The National Highway Traffic Safety Administration (NHTSA) recently proposed new fuel economy standards that, together with the Environmental Protection Agency’s (EPA’s) greenhouse gas emissions standards, are meant to continue to reduce fuel use from new passenger vehicles. The fuel economy program, known as CAFE (Corporate Average Fuel Economy) because it considers the “average” fuel economy of a manufacturer’s new vehicle fleet, has resulted in over $5 trillion in fuel savings over its nearly 50-year history. However, it does have one shortcoming that has gotten some press recently: automakers can buy their way out of compliance with the regulations, choosing to simply pay a fine in lieu of improving their vehicle fleet.

While for decades only luxury manufacturers had opted to pay fines instead of complying with CAFE, recently General Motors and Stellantis (formerly Fiat-Chrysler) have incorporated the payment of fines directly into their business model, opting to pay fines rather than make the required improvements in efficiency. And now the trade association representing those companies is trying to use the possibility of fines as a rationale for weakening the newly proposed CAFE standards.

Below I walk through why GM and Stellantis have been paying fines and why the bluster over such fines in the future is complete and utter hogwash.

Weak penalties make for weak protections

One reason manufacturers even have a choice under the CAFE program is because the penalty itself is relatively toothless. EPA’s program has severe penalties for non-compliance: not only are manufacturers explicitly prohibited from paying fines in lieu of complying with the Clean Air Act, but the agency can issue a stop-sale order for non-compliance. Moreover, fines issued for non-compliance under the EPA program can be up to $37,500 per vehicle.

In contrast, the fines under the CAFE program had remained virtually fixed since 1975 at $50 per mile-per-gallon shortfall per vehicle, increasing once in the 1990s to $55, and now bookmarked to inflation thanks to Congress, for which the current fine is $160. Automakers first pressed then-President Trump to undo the update, and later fought the increase in penalties in court. While they did eventually lose the case, automakers successfully delayed the fine increase to the 2019 model year. But even that larger fine amounts to roughly $1,000 per vehicle in violation, and it’s clear that at least some in the industry are more willing to pay lawyers to try to reduce the fines for non-compliance than actually make the improvements needed to comply and avoid those penalties in the first place.

GM and Stellantis choose size over efficiency

In a business with operating margins in the single digits, it may seem like even $1,000 or so per vehicle could be enough to push manufacturers to comply with the regulations. For two major automakers, history has not borne that out, however, though the rationale for such a decision is a bit different.

For Stellantis, its decision to pay fines comes out of its abandonment of the passenger car market. Rather than continue to sell midsize sedans, which generally have a lower profit margin, Stellantis decided to abandon the segment entirely. This means that its domestically manufactured passenger car fleet, for which there is a separate CAFE standard, will be comprised of crossover vehicles and performance cars, which offer higher margins but worse efficiency. This obviously reduces choice for consumers, but it makes for a sensible business case, and the company made the decision with eyes wide open on the resultant penalties. Interestingly, the company has claimed that this “reflects past performance … and is not indicative” of Stellantis’s future strategy, but thus far there has been no evident shift in behavior.

For GM, the decision was similarly focused on light truck margins, but it’s less easily explained. The average gasoline-powered light truck uses 15 percent less fuel than it did a decade ago—but for GM, that improvement is just 10 percent, with only Volkswagen and Stellantis showing less improvement. And yet at the same time, GM has outpaced industry at selling more light trucks—while in that same time period light trucks have moved from 35 percent to 62 percent of sales, for GM that was a shift of 38 percent to 75 percent. GM has been falling behind industry efficiency gains in exactly the vehicles on which it has focused its marketshare.

And yet, like with Stellantis, this is a choice made by the company—during the last redesign of its full-size pick-up, for example, fuel economy of the base model actually became worse because the truck got so much bigger, and a later engine upgrade merely led to a 1 mpg improvement over the previous generation. Similarly, when it redesigned its full-size SUV, there was no fuel economy boost whatsoever, in large part because the powertrain options were virtually unchanged (in fact, the engine platform dates back a decade). But, with transaction prices for its full-size pickups averaging over $60,000 and its full-size SUVs over $70,000, GM figures it can ask its customers to cover the extra fines incurred by choosing not to do anything to improve the efficiency of those vehicles. This stands in contrast to competitors like Ford and Toyota, which have not only added hybrid powertrains to their full-size pickups but whose non-hybrid offerings also surpass the fuel economy of GM’s trucks.

