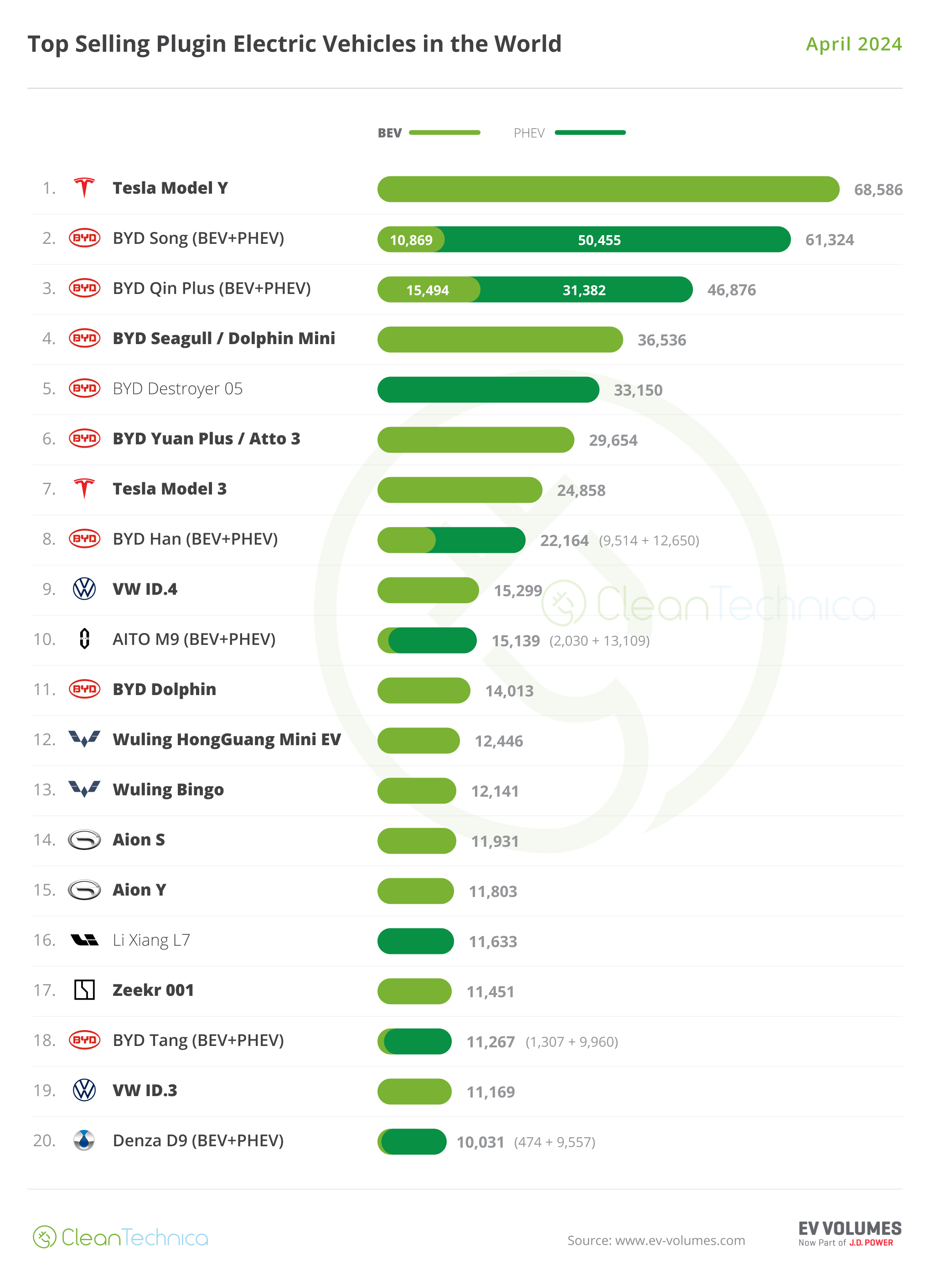

One of the things I’ve been saying to people who are having trouble grasping this is that China is approaching a tipping point in its carbon emissions, where they’ll start plummeting rather quickly. They are, as is noted, the largest purchaser, manufacturer and purchaser of electric vehicles in the world, dominating the electric vehicle and battery markets.That’s true for buses, that’s true for trains, that’s true for trucks. They have electrified all that. And because they don’t have natural gas, they only have coal, a lot of their industry is much more heavily electrified than would be expected from the outside. Their industry is already consuming electricity in places where other nations, including Canada, including the United States, including in Europe, are still using fossil fuels for heat provision as a classic example. There’s going to come a point where they have so much electricity and so many things are electrified, where their carbon emissions are going to start going down. As we start seeing these carbon border adjustment mechanisms, China will become quite a bit more competitive.

