Sign up for daily news updates from CleanTechnica on email. Or follow us on Google News!

The other day I recorded the annual predictions wrap-up with Laurent Segalen and Gerard Reid of Redefining Energy. I’d joined the fun last year for the first time after starting up the Redefining Energy—Tech sub-channel, judging their predictions from the previous year and adding predictions of my own. One of my predictions for 2025 was that there was going to be a bloodbath in hydrogen for transportation.

It’s not going to help that it’s illegal to call hydrogen trucks, ferries, or rail zero emissions or even low-emissions in North America, Europe, or Australia, with both Canada and the EU allowing non-governmental organizations to bring charges. After all, hydrogen in transportation is actually quite high emissions. In the best possible case, it’s many multiples of battery or grid-tied electric, and in average cases close to diesel. In some cases, it’s worse than diesel.

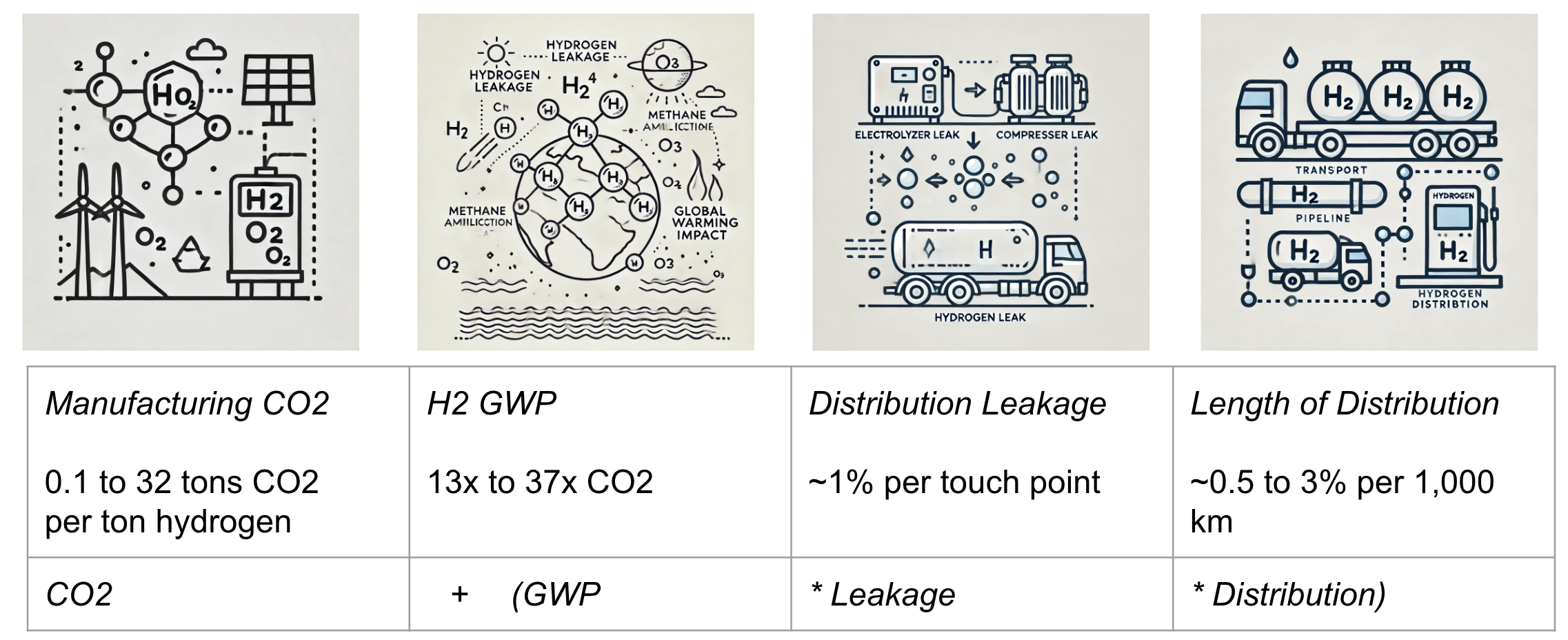

Why? Well, manufacturing hydrogen, in the best possible scenario, requires about three times as much green electricity as just using the electricity in vehicles through batteries, so whatever emissions are related to the electricity are tripled. Also, hydrogen is a greenhouse gas, albeit indirectly by preventing the methane in natural gas or burped out of cows from degrading, with 13 to 37 times the potency of carbon dioxide. And as the smallest or second smallest molecule — depending on whether you ask chemists or physicists — and at the pressures required to have enough of it in one place to do anything useful, it leaks. Every time it moves from container to container or piece of equipment to piece of equipment, a bit leaks. When it’s liquified for long-distance trucking, for example, it turns back into a gas on the road and gets vented.

