Sign up for daily news updates from CleanTechnica on email. Or follow us on Google News!

In the past few weeks, three hydrogen transportation firms have declared bankruptcy. First in the set of dominos was German firm Quantron, which left IKEA Austria holding a fleet of its hydrogen delivery vans as well as a fleet of its inferior-to-competitors’ vans without warranty, parts, or maintenance. The other day, I published a piece on the unsurprising bankruptcy of Hyzon, a hydrogen freight truck startup. In that piece, I said that it was going to be a bloodbath in the sector in 2025 as the reality sunk in that hydrogen would remain too expensive, fuel cell vehicles would remain unreliable, and actual greenhouse gas emissions were much higher than hyped.

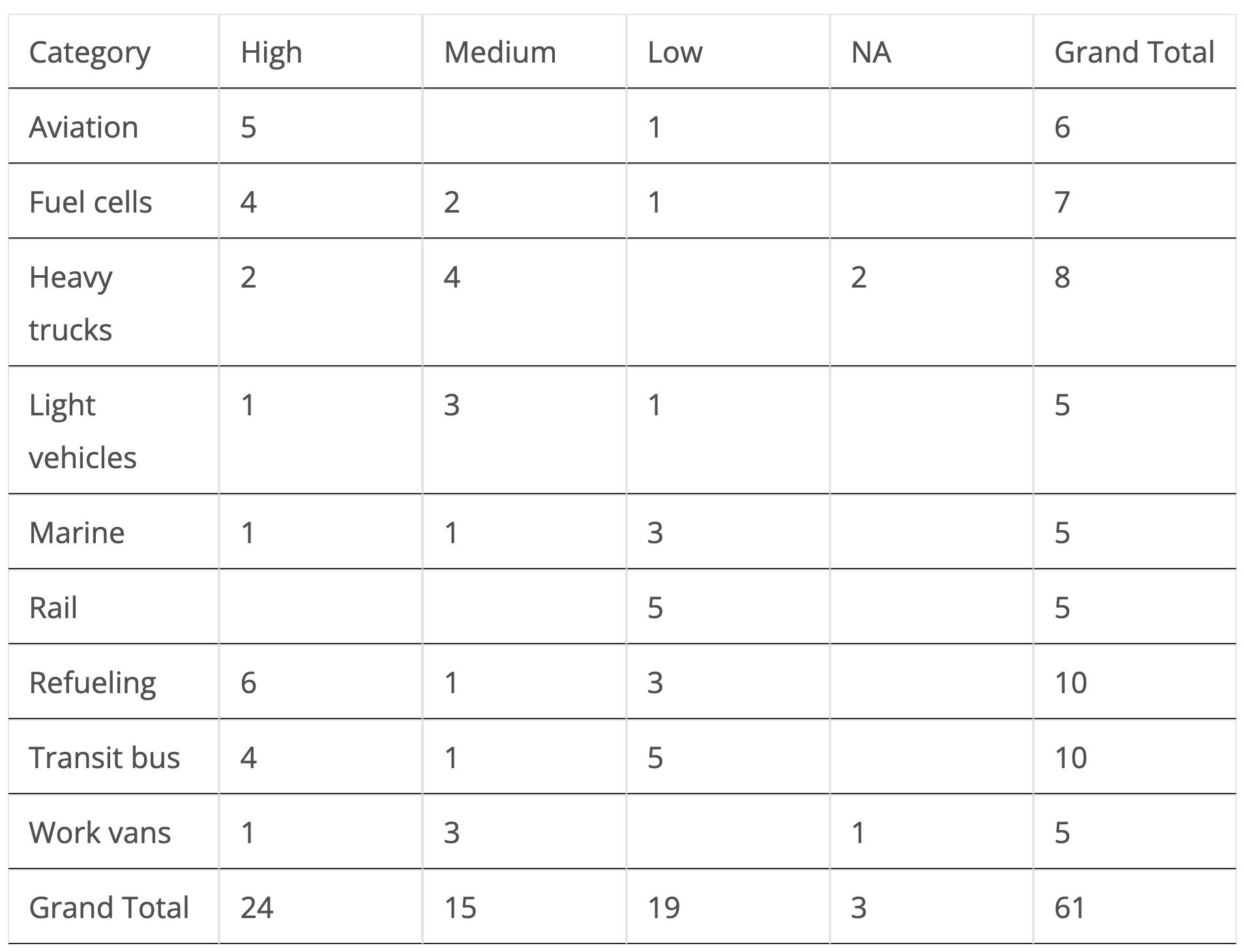

Today, I spent a bit of time putting together a list of firms involved in different aspects of hydrogen for transportation, from refueling to fuel cells to different types of vehicles. I identified over 50 companies in this initial pass, with some like Toyota showing up in more than one category, and I’m sure I missed a few. Then, I went through and categorized them by whether they were in pre-production, operation, or bankrupt, and assessed them all for degree of risk to their survival in the coming year.

