Supporting our resource and energy sector with good, common sense policy can provide an incredible foundation for growth, productivity, security, and prosperity for all Canadians.

By Heather Exner-Pirot

No more pipelines? No more anything

When the Trudeau government was first elected in 2015, it promised to introduce a new environmental assessment process. One that would:

- “restore robust oversight and thorough environmental assessments of areas under federal jurisdiction, while also working with provinces and territories to avoid duplication”;

- “ensure that decisions are based on science, facts, and evidence, and serve the public’s interest”; and

- “end the practice of having federal Ministers interfere in the environmental assessment process.”

The Impact Assessment Act has achieved none of those goals.

When initially proposed, Bill C-69: An Act to enact the Impact Assessment Act and the Canadian Energy Regulator Act, to amend the Navigation Protection Act and to make consequential amendments to other Acts (known colloquially as the “no more pipelines” bill) was so unpopular that it sparked protests in the streets of many large western cities. It prompted the Senate to hold hearings in Ottawa, Vancouver, Calgary, Fort McMurray, Alberta, Saskatoon, Winnipeg, St. John’s, Halifax, Saint John, and Quebec City. Provinces, energy associations, and business groups opposed the bill vigorously.[1] Yet it still passed in 2019.

At the time, Grant Sprague and Grant Bishop argued for the CD Howe Institute that “If the federal government wishes to reverse the decline in major investments in energy and mining, the current Bill C-69 is unlikely to be a remedy. By increasing political risk and timelines for project reviews, Ottawa’s proposed cure looks likely to worsen Canada’s present disease.”

Indeed, it did. And with just one project approved under the auspices of the Impact Assessment Act (IAA) five years after it became law (Cedar LNG, approved in 2023), the disease looks to have killed the competitiveness of the Canadian energy and resource sector. A post-mortem is in order.

The rise and fall of global resource and energy investment

The commodity market moves in cycles, and the Canadian energy and resource sector is not immune. The last supercycle (a period marked by strong demand and high prices) began in the early 2000s, and continued until 2014, at which point the boom turned to a bust.

That cycle was largely the result of strong demand driven by Chinese economic ascendance. Incredible GDP growth rates, averaging around 10 percent a year, occurred in China during this period, as that nation reaped the benefits of the demographic dividend from its one child policy: a temporary bulge in the working age population, with relatively few dependents either older or younger.

As the saying goes, the cure for high prices is high prices. Investment poured into the energy and mining sectors, ultimately outpacing demand and leading to a bust. This was further hastened by the shale revolution: the technological innovation of hydraulic fracturing (fracking) and horizontal drilling that unleashed copious new reserves of oil and gas in the United States, flooding oil markets and bringing global energy prices sharply down.