As one example, China’s grid carbon intensity, its carbon dioxide equivalent per kilowatt hour, is now down to where the United States was in 2012, on average. It’s not that far behind the United States in terms of carbon intensity of its grid and its building renewables a lot faster than anybody else. India’s big competitor in this thesis is China in an export oriented world where carbon border adjustment mechanisms will be. And so India needs to ramp up its game on carbon pricing and a regulated carbon market, not a voluntary one, and also on electrification and renewables.

One of the big discussions in India, as I understand it from the outside, please do share nuances with me in the discussion, is that there’s a strong concern that carbon pricing will inordinately impact the least affluent in Indian society. There’s a significant amount of, especially the rural people who don’t have or concern about the money.

What happens in Canada, as an example, is a progressive tax, progressive carbon price. Everybody pays little bits of stuff. They pay a little bit extra when they buy gas. They pay a little extra if they’re heating their home with natural gas. But every three months, every Canadian who pays taxes receives a dividend from the government, which is their portion, their household’s portion of the carbon price. So the carbon price is returned to people. People who emit more carbon are more affluent. They pay more. The people who emit less carbon because they’re not affluent, receive more as a ratio. The economic assessment is that the average people in the bottom 60% of income actually receive more dividends than they pay in carbon pricing over the course of the year. The example of the oil heating people in eastern Canada was a case where that wasn’t true. And so that was addressed. We found a solution to that. That can work in India and anywhere else as well. What it enables the economy to do is ensure that we don’t leave people behind.

Now, the secondary part, there is, unfortunately, an international perspective to this. China is going to the World Trade Organization with concerns about the EU’s carbon border adjustment mechanism because it is much higher than their carbon price. And while their trajectory is good, that doesn’t mean they’re there yet. The concern there is that poorer nations who are going through the process of increasing their energy consumption are still high emission and they will be impacted by the carbon border adjustment mechanism in an unfair way. That’s a reasonable concern.

Certainly when I was looking at northern African countries related to Europe’s desire for them to manufacture green hydrogen for Europe, my guidance to those northern African countries a couple or three years ago was what you should do is take all the European money, build lots of wind, solar, transmission and storage, and say thank you very much and decarbonize your grid, because a carbon border adjustment mechanism is coming. Northern African countries export a lot of products to Europe and they will be priced for carbon. And so if their economies remain high carbon, they will be impacted negatively on the export side. The EU wanting to invest for their own energy requirements was an opportunity.

Morocco had the best hydrogen strategy, which was, yeah, sure, come here, we’ll take your money, we’ll build lots of wind and solar, we’ll build lots of transmission, we’ll build a lot of hydrogen to decarbonize our economy. If we have any left, we’ll sell it to you. There are opportunities here as we transition around the world.

There’s a piece, there’s one other piece of challenge related to this that I want to talk about, and that is the voluntary carbon markets. The third world is selling a lot of land and forests to the first world, to the developed world, for pittances, one or $2 per ton of carbon. And that’s not pricing it appropriately. It’s going to leave those countries and they can’t double count. So in 20 years, when those countries are trying to finalize their decarbonization journeys, they won’t be able to buy carbon credits. They’ll be paying the full price of $300 US per ton. So they’re effectively selling for $1 today something that’s going to be worth $300 in 20 years and they won’t have that money. And so the voluntary carbon markets are in many cases going to fall apart quite rapidly because they do not align with what’s actually happening. Governments in the developing world will simply say, these are worthless contracts, we will not do this anymore.

That’s the end of my talk. Carbon pricing is a critical component, gets into all sorts of things. It provides economic certainty, it provides competitive advantages to decarbonizing firms and organizations. Let’s have a few questions.

