Sign up for daily news updates from CleanTechnica on email. Or follow us on Google News!

One of the steady drum beats of various overlapping factions is “China bad.” Climate change deniers and delayers claim that it’s not worth doing anything because they falsely assert that China isn’t doing anything. In the USA and the UK, there’s a bipartisan demonization of China that means any negative stories get amplified.

China’s coal use gets pride of place in these narratives, especially in recent months. China permitted more coal plants in the past several years than the rest of the world combined, an average of two a week in 2022, per reports. Many people, reasonably, wrung their hands in concern, while others fueled Sinophobia or delay with the news. As always, it’s interesting to look underneath the surface of news like that to see what’s actually going on.

Let’s start with the Global Energy Monitor (GEM). What’s that?

“Global Energy Monitor studies the evolving international energy landscape, creating databases, reports, and interactive tools that enhance understanding. […]

“Our data tools are the products of global teamwork, with researchers, analysts, and volunteers from countries around the world each contributing their part.

“All data used in Global Energy Monitor’s work is attributed to an original source. These attributions enable users to identify where information is coming from, and to independently verify any information they may want to examine further. As our research efforts strive to follow the pace of global energy development, we remain committed to full accountability and transparency in our work.”

In other words, a global group of energy analysts ensuring that clear, well-sourced, and traceable data exists.

So what does GEM have to say about China and coal?

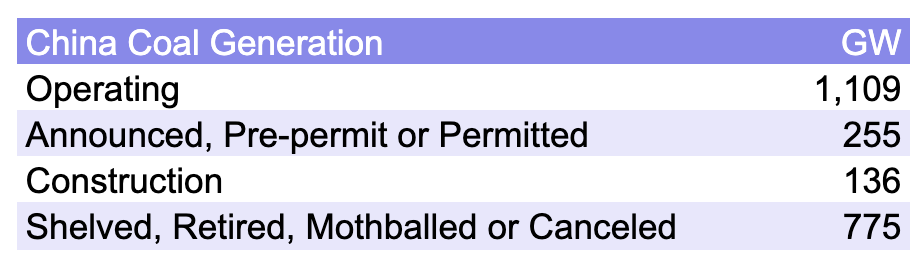

China Coal Generation Statistics from Global Energy Monitor, summarized by author

Is the 1,100 GW capacity of operating Chinese coal a big problem? Absolutely. Are the coal plants under construction a concern? Yes.

But narratives neglect to mention that 775 GW of coal generation that was operational and shut down, or didn’t make it to construction at all. Much of that shut-down older generation used the worst coal technologies which emit the most carbon dioxide per MWh, about 1.4 tons, while much of the operating and most of the in-construction coal generation is modern coal technology which emits about 0.8 tons per MWh.

Shelved and canceled coal generation plants that never reached construction are 652 GW by themselves, which dwarfs the 255 GW that are currently in pre-construction. The likelihood that much of the 255 GW of coal generation in the pre-construction pipeline doesn’t reach construction or operation is high, and the likelihood of operational and in-construction plants are mothballed or decommissioned entirely is high as well.

Still very problematic, and still needing to be shut down, but more nuanced, in other words.

And here’s the next thing. How does China operate its coal plants? On average, it uses them in much the same way that the west uses natural gas generation, as balancing power across the grid, providing electricity much more in peak demand periods than in lower periods. It’s not running them at peak capacity as ‘baseload’ generation.

For 2022, the capacity factor — the percentage of potential maximum electrical generation over a year that is actually generated — of Chinese coal plants was just 49%, compared to a little lower for the US coal fleet. That 49% is about the same as US gas plants. China is using its coal plants to keep the lights on in periods of high demand, in other words, and leaning on low-carbon electricity from its wind, solar, hydro, and nuclear generation as much as possible, just as other countries are.

China’s electricity system requires that low-carbon generation be used first, and coal last, contributing to challenges for operators to make any profits. That’s going to be adding a lot of pre-construction plants to those being shelved.

