Sign up for daily news updates from CleanTechnica on email. Or follow us on Google News!

For several years there have been a couple of parallel slow motion failures in the making, the use of hydrogen in transportation and the Jetsons’ fantasy of air taxis zipping over cities. Neither were based in economic, regulatory, or technical reality, preferring instead to have vast sums of governmental and investor money wasted because no technical or economic due diligence was undertaken by anyone who was listened to. As a result, I’ve started deathwatch lists for firms in both spaces.

In the case of hydrogen for transportation, it’s been clear for a long time that direct or battery electrification of all ground transportation would dominate, and now it’s just more clear as battery prices plummet, battery energy density increases, and global markets buy battery electric vehicles with rounding errors of hydrogen vehicles. For maritime shipping, it was clear that batteries, hybrids, and biofuel vessels would dominate, although it is somewhat unclear whether biomethanol or biodiesel will end up dominating.

For aviation, using hydrogen would require liquid hydrogen inside the fuselage behind passengers where it would flash freeze them before exploding in the case of a collision, not to mention throwing the ballasting of the aircraft off over the flight, leading directly to those crashes. Complete redesigns of all aspects of aviation would be required to build flying wings with sufficient human-hydrogen distance for potentially adequate safety, to rebuild airports to accommodate them, and to find some magical method of delivering absurd amounts of liquid hydrogen to airports.

All of the dreams of hydrogen for transportation, and indeed all hydrogen for energy plans, were based on the illusion that hydrogen would be cheap. That’s been obviously false for a very long time, with people like Dr. Joe Romm publishing technoeconomic analyses in his 2004 book The Hype About Hydrogen; and the founders of the Hydrogen Science Coalition, which includes engineers who worked with hydrogen professionally for decades publishing their assessments, and others like me doing assessments of specific proposals on multiple continents. To get cheap green hydrogen, both the electricity and the electrolyzers have to be effectively free and it has to be made at point of consumption because moving it costs so much. Reality doesn’t work that way, electrolyzers aren’t free, electrolyzers have proven to required firmed electricity, balance of plant continues to cost a lot, firmed electricity has proven to cost multiples of the assumed costs of curtailed electricity, and moving hydrogen around continues to be very expensive.

The past couple of years have made it clear that what was obvious from clear eyed technoeconomic analyses was true in the real world as well. BNEF has more than tripled its earlier estimates for the cost of green hydrogen in 2050. It now forecasts that the cost of green hydrogen will decrease from the current range of $3.74 to $11.70 per kilogram to between $1.60 and $5.09 per kilogram by 2050, a price range I still consider optimistic. This adjustment is primarily due to anticipated higher future costs for electrolyzers. That’s without moving the hydrogen around, which remains very expensive, and the low end of the range is only in China and India.

What’s also starting to intrude on the fantasy of hydrogen for transportation is the reality that it leaks and is a potent, if indirect, greenhouse gas. The most recent and robust assessment paper, “A multi-model assessment of the Global Warming Potential of hydrogen,” was published in 2023 in Nature and found 12–37 times the global warming potential of carbon dioxide at 100 and 20 years respectively. Meanwhile, multiple other studies and governmental reports have been published with empirical measurements of the smallest diatomic molecule’s strong tendency to leak. The evidence strongly suggests that it leaks 1%+ at every point in the supply chain, and as transportation fuel supply chains tend to be 7–8 steps, that leads to quite high leakage rates.

Right now 85%+ of hydrogen is used as an industrial feedstock at the point where it is manufactured, minimizing this problem. Although, it’s all made from natural gas and coal gas, so it’s not really something to write home about. But trucking it to bus depots, truck stops, and refueling stations would radically expand leakage. Putting small electrolyzers at points of consumption causes other problems, with the costs of manufacturing hydrogen shooting upward and small electrolyzers leaking more, per studies again.

And, of course, studies on hydrogen leakage from fuel cell vehicles find that they have a strong tendency to be leaking as well, with South Korea’s studies of its buses and fuel cell cars finding 15% of them were leaking.

