Sign up for daily news updates from CleanTechnica on email. Or follow us on Google News!

In the annals of zero emission vehicle startups there are innumerable failures. The Canadian/UK firm First Hydrogen is inevitably going to be one of them. I write this article not to hasten their demise, but to ask a set of questions about how this type of thing gets funded, gets press, gets the appearance of traction and the like. Think of it as an aid to investors in other inevitable failures.

The firm came to my attention in the summer of 2023, when a big announcement was made that they had secured land in Shawinigan, Quebec, birthplace of former Canadian Prime Minister Jean Chretien and location of a remarkable string of fires that consumed hotels and inns, eight of the fifteen established in the town over its history. Remarkably, only one person, an associate of Chretien’s whose inn had received a C$615,000 loan from the government while Chretien was PM, was ever charged with arson and he was acquitted as the evidence was entirely circumstantial.

Shawinigan is a moderately picturesque town of 49,600 located halfway between Montreal and Quebec City on the Saint-Maurice River. Formerly a fairly vital industrial hub due to the hydroelectric dam, with pulp and paper, chemical, textile and aluminum industries taking advantage of the energy, it’s been in decline since the 1950s. Its growth industry is retirement homes, with a full third of its population over 65 and its average age eight to nine years higher than Canadian cities like Vancouver, Toronto and Montreal, and its population is slowly shrinking.

But it still has that 200 MW hydro dam that’s been in operation since 1910, meaning its carbon debt is long paid off. When I heard that a firm was going to be building an electrolysis facility there with their own money, I had my doubts but saw no evidence of any particular governmental largesse, so shrugged and moved on. As a place to build a green hydrogen facility, there are worse choices. Quebec needs fertilizer too, although fertilizer giant doesn’t make any fertilizer in the province right now, instead importing it via a terminal on the St. Lawrence. Quebec is blessed with lots of green electricity but no fossil fuel reserves to speak of, so the location preferences for ammonia-based fertilizer have flipped in its favor so perhaps something will happen there.

A bit about First Hydrogen

What I hadn’t realized was that First Hydrogen was actually a hydrogen vehicle wannabe. They finally built a prototype with a lot of professional help from vehicle engineering and test firm AVL with, of course, a Ballard fuel cell in the mix. Engineering firm Arup was also engaged. As I noted in a recent article, Ballard has been going from failure to failure for 44 years and has lost $1.3 billion of other people’s money since 2000. AVL, per its history, has been quite happy to take fuel cell vehicle wannabe’s money for years now, and I’m sure Arup doesn’t mind the revenue either.

A bit of history on First Hydrogen. It was apparently founded in Vancouver in 2007, so it’s a 16 year old organization, although there’s precious little indication it did much until recently. A Vancouver real estate and construction mogul, Balraj Mann, who appears to have started or owns about 20 firms which do building related things, founded First Hydrogen and is the Chair and CEO.

That Vancouver location means that he is in the weird BC bubble that continues to think hydrogen for energy is an amazing thing, but as Ballard’s litany of abandoned trials and partnerships with OEMS like Audi and Ford shows, that’s because all of the starts are publicized as heavily as possible, but the failures are swept under a very lumpy rug in Ballard’s headquarters.

BC has a little ecosystem of hydrogen going on, with AVL having a fuel cell division here, Greenlight Innovations building and selling fuel cell test benches to firms that foolishly get into the business including Hyundai which was their biggest customer last time I talked to the Managing Director and a few others.

Clearly the US Inflation Reduction Act leaning into hydrogen and Canada unlocking purse strings in a matching action unlocked more foolish money as in April of 2022, First Hydrogen managed to get a trivial amount of money finally, C$6 million. This year they managed to scrape another $2.9 million out of unnamed investors. In the road vehicle startup space, $9 million is chump change, orders of magnitude off of the required capital. And for establishing a hydrogen manufacturing concern?

Manufacturing green hydrogen in Shawinigan?

Let’s look at the fiscals of the purported hydrogen manufacturing facility first. They received the land from the city of Shawinigan. As the quick look at it above showed, it’s a shrinking, rural town desperate for investment. The odds that they received the land for free or close to it are high. Good enough. There is exactly no skilled workforce to speak of in the town, so they’ll have to import, well, everybody, but it’s a nice enough town and only a couple of hours’ drive from a great city.