The combination means that for hydrogen-powered vehicles, an average of 10% of the hydrogen is likely to be vented from manufacturing to getting into the fuel cell.

This isn’t new news, by the way. In 1976, Paul Crutzen (a Nobel Prize-winning atmospheric chemist) and Dieter Ehhalt were among the first to propose that hydrogen could indirectly impact the atmosphere by interacting with the hydroxyl radical (OH). OH is crucial in regulating methane’s lifetime in the atmosphere. Hydrogen competes with methane for OH, extending methane’s atmospheric lifespan, thereby increasing its greenhouse effect. In a pivotal 2001 study, Richard Derwent and colleagues quantified how hydrogen leakage could indirectly increase methane levels by reducing OH concentrations. The 2023 multi-author Sand et al study published in Nature only clarified how bad the problem was, not that there was a problem.

Industrial use of hydrogen in the 20th century saw numerous explosions linked to leaks, particularly in the emerging oil refining and chemical processing sectors of the 1910s and 1920s. Various industrial accidents led to safety regulations about detection, ventilation, and the like. That hydrogen leaks is incredibly well known. It’s minimized as much as possible in industry because it’s expensive, but it’s mostly been a matter of trying to prevent people from dying or being injured, so accurate estimates of leakage rates have been few and far between.

But now the data is coming in. A hydrogen refueling station in California was seeing 35% leakage rates and it took years of remediation and fixes to bring it down to 2% to 10% leakage, just at the site. A hydrogen electrolysis and refueling plant in Europe was seeing over 2% to 4% leakage. A US DOE report on hydrogen boil-off made it clear that even very high-volume refueling stations refilled with liquid hydrogen would see 2% losses just from that part of the value chain.

Basically, you have to make hydrogen in industrial-scale electrolysis plants that are closely monitored and maintained by trained chemical processing engineering professionals and use the hydrogen at the same location and immediately as a feedstock in the manufacturing of something that doesn’t leak to have low leakage rates of the stuff. Make it in a small electrolysis facility at a bus garage or dockside for ferries and the small plant will leak like a sieve. Truck it anywhere and leakage occurs. Moving it from an electrolyzer to a pressurized tank will see leakage. Liquifying it will see leakage. Pumping it into a truck, ferry, or rail car will see leakage.

The best scenario I assessed was a plan to put an electrolyzer beside a bus garage in Winnipeg, which has exceptionally low carbon intensity electricity, about 1.3 grams per kWh, about as good as it’s possible to get. In that scenario, between manufacturing and leakage, I estimated that a hydrogen fuel cell bus would have 15 to 16 times the carbon emissions per kilometer as just using the electricity in a battery electric bus. And Winnipeg found that was too expensive, and pivoted to a methanol reformer as the plan, asserting falsely that it was low emissions too. In actual fact, as methanol has high carbon emissions in manufacturing, a bus filled with hydrogen made from methanol would have 3.2 times the emissions of a diesel bus.

Naturally, the hydrogen-for-energy crowd have not been remotely transparent about this problem. Like the extreme inefficiency of hydrogen-for-energy pathways, the reality that green hydrogen will always be expensive, and the unreliability of fuel cells, most of them are in denial. The ones that aren’t in denial are the ones intentionally delaying decarbonization who don’t care.