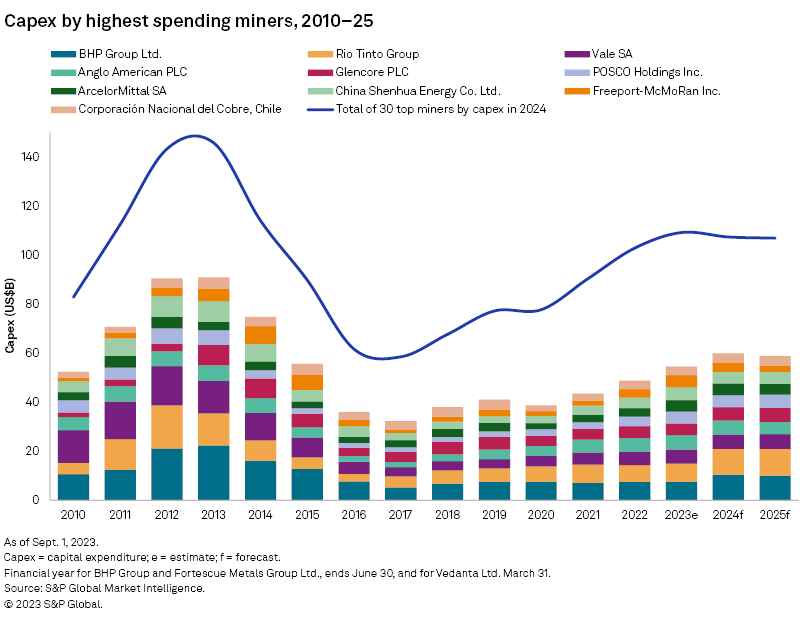

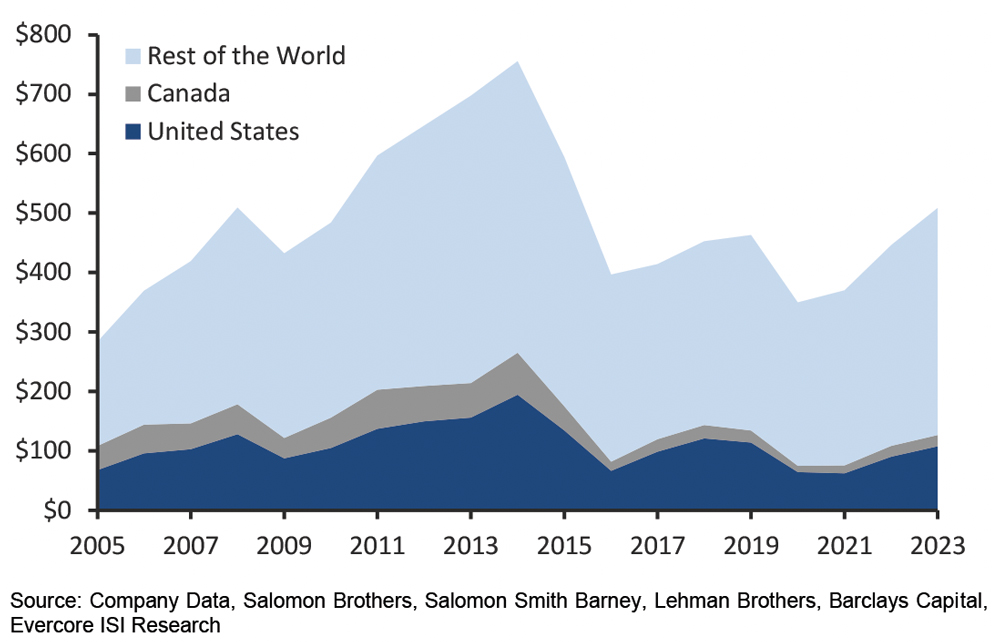

The global economy from 2014–2022 largely benefited from low energy and resource prices (and concomitant low inflation and interest rates) of the cycle’s down phase, in many cases artificially supported by investor losses. But it also led to a decade of much lower investment in commodities. In fact, capital expenditures in the global mining and oil and gas sectors both peaked over a decade ago, in 2013 and 2014 respectively (see Figure 1 and Figure 2).

Figure 1 Global capital expenditures of top 30 miners, 2010–25 Source: S & P Global 2023

Figure 2 Global capital expenditures in oil & gas, 2005–2023, Source: Evercore ISI, 2023

The world has since added a billion people to its population, and hundreds of millions more to the higher-consuming global middle class. The imminent result will be the emergence of a new commodity cycle, where demand will again outpace supply, thus provoking higher prices, inflation, and all the geopolitical and economic pain that goes with it. There are clear signs that we are in the beginning of this cycle already in the first half of 2024, with resilient oil prices, record gold prices, and strong year-to-date performance in copper.

Oh, Canada!: A double whammy

Canada’s resource and energy sector suffered two hits in 2015. One was the global commodity bust. The other was the election of the Trudeau Liberal government, which was intent on transforming the Canadian economy from its rollercoaster dependence on global commodity prices to one built on a more resilient and scalable knowledge economy. As Prime Minister Justin Trudeau articulated to his audience at the World Economic Forum in 2016, “My predecessor wanted you to know Canada for its resources. Well, I want you to know Canadians for our resourcefulness.”

