It has long been a trusted mining partner of countries across the world, but there is urgency for Australia to expand its downstream options as the world decarbonises.

Any new industry can present a race to the top, with early adopters best placed to capitalise on new market share and gain a competitive advantage.

This is the case in the context of decarbonisation, where more and more countries are recognising the commercial opportunities that come with establishing the net-zero power sources of a cleaner future.

The situation represents a once-in-a-generation opportunity, and Australia is beginning to understand the role it can play in supporting the green transformation.

Having established itself as a mining superpower, Australia is already a key supplier of the materials driving the world’s renewable energy technologies. But the country can be more than the world’s green-energy quarry, with opportunities to look further downstream and establish vertically integrated renewable industries onshore.

One avenue could be to develop a local battery supply chain, something the Future Battery Industries Cooperative Research Centre (FBICRC) sees as a particularly urgent commercial pathway.

“The clean-energy transition is moving faster,” FBICRC chief executive officer Shannon O’Rourke told Australian Mining. “Government spending on clean energy has increased 30 per cent in the past two years.

“Greater subsidies are driving electric vehicle (EV) demand and increasing commodity prices and volumes. In the past 18 months, the opportunity for Australia has doubled.”

FBICRC released a report in March suggesting Australia’s battery opportunity could contribute $16.9 billion to the Australian economy by 2030.

The report, Charging Ahead – Australia’s Battery Powered Future, highlights Australia’s mining and geological upside, particularly in the production and endowment of critical minerals, and how this can support capabilities further downstream.

This not only encompasses battery manufacturing but other segments in the value chain, such as refining and active materials.

“Australia is cost-competitive across the entire value chain,” O’Rourke said. “We are eight per cent cheaper than Indonesia to produce advanced materials and five per cent cheaper than the United States to produce cells.”

Australia also has a significant advantage in refining, with the potential to be the world’s cheapest producer of lithium hydroxide monohydrate (LHM) through upstream integration in the supply chain. This is the result of Australia’s abundant lithium reserves and mining capacity, which creates natural synergies with downstream applications.