They are asserting a 35 MW electrolysis facility. Let’s assume that they go with the cheaper alkaline electrolyzer, which per the IEA is running around US$400 per kW of capacity excluding balance of plant, that’s US$14 million or C$18.6 just for the electrolyzers, more than double their entire capitalization. The balance of plant of roughly another 27 components is important too, and includes an actual building, so call it double that easily.

What about electricity costs? Well, there’s a reason to build green hydrogen facilities in Quebec and that’s because industrial rates are advantageous and the electricity is green. But cheap doesn’t mean free. They would be getting electricity under Hydro Quebec’s Rate L industrial category at C$0.03503 per kWh and $13.779 per peak kW. That latter means the 35 MW electrolyzer plus likely another 5 MW of balance of plant draw for 40 MW would cost them a committed C$550,000 per month, which would burn through their C$9.9 capitalization in 18 months, if they had any of it left over after building the plant, which they won’t.

Hydro Quebec likes 95% utilization power draws, otherwise they start charging serious peaking surcharges, so let’s assume that First Hydrogen’s 40 MW total draw is at that utilization rate. That turns into a million a month in energy costs. Water in Quebec is dirt cheap even with the new rates of $35 per million liters, so it’s a rounding error of costs.

In an hour at full utilization they would manufacture about 727 kilograms of hydrogen. Just the electricity costs turn into C$2.96 per kilogram. The capital cost, amortized over the roughly 10 years of the electrolyzers, adds another $0.58 per kilogram, making it C$3.55 or US$2.70. This is, by the way, the absolute best cost case that is likely, and things like heavily inflated executive compensation — see below — will make the cost per kilogram go up too.

That’s actually a really good cost for manufacturing green hydrogen, the best economics I’ve seen anywhere (making me suspicious I missed something). At only about three times US per kilogram costs from steam reformation of fossil methane, it’s much better than costs pretty much anywhere else will be. This part of First Hydrogen’s business case is actually reasonable, even if they are short tens of millions of dollars to build it and $550,000 per month for just the electricity to run it.

Add 10% financing and 10% profits as notional numbers and that’s about C$4.30 or US$3.24 per kilogram, undelivered.

If only there were anything in Shawinigan to consume the hydrogen, because storing and moving hydrogen around is very expensive. There isn’t. Remember, there are no fertilizer plants in Quebec, never mind in Shawinigan. There are two refineries — remember that the single biggest consumer of hydrogen on the plant is the oil industry to hydrotreat, hydrocrack and desulfurize crude oil — but they are in the suburbs of Quebec City and Montreal, 90 to 120 minutes driving down the highway way.

Delivering hydrogen by tanker truck is expensive. Even with black or gray hydrogen at $1 to $2 per kg manufacturing costs, when delivered by truck hydrogen costs in the range of US$11 or $15 CAD. Assuming the same pre-profit gross up, that puts delivered hydrogen by truck at around C$17 to $18 at the refineries. I suspect that they won’t be buying it at those prices, as they will prefer to have the federal and Quebec governments pay them to make blue hydrogen and store the carbon, turning a problem into an opportunity to suck more oil and gas subsidies.

Is this unusual? No. Black or gray hydrogen dispensed in California and Europe costs between US$17 and $35 per kilogram at the pump. In Canada, HTEC runs the hydrogen refueling stations. It’s another dead end BC company in the little bubble here. At its BC stations, the locally electrolyzed hydrogen using BC’s cheap and low carbon electricity costs C$14.70 per kilogram or US$11, making it the cheapest pumped hydrogen I’m aware of, and still vastly more expensive per kilometer than just using electricity more directly via batteries.

Basically, there’s nothing anywhere near Shawinigan that needs green hydrogen and delivering it anywhere makes it very expensive. That’s why 85% of hydrogen is manufactured at the point where it is consumed, and the vast majority of the rest is piped relatively short distances to high volume consumers from steam reformation plants, as is the case in Edmonton and in Germany.

Building hydrogen fuel cell delivery trucks in Shawinigan?

And so we get to the second half of First Hydrogen’s failure in motion, creating demand. With the money that they won’t have after building a green hydrogen manufacturing facility, they are going to build a fuel cell delivery van assembly factory in Shawinigan, one capable of delivering 25,000 vehicles a year. Just establishing a light electric truck facility — something potentially sensible to do — can cost US$11 million or C$15 million, according to one internet source, once again greater than their entire current capitalization.

