Support CleanTechnica’s work through a Substack subscription or on Stripe.

Our readers wouldn’t know this, but I have a job outside CleanTechnica, working for the Colombian government as an analyst of the current conflict waged between Colombia and the various armed groups operating within our territory.

The recent impasse between Colombian President Gustavo Petro and US President Donald Trump prompted me to work on an article focused on the role I increasingly believe cleantech will play in the War on Drugs. For this, I joined efforts with my colleague and friend Fredy Figueredo, a sociologist working specifically on the matter of coca crops on formerly stolen or dispossessed lands, to whom goes a large degree of credit for the data and analysis present in this article.

A bit of context: cocaine production in Colombia in the 20th century

Since its inception in the 1970s, cocaine production has been linked with Colombia’s low intensity war, funding the paramilitary armies of private drug dealers, including the infamous Pablo Escobar.

By the 1980s, the alkaloid had also become a financial pillar for some guerrillas, in particular Colombia’s Revolutionary Armed Forces (FARC) through a mechanism called gramaje which was basically a “tax” on cocaine commercialization within their controlled areas. The control on coca-leave producing regions led to widespread wars all but unknown outside Colombia, the fiercest of which was probably the one between the MAS paramilitary group led by Gonzalo Rodríguez Gacha (a member of the Medellin Cartel and an associate of Escobar) and FARC, which ended in victory for the Marxist guerrilla over the Narco. There’s far more to these matters, but the scope of the article is different, and I feel the relationship between cocaine and violence has been presented, so we’ll leave it at that.

Despite significant efforts from the part of the Colombian government, which included the taking down of Escobar, cocaine production would keep rising through the 1990s.

The current status quo

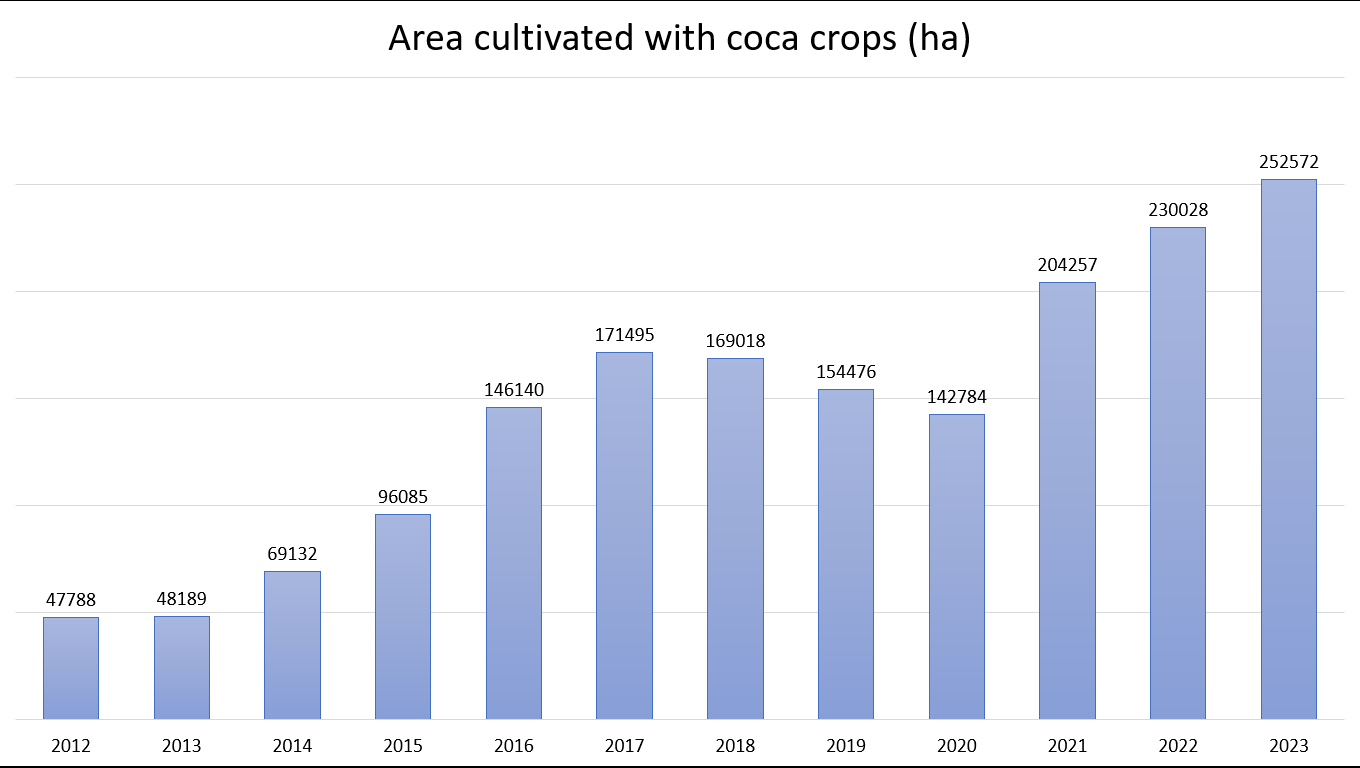

Let’s jump a couple of decades ahead. After a few years of reduction in the total area of coca crops in the country, the number started to rise again in 2013. Two reasons are normally presented as probable cause: first, the end of aerial glyphosate aspersion (which was banned due to significant risk for the communities and the destruction of legitimate food crops alongside coca crops, something extremely damaging in distant regions with no easy access to the national food market). Second and likely more important was the oil crisis and the subsequent plummeting of the Colombian peso, which suddenly doubled the narcos’s income on any given amount of cocaine exported to the US.

Together, these two factors led to a significant growth on coca-leave crop area, meaning that Colombia’s cocaine production has steadily risen through the last 12 year or so, and since productivity by area has also risen (by as much as 4 in the last couple of decades, according to some reports), this means cocaine production has reached new heights in the 2020s. This has happened despite significant efforts by the Colombian government to curb it, either by outright repression (as was done under the former president, Ivan Duque) or by negotiations and crop substitution (as is being done under current president, Gustavo Petro).

Gasoline’s link with cocaine

Some of our readers may be wondering already: that’s cool and all, but what the hell does cleantech even have to do with this?

Well, let’s work our way to it. Coca leaves are not cocaine (nor should the two be confused, as unprocessed coca leaves are a traditional staple of indigenous communities) and must undergo a chemical treatment before turning into it. A simplified version of the process goes like this: the coca leaves are mixed with some alkaline mixture to free the alkaloid, then an organic solvent is incorporated to extract it, later being precipitated with some acid solution to obtain “base paste,” which is then commercialized to larger drug-dealing organizations to be further purified. The nature of the process means that — unlike with synthetic drugs — specific chemical precursors are not needed, so there’s a large degree of variability on the specific substances used. However — and this is very important — a significant amount of chemicals, in particular organic solvents, are required.

And this is where cleantech enters the play, because the main input for cocaine production is no other than gasoline (or, alternatively, diesel).

See, according to the available data, some 75 gallons of gasoline are required to produce 1kg of cocaine. In the aggregate, it gets worse: according to UNODC, through 2023, 322 million gallons of gasoline were used to produce cocaine, whereas Colombia’s Treasury and Public Credit Ministry calculates total gasoline consumption at 2.378 billion for that same year.

Let that sink in.

A massive, a humongous 13.54% of all gasoline sold and used in Colombia is used as a chemical precursor for cocaine*. This means that cocaine production is reliant in massive amounts of this product being readily available for purchase, and that — in theory — controlling its use could bring cocaine production to a halt. Yet, as we will see in the following section, to impose such controls remains outside the capacity of the Colombian government, for now.

*Recent official reports put that number at 4–12%. Our calculations run just a bit higher than that.

Puerto Asís, Putumayo. A case study

Located in the frontier with Ecuador, in the coca-producing department of Putumayo (which, alongside Nariño, accounts for 64% of the national area of coca crops), Puerto Asís is the municipality with the highest amount of coca crops by area in the department, and as of the latest UNODC report (2023), it’s on the national top 10. Puerto Asís is in Colombia’s Amazon Region, meaning it depends on fluvial connections for commerce, services, and transportation. Also relevant here, Puerto Asís is far from wealthy, having poverty levels of 44.1%, something sadly common in coca-producing regions. According to UNODC, around ¾ of coca producers are also involved in the transformation to base paste: this process, roughly described above, requires several inputs, of which gasoline and cement account for 90%, and of which gasoline is the most expensive one.

In recent years, Puerto Asís’ location, poverty levels, lack of opportunities, and state absence have promoted the rapid growth of coca crops and the subsequent growth on base-paste production. An interesting calculation here can be done when comparing this municipality’s gasoline consumption, per capita, with a regular (non-coca-producing) city in central Colombia, such as Madrid, a small city outside Bogota:

- Puerto Asís. Population: 73,141 inhabitants. Gasoline consumption: 4,887,245 gallons in 2023.

- Madrid. Population: 136,174 inhabitants. Gasoline consumption: 4,777,305 gallons in 2023.

We get 35 gallons/inhabitant in Madrid and 66.8 gallons/inhabitant in Puerto Asis. And keep in mind that Madrid is a city with a massively wealthier population of which a much higher proportion owns a personal vehicle. Madrid is also home to a large industry of flower production which also uses gasoline and diesel in large amounts for transportation. So, a large degree of the difference with Puerto Asís is likely due to coca processing.

Cocaine’s logistical bottleneck

This massive consumption, happening in very sparsely populated regions, is only possible thanks to the omnipresence of fossil fuels (and oil in particular) in all aspects of rural life, from transport to farm work (most machinery having an internal combustion engine) and even electricity generation. The discrepancies have been noted by governments for years, as gasoline consumption in rural regions sometimes even surpasses urban consumption, despite the population being far lower. As a matter of fact, one of the main arguments of current president Gustavo Petro for the finalization of the de-facto subsidy for gasoline was that it was basically “subsidizing narcos.”

Yet, attacking this part of the supply chain remains extremely difficult. Colombia’s government cannot decisively cut the availability of organic solvents (I mean, of gasoline and diesel) to these rural regions without destroying legitimate economic activities, decimating food production, and isolating them of the rest of the country … even though they have tried, most notably during the Perseus Operation (Oct. 2024) to regain control over the Micay Canyon. Back then, the Colombian Army dismantled gasoline stations built in places with few to no cars, which, presumably, were built solely to provide inputs for cocaine production.

It goes further. Well aware of the key role oil plays in cocaine processing, in August 2024, Colombia’s government required fuel stations in the 10 highest coca-producing departments in the country to operate with an official permit, which would require a certification of non-drug traffic expedited by the Ministry of Justice. This well-intentioned effort, however, involves significant bureaucratic hurdles regularly evaded by local actors, which in practice translate to 855 fuel stations not complying with the regulation (out of 2,900 total in the 10 departments).

What this means is that controlling gasoline distribution could be a viable strategy in specific areas, but corruption, lack of institutional presence, and outright threats by armed actors make it extremely hard for this strategy to scale. To win, to truly choke cocaine’s biggest logistics bottleneck, fuel use needs to end.

And it’s here that cleantech enters the play.

A dagger to cocaine’s production hearth

Allow me to present a dream. Allow me to think of a world in which not gasoline motorcycles but electric ones drive people to their destinations; where electric trucks and pickup trucks move their produce around; where electric scythes are used to clean the fields; where solar panels replace generators to keep the lights on.

We could go further. We could think of cheap e-bikes and e-cargo bikes allowing those too poor for a motorcycle to have a reliable, affordable means of transportation. We can imagine subsidized solar stations and even solar microgrids* providing affordable — or even free — electricity at daytime for the people to charge their vehicles, whereas they need to pay a significant amount nowadays for expensive gasoline that must be transported through the mountains before being sold. We can even dream of electric delivery drones eventually breaking the isolation that brought coca crops into these regions in the first place, allowing for the easy export of local produce to large cities.

*Microgrids are already being built under the “Energy Communities” program, BTW.

But I digress.

In this Dream World, drug dealers and Narco Armies would be very hard pressed to find a way to move around over 400,000 barrels of gasoline every month without anybody noticing. In this world, the Colombian Army could focus on choking cocaine’s main logistics bottleneck while leaving farmers alone, by simply focusing on locating and seizing any large amount of gasoline, diesel, or kerosene entering these regions. Without access to a massive amount of organic solvent readily available in the local markets, the economies of cocaine could be decisively broken, or, at least, severely hurt.

More importantly, this strategy would not require a national intervention all at the same time. The government could focus on some regions first, attacking smaller nodes of production before entering larger, more complex regions. Access to affordable, reliable energy could prop up local economies that are also limited in their productivity because fossil fuels are extremely expensive when you’re a poor farmer or peasant in economically underdeveloped regions. And the technological shift would benefit first those who need it the most, whereas the current beneficiaries in the region have been urban dwellers who tend to be wealthier to begin with.

Sure, I know it’s not a safe bet. Even if the local market is controlled, gasoline can be smuggled from foreign borders, and the narcos have shown a lot of willingness to learn how to adapt. In some regions, particularly the Department of North Santander in the frontier with Venezuela, gasoline is replaced with crude oil illegally extracted from pipelines and crudely refined in artisanal labs, so additional limitations on oil production would be required.

But in these dire circumstances, I believe it is a good bet, perhaps the best one we’ve had so far.

Sign up for CleanTechnica’s Weekly Substack for Zach and Scott’s in-depth analyses and high level summaries, sign up for our daily newsletter, and follow us on Google News!

Have a tip for CleanTechnica? Want to advertise? Want to suggest a guest for our CleanTech Talk podcast? Contact us here.

Sign up for our daily newsletter for 15 new cleantech stories a day. Or sign up for our weekly one on top stories of the week if daily is too frequent.

CleanTechnica uses affiliate links. See our policy here.

CleanTechnica’s Comment Policy