Sign up for daily news updates from CleanTechnica on email. Or follow us on Google News!

Recently 21 municipalities in Poland sent a joint letter to the federal government begging for big subsidies for hydrogen for energy. Reports indicate that the cities that had already contracted for hydrogen buses hadn’t bothered to include realistic costs of hydrogen in their cost cases. The ones that have them are having trouble affording them or are running them on also expensive gray hydrogen. The ones that haven’t received them are very nervous about operating costs.

The letter included sample calculations of the costs that Chełm public transit will pay for hydrogen. The price of a kilogram of hydrogen is currently US$16.50, while the same amount of diesel oil costs $1.18. The difference in price over the year is as much as $655,000.

Of course, the letter makes the completely false claim that hydrogen is a climate change solution, rather than a large climate change problem.

Poland was already on my radar for buses because it’s home to Solaris, a large European bus manufacturer which is providing a lot of the hydrogen buses on the continent. It’s effectively the New Flyer of Europe, the bus manufacturer that’s made the wrong strategic choice and is likely to suffer considerable financial difficulties as a result. As I noted about New Flyer, for every hydrogen bus it sells, it likely loses three battery-electric bus sales to competitors like BYD. That’s because their battery-electric buses are more expensive and have lower specs because they are wasting time and money on very expensive hydrogen buses instead of optimizing their battery-electric buses, and hydrogen buses cost more to maintain and operate, leading to dissatisfied customers.

Solaris at least builds and sells electric buses. Polsat Plus Group, in collaboration with ZE PAK, a leading energy company in Poland, has developed a hydrogen bus as well, with ZE PAK of course absolutely needing hydrogen to be an energy carrier for it to have a future.

It’s worth tearing this apart to see what cities are going to be in what degree of financial trouble as a result of this.

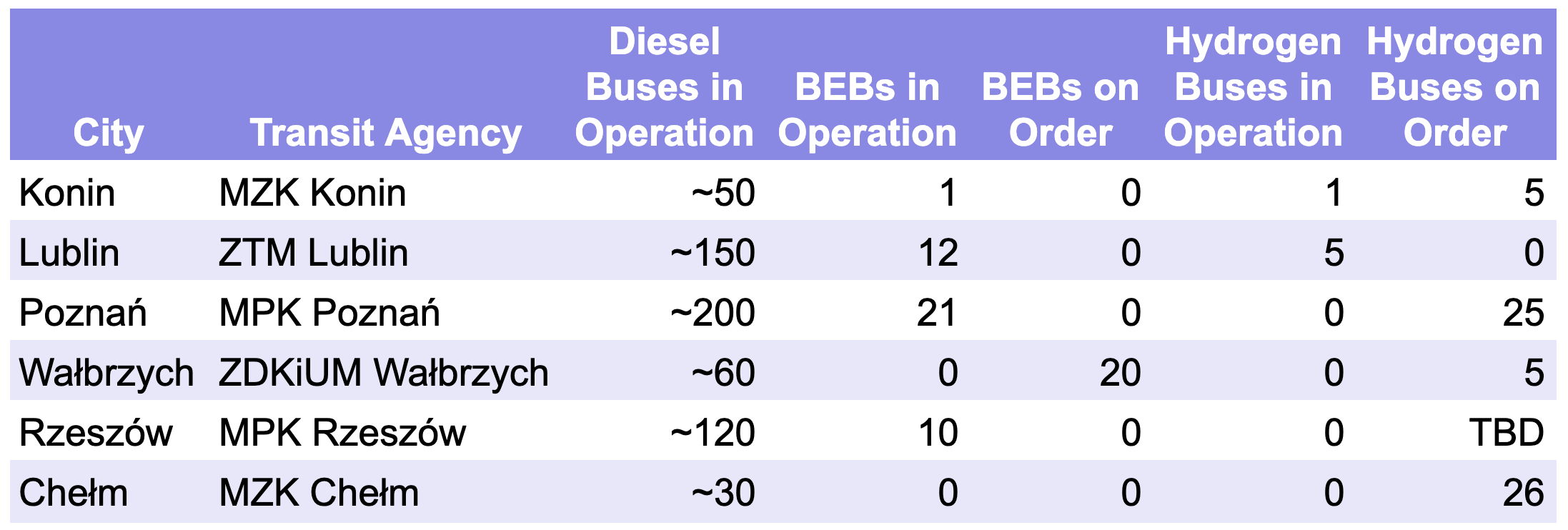

I pulled this data set together from public sources. Any errors are mine and the numbers should be considered accurate enough, but things may have changed since the public announcements. One thing that I’ve observed about hydrogen for energy announcements is that the announcements get brass bands and headlines and cancellations are rarely mentioned.