It’s not like we haven’t known that there was a problem there. The impact on methane degradation was identified in 2000, and the first calculation of global warming potential published four years ago. That hydrogen leaks is like saying water is wet. It’s the smallest diatomic molecule in the universe and it has to be stored and transported at extremes of pressure or temperature that should make anyone near a refueling station or vehicle shudder. That seems to be taking a long time to reach policymakers’ ears, and major firms in the space are carefully ignoring it.

Then there’s the problem with reliability. Hydrogen refueling stations aren’t reliable. In Quebec, the refueling station was out of service for a full third of the hours of the four year hydrogen car trial the government ran. In California, during a six month period when the refueling stations should have been at their most reliable, they were out of service 2,000 more hours than they were pumping hydrogen, about 20% more. South Korea’s hydrogen refueling stations saw a cumulative 1,100 days of downtime between 2022 and 2023.

Then there’s the icing on the cake. Fuel cells aren’t reliable either. California’s bus maintenance data shows that maintaining their fuel cell buses costs 50% more than diesel buses and about double battery electric buses. The EU’s IMMORTAL program spent years and a lot of money tracking fuel cells and trying to engineer more robust ones, and managed to only get to a quarter of the targets, about 8,500 hours, about two years driving for a truck, before significant degradation set in. They couldn’t get membranes or catalysts to last in real world conditions with road going vehicles.

This has been masked in hydrogen cars because no one drives them very much. California hydrogen dispensing data vs the number of cars on the road makes it clear that they are driving them only 40% as much as normal cars. Quebec’s data saw governmental employees avoid driving the cars if they possibly could, with only 13% of the distance traveled per year as the average fleet vehicle in North America. A decent if misguided study on hydrogen rail in Spain I just reviewed was somewhat realistic about this, with under four years before fuel cell replacement, but the average I’ve observed for heavy duty cycle vehicles is two to three years, something that the industry just isn’t admitting. That’s why the EU’s annual status report found that bus manufacturers would only warranty fuel cell buses for 20 months.

And so, to the deathwatch.