Their prototype van is a 3.5 metric ton van, a standard size for package and light deliveries. This class of vehicle averages about 60 kilometers a day of driving per US statistics, assuming six days of operation. That’s a bell curve of course, so some undoubtedly drive much further, but extreme range is likely to be 400 km, which is what Ikea in Austria requires for some routes apparently.

They aren’t 24/7 vehicles, so depot charging of electric versions is trivial. They aren’t semi trucks, so electric versions can recharge at any fast charger, and there are hundreds of fast chargers dotted around the place already. There are already 400 km range electric vehicles available in this class, for example, BrightDrop with its US$85,000 price tag. That firm is a subsidiary of GM, which actually knows how to manufacture trucks and has strong relationships with automotive component manufacturers like Magna.

I brought up Ikea earlier for a reason. They acquired five hydrogen fuel cell trucks from Quantron, because that firm was incompetent to make a 400 km battery electric van it seems. The government of Austria had to fund the acquisition because the entire package including the refueling station cost €4.8 million, or C$7 million. That’s C$1.4 million per truck.

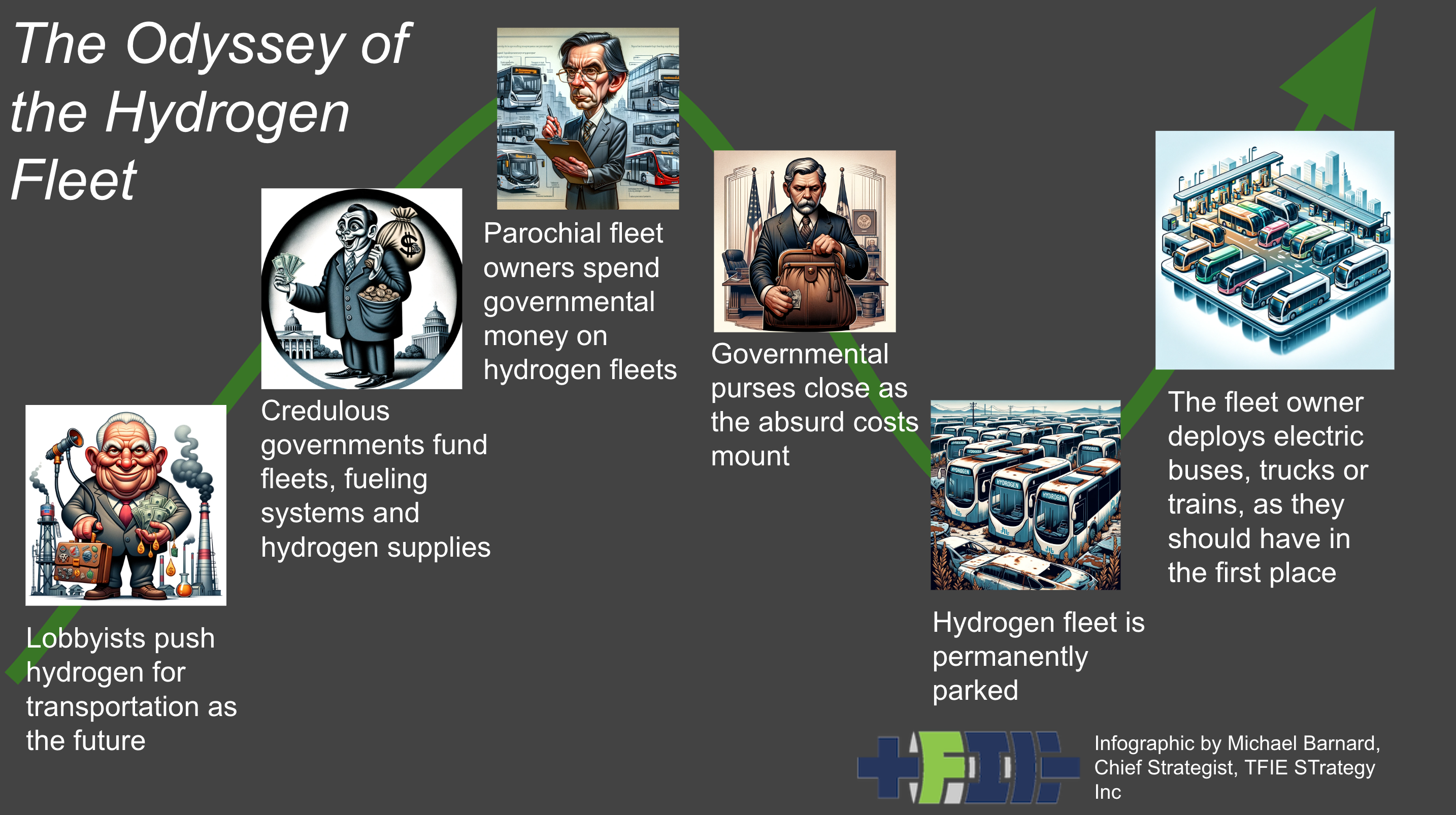

That’s absurdly high, isn’t it? But a million US of governmental money per truck or bus is about average for hydrogen trials, per my assessment of the ongoing stagings of the Odyssey of the Hydrogen Fleet tragicomedy.

Much of that is for a hydrogen refueling station. The only one that currently exists in Quebec, on the outskirts of Quebec City, cost C$5.2 million, is able to refuel a single car at a time and was installed to fuel 50 Toyota Mirais the Quebec government leased four years ago as a light vehicle experiment. That experiment ended late this year with the cars returned to Toyota and no information forthcoming. The refueling station is still there, attached to an Esso station, but there are only 20 registered hydrogen vehicles left in all of the province, so it’s barely used.

At least there’s one in a reasonably sized urban area serving a population of 737,000 people. So there’s that. The next nearest multimillion dollar stations are, of course, in British Columbia, which has five of them serving that province’s 5 million citizens. Mostly are sitting idle most of the time, as there are only 195 fuel cell vehicles registered in the province and many are second cars for people who work in the hydrogen industry. Ballard convinced a bunch of its employees to lease Toyota Mirais a couple of years ago and the general manager of Greenlight Innovations leased one as well. Yes, after decades of pushing the hydrogen transportation rope uphill with lots of provincial and federal money, there are fewer than 200 fuel cell vehicles in the province. Meanwhile, there are about 110,000 battery electric vehicles already, and rising quickly.