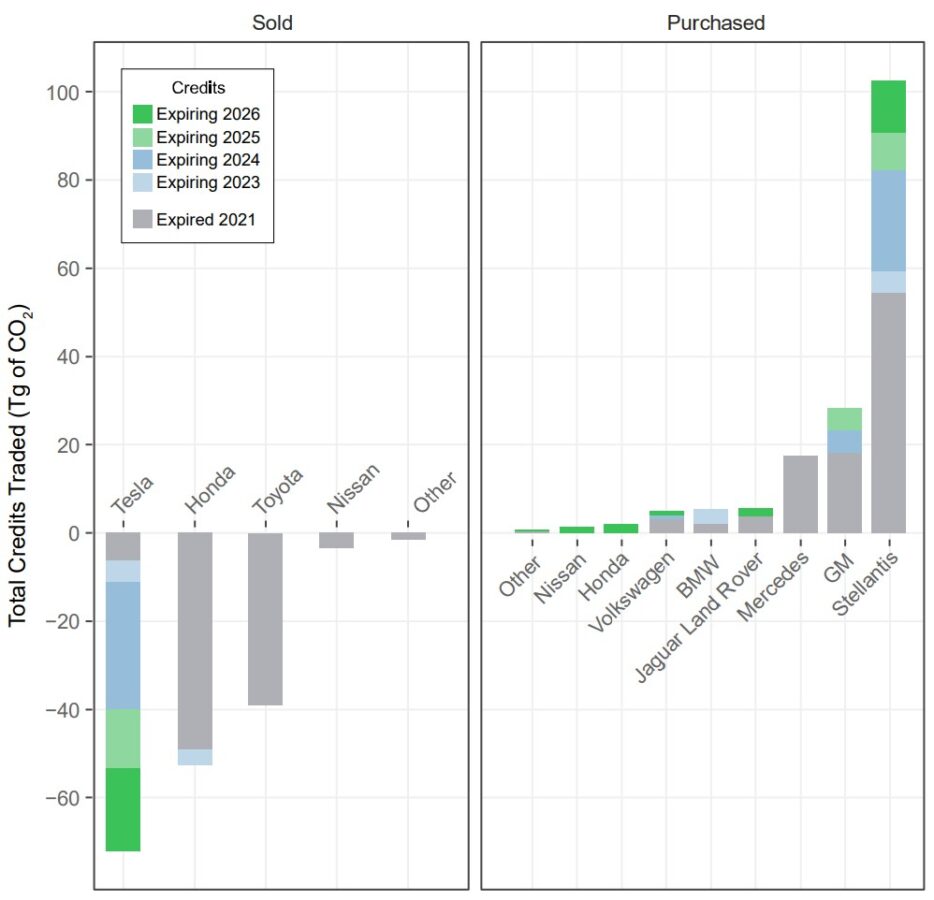

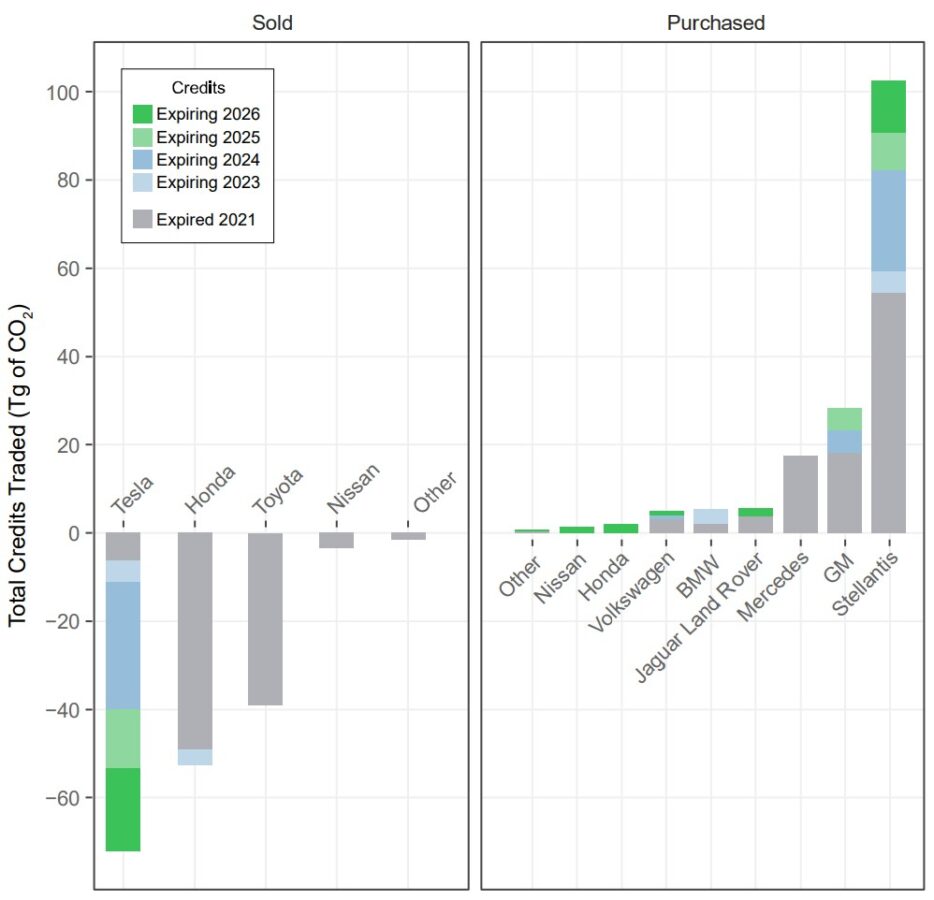

And these business decisions don’t just affect compliance with the CAFE program—they affect compliance with EPA’s greenhouse gas program as well. Currently, for GM and Stellantis, they’ve gotten away with disinvesting in efficiency improvements under EPA’s program because they can obtain credits from manufacturers like Honda and Tesla that are well-exceeding the standards (see graph below). But can this really be a viable long-term strategy? And can other manufacturers make the same decision, harming consumers in an effort to bolster their bottom lines?

This strategy is not sustainable

Manufacturers like GM and Stellantis want you to believe that these decisions are out of their hands. They want you to ignore all of the technology options that their peers are putting out there, all of the off-the-shelf technology that could be put to work to reduce fuel for their customers. They want you to forget that these fines are entirely a business strategy.

But is this strategy something that can continue in the long run? The further that a company falls behind, the greater the fines are going to be for non-compliance. And while it may be sufficient to buy your way to compliance within the CAFE program, this has only been possible for GM and Stellantis because they could also buy their way to compliance under the EPA program, thanks to a large availability of credits from manufacturers that are delivering on emissions gains. But as the EPA and CAFE regulations continue to ramp up, those credits will be at a premium, and paying your competitors instead of investing in your own products has to be seen as a short-term strategy…or at least a short-sighted one.