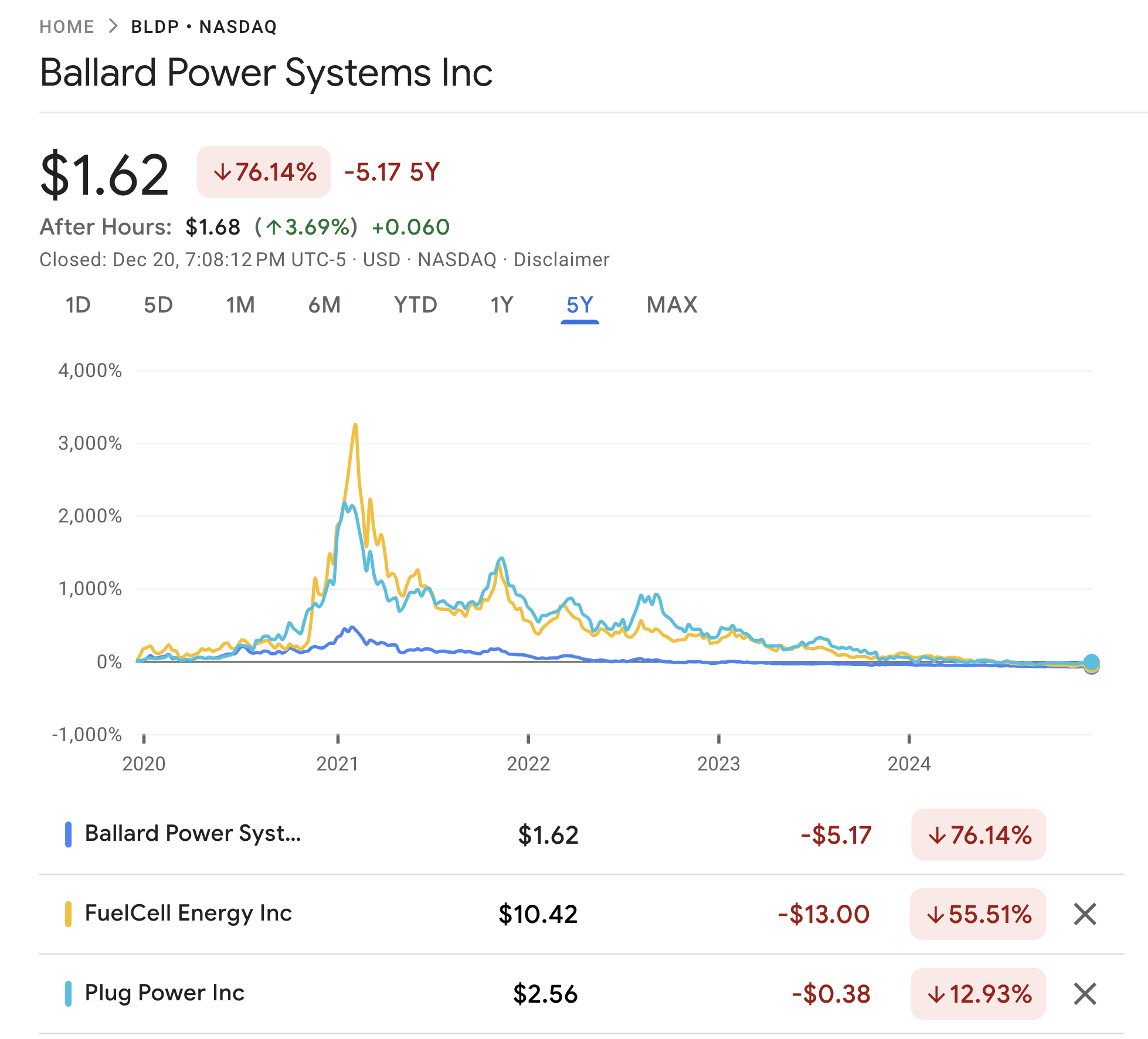

These realities are catching up to companies that have been trying to make hydrogen vehicles, hence my prediction for next year. I’m pretty sure that at least one of Plug Power, FuelCell Energy, or Ballard will finally disappear, possibly all three. They are trading for pennies on the dollar compared to the 2021 miniblip, never mind the early 2000 maxiblip. Ballard Power has never made a profit, losing an average of $55 million annually since 2000, $1.3 billion in total. Even the hydrogen faithful eventually will cut their losses, eat the capital gains loss for tax breaks, and invest in something useful.

I expect that at least one of the major truck and bus firms that’s trying to do both battery electric and hydrogen will follow Quantron into bankruptcy, probably Van Hool or New Flyer. As I noted, hydrogen is appealing because of higher unit prices per vehicle, but every hydrogen truck or bus a firm sells likely costs it 3–5 unit sales of battery electric vehicles because of additional corporate overhead, failure to improve battery electric vehicles to be competitive, and deeply unhappy customers. It’s a recipe for market share loss, not gain.