What other contextual data is worth considering when assessing First Hydrogen’s hyperbolic claim of building 25,000 fuel cell delivery vans a year?

Well, Ballard, after 44 years remember, states that there are only 3,700 fuel cell trucks and buses in operation with its technology inside. Also globally, there are only 40,000 fuel cell fork lifts in operation, about 3% of the battery electric forklifts purchased globally in 2021 alone. Most of those had US Department of energy funding for the very expensive refueling infrastructure and initial purchases, and have just persisted in buying more as they expanded. The demand for fuel cell vehicles is staggeringly absent, even in hotbeds of hydrogen delusions like BC.

How much hydrogen will a 3.5 ton van require? After all, that’s First Hydrogen’s demand growth strategy, so they must need a lot. Now let’s turn to the Rivus white paper that First Hydrogen carefully cherry picks quotes from to make it sound like the test was a roaring success.

How did their prototype fare in testing?

Rivus is, or perhaps was, a good company to test a hydrogen van. It’s on the UK’s biggest fleet management firms with garages across the UK, managing fleets for a lot of the biggest operators in the country. It has the toughest use cases among its portfolio, including deep outliers over 600 kilometers of daily driving. As a reminder, the average is 60 kilometers for this class of vehicle. The Ikea case study is also worth looking at as they have 56 battery electric delivery vehicles and only acquired five fuel cell vehicles for those longer routes (and remember, battery electric vans completely capable of covering the same distance are available, so this wasn’t a rational choice, just free money from the government).

When I say was a good company, shortly after Rivus completed the four week trial and returned the sole working prototype to First Hydrogen, the firm closed half of its facilities in the country.

Regardless, Rivus picked three routes that were serviced by gasoline or diesel trucks. Over the four weeks, the van operated for 47 hours, covering 1,200 kilometers. That’s an average of 25 kilometers per hour and 54 kilometers per working day, by the way. It’s deeply unclear if any of these routes couldn’t be handled trivially easily by lower range battery electric vehicles, they would just need to charge up at the depot at night instead of going to a gas station once a week.

The fuel cell operated only 40% of the time, and that was only because First Hydrogen specced a smaller, weaker battery than would go in a normal battery electric vehicle. Virtually all fuel cell vehicles are actually battery electric vehicles with complex and failure prone hydrogen tanks and fuel cells as range extenders, and the First Hydrogen design is no different.