It appears that six cities have or are planning to have hydrogen buses in their fleets. Most of them appear to at least be planning to have more battery-electric buses than hydrogen buses, indicating that they are reserving hydrogen for where battery-electric buses currently have insufficient range.

As a note on transit strategy, that’s the wrong approach. Battery energy density is increasing annually while battery prices are decreasing rapidly. Electrifying shorter routes immediately and longer routes as bus prices drop while range increases is the right strategic choice. Betting against batteries in the 2020s is like betting against bandwidth in 2000, a bad call.

The sources of hydrogen are interesting. Konin gets its hydrogen from an electrolysis facility operated by Polsat Plus Group and ZE PAK, a 2.5 MW facility able to produce 1,000 kg of hydrogen a day, sufficient for 40 buses, although it’s only supplying one at present, and presumably six when the new buses arrive. One ton of hydrogen a day isn’t sufficient volume for any industrial process, so my assumption is that the electrolyzer is being run at very low capacity factors and hence very high costs for the hydrogen, hoping for demand to pick up.

While the facility sources renewable energy from nearby solar farms operated by ZE PAK, aligning with locality requirements, questions remain about its adherence to the criteria of temporality and additionality. Temporality hinges on whether the renewable energy used is generated simultaneously with hydrogen production, which has not been confirmed. Additionality, requiring the development of new renewable energy sources specifically for the project, also remains unclear without further evidence. These factors are critical in determining whether Konin’s hydrogen qualifies as fully green under international standards.

This really matters in Poland as its grid electricity remains among the highest emissions in Europe. It’s done a good job reducing that, but it has a long way to go. In 1990, coal was the dominant source of electricity generation in Poland, accounting for approximately 98% of the total energy mix. By 2023, this share had declined to around 60.5%. The reduction in coal’s share was primarily due to the increased adoption of renewable energy sources. In 2023, RES accounted for 27% of Poland’s electricity production.

That matters to additionality and temporality requirements, as marginal grid electricity is all coal. If the electrolyzer is running when the sun isn’t shining or it’s overcast, then coal plants will be providing the electricity. This is quite likely the case, as most hydrogen for energy plays are a lot dirtier upon close inspection.

Of course, the electrolyzer isn’t in the bus terminal but in the ZE PAK powerstation complex 14 kilometers from town. Hydrogen buses have to drive the 28 km round trip to refuel. Transit buses in urban environments generally travel 200–400 kilometers, so apparently in order to get the extra range buses, they have to drive 10% further for the fuel. That’s not exactly logical, but it’s par for the course for hydrogen transit schemes. And that is, once again, with very expensive hydrogen, so that 10% adds up to a big additional operational cost between the fuel and labor charges. It’s an hour of a driver’s time, after all.

Naturally these very expensive to operate and non-climate solutions are 90% funded by the Polish government.

It’s unclear where Lublin is getting the hydrogen for its five operating buses, but if it’s from the Konin plant, that’s 350 kilometers of driving for a diesel-powered hydrogen tube trailer one way, 700 kilometers for the return trip. Normal hydrogen tube trailers carry 300-600 kg of hydrogen. That’s about enough for the daily operations of five buses, so if true, that’s 700 kilometers of daily diesel truck distance for roughly 1,500 kilometers of bus travel. Not exactly a climate win, in fact even if hydrogen were really zero emissions in manufacturing, distribution would mean 50% of diesel bus emissions. That’s about 0.7 tons of CO2e per day.

Of course, hydrogen leaks and is a potent, if indirect, greenhouse gas. Peer reviewed and governmental studies are now making it clear that hydrogen leaks 1% or more at every transfer point. From electrolysis in Konin to pressurized storage tanks to the hydrogen tube trailer some mechanism for transferring the hydrogen into the five buses, it’s likely 10% of the hydrogen is leaking.

I say some mechanism because Lublin currently doesn’t have a hydrogen refueling facility. They’ve undoubtedly figured out what every transit agency does, that they are very expensive to build, so are hunting for the money. They don’t appear to have figure out that they fail constantly either. California’s public hydrogen refueling stations during the last six-month period for which this was reported in 2021 were out of service 2,000 more hours than they were pumping hydrogen. Quebec’s hydrogen refueling system, used by the now abandoned four year trial of hydrogen cars for governmental workers, was out of service for a full third of the hours of four years.

Returning to that 10% leakage rates. Calling it 400 kilograms of hydrogen delivered to buses, that’s 40 kilograms of hydrogen a day that doesn’t make it from electrolysis to powering wheels, but instead wafts into the atmosphere, where it interferes with methane’s degradation, prolonging that greenhouse gas’ 30-90 warming potential over 100 and 20 years respectively. That gives hydrogen a global warming potential of 13-37 times that of carbon dioxide, per the latest big study, published in Nature.