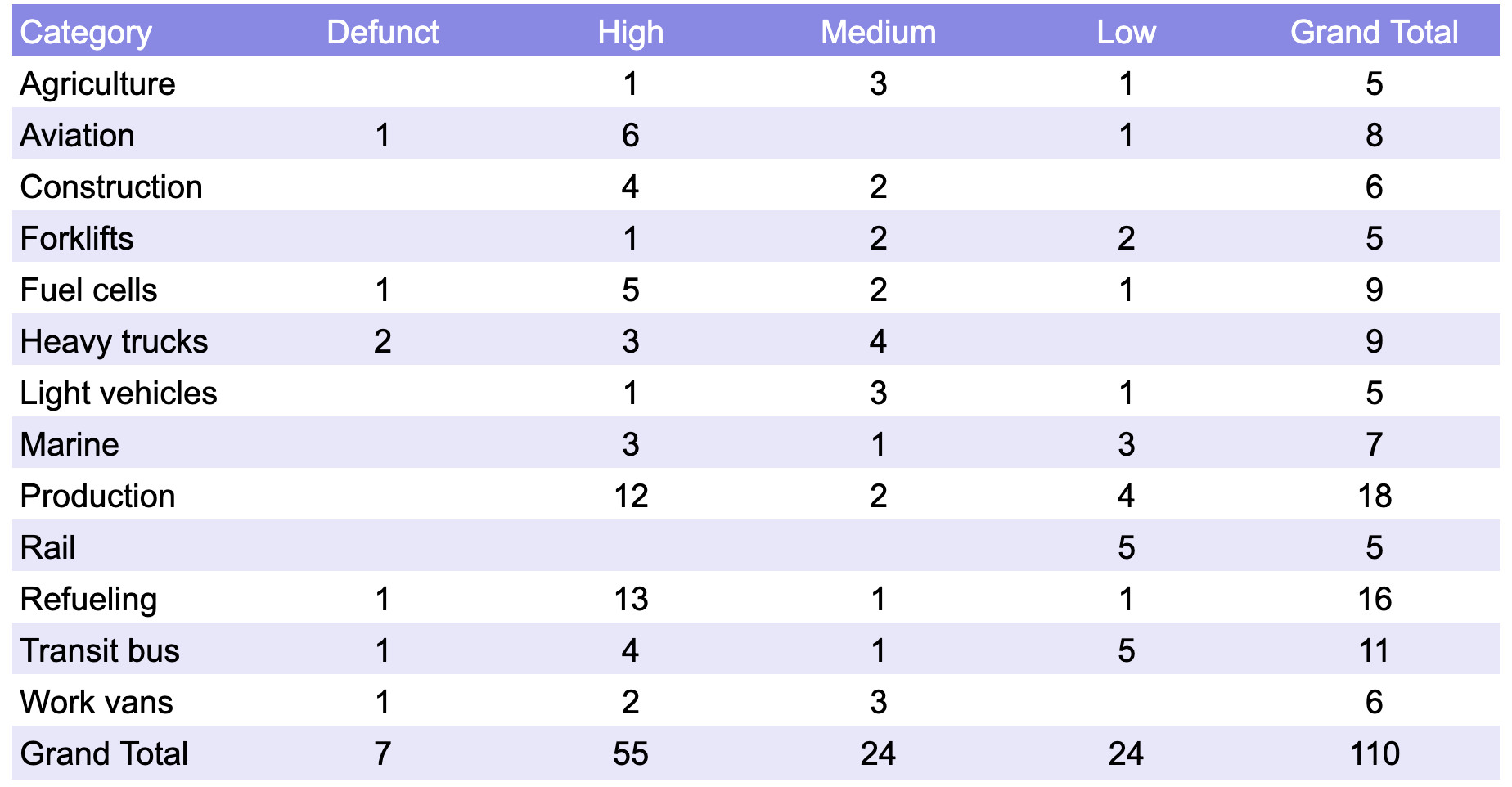

Seven of the 110 firms I’ve identified that are trying to push the square wheels of hydrogen into transportation have already gone under. Based on financials, another 55 are at risk of disappearing, with possibly most of them going this year. The ones assigned to lower risk categories are the ones that aren’t pure play hydrogen firms, but much larger firms that have hydrogen initiatives, so are less exposed. Many of those are in financial trouble of other sorts, so even some of the medium risk firms are likely to disappear, but all are likely to lose money in the space. Only the largest firms with the least exposure to hydrogen for transportation aren’t at risk of significant financial losses.

In the case of eVTOLs, the pitch decks were weightless confections pretending to massive serviceable obtainable markets and rotorcraft maintenance to flying hours ratios that were the inverse of every observed reality in the space. The proposals and pitches made it seem as if everyone would be hopping into a silent and clean air taxi on the corner and wafting gently over congestion. They made it seem as of the addressable market was orders of magnitude bigger than the entire current small aircraft market, never mind the much smaller rotorcraft market.

They made it seem as if cities were gagging for complex, folding, novel aircraft with rapidly spinning blades to fly over schoolyards and parks carrying commuters, and that thousands of commuters per hour could be serviced. They made it seem as if light air craft could fly at all hours of the day and night all year long, instead of being restricted to the calmest days, and likely to days with at best a dusting of snow or a sprinkling of rain. They ignored the 4-5 hours of maintenance per hour of flight time required for rotorcraft that beat the air into submission, pretending that they would have operating long days with minimal breaks between flights.

They ignored the realities of urban transportation that needs to move tens of thousands of citizens along major routes per hour, not dozens. They ignored the innumerable cities with rail lines from the city to airports. They ignored civil aviation certification requirements which experts I’ve discussed this with peg at about $1.5 billion per aircraft in the west, meaning exactly one entrant has raised sufficient funds that it might get to end of certification. Another firm, Vertical, is notable because the founders didn’t even realize certification would be required.

Of course, time passes and the FAA did a study last year of the reality of downwash and outwash from multiple much more rapidly spinning blades and found wind velocities that were into Category 2 hurricane ranges. None of the three tested eVTOLs had downwash and outwash velocities in the safe velocity range at the maximum measurement distance of 38.4 meters or 126 feet. As a result, the FAA released new rules for vertiports which meant that they had to massively expand their designed footprints, which massively increases their capital costs while simultaneously reducing their siting options. And the new rules severely restrict flightpaths as well, further limiting options. More burdens on already non-existent business cases.