How automakers are trying to manufacture concern

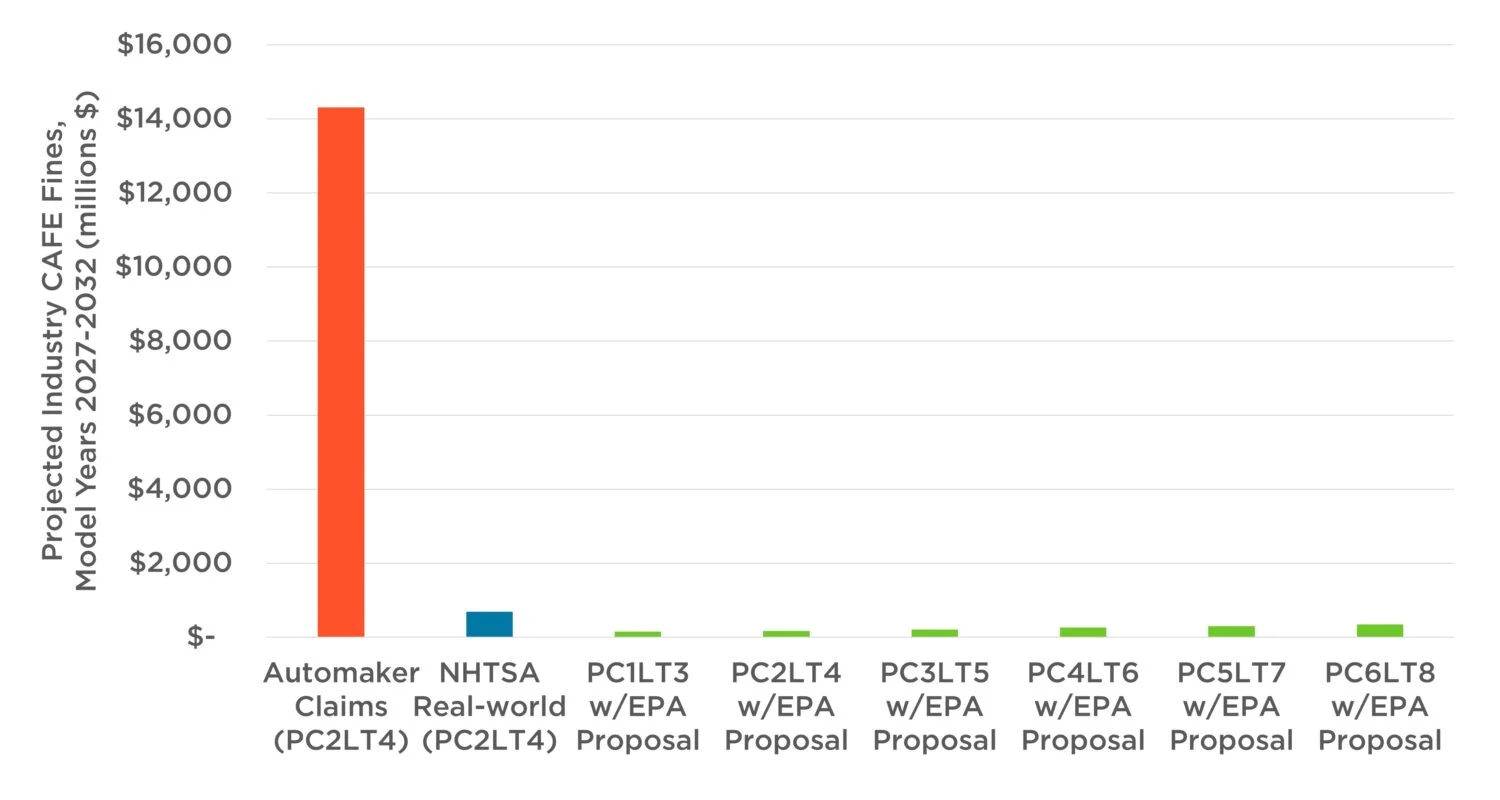

The manufacturers’ trade group cites analysis that automakers will face $14 billion in penalties for future CAFE regulations, claiming that this is a statement about the feasibility of the standards. Obviously manufacturers’ payment of fines today is not related to feasibility but choice, but regardless, is this a reasonable assessment?

The simple answer to this is simply no, it doesn’t make sense. The analysis automakers are relying upon to make this false claim ignores two very important factors: 1) EPA is also setting standards in this time period, which manufacturers as a group cannot simply buy their way out of; and 2) the modeling cited prevents increasing sales of electric vehicles as a way for manufacturers to comply. This latter point is a particularly egregious oversight, since the manufacturers themselves all stood up with President Biden to support his goal of ensuring at least half of all new vehicles sold in 2030 are electric. And in fact, when looking at NHTSA’s “real-world” modeling, manufacturers were anticipated to pay only $691 million in fines.

UCS of course ran our own analysis of the future using NHTSA’s own model, this time also considering simultaneous compliance with EPA’s proposed rules and adjusting the model to account for some flaws in NHTSA’s assumptions on technology and technology adoption. With these corrections, the picture is even more sanguine and sensible. As I noted previously, there are some differences in the statutory authority of EPA and NHTSA that manufacturers complying with EPA’s regulations might not necessarily comply with NHTSA’s regulations, but that is a feature, not a bug, to ensure that we drive efficiency improvements to the gasoline-powered fleet during the ongoing transition to EVs.

But, it’s possible manufacturers ignore complying with the CAFE program in the future through technology gains, as GM and Stellantis have done to-date, choosing instead to pay fines to avoid any additional requirements imposed by NHTSA’s program over the minimum requirements of EPA’s rules. However, these EPA rules set a significant