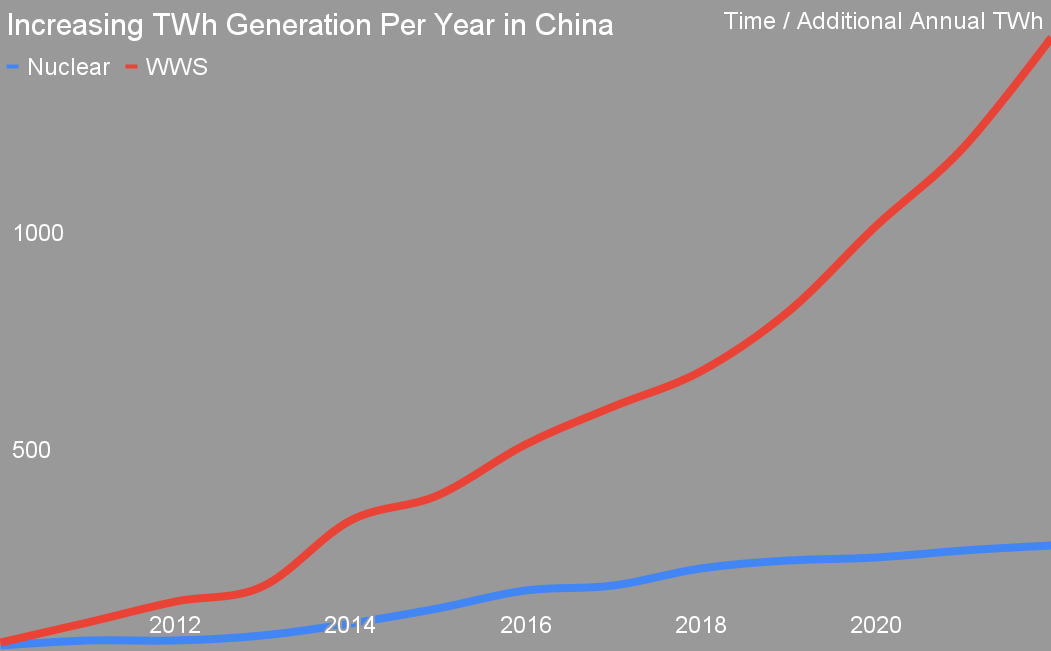

Increasing TWh Generation Per Year in China, chart by Michael Barnard, Chief Strategist, TFIE Strategy Inc.

And, of course, China is building vastly more low-carbon generation annually than any other geography in the world. Recent news indicates that this year is no different, with wind growing 15.1% year-over-year to reach 400 GW of capacity, and solar growing 45.3% year-over-year to reach about 520 GW of capacity, with more to come in the last couple of months. China’s 2030 renewables targets are expected to be met in 2025, years ahead of schedule, and then to keep rising. (It’s also worth noting that China’s nuclear program continues to flatline, with only one reactor attached to the grid in 2023 but still not in commercial operation as of this month’s World Nuclear Association update.)

China’s electricity demand is rising as well, given that the country is also electrifying its economy more rapidly than any other country, with over 1.1 million electric buses and trucks on its roads, two-thirds of the global market for electric light vehicles, electric subways and light rail in all of their cities, now 42,000 kilometers of high-speed electrified freight and passenger rail, and the launch of 700-container, 1,000 km route electric river ships.

But that’s the point. Electrified transportation, especially mass transportation, powered by a coal-heavy grid is still better than burning gasoline and diesel in terms of greenhouse gas emissions per passenger mile. It’s worth noting that Sinopec, China’s large national petroleum refiner and distributor, announced recently that China had reached peak gasoline this year.

Assessments by analysts who actually speak and read Mandarin, like David Fishman of the Asia-based Lantau Group strategy and economic consultancy, point to peak coal demand in 2024, a year ahead of China’s formal target. Why?

China’s massive infrastructure build-out has slowed, so cement demand has also plateaued. It’s a major consumer of coal outside of electrical generation.

“China’s cement production capacity has now plateaued at around 1,800 kilos per capita,” a Chinese Cement Association representative told the 2023 Coal Market Summit in early September in Nanning. “This is much higher than the production capacity levels of developed economies. We expect this number to drop long-term, following the slowing demand from the real estate sector.”

It’s expected that Chinese cement demand has entered a fairly sharp drop-off with 2.7% lower demand in 2023 and a full 61% drop by 2036. China’s economic outlook for 2023 is for a still enviable 5% growth, but that was downgraded recently from 5.5%. Petrochemical and aluminum industry coal demand is flat as well.

The net of this is that China is entering a new phase, one in which coal demand will be falling, electricity will be used vastly more for energy and that electricity will be generated by wind, water, and solar. At the same time, China will be tightening its carbon cap and trade program, something that’s going to give many of its firms a competitive edge in exporting to the EU, as the carbon payments in China will be credited on goods imported to Europe under the carbon border adjustment mechanism.

China may have permitted a couple of coal plants a week in 2022, but the underlying data shows that many won’t be built, the ones that are built are at serious risk of becoming stranded assets, and China’s coal demand growth is almost over. Its coal burning remains very high, but it’s not accelerating as the narrative suggests, and it will be declining sooner than expected.

Have a tip for CleanTechnica? Want to advertise? Want to suggest a guest for our CleanTech Talk podcast? Contact us here.

EV Obsession Daily!

I don’t like paywalls. You don’t like paywalls. Who likes paywalls? Here at CleanTechnica, we implemented a limited paywall for a while, but it always felt wrong — and it was always tough to decide what we should put behind there. In theory, your most exclusive and best content goes behind a paywall. But then fewer people read it!! So, we’ve decided to completely nix paywalls here at CleanTechnica. But…

Thank you!

Community Solar Benefits & Growth

CleanTechnica uses affiliate links. See our policy here.