The timelines of all of the firms are very aggressive, with many still saying that they’ll be flying this year, or next. Meanwhile, the FAA in a big meeting on the subject in January 2025 made it clear that they wouldn’t be certifying any eVTOLs until at least 2027. More impact on timelines. Joby will be 18 years old and have burned through over $2 billion of other people’s money by that time with nothing to show for it.

And so, to the deathwatch:

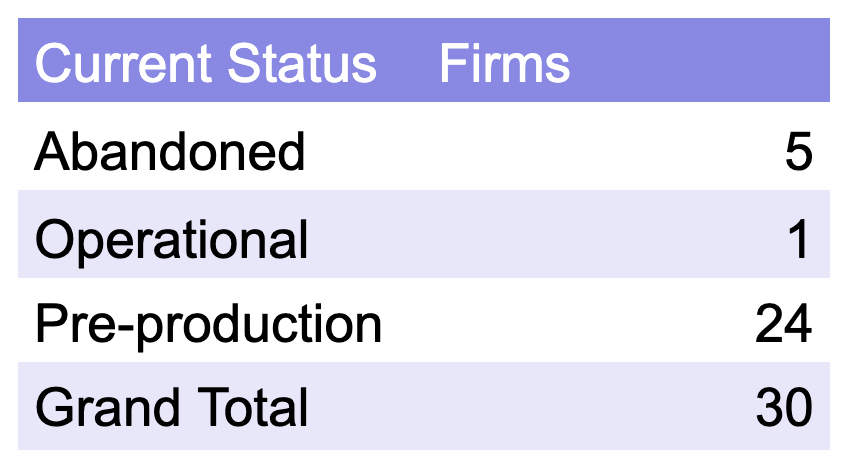

My current list has 30 firms on it, from giants like Airbus and Boeing to tiny startups. Five of the 30 players in the space I’ve identified have already abandoned the segment — Airbus and Rolls Royce — or out of business entirely — Lilium, Volocopter and Kitty Hawk (the last is in the Wisk joint venture with Boeing which is likely going to be abandoned this year as Airbus has left the building). I didn’t bother to assert risks for them as I did for the hydrogen plays because all but a couple are likely to be abandoned, and the ones that will persist are single person toys for rich people.

Only one has managed to be certified, eHang’s customer Cuisinart, and that only for flights over places where there are no people. It’s entering operations as a novelty Shanghai river sightseeing flight operator and trying to sell its knee capping quasi-autonomous device for $400,000 a pop. It’s the only one with a stock price that’s not grounded too.

While the creaky grandparent and best capitalized of the crowd, Joby, was founded in 2009 and is still years from being certified, the average age of entrants is seven years. After 16 years for Joby and seven for the average of the group, exactly one firm has anything operational that’s been certified and is being delivered. One of the flying ultralight person toy companies delivered a few to the US military several years ago, but neither Pivotal or Jetson have any confirmed deliveries of their current products.

Of the 24 pre-production eVTOLs, it’s unlikely any have sufficient capital to get through certification given that the two biggies, Archer and Joby, were SPACs and hence the Wall Street bros took big chunks of the raised capital in those pump and dump schemes.

As I’ve been publishing on the futility of hydrogen for approaching a decade and eVTOLs for four years, I’m going to be entertained this year as more and more of these firms leave this vale of tears. I’ll remain annoyed that all of that capital and all of those talented engineers and business people weren’t engaged in real solutions and moving the needle on climate change.

Chip in a few dollars a month to help support independent cleantech coverage that helps to accelerate the cleantech revolution!

Have a tip for CleanTechnica? Want to advertise? Want to suggest a guest for our CleanTech Talk podcast? Contact us here.

Sign up for our daily newsletter for 15 new cleantech stories a day. Or sign up for our weekly one if daily is too frequent.

CleanTechnica uses affiliate links. See our policy here.

CleanTechnica’s Comment Policy