Note that I don’t have electrolyzers or hydrogen storage manufacturers on there, although I’m sure many of them are at risk as well. The reason is that green hydrogen will be essential for decarbonizing hydrogen used as an industrial feedstock for things like ammonia fertilizer, hydrotreating biofuels, and at least some green steel. My projection of end-state demand is around 80 million tons a year, so the ones that are counting on 600 million tons a year are going to be very disappointed, but eventually we’ll be making the stuff. Firms that make components required for industrial feedstock use of hydrogen are at risk simply because the financials are hard to have make sense today, but they are actually doing something useful.

Not hydrogen for transportation firms. They are all wasting money in a dead end pursuit based on really quite bad assumptions that aren’t based in empirical reality. As many of us have been saying for years, bringing receipts for why the economics don’t add up, hydrogen is remaining expensive and doesn’t have the conditions for success to get cheaper.

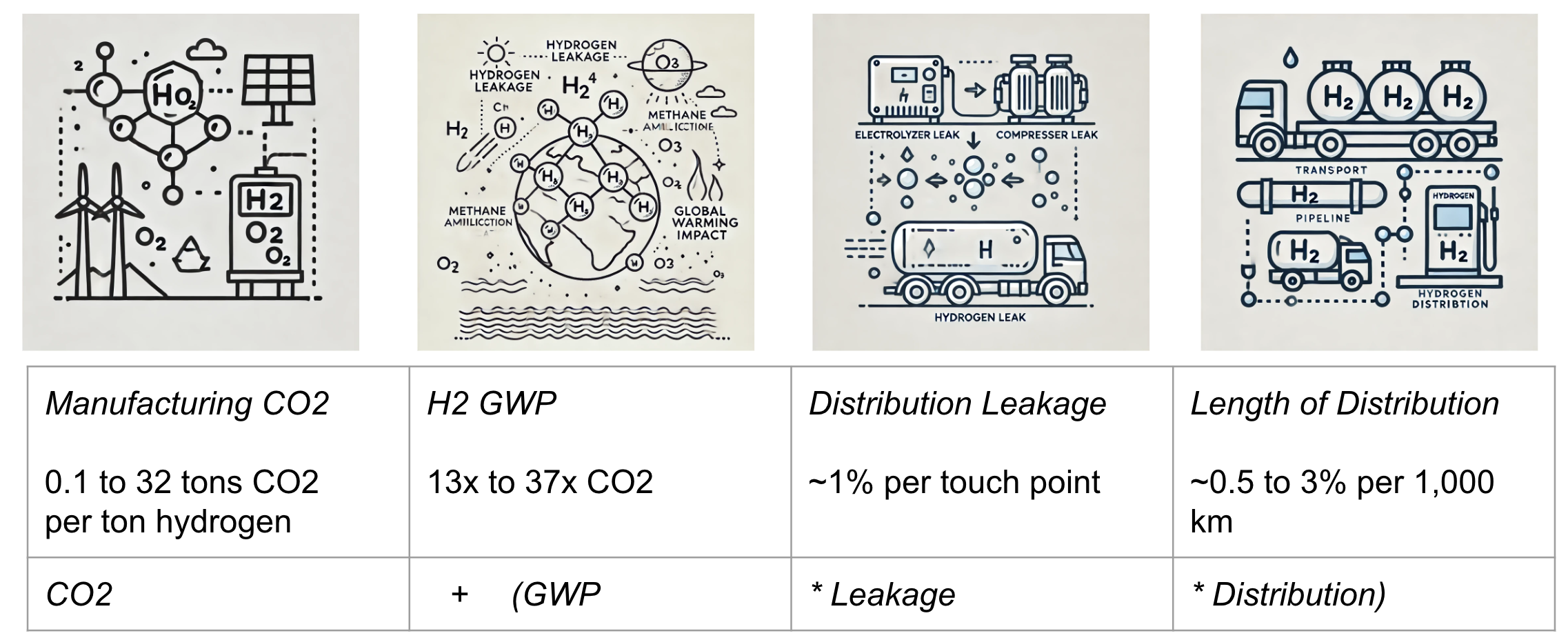

And as many atmospheric scientists have been saying for about 25 years, hydrogen prevents methane from breaking down as quickly, so causes atmospheric heating indirectly. That was finally quantified in a 2023 Nature paper and found to be 13 to 37 times the potency of carbon dioxide, depending on whether 100 or 20 year global warming potentials were considered.

Of course, we’ve always known it leaks, but we haven’t been measuring that in any sort of systematic way. Now peer reviewed and governmental reports are making it clear that it leaks a lot, about 1% or even more per touch point in the value chain. Make it beside an industrial scale Haber-Bosch ammonia synthesis reactor in the amounts required for the process when the hydrogen is needed and leakage can be pretty low. Make in small electrolyzer in a bus depot and leakage will be high. Make it and then transport it any distance to put into vehicles to refuel them and leakage will be very high, likely in the 10% range.