At least one major western bus manufacturer will abandon hydrogen fuel cell buses, maybe Solaris. Norway will finally stop trying to build hydrogen ferries and replace the single operational hydrogen ferry — 2x the emissions of a diesel ferry, 40x the emissions of a battery electric ferry on the same route, 10x the energy cost of a battery electric ferry — with battery electric.

But Christmas came early for this prediction. Exit Hyzon from the scene. It was founded in 2020 as a spin-off of Horizon Fuel Cell Technologies, focusing on heavy-duty commercial applications such as trucks and buses. Headquartered in Rochester, New York, the company developed proprietary fuel cell systems targeting higher power density and faster refueling times. With operations spanning Europe, Asia, and Australia, Hyzon collaborated with local partners in a vain attempt to build hydrogen ecosystems, including refueling infrastructure, to support FCEV adoption. Despite all the problems listed above and the failures to establish hydrogen ecosystems, Hyzon forged ahead, signing agreements for fleet deployments and participating in pilot projects worldwide. I’d have included Horizon on the stock chart above, by the way, but it’s privately held not publicly traded, so it’s only losing money for its private investors, like mining giant Anglo American.

Now all of those contracts and agreements are worth the paper that they are printed on, nothing.

Hyzon filed for Chapter 11 bankruptcy protection on December 20th of 2024. The filing follows a prolonged period of financial instability, operational challenges, and restructuring efforts aimed at stabilizing the company. Hyzon’s decision to file for bankruptcy reflected its inability to secure sufficient financing or implement effective strategic alternatives, despite earlier efforts to downsize its operations in markets like the Netherlands and Australia. The company had also been dealing with reputational damage stemming from a settlement with the SEC in 2023 over allegations of misleading investors.