RP: Thank you. Thank you, Michael. Could you elaborate little more on the voluntary markets? Some of our countries are not obligated under any of the existing framework because our per capita emissions are very low. So voluntary market is something that India and many other developing countries are promoting. So how it’s fairing. And also tell us about how carbon tax can be used as a financing tool for decarbonization or energy transition.

MB: So yeah, to the first question, the voluntary markets, about 5% of voluntary carbon credits have been high quality. The voluntary markets are highly subject to bad actors exploiting them, treating them as ways to do cash grabs in the short term by going to poor countries and buying voluntary credits. A voluntary unregulated credit has poor quality control. This is characteristic of the vast majority of them. I haven’t spent enough time looking at India’s voluntary carbon market to assert more than I’m concerned about it as a class, because the class as a whole has had such poor performance and it has clear and significant problems in terms of exploitation of poorer countries, in many cases by rich corporations in the west. And that’s going to turn into a situation where the poor countries need those credits and they’re just going to tear up the contracts.

They are effectively greenwashing in most cases. The social cost of carbon is an interesting question. I will say the following, that Europe and North America have effectively harmonized on a high social cost of carbon. And that’s not the cost of carbon to the west, that’s the cost of carbon to the world. There’s an interesting question as I look around the world, only one Australian state has a social cost of carbonous and it’s very low. I would say though that leading practices, if both Europe, the US Environmental Protection Agency and Canada have harmonized on a social cost of carbon for the world, which is fairly well aligned, that’s probably leading practice in terms of accepting the reality of the cost of every ton of greenhouse gas or equivalent that is emitted per year and should be taken seriously.

That’s three very significant organizations with a lot of ability to do the work. I find that the social costs of carbon which are low are interesting because I wonder what boundaries and constraints they put around deciding what the social cost was. I would say that the Australian state put a boundary around it that was for the state and its citizens, which is a choice as opposed to around the world, because this is a global problem. And so voluntary markets to that point, they are not aligned with the social cost of carbon and they have a mechanism for you opt in or out for your own reasons, typically marketing or a sense of virtue.

For example, the amazing organization Tata, which is a trust that does amazing charitable works with its vast affluence and revenue. Incredible company. I spent some time looking at it a few years ago. I’m sure it’s going to be a participant in this, which is great because it’s a good social good, but depending upon people to do the right thing, depending on organizations, especially to do the right thing in a voluntary way, is a recipe for people exploiting that system. I spent time talking to Doctor Joseph Romm, who’s now working with Michael Mann at the University of Pennsylvania, about this. I would urge people to look up Doctor Joseph Romm’s paper from December on voluntary carbon pricing and carbon markets, because it’s a rather stunning indictment of the failures of them. He and I agreed that a regulated inclusive carbon pricing solution is by far the better choice.

I also assert that the social cost of carbon, if the major economies of the west, who have all said this is the global problem, this is an admission on their part that they created the global problem. If they’re all saying that it’s this big, then we should take that seriously and the rest of the world should be considering what are the boundaries and the harmonization of that. What was your second question, Reji?

RP: I asked about how carbon pricing can be used for financing decarbonization.

MB: Sure it can. In a regulated market where there is price certainty, because that is a clear indicator in a business case that will have value. A voluntary market. I can’t imagine a bank is going to say, well this is voluntary market, it’s not going to be considered as credible or likely to have a value, especially because banks will be looking around the world and lending agencies will be looking around the world to say, well, these price points are not increasing, they’re collapsing. There’s a lot of fraud in the space. We just don’t consider them credible. Whereas for the EU and Canada, there’s a value that is fairly clear. And the price signal is very strong for that.

Even now, though, to be clear, in Canada we have an election coming up which is likely to go against the carbon price. The competitor who’s coming in is a right wing populist and has quite a good chance of winning. He, as right wing populists do, has got a slogan, “axe the tax”, and by that he means the carbon price. It’s a stupid, simplistic slogan, hence the value for populists. But it’s not in aid of carbon pricing. So Canada is at risk, just as Australia was in similar circumstances a decade ago. In Canada, it’s likely that including carbon pricing in a business case, the bank is going to deprecate that value proposition. In a business case, an investor is likely to deprecate that value in a business case, simply because the possibility of that carbon price going away is reasonably high.