Paired with this thinking has been a series of punishing new policy and regulations that stymied growth and investment in energy and resources. Amongst those on what has become a very long list are: the Impact Assessment Act, the oil tanker moratorium, the moratorium on offshore Arctic oil and gas licensing, industrial carbon pricing, the UNDRIP Action Plan, rejection of the Northern Gateway pipeline, methane regulations, Clean Fuel Regulations, the proposed Clean Electricity Standard, and now the proposed emissions cap and cut of 35 to 38 percent from 2019 levels for the oil and gas sector only – right as the TMX and Coastal Gas Link pipelines are set to come online and are finally providing the ability to expand production to meet demand outside of the shale-soaked United States energy market.

Although Trudeau said in March 2024 that market mechanisms, like a carbon price, are better for lowering greenhouse gas emissions than the “heavy hand of government” through measures like regulations and subsidies, his government has gone all-in on both. And while there is certainly a case to be made around the relative merits of the carbon tax as the most efficient, transparent climate policy, the Canadian oil and gas sector benefits from no such thing. It now faces three layers of carbon pricing: provincial high emitters carbon pricing (e.g. TIER in Alberta), a federal carbon tax, and soon a cap-and-trade system via the emissions cap; hardly a light hand.

The Liberals have found it easier to pass legislation that hampers resource and energy development than those that support it; of the six proposed Investment Tax Credits (carbon capture utilisation and storage, clean hydrogen, clean technology, clean technology manufacturing, clean electricity, and most recently EV supply chain) designed to advance the energy transition and compete with the US Inflation Reduction Act, none have been passed into legislation at time of publication. Canada has become good at implementing policies that deter investment, but not those that attract it.

Business leaders are saying as much. In a 2023 survey of North American energy sector executives by the Fraser Institute, 68 percent of respondents were deterred by the uncertainty concerning environmental regulations in Canada compared to 41 percent in the United States, which performed better in 13 out of 16 policy factors. In a 2024 survey of Canadian mining executives by KPMG, 98 percent said their companies require more investment, government commitment, and favourable tax policies to support their growth in critical minerals development. In a 2024 survey of Canadian transportation executives, 56 percent expressed dissatisfaction with our regulatory framework, deeming it restrictive, slow and suffering from both lack of action and hasty decisions that lead to unintended costs. This year, positive sentiments on Canada’s overall business environment hit its lowest level – 20 percent – since that survey’s inception in 2017.

The numbers are not good

The result of all these policy and regulatory burdens, tied with a weak commodities market, has been predictable: a huge decline in investment in energy and resource projects in Canada since 2015. The impacts go beyond the oil and gas sector, which Ottawa has deliberately sought to reduce. An uncompetitive regulatory and policy environment has hurt investment in electricity, mining, and transportation infrastructure as well, sectors which are foundational to the energy transition the government so badly wants to advance.

