There are really obvious solutions to big problems. One of those solutions is putting batteries in shipping containers and winching them on and off ships to power electric drivetrains. Recharge the containers on land in transshipment ports and winch them onto the next ship or train that needs one.

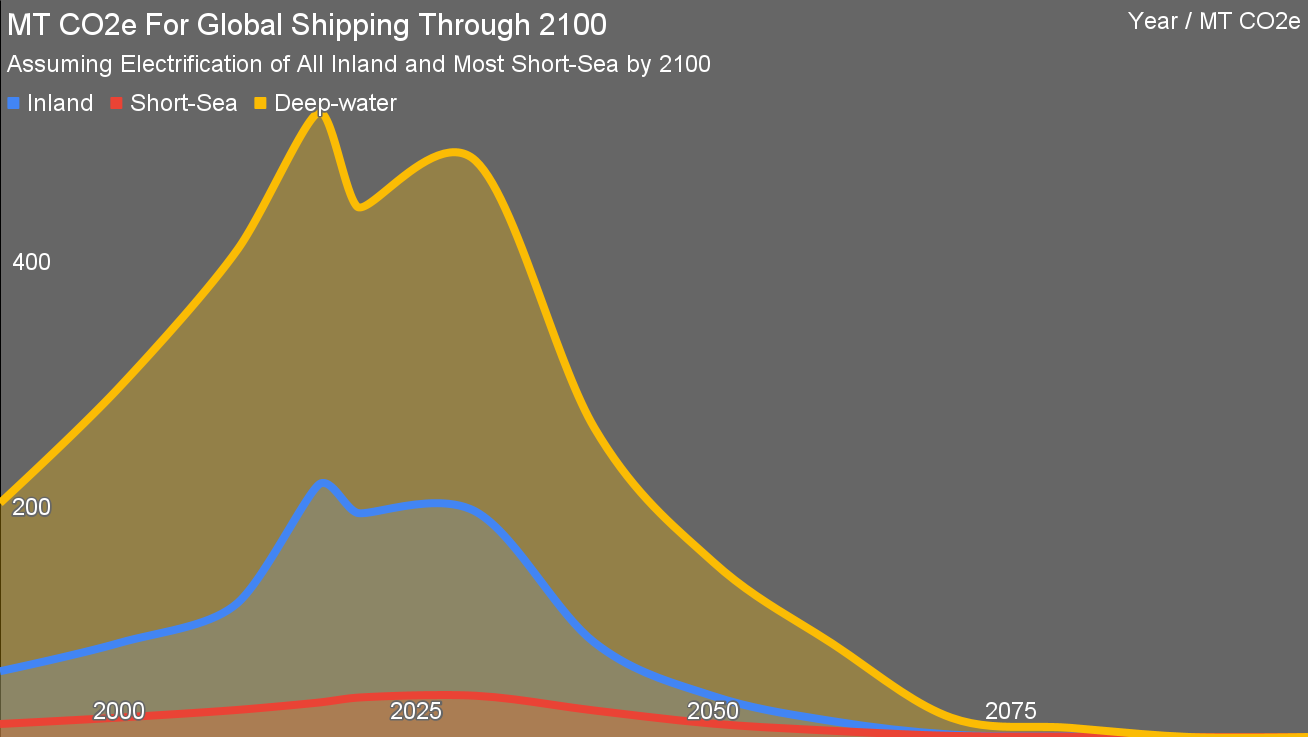

I’ve been projecting this as a core part of my decade-by-decade maritime repowering scenario through 2100. In my opinion, all inland shipping and two-thirds of short sea shipping will be fully electric. The remainder will be biofuels. Hybrid electric with biofuel generators is a very likely pattern for all three categories of shipping — with ships steaming into and out of ports, and waiting to load and offload running solely on batteries for higher efficiencies at variable speeds, elimination of port air pollution, and reduction of port noise being core benefits.

I discussed this with Elisabet Liljeblad, PhD, Stena Teknik’s sustainability and energy lead, recently as part of a lengthy conversation on my Redefining Energy – Tech podcast (part 1, part 2). Liljeblad’s organization does the engineering, design, and technical strategies for Stena Sphere’s maritime business line, a multi-modal organization that includes ports, ferries, roll-on roll-off freight ships, roll-on roll-off freight and passenger ships, and bulk carriers. I spent time with the Stena global technical leadership team in Glasgow as part of a debate on maritime decarbonization that they’d invited me to participate in, and as I said at the time, battery energy density was going to be sufficient by 2040 to power all of their regularly scheduled routes.

And now, a proof point. The Yangzhou shipyard in northern China, inland from Shanghai on the Yangtze River, just launched an electric-drive-only 700 container ship which will ply a regular 1,000-km (600-mile) route up and down the river and to the world’s largest container port on the Yellow Sea.