To be clear, the government that brought the carbon price in has fought three elections with that as a campaign plank and had it implemented for two elections and it stayed in power. But this is a challenge with carbon pricing in general. It’s hard to explain. It’s easy to attack. And so from a fiscal perspective, that makes it an interesting thing to price.

RP: And value as the global carbon markets are getting integrated. My carbon credit in India, I can trade in Europe or in America. So many of those exchanges which has come up, some of them very reputed ones, in a year ago, there was some major, what you call falsification, double accounting or something, which came, manipulation came and they admitted, finally they were fined in USA, one of the very reputed carbon trading platforms. So I don’t want to name them, I know the name. But these kind of things, how do we, how the entire system globally you think will emerge, where everything will be transparent and no double accounting, no manipulation of certificates. Your thoughts on that?

MB: My thoughts are that voluntary carbon markets are so fundamentally flawed that countries should enact policy for regulated carbon markets with ascending carbon prices and clear policy statements. And as federal national policy, avoid the voluntary markets. If private individuals want to speculate upon voluntary carbon pricing, sure, let them. But as a national policy, I think it’s short sighted.

RP: There is a question from one of the participants. It’s on the screen. You can read it.

MB: Carbon pricing of renewables is an interesting one. I mentioned that China’s economy, China’s industry, is electrifying rapidly. Well, China’s industry is building solar panels, batteries, wind turbines and electric vehicles. With every additional degree of renewables on China’s grid, the carbon intensity of their products diminishes. As we start seeing the green steel I talked about — I urge people to go and listen to the last discussion on industrial decarbonization, where I address steel — we can decarbonize steel, we can and will decarbonize cement and concrete. We can and will decarbonize manufacturing. We can and will decarbonize forestry. And so as we electrify and decarbonize industry and supply chains, the carbon emissions will go down. But we do have to think about the end today from cradle to grave for the carbon emissions of all those cycles.

Wind turbines and utility scale solar are quite low carbon emissions per life cycle, carbon assessment across their lifespan. But that does include pricing the concrete and steel we use in the manufacturing of them as a necessary part of a level playing field. It’s an interesting question. They are highly virtuous in terms of lower carbon, but that’s true for all the electricity they generate for their entire life. Wind turbines have a carbon payback for electricity in roughly four to eight months. Solar panels, two to four years, and so they last for 25 to 30 years. Being very low carbon, there’s a strong merit order, and the carbon price is not onerous upon them.

I did the calculation recently for an organization choosing to build a gas plant in Europe versus a wind farm or solar farm in Europe, using the EU’s budgetary guidance for major projects in Europe. And it has a high price point. Europe is sending a clear policy signal saying that $300 per ton of carbon in 2040 is what you will be paying. Then I did the emissions for the wind farm or solar farm versus the emissions for the natural gas generation, and found that it was almost impossible under those conditions for someone to derive a business case for a natural gas plant. But the wind and solar farms were even with their carbon debt. I put in the lifecycle carbon assessment values for the wind farms and burdened them with the carbon price. They were just vastly more profitable than the natural gas plant.

Batteries are very similar because they’re not consumed, because in operations they do not produce carbon dioxide. They just sit there. They have a high carbon debt for manufacturing today, and that’s lowering. But they’re reused. Now, LFP batteries are 15 year assets on grids, and then they are assets which are then mined to make new LFP batteries. As we start moving into this more circular economy, at least an oval economy, then we end up with a situation where the carbon price really doesn’t hinder decarbonization. But in all cases, any place where you can eliminate fossil fuels from the carbon supply chain, your end product, when we price negative externalities, becomes more competitive. This just means that every step of the process is incented to decarbonize.

Green steel becomes viable. Epoxy cements and geopolymer cements become viable. Cross laminated timber becomes viable and cross laminated timber, as I said in my discussion about cement, is an amazing carbon win because every ton of cross laminated timber displaces 4.8 tons of cement and concrete and embodies a ton of carbon dioxide that it sequesters for an extended period of time. It’s quite a virtuous technology. And so we start to get more virtuous technologies. Yes, we have to price the carbon that’s embodied in wind turbines, solar panels, EV’s and batteries. But it’s not a competitive disadvantage for them as long as we price that for their alternatives.