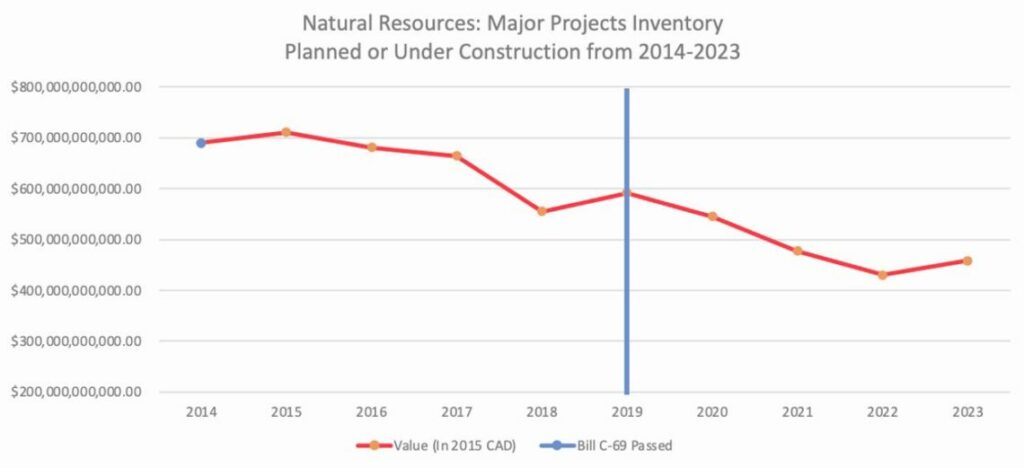

Data from Natural Resources Canada’s annual major projects inventory (those that are under construction or planned within the next ten years) show a decline from $711 billion in major projects at its peak in 2015, to $572 billion in 2023. That’s in real dollars. If Canada had retained 2015 levels of planned investment and kept pace with inflation, the figure today would be $886 billion. And if had also kept pace with population growth – i.e., if the planned investment in major projects had kept pace on a per capita basis – the figure would be $985 billion.

Major project investments in Canada are in a death spiral. And there’s little reason to believe it will turn around soon. Megaprojects TMX and Coastal Gas Link have recently been completed and will be removed from next year’s inventory. LNG Canada and Site C will follow soon after. What megaprojects will take their place?

The declines are occurring across the board. Oil and gas, predictably, has faced the greatest absolute decline in the major projects inventory, dropping from 155 major projects in 2015 worth $456 billion, to 87 projects worth $319 billion in 2023 (equivalent to $259 billion in 2015 dollars): or a 43 percent drop in value. But it’s even worse elsewhere.

Despite the need to electrify significantly more energy use to meet net zero goals, the electricity sector declined from 223 projects worth $156 billion in 2014, to 182 projects worth $98.9 billion in 2023 (equivalent to $78.9 billion in 2014 dollars): a 49 percent drop in value.

And despite the need for far more minerals to provide the raw materials for electricity, renewables, and electric vehicles, as well as the ability to process them domestically, the mining sector fell from 150 projects worth $166 billion in 2014, to 129 projects worth $93.6 billion in 2023 (equivalent to $75.2 billion in 2014 dollars): a 55 percent drop in value.

Clean technology did see growth in this time frame, moving from 172 projects worth $107.5 billion in 2017 (when it became its own category) to 233 projects worth $159 billion in 2023 (equivalent to $137 billion in 2017 dollars): a 27 percent increase in value. But that growth was not in hydro, the value of which declined -42 percent since 2017; nuclear, which declined -28 percent; or wind, which declined -3 percent. In terms of value of new projects, it was overwhelmingly in carbon capture, utilisation, and storage (CCUS), and to a lesser extent solar.

Figure 3 Canada Natural Resources Major Projects Inventory Value 2014–2023 Source: Calculations based on NRCan Major Projects Inventory reports.

These statistics reflect projects that are planned and under construction, but many will never reach a Final Investment Decision (FID). It’s worth noting that the number of projects that were actually completed declined -36.36 percent between 2015 (88 projects) and 2023 (56 projects).

Impacts on production

An inability to attract investment in major projects ultimately leads to plateaus or declines in production.