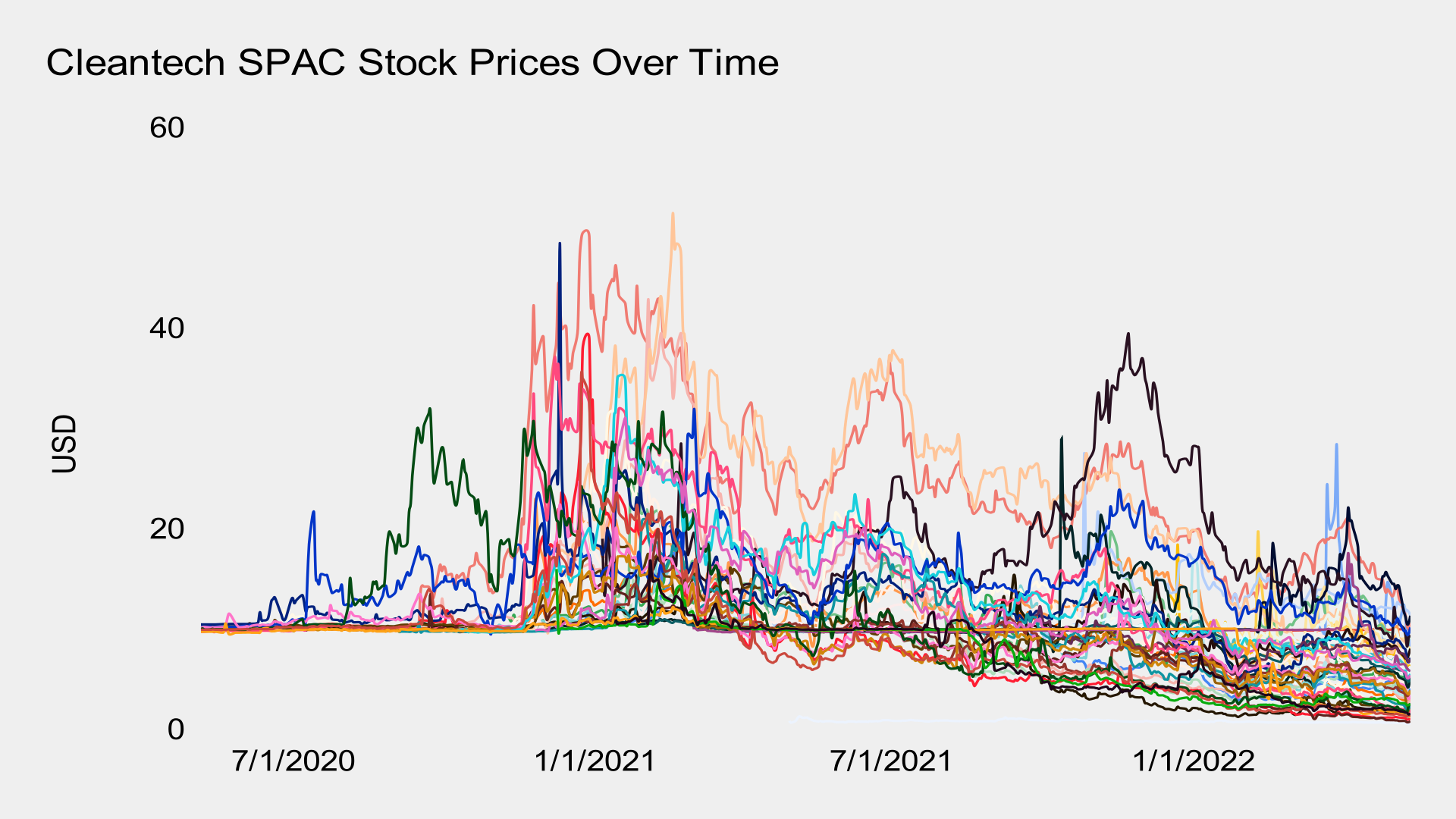

What was that last part? Oh, of course, Hyzon was a special purpose acquisition company (SPAC), and like most of those Wall Street bro enriching vehicles, was a scam to dupe money out of retail investors. Hyzon was on my 2022 list of cleantech SPACs that were going to end badly. The chart above is of 56 cleantech SPAC firms whose stocks had been pumped then dumped by the Wall Street bros. About 60% of them had SEC charges against them. A lot of them are heading for bankruptcy, saddled with absurdly inflated expectations and far too little capital as the Wall Street bros took as much as 65% of it in some deals. After pumping, Hyzon was briefly worth $850 per share. Now its stock, soon to be delisted, is worth $1.12. The Wall Street bros made out like bandits.

Hydrogen and hydrogen transportation was a theme among SPACs. Nikola Corporation went public in June 2020 through a SPAC merger with VectoIQ Acquisition Corp., valued at approximately $3.3 billion. Shortly after, the company faced fraud allegations from the aptly named Hindenburg Research in September 2020, claiming Nikola had misled investors about its technology and capabilities. Investigations by the SEC and DOJ followed, leading to the conviction of founder Trevor Milton in 2022 on three counts of fraud. Nikola agreed to pay a $125 million fine in 2021 to settle SEC charges for deceiving investors through misleading public statements.

Who doesn’t remember Nikola’s lovely video of a hydrogen truck driving along a highway that was faked by towing the truck to the top of a hill and letting it roll down from there? Par for the course for hydrogen transportation plays.

Hyzon Motors misled investors by making false statements about its business relationships and vehicle sales. The company falsely claimed to have delivered its first hydrogen fuel cell electric vehicle in July 2021, even releasing a misleading video suggesting the vehicle was operational on hydrogen when it was not equipped for that. Additionally, Hyzon reported selling 87 FCEVs in 2021, when in reality, no such sales had occurred that year. These actions led to settled fraud charges by the SEC in September 2023.

But now its false claims — “Delivering heavy duty transport, without emissions” — are gone. At least it won’t be charged with false advertising for its greenwashing, so there’s that, I guess. As I always say to good engineers and others in hydrogen firms, get out now or at least start getting out. It’s going to end badly and you aren’t actually doing anything for the environment.

Chip in a few dollars a month to help support independent cleantech coverage that helps to accelerate the cleantech revolution!

Have a tip for CleanTechnica? Want to advertise? Want to suggest a guest for our CleanTech Talk podcast? Contact us here.

Sign up for our daily newsletter for 15 new cleantech stories a day. Or sign up for our weekly one if daily is too frequent.

CleanTechnica uses affiliate links. See our policy here.

CleanTechnica’s Comment Policy