RP: There was another question by another participant which talked about, don’t you feel that it will be a burden, carbon tax will be a burden on developing nations like India? You have carbon pricing. Yes. It’s a very difficult question to answer. Yes and no. So something which has come to last two, we do five year plans on power india. So in the last two plans, we didn’t provision any new thermal capacity addition, but this year there was a more than 10% increase in the peak power during the summer. So all of a sudden there is an activity going on in fast track to add thermal generation. So the numbers, which I hear is they have already finalized some 36,000 megawatt.

We are done in seven years, by 2032, they will add 36,000 megawatt of thermal coal generation. And the bigger number we hear about is about 92,000 megawatt. So where is this number coming from, where will the coal come from? How this will happen, we don’t know. But this 36,00 fast track addition is being finalized. On the fast track is something which has happened in the last 30 days. So this was nowhere to be found. The last major discussion was about adding 8000 megawatt in renewable rich states, such as Rajasthan, Gujarat, etc. Where we can stabilize the renewable energy because of the inertia problems. So that was to come online by 2029. So from 8000 we are already on to 36,000 and to 92,000. How it’s going to play out and how we will go to Baku with this kind of new plans, we don’t know. It’s an interesting time.

MB: Well, I’ll compare and contrast to China again, because I spent time looking at the coal situation in China. It’s much more nuanced as it will be India than western analysts typically give it credit for. While China had permitted 1100 gigawatts of new coal, it had also mothballed, decommissioned, or canceled 775 gigawatts of coal. Bad coal was being decommissioned because coal has from 1.4 tons per megawatt hour down to 800 kilograms per MWh as a range of emissions. China decommissioned a lot of its old lignite coal and its subcritical boilers. It’s building new supercritical coal with washed coal and higher grades of coal. So that’s kind of statement one.

Statement two, they have got rid of a whole bunch of coal plants that weren’t essential or too close to large population centers.

Statement three, they’re running those coal plants the way the United States runs its gas plants, except better, because two years ago China’s capacity factor for its coal fleet was just over 50%. A year ago it was just under 50%. This year it’s 40%. They’re running their coal plants less and less and less, which is a virtuous process. They’re building more for peak demand. The question for China and India is how do you provide a mechanism which enables thermal generation to make a profit on diminishing numbers of hours of generation per year as you displace more and more of it with renewables? Every country is going through this process.

The United States is replacing all their coal with natural gas with high methane emissions. They’re not displacing fossil fuel generation nearly fast enough with renewables. They’re too slow. Every country is going through this debate. We must keep our citizens from freezing to death in the wintertime, from broiling in their flats in the summertime. We must keep the lights on, must keep industry going. But increasingly, it’s just with collapsing capacity factors of fossil fuels, we start putting in storage, which means that we can move timeshift, as we discussed, in terms of flattening demand curve. We can time shift solar to other demand periods, we can timeshift wind to other demand periods. And that displaces thermal generation as well.

Certainly right now in North America, solar plants with batteries are displacing natural gas peaker plants. And that’s bidding on the highest value portions of the day ahead market to provide energy at sometimes $90 or $140 per megawatt hour, not be $3 or even higher at $900. So we start seeing this shift, but it’s going to be a shift over time. I’m certainly not going to judge India if you build a lot of thermal coal generation, because I know the trend is you’re going to use it a diminishing portion of the year over time. The concern is stranded assets and challenges there where coal operators can’t afford to keep the plants running, but yet they’re necessary for grid stability. It’s an interesting challenge that everybody has to play out over the next 40 years.

RP: If Trump wins or comes back to White House in the USA, how will fossil fuel influence their energy transition programs?. And India deciding to build another 96, 92,000 megawatt of coal plants. I don’t know how things are going to be at the end of 2024.

The next webinar will be on 18 July, same time the 18 July. Look forward to seeing you all.

Have a tip for CleanTechnica? Want to advertise? Want to suggest a guest for our CleanTech Talk podcast? Contact us here.

Latest CleanTechnica.TV Videos

CleanTechnica uses affiliate links. See our policy here.

CleanTechnica’s Comment Policy