They consumed 3.3 kilograms of hydrogen for every 100 km of driving. How does that compare to the output of the proposed Shawinigan plant? Well, at the rate of 726 kg per hour, that’s 22,000 kilometers of driving, which is to say as more than a single average delivery van drives in a year. They’d need to have over 9,000 delivery vans running to consume the hydrogen of the Shawinigan plant.

Anything else? Oh yes, refueling problems. The Rivus facility was right next to one of the grand total of 15 hydrogen refueling stations in all of the UK. One of the things that hydrogen transportation types claim is an advantage of hydrogen is fast refueling, just like a gas station, as if recharging in a depot overnight wasn’t much cheaper and easier for vehicles which average 60 kilometers per day.

But when you pick at the ‘fast refueling’ claim, it falls apart, as Rivus discovered. Hydrogen refueling facilities only deliver a few kilograms before massive pumps spool up and repressurize the hydrogen back to 700 atmospheres. That’s fine for Toyota’s 5 kg hydrogen tanks, but with the 10.3 kg tanks, refueling took three times as long. This is even worse for heavy goods vehicles by the way, which might need 100 kg of hydrogen for their longest ranges. The US NREL has managed, in a carefully designed facility, to manage pumping of hydrogen at 700 atmospheres as quickly as diesel, but at commercial pumps 100 kg would take 60 to 90 minutes. There’s no indication that NREL’s massive test rig will turn into a commercially viable pumping station when the single hose pumping stations that are currently in use cost millions.

Anything else? Yeah, it was too expensive to operate, almost twice as much as a battery electric vehicle.

“Rivus analysis found that – at the moment – the First Hydrogen vehicle struggles with cost comparisons to BEVs and diesel vans. At current hydrogen prices of £9.23 per kilo, the vehicle cost 31p per mile to fuel. At 40p per kWh, a fully-electric LCV would cost 18ppm, while a diesel would cost 22ppm if the pump price was £1.46 per litre.”

That’s clearly gray hydrogen being pumped, by the way, as at the £0.40 per kWh noted, a kilogram of hydrogen would cost £22 just for the electricity. Always ask where the hydrogen is really coming from because it’s frequently mind boggling. For example, the Whistler, BC hydrogen bus trials of 2010 to 2014 trucked it from Quebec, a diesel-powered round trip of roughly 9,000 kilometers for a load sufficient to power a bus for about 10,000 kilometers.

Of course, the same electricity would power 27,000 battery electric delivery vans at a fraction of the cost per kilometer and a much lower cost per vehicle. There’s a reason why there are only 3,700 buses and trucks globally operating with Ballard fuel cells in them, and fewer than 10,000 fuel cell vehicles in China compared to around 1.2 or 1.3 million battery electric buses or trucks in the country.

First Hydrogen, of course, claims that the results were amazingly positive and mention none of the major downsides at all. One of the few men on the Board of Directors without the CEO title, Chief Commercial Office Allan Rushforth, claims hydrogen is going to get cheaper, which as this assessment shows is nonsense. He also claims that cold weather testing will really highlight the strengths of their van, ignoring the reality that fuel cell vehicles create water that freezes and disables them unless carefully managed, something that happened with the defunct Whistler, BC bus fleet frequently.

Other red flags about First Hydrogen

Are there any other red flags about First Hydrogen that should be mentioned? Well, how about that per their website and LinkedIn, they have only 16 people associated with the firm, and three of them, men of course, have the title of Chief Executive Officer. To put this in context, there are exactly seven Fortune 500 companies that have more than one person with that title, and they each have two co-CEOs. Any other doubling up? Yes, in addition to the Chair, there’s an Executive Chair. This 16 person firm has four people with CxO titles, a vastly top heavy executive structure and related compensation.

Public documents indicate that the Chair, Balraj Mann, is getting about $480,000 a year, and remember that there are two men with the CEO title and presumably high salaries as well. Then there are the non-executive Board members who are being compensated handsomely for their time one assumes. Remember also that Mann owns another 20 or so firms and is listed as CEO of at least four of the them. A fractional CEO of a company that has zero revenue and approaching zero likelihood of any revenue is worth almost half a million per year?