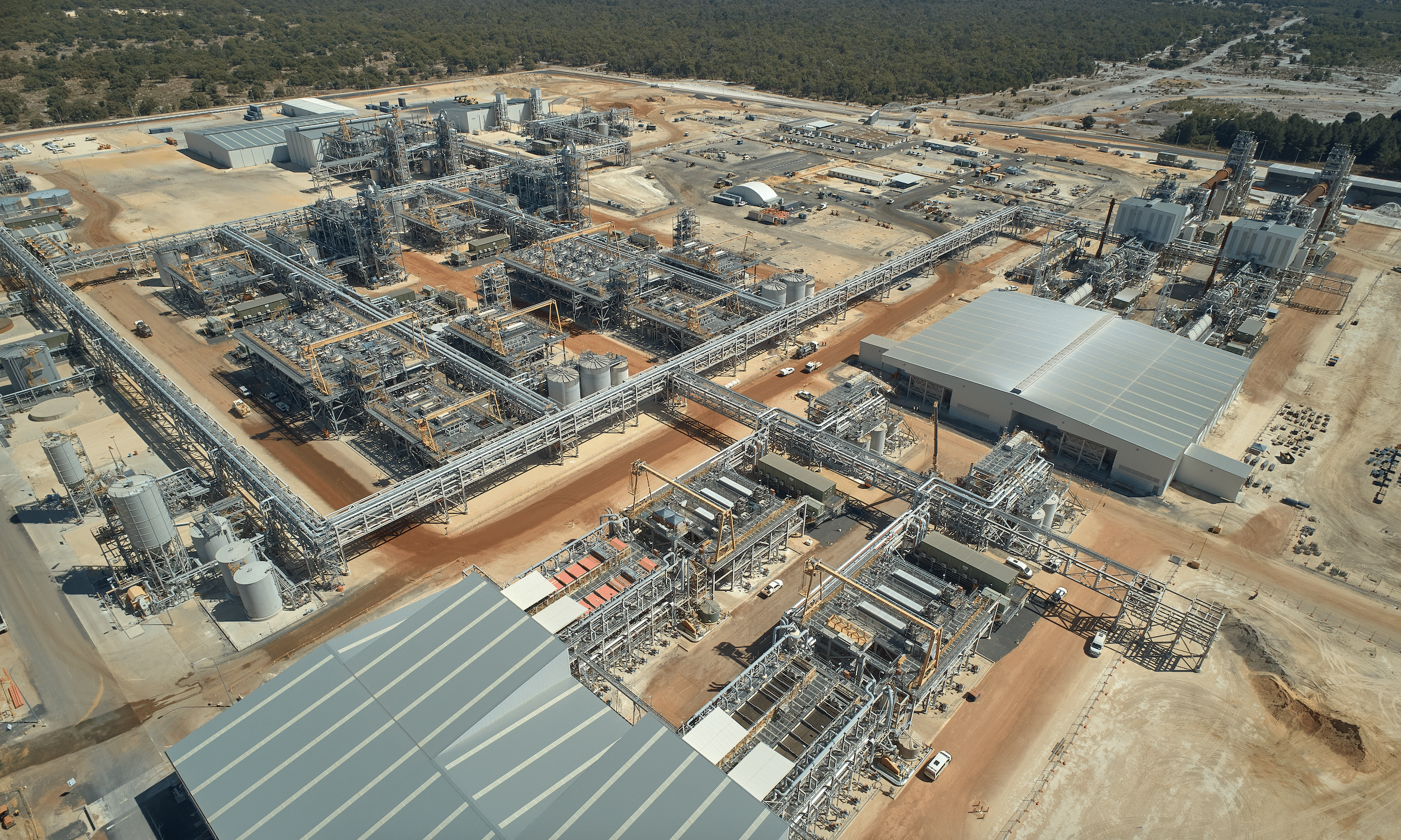

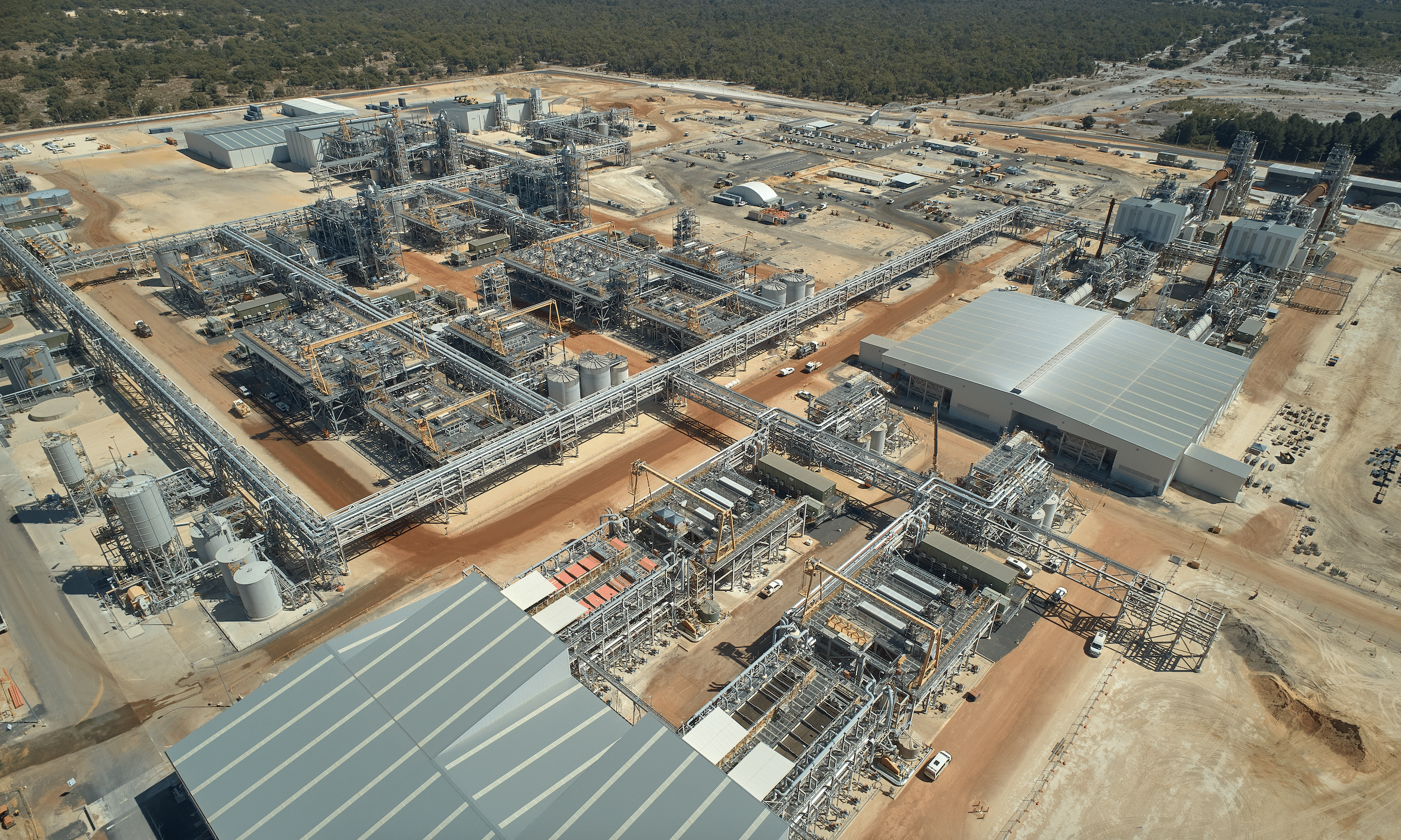

Some Australian companies are already harnessing onshore lithium hydroxide opportunities, with Mineral Resources (MinRes) and IGO producing the refined product from their downstream processing facilities in Kemerton and Kwinana, respectively.