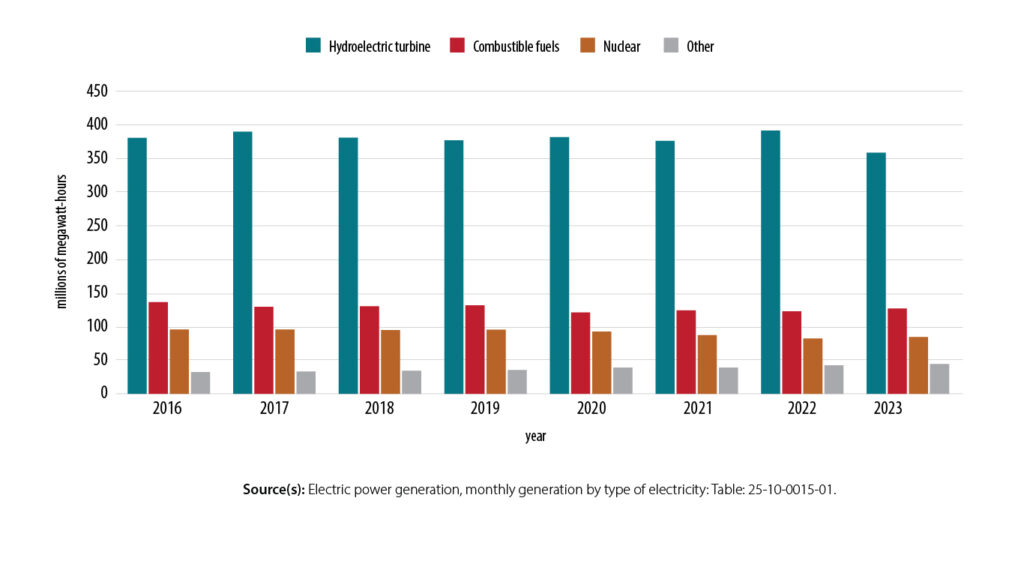

Electricity generation in Canada in 2023 hit its lowest levels since 2016, at 615.3 million MWh, despite the policy imperative to electrify more heating and transportation energy use as a strategy to reduce emissions. The challenge was exacerbated by drought, which greatly impacted hydroelectricity generation.

Figure 4 Electricity generation in Canada by source, 2016 –2023. Source: Statistics Canada Table 25-10-0015-01

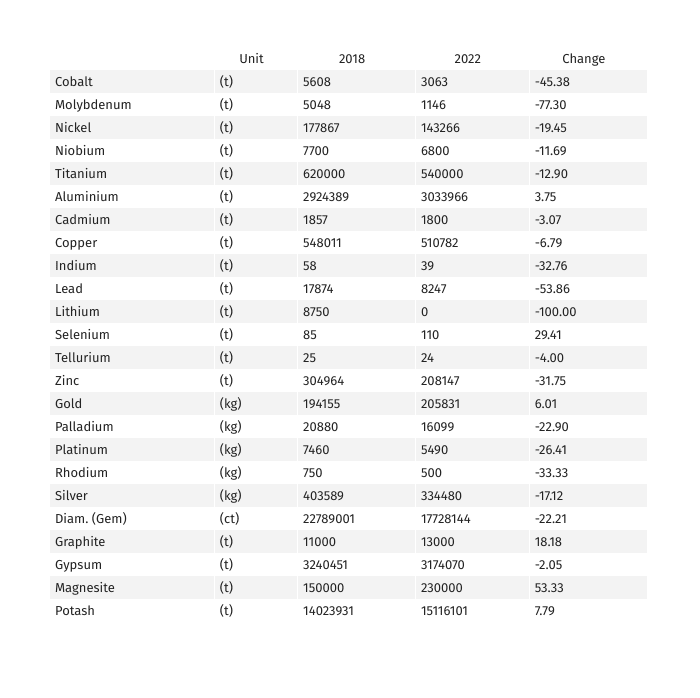

Mining has suffered even greater production losses than electricity, despite the acknowledged need for Canada, as the world’s second-largest country and a key NATO ally, to ramp up critical minerals production in order to reduce Chinese dominance in global mineral production, processing, and clean technology manufacturing.

Far from being a leading mining nation, Canada now ranks just 8th globally in mineral production by volume. Between 2018–2022, Canadian critical minerals production atrophied, with nickel, cobalt, lithium, uranium, zinc, lead and platinum all posting double digit declines (see Table 1).