It’s fairly obvious why I started this piece with the note that First Hydrogen was inevitably going to fail, and it should be clear why now. They have nowhere near the money to do what they say they are going to do, what they say they are going to do makes no sense, and their projections about scale of the electrolysis facility and the number of vehicles that they are going to manufacture makes no sense. Their partner Ballard has lost an average of $55 million a year since 2000 because virtually no one is buying fuel cell vehicles unless some government ponies up a million or more per truck or bus. As soon as the government stops funding the hydrogen, every trial ends.

The red flags are huge and flapping in a gale force wind with this firm.

Yet First Hydrogen raised almost C$9 million and have a bunch of governmental luminaries showing up at their announcement in Shawinigan and apparently believing that they are going to do this. Is that because it’s hard to find out anything I’ve listed above? No, it’s all public information.

Is that because the governmental luminaries and Mayor of Shawinigan know something I don’t? No, that’s not likely either. What’s much more likely is that they have no clue about any of this, never did the slightest bit of work with Google and spreadsheet, didn’t ask any rational transportation analyst to review it, didn’t have any flunkies run Google or a spreadsheet, and basically just bought what First Hydrogen was selling. After all, the firm has a former Ballard executive and a former Ford executive on the Board, as well as a Quebec public affairs director who is clearly good at creating press and getting connections in that province.

Remarkably, this firm managed to go public in 2020. And yes, despite having nothing but seed funding and before they had a single prototype vehicle, they managed to achieve a stock price of almost C$5.15 per share in September of 2022 and a peak market capitalization of a quarter of a billion dollars, albeit Canadian ones.

Clearly the prototype vehicle they had in testing in the early summer of 2023, the October 30th, 2023 track day for fleet owners and press didn’t impress retail investors, as their stock price has dropped by two-thirds, back to its still far overvalued current level. Their second raise being half of their first raise likely didn’t help.

Caveat emptor and don’t spend tax dollars on it

It’s entirely possible that everyone involved is completely sincere, despite their claims and business plan being complete and easily dismissed nonsense. After all, there is the ongoing bubble of hydrogen for energy delusion that is continuing and Mann is a Vancouver player, where the hydrogen for energy bubble continues to be periodically reinflated, with multiple firms distorting the the local economy. As my local contacts tell me, Ballard is paying big bucks for electrochemists and chemical engineers, contributing to the past years’ massive losses.

Mann is obviously a deeply shrewd business person and has done very well for himself. Clearly he’s doing very well for himself with First Hydrogen, regardless of whether it succeeds of fails, well on his way to harvesting a million dollars out of the company. He started the firm in 2007, and then got sufficient people on board with sufficient experience to make it look credible and draw $9 million in investment so far based on tissue paper and thumb tacks. That he has no background in energy, transportation or hydrogen other than this, as well as no STEM credentials I was able to find, might mean that he actually thinks this is a reasonable company.

The former Ballard executive is, of course, well connected in the hydrogen bubble and undoubtedly is being supported in his cognitive biases strongly as a result. The UK technical director, one of the couple of STEM qualified people in the firm it seems, is an engines guy for his entire career, so strongly aligned with molecules for energy.

And I can’t tell you the number of people who have tried to make the argument that because governments are creating hydrogen for energy strategies and major firms are toying with it, that I’m clearly wrong in my empirical, factual and logical analyses and assessments.

Clearly the people who put in $9 million and the retail investors who own FYHD did zero due diligence upon the claims and business plan, even though it’s trivially easy to do. The basics of this article took 30 minutes to find, looking solely at publicly available data, although I do have a strong background in transportation repowering and the actual costs of manufacturing hydrogen.

But for governmental types in BC, Quebec and Ottawa, please don’t throw any more taxpayer money at First Hydrogen or hydrogen for energy in general. And for investors eying First Hydrogen or firms like it, caveat emptor. Your money is yours to waste however you see fit, but it could be much better used elsewhere if you actually want to have it grow and do something worthwhile.

Have a tip for CleanTechnica? Want to advertise? Want to suggest a guest for our CleanTech Talk podcast? Contact us here.

Our Latest EVObsession Video

I don’t like paywalls. You don’t like paywalls. Who likes paywalls? Here at CleanTechnica, we implemented a limited paywall for a while, but it always felt wrong — and it was always tough to decide what we should put behind there. In theory, your most exclusive and best content goes behind a paywall. But then fewer people read it!! So, we’ve decided to completely nix paywalls here at CleanTechnica. But…

Thank you!

CleanTechnica uses affiliate links. See our policy here.