The Kemerton plant sources spodumene concentrate – a raw lithium material – from the Greenbushes lithium mine in WA, which is part owned by MinRes’ Kemerton partner, Albemarle Corporation.

IGO’s Kwinana plant, which it owns in partnership with Tianqi Lithium Corporation, also sources spodumene from Greenbushes.

The lithium hydroxide produced from Kemerton and Kwinana is then shipped offshore for further processing before it is upgraded to active materials such as lithium-iron-phosphate (LFP) or nickel-cobalt-manganese (NCM) – two key cathode inputs for renewable batteries.

But demand for Australia’s upstream products is not solely coming from overseas, with a growing local renewable energy sector seeking more materials than ever.

“Australia’s local demand is skyrocketing,” O’Rourke said. “Bloomberg reports that Australia has the largest pipeline of energy storage projects behind China, and a recent Sunwiz report shows that Australia’s behind-the-meter battery storage market is up 55 per cent year on year.”

The Australian Government is funding eight large-scale batteries to be built across the country, storing renewable energy and reducing the reliance on fossil-fuel power generation. Project locations extend from Victoria’s Surf Coast all the way up to Queensland’s tropical north.

Building independent capabilities is important, but for Australia to effectively harness its battery opportunity, it needs to tackle the matter holistically.

“Building an ecosystem is like trying to solve the chicken-and-egg problem,” O’Rourke said. “A healthy ecosystem needs multiple suppliers, customers and producers, supported by service companies, a flexible workforce, the research sector and government.

“Building that incrementally could take decades, and no other country is taking that approach. Industrial growth is non-linear and needs to be supported by trade and accelerated by domestic support.

“Australia is in a good position. It has multiple projects either announced or operating across all elements of the value chain including refining, materials, (and) cell and system manufacturing.

“We have a complete value chain today, including cell manufacturers. The challenge is building out more capacity and scaling up.”

FBICRC believes Australia can be competitive all the way from refining to manufacturing, but the country must find its sweet spot.

“We do not need to match China’s scale; rather we need to achieve minimum economic scale,” O’Rourke said. “Our minerals strength, our secure supply and our ESG (environmental, social and governance) credentials help sharpen our competitive edge.

“Australia has two cell manufacturing projects which meet this minimum scale: Recharge Industries’ 30-gigawatt-hour-per-annum project in Avalon (Victoria) and Energy Renaissance 5.3-gigawatt-hour-per-annum project in Tomago (New South Wales).

“The NRF (National Reconstruction Fund) and other support mechanisms can help Australia’s lighthouse projects get to scale and develop their supporting industries to build a competitive ecosystem.”

The Australian Government introduced the NRF in October 2022, contributing $15 billion to transform several future-facing industries, including renewable energy and downstream opportunities within the resources sector.

Federal support has also been flowing via the Critical Minerals Development Program, which recently provided close to $50 million in grants for emerging upstream and downstream projects.

This included $6.5 million of funding for Australian Strategic Materials’ Dubbo rare earths project in NSW, $4.7 million for International Graphite’s ‘mine-to-market’ graphite strategy in WA, and $4.6 million for IGO’s integrated precursor cathode active material (pCAM) facility in WA.

IGO is developing its downstream project in partnership with Andrew Forrest-backed Wyloo Metals, demonstrating the power of collaboration in Australia’s downstream ventures.

Collaboration is also a key part of FBICRC’s work and underpins its own pilot plant, is exploring the local production of NCM cathode materials.

“There is a strong collaborative spirit supporting our cathode precursor production pilot plant facility, where we are currently manufacturing high performance materials to world standard,” O’Rourke said.

“Four universities and 18 other businesses have come together to build and demonstrate an Australian manufacturing capability.”

Key mining industry players such as BHP, Allkem, IGO, Cobalt Blue, Lycopodium and BASF have come together with FBICRC to further Australia’s understanding of the active materials industry.

Australia’s battery opportunity is there for all to see, and there are enough developments to suggest that an integrated supply chain could be established.

But for it to happen, Australia must be firing on all cylinders, with stakeholders right across the battery supply chain working together to make this dream a reality.

This feature also appears in the July issue of Australian Mining.