lower limit on how much manufacturers already must improve their vehicle fleet, greatly limiting flexibility around non-compliance with CAFE. On its own, compliance with EPA’s proposed rule generally yields industry-wide average improvements that exceed any standards considered by NHTSA. And finalizing the more stringent alternative UCS and other organizations believe is clearly achievable would even further exceed NHTSA’s standards, on average.

In other words, if automakers comply with EPA’s standards, any fines they could face from NHTSA would be minimal and could be avoided with modest improvements to their vehicles that could save consumers billions of dollars.

According to our analysis, rather than $14 billion in penalties paid, as claimed, even if every manufacturer chose to comply only with EPA’s proposed regulations, the entire industry would pay just over $200 million for not complying with NHTSA’s proposed rule. In fact, if NHTSA finalized its strongest alternative, that would yield just $370 million in voluntary fines if manufacturers tried to buy their way out of CAFE compliance.

If instead manufacturers complied with both NHTSA and EPA’s proposed rules by applying the necessary technology, rather than paying CAFE fines that benefit nothing but profit margins, consumers would spend $3.7 billion less on gasoline.

Now is not the time to let laggards determine the fate of the industry

As the Administration looks to finalize its CAFE rules, it needs to stand firm on its commitment to “abandon the ‘least capable manufacturer’ approach” in assessing economic practicability of its regulations. Fines paid by manufacturers are a choice, and the best way from discouraging that choice at this time is to simply set the most stringent standards possible.

NHTSA must consider what is technically achievable in the context of maximally reducing energy use. NHTSA cannot let automaker decisions that undermine national security and harm consumers’ pocketbooks outweigh its responsibility to set the “maximum feasible” fuel economy standards required by Congress.

Courtesy of Union of Concerned Scientists, The Equation. By Dave Cooke, Senior Vehicles Analyst.