Where there’s fire, there’s smoke.

And there is definitely smoke in the U.S. banking system.

The mainstream consensus is that the Federal Reserve successfully raised interest rates, slayed the inflation monster, and did it without breaking anything in the economy. Most people seem convinced the central bank will continue guiding the economy to a soft landing, and soon, it can go back to delivering the easy money the economy depends on.

But we keep getting a whiff of smoke.

On Wednesday, regional bank stocks sold off hard when New York Community Bancorp posted a $185 million loss on its most recent earnings statement after putting aside cash to cover two soured loans on a cooperative and an office. The statement revealed increased stress in its commercial real estate portfolio.

New York Community Bancorp shares plunged 37.6 percent on Wednesday and fell another 11.1 percent on Thursday dragging the rest of the regional banking sector down with it. The KBW Regional Banking Index fell 2.3 percent Thursday, following its biggest single-day decline since the collapse of Signature Bank last March.

Reuters called it “a warning for investors that had grown inured to the sector’s sensitivity to high Federal Reserve interest rates nearly a year after two banks failed.”

Open-mouth operations during the Federal Reserve’s January meeting added fuel to the fire. Fed Chair Jerome Powell effectively took any hope for a March rate cut off the table.

As Reuters put it, “While NYCB’s confluence of problems are unique to its balance sheet, elements of its earnings underscored regional lenders’ ongoing sensitivity to high Fed rates which continue to squeeze commercial real estate (CRE) portfolios and lending margins, investors said.”

Lazard CEO Peter Orszag told Reuters that the issues and NYCB underscore broader problems in the banking sector.

There still is an underlying business model problem that is affecting a lot of regional and community banks in a higher rate environment.

That underlying business model problem is directly tied to high-interest rates and a sagging bond market that has decimated the portfolios of many small and regional banks. Simmering troubles in the commercial real estate market compound the problem.

The CRE sector faces the triple whammy of falling prices, falling demand, and rising interest rates. That’s a big problem for small and midsized regional banks that hold a significant share of commercial real estate debt. They carry more than 4.4 times the exposure to CRE loans than major “too big to fail” banks. According to an analysis by Citigroup, regional and local banks hold 70 percent of all commercial real estate loans. And according to a report by a Goldman Sachs economist, banks with less than $250 billion in assets hold more than 80 percent of commercial real estate loans.

Ironically, the FOMC removed language declaring the “banking system is sound and resilient” from its official statement on Wednesday.

I’ve been pointing out the underlying problems in the banking system for months, and I’ve argued that the financial crisis that kicked off last March continues to bubble under the surface. I’ve smelled smoke for a long time.

Now it seems the mainstream has noticed.

This was inevitable the moment the Federal Reserve started hiking interest rates. This bubble economy runs on easy money – artificially low interest rates, debt, and money creation. Take it away, things eventually break.

The Federal Reserve Doused the Flames; Failed to Put Out the Fire

The fire broke out last March when Silicon Valley Bank went under, quickly followed by the demise of fellow regionals Signature Bank and First Republic.

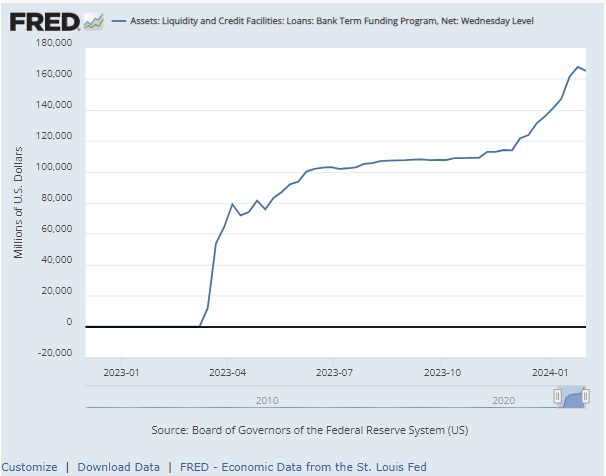

The Federal Reserve sprang into action, setting up a bailout program known as the Bank Term Funding Program (BTFP). The program is a sweetheart deal for banks struggling to raise short-term capital.

Through this lending facility, banks, savings associations, credit unions, and other eligible depository institutions can take out short-term loans (up to one year) using U.S. Treasuries, agency debt and mortgage-backed securities, and other qualifying assets as collateral.

That’s where the sweetheart deal comes in. Instead of valuing these collateral assets at their market value, banks can borrow against them “at par” (Face value).

Since the Fed started raising interest rates, bond prices have dropped precipitously. The amount banks can borrow based on the current market value of their bond portfolios is much less than what they can borrow when the Fed values the collateral at par. In other words, the BTFP allows banks to borrow more than they otherwise could due to the big drop in bond prices over the last year-plus.

According to a Federal Reserve statement, “The BTFP will be an additional source of liquidity against high-quality securities, eliminating an institution’s need to quickly sell those securities in times of stress.”

The BTF doused the flames, but the embers continued to simmer inside the walls. In effect, the Fed papered over the problem and then told us everything was fine.

Nearly a year later, banks continue to take advantage of that sweetheart deal.

Between Nov. 19 and Jan. 24, the amount of outstanding loans in the BTFP increased by $53.9 billion.

As of Jan. 31, the balance in the BTFP stood at just over $165.2 billion. That was a slight decrease from the peak of $167.8 billion the previous week.

The fact that banks are still tapping into this bailout program nearly a year later is another puff of smoke.

Unfortunately for the banking system, the BTFP goes away in March unless the Fed decides to extend the program.

As the saying goes, things happen slowly and then all at once. The financial system and economy could continue to smolder along into the foreseeable future, or it could burst into a conflagration tomorrow. But the smoke is there.

And so is the fire.

********