Of course, this means that hydrogen transportation plays have tended to run a bait and switch, claiming that they’d be using green hydrogen, but that ended up either being green hydrogen trucked in from a long, long way away — 4,500 kilometers for the Whistler bus trial that ended a decade ago and 1,300 kilometers for Norway’s sole hydrogen ferry — with very high leakage en route and diesel truck emissions to boot, or made from natural gas and trucked anyway, adding more emissions. My sample of case studies of likely total greenhouse gas emissions for passenger transit situations has ranged from 15 times higher than electric buses in Winnipeg’s initial plan to 90% of diesel buses in Ontario to double diesel ferries in Norway to an extraordinary 3.2 times diesel buses in Winnipeg’s new plan.

So far, expensive fuel that leads to high emissions. Not exactly what was promised.

But it gets worse. Hydrogen vehicles are less reliable than diesel and battery electric vehicles as well, per information from the US Department of Energy’s publications on California’s buses and the EU’s annual status reports on their hydrogen project funding. And hydrogen refueling stations are constantly failing, with California’s 55 in 2021 being out of service 20% more hours than they were actually pumping hydrogen and Quebec’s being out of service for a full third of all the hours in the four years of their trial.

That’s why there are more transit operators who ran hydrogen trials and abandoned the technology than ones operating them. That’s why hydrogen passenger rail trials are ending in failure. That’s why maritime hydrogen power is a litany of failures. And that’s why firms like Quantron and Hyzon were doomed.

It’s in this context of the continued failure to improve any of the above, with the recent quantification of greenhouse gas emissions and leakage rates actually making hydrogen even worse than it already is, that I predicted 2025 would be the year a lot of the firms that were committed to the space would end up defunct.

But like Quantron and Hyzon, First Mode couldn’t even limp into the new year. It was founded in 2018 in Seattle, Washington, with the goal of developing sustainable solutions for heavy industry. The company focused on integrating hydrogen fuel cells and batteries into industrial machinery, including mining trucks. It partnered with Anglo American to create the world’s largest hydrogen-powered mining truck.

Anglo American is a multinational mining company headquartered in London that specializes in the extraction of metals and minerals, including platinum, diamonds, copper, and iron ore. The company made significant and wasted investments in hydrogen technology. In addition to partnering with First Mode, it invested in Horizon Fuel Cell Technologies to establish HET Hydrogen Pte Ltd. Horizon is privately held and spun off Hyzon in 2020, so Anglo American was involved in both of these failures, although possibly tangentially. HET focuses on manufacturing megawatt-scale hydrogen electrolysers for applications in transport, steel production, and fertilizer manufacturing, leveraging Anglo American’s expertise in platinum group metals critical for proton exchange membrane (PEM) technology.

In 2023, major mining companies Fortescue, BHP, and Vale announced commitments to adopting battery-electric mining equipment as part of their efforts to decarbonize operations. Fortescue accelerated the transition by focusing on electrifying its mining fleet and developing supporting infrastructure, after spending years promoting hydrogen as the answer. BHP partnered with leading equipment manufacturers to integrate battery-electric solutions into its operations, aiming to reduce its reliance on diesel-powered vehicles. Similarly, Vale launched pilot programs for battery-electric haul trucks and loaders at several sites, aligning with its broader goal to achieve net-zero emissions by 2050. These declarations marked a significant shift in the mining sector toward electrification and renewable energy integration.

In 2024, Fortescue made substantial investments in electric mining equipment. The company signed a $2.8 billion agreement with Liebherr to purchase 475 zero-emission machines, including approximately 360 battery-electric autonomous trucks, 55 electric excavators, and 60 battery-powered dozers, replacing two-thirds of its existing mining fleet in Western Australia. Additionally, Fortescue placed a $400 million order with XCMG for over 100 electric-powered heavy mining machines.

The writing was on the wall for hydrogen powered mining equipment, so First Mode’s demise isn’t a surprise. It was a bit quieter than Hyzon in its passing, mostly because it was a privately held company, not a cleantech SPAC debacle with serious pump and dump transgressions that led to SEC charges. But still, it’s gone now.

Next year most of the high-risk companies and a few of the medium risk companies I’ve identified are likely to be gone as well. For the people who are going to lose their jobs and the investors who are going to lose their money, all I can say is that people like me have been telling you that’s what was going to happen for years. Your time, talent and money could have been doing something much more useful for the past few years and you wouldn’t be nearly as stressed out.

Chip in a few dollars a month to help support independent cleantech coverage that helps to accelerate the cleantech revolution!

Have a tip for CleanTechnica? Want to advertise? Want to suggest a guest for our CleanTech Talk podcast? Contact us here.

Sign up for our daily newsletter for 15 new cleantech stories a day. Or sign up for our weekly one if daily is too frequent.

CleanTechnica uses affiliate links. See our policy here.

CleanTechnica’s Comment Policy