Sign up for daily news updates from CleanTechnica on email. Or follow us on Google News!

A great deal of digital ink has been spilled on Tesla laying off a lot of its Supercharger team recently. I’m not in the business of commenting on Tesla and Musk’s every twitch and tweet, so I don’t have fourteen hot takes already. But I have a hypothesis and it involves camels, sponges, spectators, and transitions.

Like a lot of people who grew up outside of the affluent trust-fund set, I have a broad variety of experience to draw on from my career. One of my many part-time jobs to pay for education, rent, and food was being an officer in the Canadian military reserves. An early professional job was running logistical deployments of telecommunications and computer systems for one of Canada’s major banks, the largest of which was 32,000 devices over 1,400 physical locations in 10 months.

Another part of my career was assisting corporations’ information technology divisions to undergo the spasms of transformation that they require every eight to twelve years with major changes in mergers, deployments of major new systems, or adoption of new technologies and paradigms. Another part of my career was as a technology development methodologist and estimation expert. Another part of my career, overlapping with the others, was business and technology strategy. And another part of my career was a major project and contract startup, transition, and fix-it guy for a global technology giant.

Along the way, not satisfied with the rather absurd numbers of things I was learning professionally, my hobbies progressed through skiing to snowboarding, windsurfing to kitesurfing and wing-foiling, three variants of unicycling, a couple of variants of juggling, Texas Hold’em ring games to tournaments to online, paragliding including the southern cliffs of Bali, 3D NURBs-based modeling of furniture and consumer products, building furniture, acting and improv and a few things I’m just not remembering as I type this. I also picked up another degree to go with my computers and business BSC in my spare time, English literature with a minor in environmental studies. The relevance of the hobbies will become apparent in a minute.

It took me quite a while to develop the self- and domain-knowledge to be able to forge my current niche, where I have the freedom to explore whichever domains of climate change and solutions I consider both material and interesting, project solution sets out into the future, and have clients engage me to assist them with their investment and business strategies in alignment with where the ball is going to be, not where it’s currently headed.

This gives me a perspective which is broader than many and provides me a lens through which I am viewing the question of the Supercharger team.

One of the metaphors I’ve been using for perhaps 20 years is that of the camel, the spectator, and the sponge. I stumbled across it on the internet a long time ago, and it’s been a useful part of my professional toolkit since. It’s not original to me. It might be original to Richard Flint, who has a page on it, or it might be he found it somewhere as well.

Imagine, if you will, a swamp full of mud, weeds, occasional shaky tufts of ground, insects, and leeches. On one side of the swamp, there’s a brickworks. On the other side, there’s a building site. You’re running the show, and you have a problem. You need to deliver bricks to the building site, but there’s no road or bridge across the swamp and it’s not deep enough for barges. What do you do?

You find a sponge. A sponge is a person who loves new things and challenges. You tell the sponge, take ten bricks to the building site every day. You don’t tell them how, you just give them a target and let them go.

The sponge looks at the bricks and looks at the swamp. They grab a couple of bricks and set out. They trudge through some mud to a tuft of shaky ground. They end up neck deep in water at one point and have to back out. They fall in completely and lose a brick. Eventually, they get to the other side and drop a brick off. Then they return.

They keep doing this, day after day for a month. Every day, they make the route a bit better. They use some bricks to shore up a chunk of ground. They drag some sticks and logs along and create paths. At the end of the month, there’s a fairly dry path across the swamp.

Now it only takes a couple of hours in the morning for the sponge to deliver ten bricks to the site. They are bored. They are losing interest. Possibly they’ve taken to pestering people in the brick works about the different types of insects and leeches they’ve discovered in the swamp, disrupting their work.

Now it’s time to find a camel. A camel is a person who loves having a routine, a job, and a known path and stable targets. You tell the sponge, teach the camel the route across the swamp. Help them get across the path the first couple of times. Fix stuff that the camel balks at, perhaps a pole vault or rope swing that’s just a bit too much.

Tell the camel, take 100 bricks across the swamp to the building site every day. They happily do, learning the route, loading up hod after hod with bricks and trudging back and forth across the swamp for months until the building site doesn’t need bricks any more.

Meanwhile, there’s a spectator in the mix. They sit on the side of the swamp and watch all of this. Every time the sponge falls in, they laugh at them and say, I could have told you that was going to happen. Every time the camel walks by, they ask them, how can you bear such a boring job?

The moral of this story is, if you have a swamp you have to figure out how to get through, get a sponge. When there’s a consistent and well-defined path through the swamp, the sponge will get bored and possibly destructive, so squeeze them out on a camel and then throw them at a different swamp. Reward the sponge for the path and the camel for delivering the bricks.

Shoot the spectator.

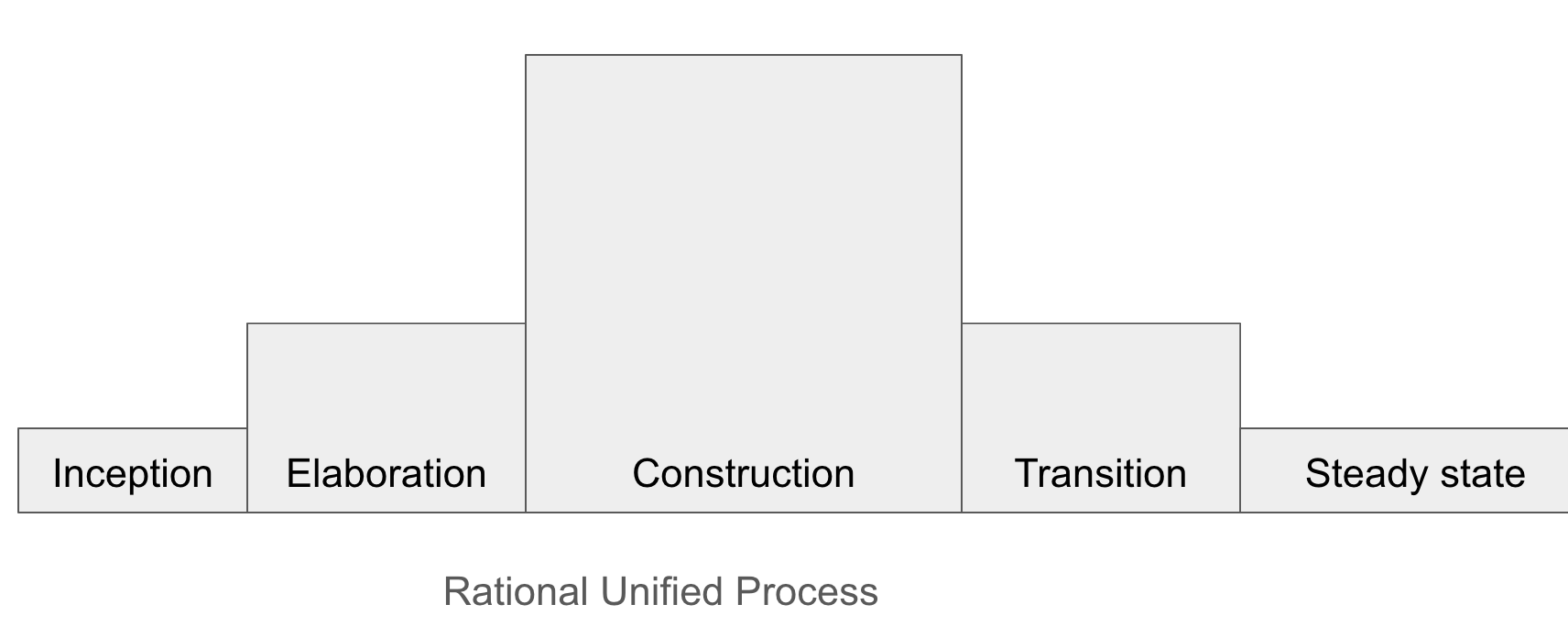

For a couple of years in the methodology phase of my career, I was the senior product manager in charge of the Rational Unified Process, first in Rational, a Silicon Valley startup, and then in IBM after it was acquired. It’s a useful explanatory framework for discussing Tesla’s Supercharger team vs other Tesla teams.

Inception of a project or startup is all about trying to figure out if there’s a business case or value proposition and identifying roughly how you think you’ll solve the problem and especially identifying all of the risks you can think of. It’s all sponges with the exception of a small administrative group who make sure everyone has basic tools like security badges and that they get paid on time. There’s an off-ramp in there if there is no viable business case.

Elaboration adds a bunch more sponges. Each sponge or group of sponges is given a chunk of the solution in context of the entire solution to flesh out more conceptually, and specifically to tackle identified risks from highest magnitude to lowest magnitude. Lots of pilots, trials, and failures. They are also finding out a bunch of stuff that wasn’t thought of during inception. Lots of planning, scenarios for delivery, firming up of budgets, building of frameworks and processes for construction occurs here, so that when construction starts, it will run smoothly. There’s an off-ramp in there if there is no viable business case.

For those who have read Bent Flyvbjerg’s How Big Things Get Done, inception and elaboration are the thinking slow part of initiatives. For those who haven’t read it, you really should.

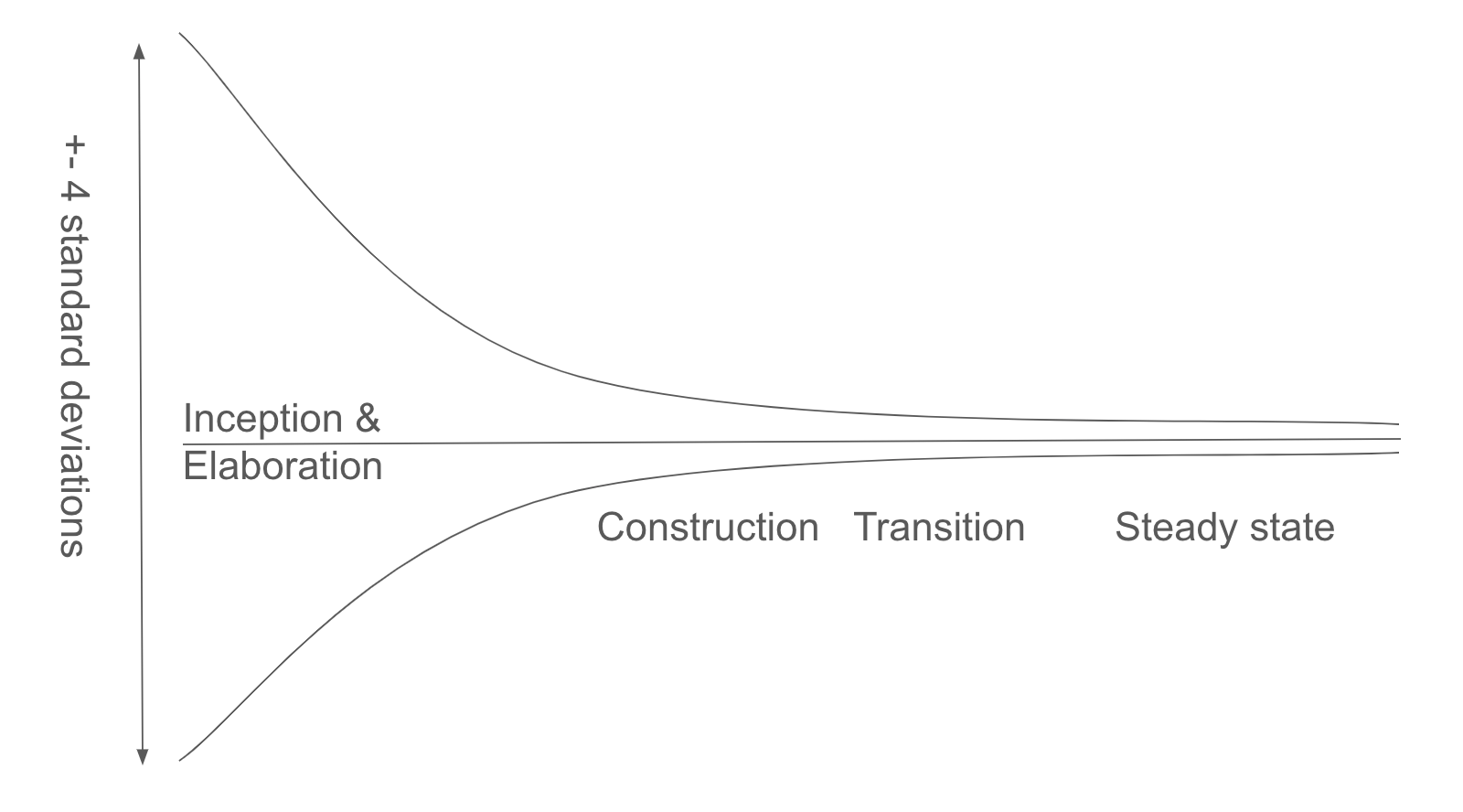

Why all that time and sponge-power spent on inception and elaboration?

At the beginning of complex technical projects with big objectives, the degree of business case and technical uncertainty is very high. Risks are very high. Timelines are completely uncertain. You have to spend concerted effort on driving down risk and uncertainty.

Then comes construction. A lot more staff are added. A lot of them are camels, but typically a few more sponges get added. The sponges from inception and elaboration are around to turn those rope swings and pole vaults into pathways, but aren’t doing the heavy lifting. This is the acting fast part of Flyvbjerg’s approach to megaprojects.

If inception and elaboration are done well, construction goes smoothly, and the off-ramp to project close-out doesn’t get taken.

Then transition. Some camels from the construction phase are dropped off of the team and some camels are added to work in the steady state team. A few sponges are around because something always goes wrong.

And then steady state. Some camels persist. Possibly one of the staff who is on the continuum somewhere between camel and sponge persists because something always goes wrong that needs someone competent to look at new problems and solve them. Steady state can mean shipping massive amounts of software or hardware products every month. It can mean that a big chemical plant is in full operations, producing a thousand tons of product a day. It can mean that there’s an entire marketing, sales, manufacturing, and distribution organization humming over delivering the same stuff to customers globally. Steady state just means that startup is over and full commercial operations are running.

Who else joins the team in transition and stays for steady state? Operational efficiency hard cases. These are the people who slowly and incrementally streamline and refine every process and practice until the organization is lean and efficient at delivering the same things time after time with lowest costs, highest quality, and hence greatest profits.

Typically, I was brought in to run inception and elaboration phases, and later to structure out multiyear programs during sales efforts, then to help launch the program, and then brought in as new phases started to help with the change in approach, and often as a fixit guy when thing went off the rails due to any one of the thousand reasons projects go off the rails. When no one else could figure out why things weren’t working in projects across Canada and the USA, often I’d be the person on a plane to go figure out what was failing and what to do about it so we could kill projects or fix them. One memorable Edmonton project had seen eight project managers leave, and the ninth, the practice’s superstar, threatening to quit before I showed up and did some organizational aikido over a couple of weeks, enabling the superstar to run a very successful project.

Every shift of focus for every one of those phases and into steady state was an opportunity for failure. Every one was emotionally challenging for the people involved because relative importance and work priorities changed. The feted sponges from the beginning of the project were being kept around twiddling their thumbs, and sometimes that meant that they had become the problem that needed to be fixed. Camels hate change, and transitioning from project mode to steady state mode usually meant different managers and often different offices.

After a few years of steady state, only operational efficiency types and camels are left. Anyone with an inkling of spongeishness either left or is working in a fugue of depression because they need a paycheck, all of their creativity and problem solving being reserved for extracurricular activities like maker fairs, fantasy football, part-time startups, extended Dungeons and Dragons campaigns, dreams of being an author, and the like.

And then business conditions or executives would change and transformation would again be required. That happened every eight to twelve years in IT shops, from my perspective. In shops like transit and utility organizations, it happens every 20 to 30 years.

But there are no sponges left in the organization. It’s all camels, Six Sigma efficiency gurus and ISO 9000 quality control experts. They don’t have the conditions for success for transformation inside the organization, so they have to bring experts from outside the organization. When the dust settled, typically the new organization had 20% of the people who embraced the change and increased their organizational clout, 60% of the people who adapted whether graciously or not, and 20% of the people who stayed on to sabotage the efforts — spectators — or left under their own steam or otherwise.

In one memorable fixit exploration, I found that a legacy spectator that everybody in the organization I worked for had dismissed as a powerless redneck had quietly, strategically effectively, and efficiently removed almost every one of the conditions for success for our organization. Fixing that took top level leadership discussions and a lot of work. When I returned to that organization for a transformation years later, the spectator was still around, and one of the key risks on my internal register was ensuring that they were contained in some way, something which included a bunch of off the record conversations with senior people in my company and the client.

If it’s not abundantly clear, I’m all sponge, no camel. That’s what the litany of hobbies and careers illustrates. Whenever I’ve ended up overstaying the sponge phase, or in jobs where sponges are required under 50% of the time, I’m usually unhappy and don’t make things better. My life partner knows the signs and has asked a few times when she starts seeing them if it’s time for a change.

This AI-generated image — by OpenAI tools, a firm Musk was one of the primary founders of, although he had to step aside a few years ago for conflict of interest with Tesla AI efforts — is a bit of an exaggeration of how Superchargers are delivered and installed on sites, but not much of one.

A Supercharger sales organization fields requests from innumerable retail places that want Supercharges in their parking lots and does strategic growth planning along well-established pathways. They pick the next spot and sign the contracts, handing it off to operations types who deal with site preparation, getting the new site into the stable and existing Supercharger site software which is integrated with the stable and existing Tesla trip planning software, Google, ChargePoint, and the like. They work with local contractors to get city approval for the electrical changes, get local utilities to provide the right amount of electricity to the site, and wire the sites in readiness for the Superchargers.

Superchargers are manufactured in factories on poured slabs of cement with all of the wires and power electronics and battery buffers in place, and tested there. They are loaded onto trucks with cranes and at the Supercharger site, the crane on the truck lowers them to the ground where they are plugged in and tested. Probably the local contractor arranges for city inspections at this point as well. A bunch of paperwork and forms are signed off. The contractors get paid and hopefully thanked, the truck driver is long gone, and a button gets pressed in the Supercharger administrative software indicating it’s live, at which point it shows as live in all of the downstream software.

There are no sponges in this process anywhere. There are only camels and efficiency experts. The sales people are order takers. The ‘strategists’ aren’t inventing strategy or changing anything, they are just extending and adapting to new geographies somewhat.

There are approaching zero technical or engineering risks in any of this. There are logistical challenges, regulatory hurdles, contractor screw-ups, incompetent camels and the like, but virtually nothing that would keep a sponge entertained for more than a day every week or four.

When it was formed, Tesla was in inception. The Roadster was purely an elaboration phase exercise, done to figure out the risks, to make mistakes and to prepare the way for more. And they did, realizing that retrofitting existing vehicles for batteries was exactly the wrong tactic, increasing and not decreasing risks, something that’s lifeblood for Tesla these days and something a lot of OEMs still haven’t figured out.

Each component of the solution, including the Gigafactories, Model S, X, 3, Y, Cybertruck, and Supercharger teams, were full of sponges. Where ever possible, Tesla made automation and robotics do the work of camels, to maximize labor efficiency and minimize cost of manufacturing. Sometimes that led to failures like the robots that couldn’t pick up fluff consistently and had to be replaced by a camel… er, human.

Those sponges kept improving on the products without the products being rebranded as new models. Over-the-air updates were constant and added incredible things like greater acceleration and greater range. Sometimes that sponge-y willingness to do new things led to very odd things like the farting option and pretty much everything to do with the Cybertruck.

Superchargers went from strength to strength, getting more juice through the cables more quickly and safely, adding liquid cooling and now delivering megawatt-scale chargers. The Tesla plug is now the standard in North America.

Tesla’s Superchargers are globally preferred because they had sponges do their jobs, and they have had camels — operational efficiency and quality experts — do their jobs.

The difference between a bored sponge and a spectator is hard to tell. The only way to find out if you don’t know them is to throw them into a swamp to deliver bricks. If they thrive, they are a sponge. If they flail, moan, point out other people’s mistakes and never get across the swamp, they are a spectator.

Bored sponges are often as destructive as spectators. In steady state, bored sponges want to fix something, but ‘fixing’ stuff which isn’t broken breaks it, at least in the eyes of downstream users and deployers. About half of all ‘improvements’ to user experiences on apps on mobile devices and the web are things which break things from the user’s perspective and create negative value, not positive value. After a certain point, users just want toasters to toast bread, not ask if they want AI help with bread toasting optimization.

The Supercharger business is a mature, steady state operational business. It’s growing rapidly still, but it’s deploying exactly the same product in highly optimized ways using exactly the same processes and software. It’s dealing with challenges, but the challenges aren’t challenges sponges like, they are filling in city approval forms correctly and getting contractors to show up and put wires in place. They are fulfilling orders in a work management system. The sales people have a standard contract that never changes that they sign with hosts.

Not so for the autonomous driving team, which is still struggling with the massively difficult problem of getting to a deployed, stable, end-game solution. The cone of uncertainty at the beginning of this path was very broad. Tesla famously didn’t choose to use lidar, something I agreed with at the time, and worked from a subsumption robotics approach as opposed to the full world model approach used by Google at the time, something I also agreed with.

They have constant user feedback with their self-driving functions, but not for Autopilot and Autosteer so much these days. Full self-driving, an aspirational name, still has lots and lots of user feedback as a requirement to tune the models and find edge conditions. They’ve eliminated radar as well, which eliminated a lot of complexity of sensor feedback.

Most recently, they’ve merged the city and highway models into a single model and eliminated a lot of classical robotics coding in the middle to make that work.

Full self-driving is now in the construction phase in my opinion, and not in the transition phase. Enormous numbers of high-quality sponges are still required for the full self-driving team.

For the Supercharger team? Not so much. Barely at all.

As part of my particular professional journey I’ve been engaged with three or four global standards, a couple of times trying to implement solutions that leveraged early stage, high-variance, academic standards and providing feedback on the results to the standards organizations as I broke their crap apart to find something useful in it. Once a standard is in place, sponges should keep away. That’s ISO 9000 quality control and efficiency expert land. Sponges want to improve things, which means deviating from the standard. For mature standards, that’s usually a mistake.

The Supercharger team, in this analysis, still had a lot of sponges and likely sponge executives. Lots of sponges were in senior and operational roles. They were quite probably making it really hard for the operational efficiency and ISO 9000 heads to do their jobs. As bored sponges, they were probably creating problems within the Tesla organization instead of delivering Superchargers as effectively, efficiently and cheaply as possible.

As far as I can tell, this is the first part of Tesla to transition to a steady state organization that didn’t need sponges. It’s possible that this is the first time Musk has every actually managed a transition to steady state. It’s not his thing.

Musk is an uber-sponge. He loves inception and elaboration. He loves other sponges and is constantly throwing them into swamps, which they love. He’s hard on them in ways that they like, for the most part. Sponges want to work for Tesla (and SpaceX and OpenAI) and face new, exciting, and interesting challenges every day.

Musk doesn’t appear to like camels at all. If he could build something with a team of sponges in an office and bunch of robots in a factory with no humans at all, he would. But he delivers stuff in the real world, where operational efficiency wonks and ISO 9000 quality controls are an absolute must.

I’m pretty sure that the Supercharger team has been struggling mightily with this transition to steady state for a year or two. It’s quite possible that the executives — probably sponges, remember, but highly paid sponges who are feted globally for the quality of their deliverables, and sponges surrounded by other sponges they really like working with — have been resisting the transitioning and streamlining of their organization and the ascension of camels to all the powerful and influential positions.

I’ve dealt with innumerable transitions between phases of projects and into steady state, and leadership needs to be brought carefully onboard early and carefully for it to be a remotely smooth process. The people who aren’t the right ones for a steady state have to be given soft landings and lots of thanks. The new people onboarding have to be welcomed and carefully shown the ropes, as remember, they are camels.

Even with the best of care, these transitions fail as often as they succeed. They are stressful for all involved.

Sometimes, after there has been a disastrous failure, the only option is to stop completely and bring on a new team. I’ve shut down projects and restarted them a year later, with carefully selected members of the old team.

This smells like that, except at Silicon Valley speed, with Musk’s constant disregard for the emotional well-being of anybody (including himself), with Musk not knowing how to run a smooth transition to steady state or likely treating it as important, with Musk getting bored in meetings with camels and hence them feeling disrespected and neglected (camels need care and feeding too), and with the necessity to keep rolling out Superchargers that work reliably.

To me, this reads as Tesla screwing up on recognizing the necessity to effectively transition that team to steady state and starting the process 2-3 years ago, treating it seriously and managing it effectively. The mass firing and now rehiring are the symptoms of the failure, not the failure itself.

And to be transparent, an organization which is shifting to steady state, even if that’s massive steady state growth through geographical expansion, a preponderance of quality product delivery, and a skunk works for strategic spongeworks, needs a CEO who knows how to run a steady state organization with an innovation team, not a startup CEO. The Supercharger kerfuffle should be a clear wakeup call to Tesla’s Board that the organization is in a transition that needs a new quarterback, even if the last four years of X PR catastrophes, the Boring Company failure, and the Hyperloop nonsense didn’t register sufficiently.

Musk could be that CEO if he was still able to learn new tricks. But as I noted in a lengthy piece late last year, there’s a slippery path that billionaires and oligarchs have great trouble avoiding, one where they end up surrounded by people who tell them what they want to hear instead of what they need to hear. Musk shows all the signs of having entered late-stage oligarch land, where hubris, Dunning Kruger, confirmation bias, and King Canute’s courtiers live.

Have a tip for CleanTechnica? Want to advertise? Want to suggest a guest for our CleanTech Talk podcast? Contact us here.

Latest CleanTechnica.TV Video

CleanTechnica uses affiliate links. See our policy here.