Table 1 Production of Selected Mineral Raw Materials, Canada, 2018–2022. Source: World Mining Data 2024

Oil and gas, counterintuitively, have seen increases in production, hitting record levels of late. This is largely because of decisions and investments made in the last commodity cycle. Importantly, Enbridge’s Line 3 came online in 2021 and provided significant new oil export capacity to the United States. The coming online of the TMX and CGL pipelines this year, and the completion of LNG Canada next year will allow producers to continue to increase production, and new Canadian oil & gas production records will be set. However, there are no more major pipelines in the pipeline, and egress constraints will again limit new Canadian production around 2027.

Reviving the economy

Canada’s political and economic leaders have become seized of late on the nation’s declining growth and productivity, and the result those are having on Canadian’s well-being and prosperity.

According to research published by the Library of Parliament, from 1980 to 2022 Canada’s productivity decreased from 102 percent to 77 percent of the rate of the United States, and from 108 percent to 93 percent of the average rate of the G7. A recent study by Deloitte showed that per capita GDP declined in five of the past six quarters, falling by 1.7 percent in 2023 and facing a similar decline in 2024. The Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) projects Canada will have the slowest real per-capita GDP growth among advanced economies between 2020–60.

This projection should be taken as warning rather than fate. Canada has all the tools to escape it, not least our incredible endowment of natural resources. We are blessed with world class reserves of oil, natural gas, and uranium, and possess economic deposits of practically all critical minerals. These can further support world class sectors in EV manufacturing, nuclear development, low carbon fuels and petrochemicals. We are likely entering a protracted commodities bull market. The only thing standing in the way of reaping its rewards is ourselves.

Post Script on a Post Mortem

Concern has been expressed in recent years about Canada’s dependence on natural resources. A lot of “propaganda” has been circulating, which tells us that these are yesterday’s industries; that the only future for Canada is in the knowledge-based industries; that our resource industries will go, and should go, the way of the dinosaurs.

[We have] spent the past year and a half looking behind these perceptions and attitudes. We have found that the resources industries of Canada are still our strongest asset in the international marketplace and are key to our country’s capacity for wealth generation. However, unless we take action to reinforce these vital industries, we may lose the advantages they bring to our economy…

The industry recognizes that environmental regulation is necessary and desirable, but much more needs to be done to make regulations and their application more efficient. In [our] view, unwarranted delays and inconsistencies caused by jurisdictional confusion must be eliminated.

These words could be mine, or any number of Canadian economic commentators from the past five years. In fact, they come from a 1993 committee struck by then Prime Minister Brian Mulroney, on “Competitiveness of the Resource Industries.” La plus ça change.

The embarrassment in some circles around Canada’s “hewers of wood, drawers of water” status seems chronic. But it is misplaced. The quality of our resource and energy sectors is world class. And they are not founded on mere rent-seeking: the level of Canadian business performance in the energy, mining, agriculture, and forestry sectors, including on environmental, safety and social metrics, takes incredible engineering and finance expertise, requires highly skilled labour, and leverages technological and scientific innovations.

Bright spots in the natural resource sector’s performance have mostly been despite, rather than because of, federal government policy. As we move into a prolonged bull market for commodities, the entreaties of the last century should be heeded. Let us celebrate and support our resource and energy sector with good, common sense policy. When we do, it can provide an incredible foundation for growth, productivity, security, and prosperity for all Canadians.

Heather Exner-Pirot is a senior fellow and Director of the Natural Resources, Energy and Environment program at the Macdonald-Laurier Institute and a Special Adviser to the Business Council of Canada. She is a Global Fellow at the Wilson Center in Washington DC, the Research Advisor for the Indigenous Resource Network and the Managing Editor of the Arctic Yearbook. Exner-Pirot is also a Coordinator at the North American and Arctic Defense and Security Network and sits on the Boards of the Saskatchewan Indigenous Economic Development Network and Canadian Rural Revitalization Foundation. Dr. Exner-Pirot obtained a PhD in Political Science from the University of Calgary in 2011.

[1] The Mining Association of Canada, by contrast, supported it on the grounds that it was an improvement to its forebear, the Canadian Environmental Assessment Act (CEEA 2012).

Share This: