Support CleanTechnica’s work through a Substack subscription or on Stripe.

Global hydrogen vehicle sales have fallen sharply again in 2025. Passenger and commercial markets that were once seen as the proving grounds for fuel-cell technology are shrinking fast. According to SNE Research, fewer than 9,000 hydrogen vehicles were sold worldwide in the first nine months of the year, down from nearly 10,000 in the same period of 2024. China, which had anchored the commercial market with buses and trucks, saw its hydrogen vehicle sales collapse by 45%, from more than 5,000 to fewer than 3,000. The global total now looks like the remnant of a fading technology class rather than a growing one.

Amid that contraction, South Korea stands out as the only country where hydrogen car sales have increased. Hyundai’s updated Nexo, released in June 2025, accounted for more than half of all FCEVs sold worldwide this year. Virtually all of them were sold in Korea. The numbers sound impressive until they are set beside the broader market. Just under 3,500 Nexos were sold in South Korea during the first nine months of 2025, while about 120,000 battery-electric vehicles were registered in the same period. The Nexo’s rise is not evidence of market preference or innovation. It is the predictable result of a subsidy architecture designed to simulate demand.

The Nexo’s retail price tells the story. Hyundai’s base price for the new model is about $53,000. After subsidies from national and local governments, buyers pay between $26,000 and $33,000, roughly half the sticker price. The national government contributes about $16,000 per car and local programs add another $8,000 to $12,000. By comparison, the maximum central government subsidy for a battery-electric vehicle is roughly $4,100, with local support adding another few thousand at most. A Korean consumer can buy an electric car with a modest subsidy or a hydrogen car with one six times larger. The outcome is predictable. The incentives are strong enough to distort the appearance of demand and hide the underlying economics.

Hydrogen fuel is also subsidized. Hyundai itself offers up to $1,700 in prepaid hydrogen refuelling credit for Nexo buyers through its “Next Easy Start” program. Retail hydrogen costs roughly $7.30 per kilogram, but the government offsets a large part of the difference between that and the true cost of production and distribution. Hydrogen station operators purchase fuel at below-market rates, and in many cases receive direct operating subsidies to cover electricity, compression, and maintenance. Even with that support, the economics are poor. Each station dispenses on average about 100 kilograms per day, well below the 300 kilograms required for breakeven. At current retail prices, a typical site might bring in $250,000 to $300,000 in annual revenue. Operating costs alone exceed that, before any amortization of the $1.5–3 million capital cost of building the station. Without subsidies, every hydrogen refuelling site would lose money.

The scale imbalance between hydrogen infrastructure and electric vehicle charging is stark. South Korea has about 231 hydrogen refuelling stations operating in 2025. It has more than 250,000 electric vehicle charging points, including over 20,000 fast chargers. Even with generous government support, hydrogen networks remain a fraction of what has been built for electricity, and they serve a market that is hundreds of times smaller. The idea that the two infrastructures are comparable is untenable. The hydrogen system exists because of public spending, not public use.

The persistence of this approach reflects a deeper policy error. South Korea’s industrial strategy has treated hydrogen as an alternative path to energy independence and a way to build a domestic industry that is not dependent on Chinese battery supply chains. Hyundai and its subsidiaries have invested heavily in fuel-cell production, hydrogen buses, and electrolyzers. The national government has reinforced that investment with a full supply chain strategy, aiming to make hydrogen a pillar of future exports. The flaw is that the economics of hydrogen for transportation do not work anywhere, and South Korea’s costs are no exception. Producing, compressing, transporting, and dispensing hydrogen consumes far more electricity than using the same power directly in batteries. That physical disadvantage cannot be legislated away. No amount of industrial policy can overcome the inefficiency of turning renewable electricity into hydrogen and then back into electricity in a car. The longer Korea maintains its commitment to hydrogen mobility, the more stranded its investments will become.

Globally, the pattern is clear. Passenger hydrogen cars have failed to scale, and commercial fleets are abandoning the technology. China’s sharp drop in hydrogen truck and bus sales is the most visible sign of that shift. Even with substantial subsidies and local content rules, Chinese operators are walking away from hydrogen vehicles because the fuel remains too expensive and the logistics too fragile, regardless of a recent odd hydrogen vehicle target that ignores the on-the-ground reality in the country. Outside of South Korea, including in hydrogen-mad Japan, the number of hydrogen refueling stations is dropping as operators realize that no market is coming for them to serve.

The idea that hydrogen refuelling station operators could pivot to serving heavy vehicles is no longer credible. Global commercial hydrogen fleets are contracting, not expanding, and the price of green hydrogen remains far above diesel on an energy-equivalent basis. In South Korea, where average throughput is already one-third of what is required for profitability, there is no path to sustainability in a shrinking global market. Operators cannot make up the shortfall with buses and trucks that are not being built.

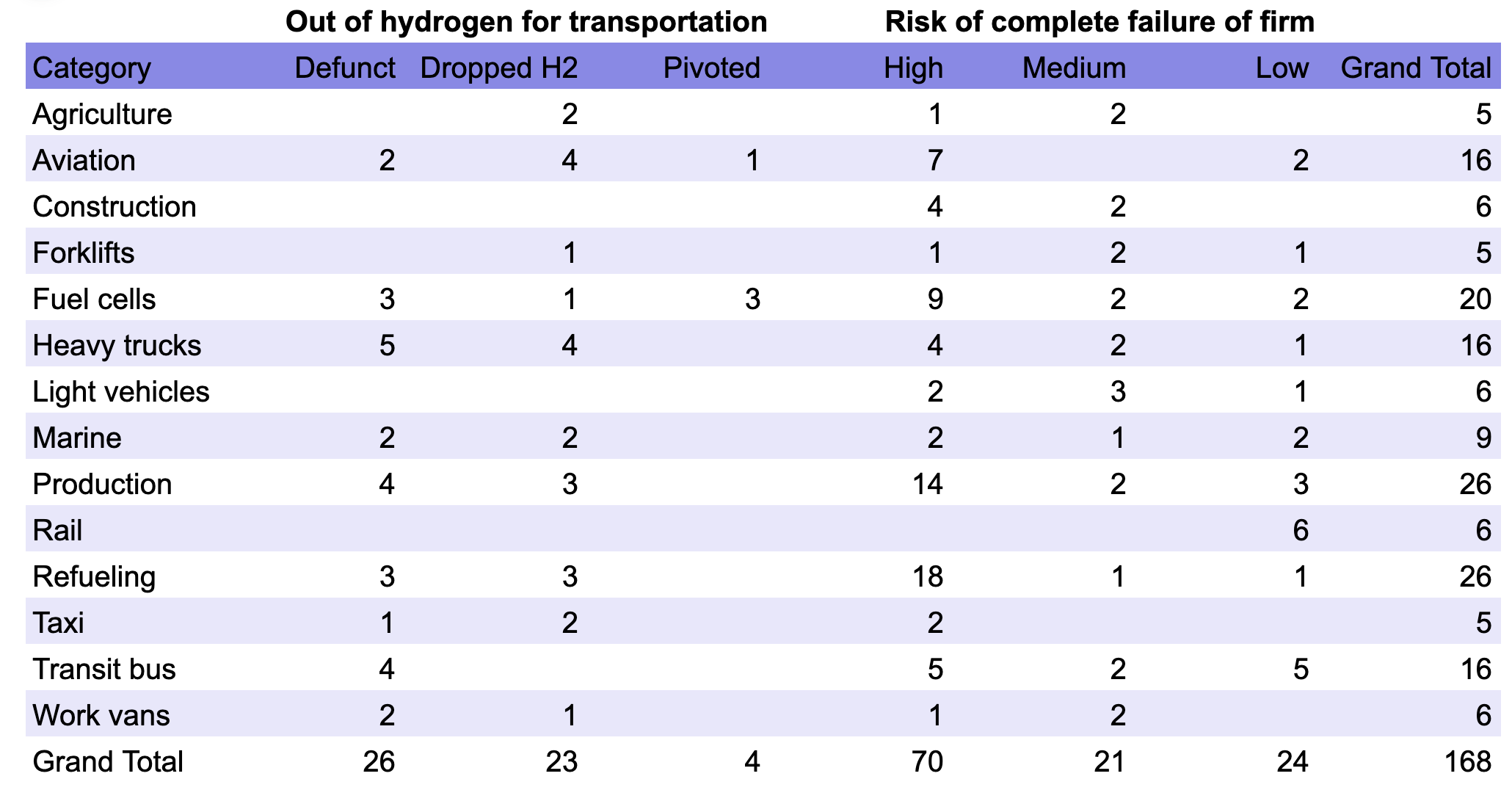

This year I have been maintaining a hydrogen transportation death watch, cataloguing companies that have failed or pivoted away from fuel-cell vehicles and the ones still limping along that haven’t declared failure yet. It’s a long list. Major automakers have wound down hydrogen car programs. Truck developers have declared bankruptcy or turned to battery platforms. Refuelling networks in Europe, North America, and China have shuttered sites. Station operators have written off investments.

Even in South Korea, the data point in one direction. Hydrogen passenger cars remain less than 0.2% of national vehicle sales. There is one hydrogen station for roughly every 170 vehicles, compared with one DC fast charger for every thousand electric cars. The infrastructure serves too few drivers to make sense on its own terms. Each additional station built deepens the financial loss, and every car sold locks in years of refuelling subsidies.

Hyundai’s hydrogen program has become an artifact of industrial policy rather than a business. The company’s battery-electric lines are its growth engines. Its fuel-cell vehicles exist to justify public investments, not because they make commercial sense. As electric cars expand globally and commercial hydrogen fleets contract, Korea’s network of hydrogen refuelling stations will become more isolated each year. The country has built the most complete hydrogen mobility laboratory in the world, but a laboratory is not a market. The data now emerging from that experiment suggest that hydrogen transportation is not failing everywhere except Korea. It is failing in Korea too, only more slowly.

Sign up for CleanTechnica’s Weekly Substack for Zach and Scott’s in-depth analyses and high level summaries, sign up for our daily newsletter, and follow us on Google News!

Have a tip for CleanTechnica? Want to advertise? Want to suggest a guest for our CleanTech Talk podcast? Contact us here.

Sign up for our daily newsletter for 15 new cleantech stories a day. Or sign up for our weekly one on top stories of the week if daily is too frequent.

CleanTechnica uses affiliate links. See our policy here.

CleanTechnica’s Comment Policy