It’s not going to run all the way on batteries it carries onboard, of course. Battery energy density is increasingly good and will be multiples of today’s in the coming years, but steaming 1,000 km upstream, even in the 3.6-kilometer-per-hour average water speed of the Yangtze, is a huge energy requirement. It doesn’t have to, as there are 30 container ports along the 2,700 kilometers of navigable waterway (about twice the length of the Mississippi and three times the length of the Rhine).

And 36 containers of batteries will be dispersed through those ports in some undoubtedly optimized pattern to allow the ship to slip into a berth and then winch depleted batteries off and charged batteries on. The containers are reported to have a capacity of 50 MWh of batteries in multiple reports, which might or might not be accurate. The reason I say this is that Tesla’s original Megapack is almost exactly a standard shipping container in size, and it can store 3.9 MWh.

I suspect at some point a digit in the report of kWh capacity was slipped and it has been repeated since, and that the containers actually have 5 MWh each. Total battery capacity for the system initially is either 180 MWh or 1.8 GWh. (If anyone close to the project has confirmation one way or the other, please share.)

The ship isn’t huge by container standards either. It’s an inland ship, so only 119.8 metres (393 feet) long and 23.6m (77 feet) wide, with a 10,000-metric-ton full load capacity (deadweight tonnage or DWT). It’s bigger than a football field whether it’s American football or real football, so non-trivial, but it’s nowhere near the size of the big transoceanic ships. The biggest of those right now, the MSC Irina (also built in a Chinese shipyard, by the way) can carry over 24,000 containers and is over three times as long as the river ship.

If that seems like a lot of batteries and containers for a single ship plying the Yangtze, you’re be right. A sister ship will be launched shortly, and the plan is for vessels on the entire Yangtze to be electrified. As half of the world’s inland shipping is in China, and the Yangtze is by far the biggest inland shipping route, that means that this ship is the lead vessel in electrification of about half of all inland shipping.

It’s unclear at present if every ship will be electrified and in what timeframe, but I suspect it will be all of them and sooner than anyone expects. After all, China has perhaps 600,000 electric buses and 500,000 electric trucks on its roads, 40,000 km of high-speed electrified freight and passenger rail (with 10,000 km more under construction or planned), and most of the world’s battery critical minerals processing and manufacturing facilities.

The ship’s operator, Cosco Shipping, is a key founding member of the Electric Ship Innovation Alliance, an organization with over 80 members, including firms which provide electric-powered propulsion, vessel design and construction, port and terminal operation, scientific research, electric-power batteries, and industry investment and financing. The launch featured a full set of national and provincial representatives, indicative that this joint effort to decarbonize a major domestic supply chain is being treated as a major strategic effort.

It’s also worth noting that while the biggest ship manufacturer in the world is South Korean, China leads global shipbuilding by a comfortable margin, building about 44% of all ships compared to South Korea’s 32%. China has the domestic capacity to build every ship and to put batteries and drivetrains into them. As a reminder, China’s domestic supply chain also has a very significant purchasing power parity advantage, as its yuan goes 40% further than western currencies do inside their country when buying domestic goods and services. They’ll be not only building electric ships for themselves, they’ll be building them for everyone else as well.

At present, I’m unaware of any other country or region which has anything remotely equivalent in place in terms of a national and provincial strategy, never mind the capacity to execute. Europe and North America have barely started to consider inland shipping decarbonization, and the USA’s new transportation blueprint has exactly one goal related to shipping, that “5% of the global deep-sea fleet are capable of using zero-emission fuels by 2030.” As I said in my assessment of the blueprint, they are missing the boat.

There’s a much smaller version with a similar vision to this in Holland with Zero Emission Services (ZES). The organization’s shares are held by electric bus firm Ebusco, Dutch insurer ING, maritime technology company Wärtsilä, and the Port of Rotterdam Authority. There is national and provincial backing, so there’s that. And they’ve had a small 36-container ship running beer 50 kilometers for a couple of years. I’ve communicated with a couple of the people, as they reached out after my initial publication of my maritime decarbonization scenario. They have the right vision and some good partners, but they aren’t an EU strategic initiative with over 80 major firms. There’s an unrelated electric, autonomous, 120-container ship, the Yara Birkeland, sailing about 10 kilometers carrying fertilizer in Norway as well.

China’s inland shipping, 50% of all inland shipping worldwide, will be decarbonizing rapidly given its national and provincial strategic decarbonization focus, its domination of shipbuilding, and its domination of battery supply chains. The rest of the world will be far behind unless they get their oars biting into the water soon.

I don’t like paywalls. You don’t like paywalls. Who likes paywalls? Here at CleanTechnica, we implemented a limited paywall for a while, but it always felt wrong — and it was always tough to decide what we should put behind there. In theory, your most exclusive and best content goes behind a paywall. But then fewer people read it! We just don’t like paywalls, and so we’ve decided to ditch ours. Unfortunately, the media business is still a tough, cut-throat business with tiny margins. It’s a never-ending Olympic challenge to stay above water or even perhaps — gasp — grow. So …