At 37 times, the 20-year warming potential, that’s 1.5 tons of CO2e a day, over 500 tons for the year. With the diesel emissions, that suggests 2.2 tons of CO2e per day, or well over the emissions of five diesel buses. Even at the 100 year level of 13 times CO2, the total emissions are in the range of 1.2 tons of CO2e per day, or about 85% of five diesel buses.

Of course, it could be worse. Poznań has partnered with PKN ORLEN, a leading Polish oil and energy company, to supply the necessary hydrogen fuel. Naturally, no electrolysis is involved. This is gray hydrogen made from natural gas, and they have a 15-year contract to deliver 1.8 million kilograms over that period. Naturally, it’s a 160 kilometer truck trip from the Orlen facility in Włocławek to Poznań. Once again, no climate benefits, and as delivery of hydrogen by truck is quite expensive, not cheap fuel.

It’s not in documents I was able to find, but it’s likely part of the 90% funding model from the Polish government.

At least Poznań is big enough and not committing its entire transit fleet to hydrogen so that the mistake, when it’s unwound, won’t fatally wound its finances. Chełm is apparently committing to hydrogen for everything. Naturally they’ve received around $24 million of Poland’s taxpayer money through the National Fund for Environmental Protection and Water Management to enable this bad decision. It’s not disclosed where they plan to get their hydrogen from, but if it’s ZE PAK’s Konin facility, that’s 1,000 kilometers round trip, and for 26 buses, that would be five hydrogen tube trucks powered by diesel every day covering 5,000 kilometers or so.

To round out the analysis, Wałbrzych is getting a brand new refueling station built by Orlen in 2025, according to the plans, so it will be receiving a tube truck a day of gray hydrogen with about 630 kilometer round trips from the Orlen facility. And because the hydrogen is transferred into the refueling station tanks before being pumped into buses, another exchange touch point, so likely a bit more leakage even without the inevitable compressor seal failures that purges a lot of hydrogen to the atmosphere. One hydrogen refueling station in California was seeing 35% losses and years of remediation only brought it down to 2% to 10% a year. Once again, no climate benefits.

Wałbrzych is likely getting 90% funding from the Polish government as well.

Rzeszów has partnered with Polenergia, which is planning to build a 5 MW facility 50 kilometers away. Of course, that’s an announcement, and right now announcements aren’t worth the pixels they are painted in. Of 221 million tons of announced hydrogen manufacturing, only 13 million have reached final investment decision per BNEF. Further, only 1.3 million tons of it has firm off-take agreements. The Polenergia hasn’t reached final investment decision yet, meaning it’s among the 94% of announcements and is very unlikely to reach construction and completion without a lot more governmental money. As a result, if Rzeszów does go ahead with its doomed hydrogen bus plans, it will likely be trucking in hydrogen with 760 or 840 kilometer round trips.

The Polish government provided about $17 million for Rzeszów’s hydrogen buses.

This is the context in which 21 Polish municipalities are begging for more national money for hydrogen. The Polish government is funding 90% of the capital costs of hydrogen buses. As a result, transit agencies are committing to hydrogen buses which will be much more expensive to fuel and maintain, and ones that won’t deliver any climate benefits. Sure, the air in towns will be cleaner, but that’s not what the purchasing is being based on. Polish citizens of those towns will end up with less reliable service because hydrogen buses and refueling systems fail a lot more than battery-electric equivalents or the diesel buses that they are supposed to be replacing.

Of course, tracing this back, the fingerprints of desperate fossil fuel companies are all over this. Polenergia was founded by Kulczyk Investments, which is the investment vehicle of the now deceased Jan Kulczyk, Poland’s richest businessman, and was very big in oil and gas. Now it’s trying to make hydrogen for energy a thing. Orlen, of course, is a Polish multinational oil, gas, and energy company. ZE PAK is a big coal generator that’s been trying to make hydrogen for energy a thing. The lobbying angles are obvious.

The Polish national government should shake loose from the lobbying and pay attention to the empirical evidence. Hydrogen is a climate change problem, not a climate change solution. It should stop funding hydrogen for energy schemes. It shouldn’t bridge the 93% fuel cost difference for hydrogen and focus on battery electrification, which is a climate solution. Of course, with all of those big, rich and influential players lobbying hard for a bad idea, the odds that Poland continues to waste time and money it are high.

Chip in a few dollars a month to help support independent cleantech coverage that helps to accelerate the cleantech revolution!

Have a tip for CleanTechnica? Want to advertise? Want to suggest a guest for our CleanTech Talk podcast? Contact us here.

Sign up for our daily newsletter for 15 new cleantech stories a day. Or sign up for our weekly one if daily is too frequent.

CleanTechnica uses affiliate links. See our policy here.

CleanTechnica’s Comment Policy